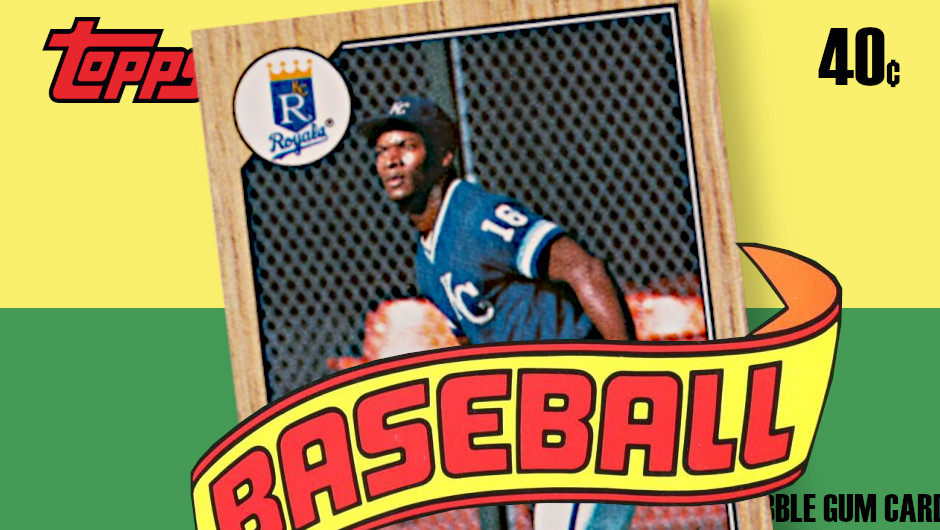

[Author’s note: Every year on my birthday I select a handful of instantly recognizable baseball cards to become “Wallet Cards.” The cards are always chosen with a theme in mind and are subsequently deposited for the next 12 months into my wallet. The cards are not encased in any sort of protective sleeve and quickly accumulate significant damage and wear. I document the before and after states of these cards and will sometimes keep a photographic journal of the adventures on which they have accompanied me. Each of these cards has its own story behind it, and at a later date I take them out and find out all I can about their history. This exploration of the 1987 Topps Bo Jackson baseball card is the latest in this series. Try this audio discussion from a pair of bots if you don’t want to spend time with so much text.]

Can we talk for a moment about our society’s historical fascination with woodgrain appliances? My family obtained our first microwave in 1990, a secondhand gift from the same grandmother that got me into card collecting by buying me a pack of penny sleeves. I have so many memories of this thing making bags of popcorn that had one completely burnt spot somewhere in the middle. The microwave was a Litton model (they also make warships!) and had a printed woodgrain design all over the exterior. Who would actually want a wooden microwave? In terms of user safety it seems…less than ideal.

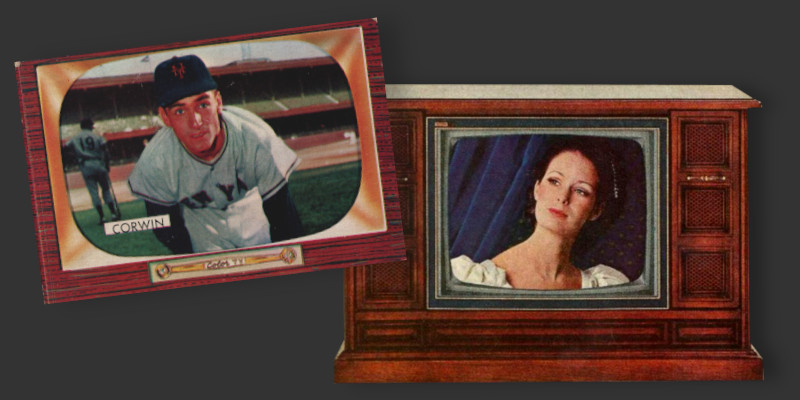

The microwave wasn’t the only faux-wood hand-me-down appliance in the early CardBoredom home. We had a woodgrain television with two giant dials that made “ka-chunk” sounds whenever they were turned. A few older family members had televisions with small screens set inside what appeared to be massive wooden frames, a look instantly recognizable to anyone with access to a 1955 Bowman baseball card.

