A couple decades ago I bought and sold cards at ThePit, one of the earliest sports card vault services. At the time it billed itself as the NASDAQ of cards and leaned heavily into the dot-com bubble that was engrossing financial markets and pop culture. New cards weren’t simply listed for sale, they introduced as an IPO. A ticker tape crawled across the screen listing recent transactions. I bought soooooo many Carlos Delgado Bowman rookies back then.

The site changed hands several times, first being acquired by Topps for almost $6 million in 2001. Topps never really figured out to make it profitable and sold at a loss five years later. After another five year ownership period the site shifted to its present setup.

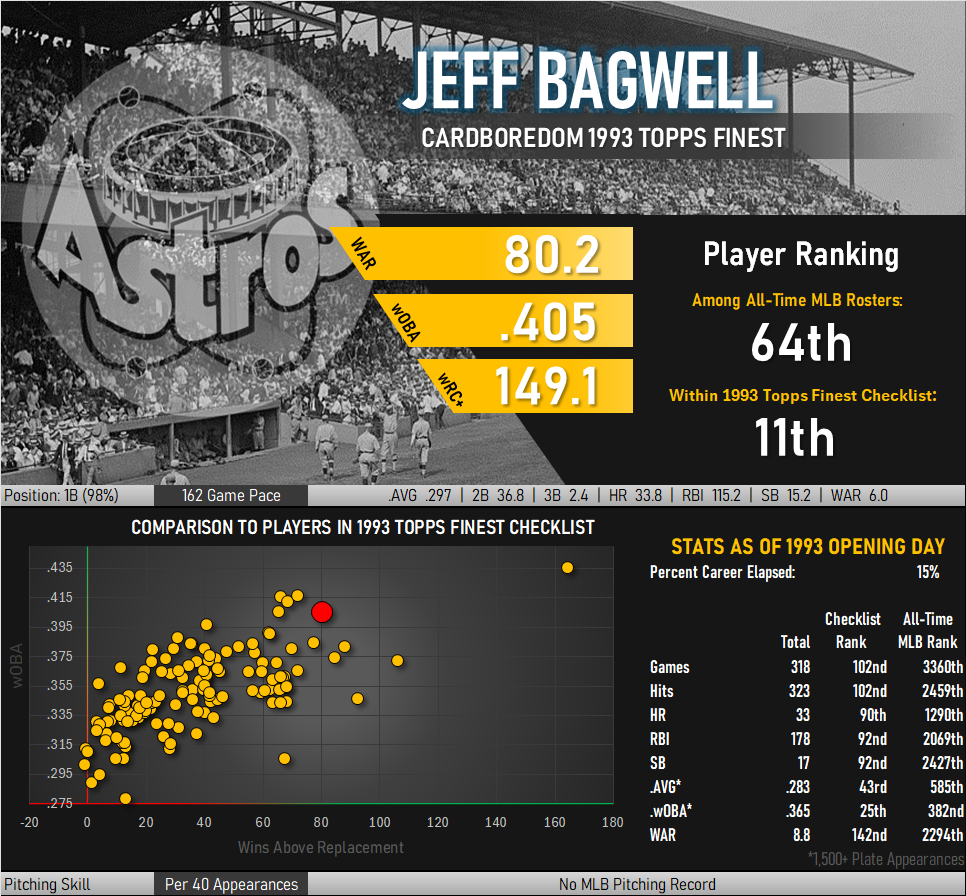

Checking out the site for the first time in many years I found a surprising number of 1993 refractors available. A pair of bigger cards from the set were added to my cart and quickly placed in the mail. The first of these features Jeff Bagwell on a card that has spent three decades among the top 10% of the checklist.

While shown in the midst of a batting follow through, the part of Bagwell’s swing that is most remembered is what happened before the bat left his shoulder. He looked like a real-life Starting Lineup figurine with an exaggerated stance. His feet were planted about as far apart as possible with a sharp bend in the knees, resulting in Bagwell looking like he was sitting down. This reduced the size of his strike zone and also made him more likely to be hit by pitches (three broken hands in three years).

At the time of this card’s release Bagwell was already considered a good player, though winning the 1991 NL Rookie of the Year Award may have elevated his reputation beyond what his stats indicated him capable of. He was shaping up the be a .290s hitter with 20 HR/90 RBI annual production, not quite on the same level of names like Frank Thomas. By the time Bagwell’s career wound down the pair would sport very similar career stats.

Bagwell and Thomas had similar approaches at the plate. Both were very selective in swinging at pitches and regularly drew 100+ walks in their prime seasons. High batting averages followed, with Bagwell topping out at .368 in 1994 and finishing his career within five points of Thomas. That 1994 season solidified Bagwell as the heart of the Houston batting order as he racked up a unanimous MVP award. Despite only playing in 110 games due to the players’ strike and a late season broken hand, his .368/39HR/116 RBI production would still have been enough to win the NL Triple Crown in 10 different live ball era seasons.

That was a unique season in more ways than one. Bagwell played at first base in all but one game of his career. On July 2 he took up right field (deep first base?) for 7 innings so the Astros could fit Sid Bream into the batting order. Bream had been batting .400 in the best streak of his career but hadn’t played in several weeks due to starters returning from injury. Bagwell, who himself would bat over .400 for the month, was shifted to make room. Bream went 0-3 (dropping to .368 in the process) and the experiment was quickly dropped.

That’s right: I have Bagwell as one of the best players of all time.

Back to 1B and the Frank Thomas Comparison

Bagwell’s career batting statistics closely mimic that of Thomas, but generally fall just short of his American League counterpart. At the plate, Bagwell was essentially 90% of Thomas.

However, their overall rankings as players are much closer when other aspects of the game are included. Thomas stole 32 bases over his entire career while Bagwell reached 30/30 club twice. Bagwell has more career stolen bases than noted speedsters Jackie Robinson, Mickey Mantle, Deion Sanders, and Jose Canseco. Many power hitters post gaudy RBI totals (Bagwell averaged 115 per 162 games), but this often comes at the expense of scoring runs themselves. Bagwell’s walks and baserunning helped him cross the plate 1,517 times, just a dozen times less than the number of runs he batted in. Frank Thomas’ differential is more than 300 runs.

Thomas also played about a third of his career as a designated hitter, a role unavailable to the lifetime National Leaguer Bagwell. Both exhibited negative lifetime fielding metrics, but Bagwell managed to carry a reputation for decent fielding for a good stretch of his career and won a Gold Glove in 1994. Bagwell’s defense is best described as “not bad” which is generally an improvement over what is expected for hard hitting sluggers working a corner infield position.