Part of this desire to encase everything in wood was tied to the way in which new technology was introduced. Early automotive design, for example, wasn’t optimal for motorized travel. Instead, the first cars were iterative rather than transformative improvements over the familiar horse-drawn buggy. The first cars used existing horse carriages as their base, tillers instead of wheels, and even the term “horsepower” as a unit of performance measurement.

Purchasers of new technologies often needed a familiar frame of reference from which to draw conclusions about utility and product quality. I certainly listen for the artificial sound of a non-existent shutter when taking a picture with my phone. Televisions, like the ancient ones I grew up with, were sold by stores as an extension of living room furniture rather than an electronic appliance for the seamless delivery of advertising. “Real” furniture, in the eyes of a discerning consumer, was made of wood and not plastic or metal. The wood grain, even if only decorative, symbolized the long lasting nature of the item under consideration.

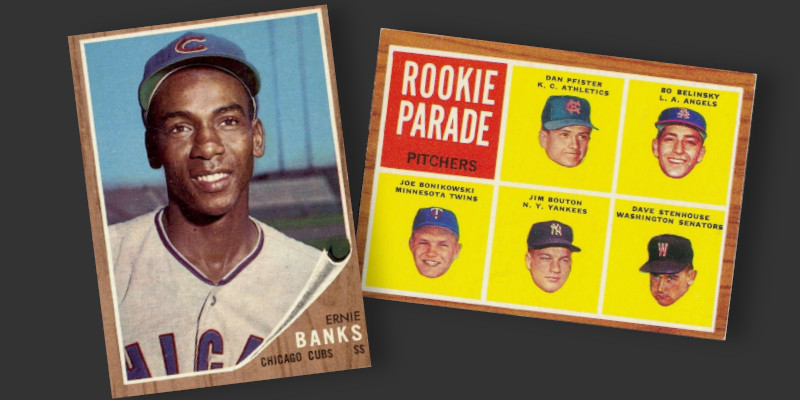

It was against this backdrop of wood paneled everything, including station wagons and the decor of the 1960s brick rancher in which I grew up, that Topps introduced its 1962 set. Having recently repulsed a resurgent Leaf Brands out of the market in 1960 and preparing to deliver send Fleer to the mat with a legal right hook the next year, Topps set out to instill a sense of permanence with the collecting public. What could be more long lasting than baseball cards seemingly carved from solid oak?

Fast forward a few decades and Topps, whose wooden ’62 cards looked as if they could be assembled into a Spanish galleon, is now fighting a multifront war against Donruss and a resurgent Fleer. New tech was broadening the cardboard conflict via a surprise attack from Sportsflics and the Topps legal reconnaissance unit could see the maker of lenticular cards preparing for a proper forward charge with its soon to be released Score brand. Having ceded the strategic high ground of the courtroom on antitrust concerns, Topps reached for perhaps its most potent weapon: Nostalgia.

The kids who had been buying cards and trying to get that autographed baseball back from the giant dog in 1962 were now adults. An economic boom was underway, oil prices had collapsed, massive tax cuts were newly in force, and these collectors were now professionally established with money to spend. In 1987 they were returning to their childhood hobby, piling in on top of the already sizable existing collector base. The product managers in the corporate office reached back into their archives/lumberyard for inspiration and produced what I consider one of the best card issues in decades: 1987 Topps.

Crap. I just lost the audience. If the backdrop of CardBoredom wasn’t so dark I would be able to see you getting up to leave.

Why You Hate ’87 Topps

Because they exist. In Quantity.

There are so many of these woodgrain cards. If you used a bulldozer to clear cut and burn as many of these overproduced cards as possible, some of the overflow would undoubtedly fall into the dirt and sprout anew into even more ’87 Topps. They are so numerous as to practically be a renewable resource.

Based on my reviews of Topps’ financial records and comparative analysis of the availability of key cards from benchmark sets, I keep coming up with estimates of 4.1-5.5 million of each of the 792 cards in the checklist. Future archaeologists excavating our landfills will undoubtedly demarcate 1987 by the line of pristine pink slabs of gum and numerous green and yellow wax wrappers. They’ll find it just a few feet below the shiny layer of America Online CDs marking the other boundary of the Junk Wax Era.

1987 was the year that brought Wall Street to theaters and Gordon Gekko’s red suspenders to the office. We even had an honest-to-goodness stock market crash during the World Series but managed to end the year with the Dow Jones Industrial Average showing a gain for the year. This was a period in which baseball cards moved from being a consumption good akin to checkout lane candy, being literally sold as packs of gum, to a durable good worthy of deliberate investment. Mentally, one needs permission to move from consumption to capital goods where the stakes are higher. You can’t responsible spend large sums on a card if you don’t have some background expectation of being able to recover those funds in the future. This necessitated the same kind of mental gymnastics that rendered short-lived electronics palatable by wrapping them in faux wood. Buyers needed to believe they were dropping these sums on heirloom quality wood furniture painstakenly crafted by the Amish in Lancaster County rather than the Topps printing presses in Duryea. If you ever paid more than buck for anything in this era, you probably carry some level of feeling cheated by these cards.

The checklist presents its own sources of discomfort. Collectors of an older generation want cards of Pete Rose, Jim Rice, and Mike Schmidt. All are present inside little woodgrain borders. Despite the fact that Schmidt appears on an All-Star card, all of these players were at the end of the careers and no longer playing at the same level they did in the minds of collectors who remembered pulling their rookie cards from packs. To them, these cards are the rectangular pine boxes in which we bury our legends. The rookie crop? The stats of one of the all-time best collections of flagship rookies became illegitimate in fans’ eyes in the aftermath of the steroid era. Bonds, McGwire, Palmeiro and a Canseco visually dreaming about his next contract signing became signs of rot rather than renewal in this forest of cardboard.

The overproduction compounds one last component of the creeping unease with the set. The cards are with certainty a calculated repackaging of nostalgia for the kids who grew up opening packs in 1962. Topps knew what they were doing. You knew what they were doing. And you hated that as a grown adult making grown up decisions affecting the real world you were going to fall for it and still love it. Despite near universal pointing and laughing, these same grown ups carefully sleeving and bindering pack fresh cards in 1987 would be the same ones signing up for wait lists to get “new” Beetles and PT Cruisers at their local car dealerships, both of which would eventually be available with optional wood grain paint.

These woodgrain cards were the last vestige of the era of wood paneled appliances, made when the ubiquitous white cubes that would become symbols of our technology replaced the electronics hidden inside faux-furniture shapes. The last brown microwave was probably made around this time. It was the passing of an era.

…and Why That Makes Them So Good

What is so redeeming about these cards? Because they exist. In Quantity.

So many people seem to hate these cards, but I would argue it is only because of their accessibility. They are omnipresent, and to those with a memory, the nostalgia is tinged with the bubble gum scented whiff of a collapsed Ponzi scheme.

We need basic, accessible cards like these. 1987 was so overproduced that it will be forever accessible to riffraff collectors like me (a former me? I’m feeling a little like the guy with a Deadhead sticker on a Cadillac). The cards are like a municipal park, a paradise in an ocean of concrete suburbia. They are ignored by thousands of people who struggle and work and claw and scratch and save to afford a slightly bigger backyard to “relax” in when just down the street sits hundreds of acres of walking trails, nature, volleyball nets, picnic tables, and scenic overlooks. 1987 Topps is where you take your 5 year old for their messy birthday party. Its the set you give a kid today who wants something different than the disappointing $30 blaster box at Walgreens while you’re trying to buy some embarrassing OTC products.

What if Babe Ruth’s rookie card was available in seemingly unlimited quantities for a dollar? 1987 Topps gives you all the Barry Bonds rookies you can handle want for that price. Why? Because it’s a bad card? No. Because you and everyone you know can have as many as they want. Cards like this are the definitive baseball cards, the ones that form the base from which collections grow. 1987 Topps, and sets like it, are the rainforest of the hobby. Without the oxygen they inject into our collecting lives we will all eventually asphyxiate alone in our individual, airtight collecting silos.

Not only are they attainable, they are fundamentally well executed cards.

Was Topps just repackaging and selling an earlier generation their youth one $0.40 wax pack at a time? Or had they improved a classic while opening the experience to everyone?

This was a 25th anniversary issue for Topps, the silver anniversary of the wood borders that last appeared just before the peaceful 1960s turned into the turbulent 1960s. The obvious wood borders were back for 1987, but they were done with the precision of a master carpenter. The color was uniform throughout the set, rather than their 1962 predecessor in which certain series looked like the local hardware store had run out of Topps’ preferred wood stain. Team logos, which had returned briefly in 1985 after their own 25 year absence, were back for 1987. Names were written in team color-matched text boxes in a font evocative of the comic books likely read by the target audience. Little flourishes, like the 45° cutouts on the corners behind the team logo and nameplate were tasteful callbacks to the gimmicky peeling poster motif employed in 1962.

Those corner embellishments started in the upper left, the first place to draw the viewer’s eye, and connected to the bottom right, a path that forced the observer to use the player’s image to complete the mental haiku formed by the action.

New York Mets. Fans roar as the dust clouds swirl – he is safe! Kevin Mitchell.

St. Louis Cardinals. Bubble gum pink jersey from Topps. Mike Laga.

Topps’ photography was much improved from the sea of posed shots of hatless guys with flattop haircuts captured on road trips to Yankee Stadium and the decaying Polo Grounds. Kevin Mitchell gives us one of the best looking cards of all time.

Even the crouching shots of catchers in foul territory that would be familiar to 1962 collectors get an upgrade. Lance Parrish gets that treatment, but does so in a white and navy Detroit Tigers uniform that works brilliantly with the card’s color palette. The stars at the bottom of his pants leg look almost like spurs while the low-velocity backdrop of 1962 is replaced by a pitcher giving it all he has in the distance. “This is the kind of speed that Parrish has to both catch and hit” – one subconsciously thinks – “before he goes jangling off to first base when after making contact.”

Even the uninspired subsets of 1962 had been refurbished for a new collecting audience. Managers are no longer relegated to a generic shot of a guy with “MGR” representing his position in small black text. The ’87s have “Manager” written in stark white script across the photo, making you feel like you won a prize rather than being tricked into added a manager card to your collection. There is even a bit of crossover between the two sets with 8 managers in the 1987 release appearing on 9 different cards in 1962 (Steve Boros gets into a multiplayer card in addition to his base card). The popular Turn Back the Clock subset, introduced the year before and showcasing previous Topps cards, shows up again in ’87 with an imaginary 1962 card of Maury Wills splashed across the front.

I have long thought most of Topps’ All-Star cards look worse than players’ base cards, but in 1987 they actually look better. The red and yellow player nameplate uses the same colors as their cobbled together 1962 brethren, and the only way those literal star-studded All-Star emblems can create the sensation of a Fourth of July barbeque is if they literally smelled like hamburgers sizzling on the grill.

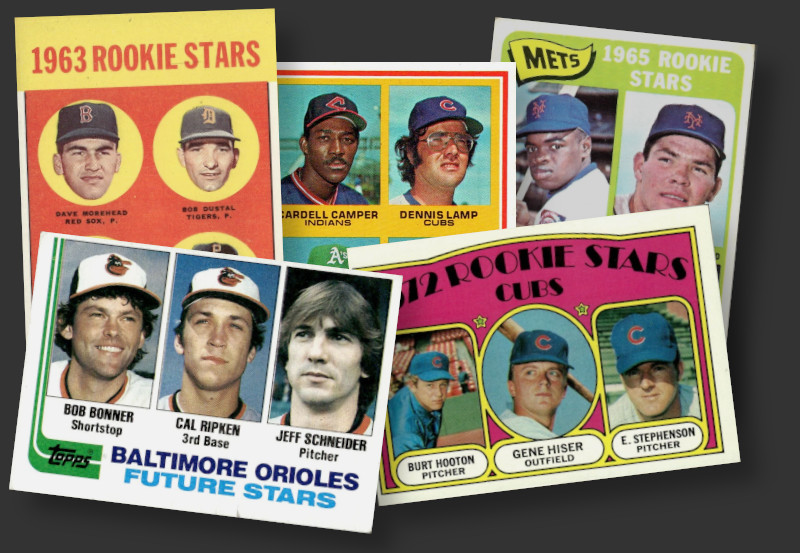

All of this, however, is just filler compared to the real improvement of the last 25 years. If collectors were in disagreement about the aesthetics of the 1962 edition, they are in near universal agreement about the visual quality of 8 particularly tough cards from the set: The multiplayer, floating-head-infused “Rookie Parade” subset that crammed 37 players onto 8 cards. Topps would continue the practice through 1982, eventually sidestepping the whole “what constitutes a rookie card” controversy in favor of replacing “Rookie Parade” and the subsequent “Rookie Stars” titles with the nondescript “Future Stars.” These cards were so bad, Topps literally created its yearend boxed Traded and Rookie sets as an apology to the hobby, giving collectors the single player rookie cards they had wanted in the first place.

The practice of making these ugly multiplayer cards ended in 1982 and, five years later when the faint odor of something off had dissipated, Topps brought back the Future Stars cards. This time they did it right, giving six Future Stars their own individual card, and one immediately stood out from the rest.

Bo Jackson May Have Been the Best of ’87 Topps

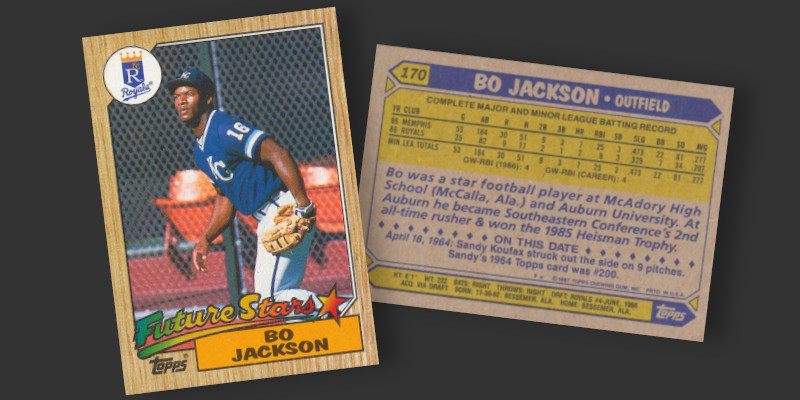

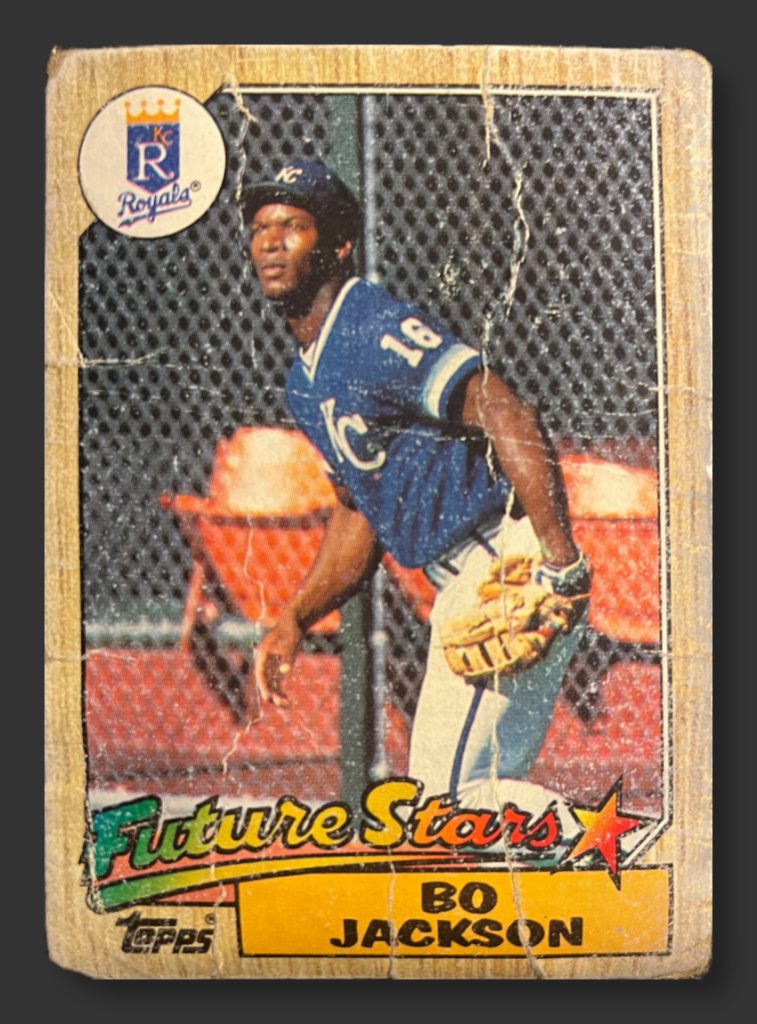

As card #170 in the ’87 Topps checklist, Bo was the first of the six players given the Future Stars treatment. Visually, the card is fantastic. Just look at it. The image shows an upward looking Jackson tracking a fly ball through left field, seemingly using superhuman powers to see the ball directly through the glare of the sun.

The selection of this particular image is interesting, as Topps had laid out its cards for 1987 in late 1986. He was drafted by Kansas City in June 1986, so Spring Training shots were not available. The red seats and chain link fence identify this scene as unfolding in front of the bullpen at Royals Stadium in Kansas City, and the deep blue jersey and empty bullpen imply the image was captured in a practice session. Jackson practiced at the ballpark for one week after his signing with the team, providing a brief opportunity for snapshots before departing for Double-A ball in Memphis. He returned to the Royals as a September callup, playing in 12 home games before the window shut on potential dates for this photo to have been taken. The timeframe for capturing Bo in action was rather compressed, and Topps was the only manufacturer of the big three to portray him in an action shot in their 1987 flagship card lineups.

The back of the card brings a bit of nostalgia for collectors of earlier generations. Most cards in the ’87 Topps set feature an “On This Date” fact that highlights various feats of baseball history. Notably, Topps ties in its own long running association with covering the game by mentioning a bit of baseball trivia and then identifying the specific Topps baseball card issued concurrently with that moment in time. The Bo Jackson card references Sandy Koufax recording an immaculate inning in 1964 before directing collectors to seek out Koufax’s card #200 in the ’64 Topps set.

Bo Knows Trade Night

What do you do with millions upon millions of Junk Wax cards? You trade them.

Now, you can’t just trick your friend’s little brother into trading away a Bo Jackson rookie for a Mario Mendoza just because the latter card is older. There has to be at least a veneer of fairness in your shark-like eyes as you strategize a potential trade offer.

That’s where your trusty monthly price guide comes in. In the era of Bo Jackson, anyone trading in my friend group had to abide by one rule: Each party in a transaction had to receive equal trade value from the same price guide. If you gave up a $1 card, you had to receive another $1 card or some combination of lesser value cardboard that had a cumulative value of a buck. There was no arguing with that logic. It had come down to us from on high from Jim Beckett. We had to follow what he told us. He was a doctor, after all. Besides, any inaccuracies in the price guide were there to be used in your favor. Of course you were going to agree with whatever the guidebook said…you were the one using those numbers to your advantage in building your collection.

What follows are groupings of various cards carried in yearend price guides at exactly the same value. The reported price represents the average value of the cards high (retail card shop) and low (discount card show) prices. While we may have had differing opinions about which card was best in any of these comparisons, an exchange of cardboard in any direction would have been seen as completely fair by the local playground vigilante committee overseeing enforcement of the price guide rule.

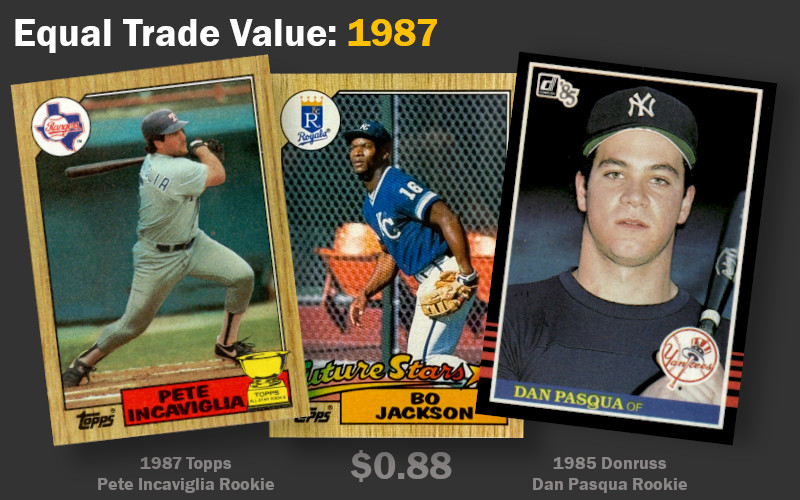

Trading rookie cards is a bit like making a bet. “I think Player A is the next generation defining talent,” you say to your friend who is shaking his head in disgust at your limited grasp on the finer points of baseball. “No,” he says with a patronizing hint in his voice, “Player B is the one who is going to set all the records.” Neither athlete had played more than a couple weeks with their respective big league clubs. How do you settle this argument? You make a bet in the form of exchanging cardboard.

| PLAYER | HR | RBI | .AVG | wRC+ | WAR | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Player A | 30 | 82 | .250 | 108 | 0.6 | Reigning Top NCAA Player |

| Player B | 2 | 9 | .207 | 69 | -0.7 | Might quit MLB – was just selected again in the NFL draft |

| Player C | 16 | 45 | .293 | 153 | 2.7 | Plays in a Yankees lineup with Rickey, Winfield, and Mattingly |

This is the set of facts on the ground at the end of 1987 when packs of wood-grained Topps card disappeared from store shelves, forcing you to seek new cards from rival collections. Which outfielder were you staking your prospecting reputation on?

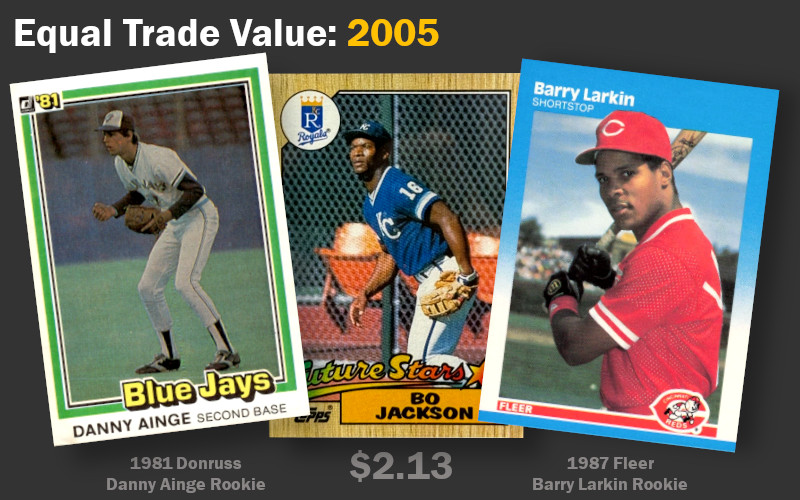

Bo Jackson was seen as a novelty within the hobby, not a potential superstar. His college baseball stats had question marks. There were serious questions about his ability to hit top level pitching and he had just been selected in the NFL draft by a team on which he was on good terms. Any potential increase in interest in his rookie was seen as being more akin to the curious baseball rookie cards of NBA Hall of Famer Danny Ainge rather than his baseball skills. Put simply: In 1987 this was seen as a card for football fans who wanted a momento of what was almost certainly an intriguing, if brief, diversion into baseball.

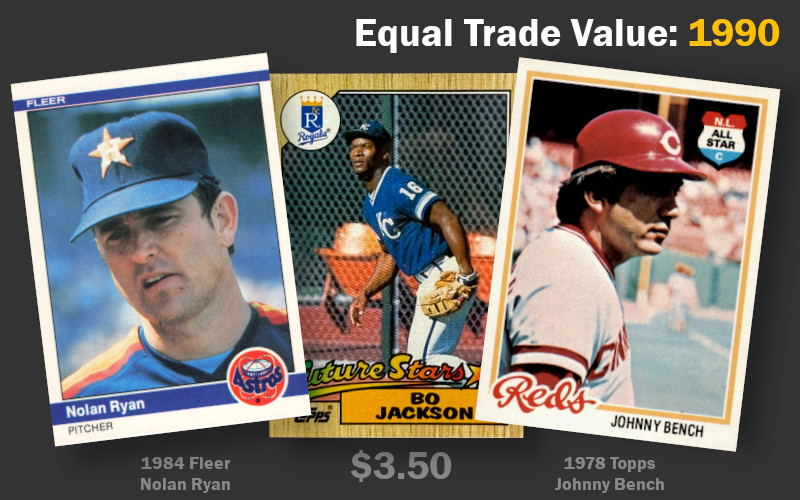

Bo was coming off the best year of his career in 1990. He was the face of Nike alongside Michael Jordan and had his own cartoon series. He had overcome that early curiosity label and his rookie card was considered legal tender exchangeable on demand for cards of established legends like Nolan Ryan and Johnny Bench. They were on their way to Cooperstown and it wasn’t hard to imagine the Royals outfielder joining them if he continued to improve. Getting an ’87 Jackson card would require not only parting with a card of a top tier player, it would require parting with one of their cards from a good set.

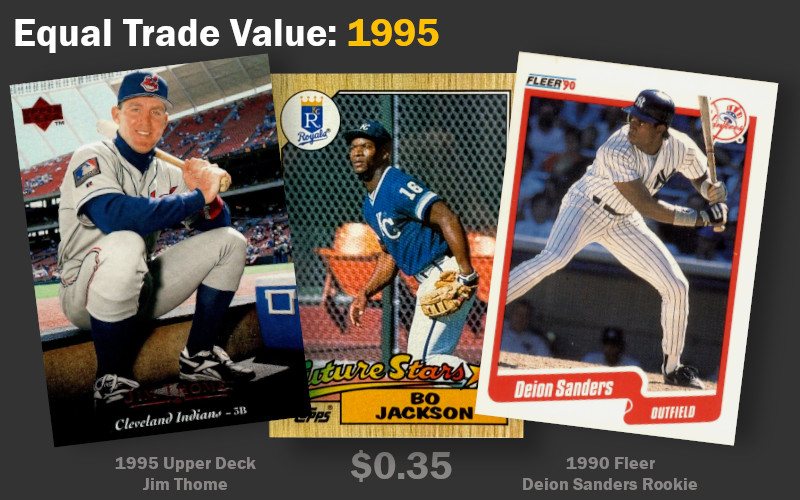

While five years later the Jackson rookie was still a star card worthy of attention, it was traded for stars of a lower tier. A current year Upper Deck Jim Thome might be of interest in a one for one swap. A collector wanting to keep the multisport rookie theme going could be persuaded to give up a mass produced Deion Sanders rookie as well. Good trades could still happen, they just wouldn’t be the talk of the playground. Bo retired in 1995.

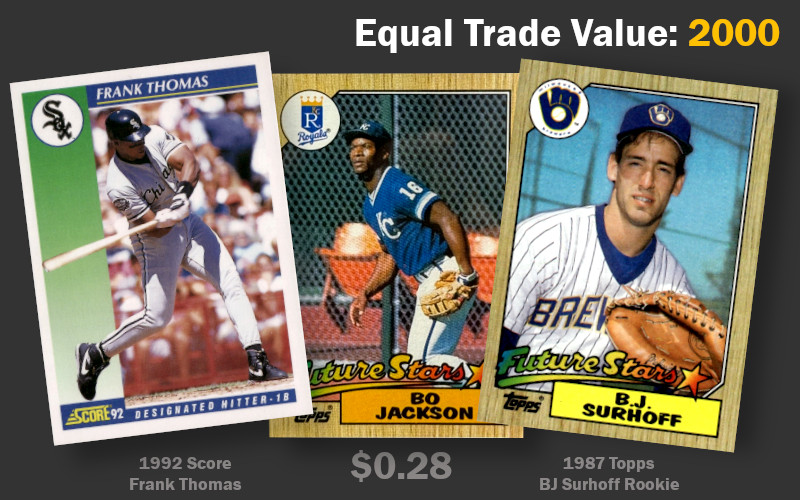

At the turn of the millennium the Jackson card had fallen into that generic “good but overproduced” label that subsumed so many others like it. Quarter boxes of the era were overflowing with just about any non-rookie base card of Frank Thomas, cards that anyone opening a pack back then would have been ecstatic to pull. Fellow ’87 Topps Future Stars BJ Surhoff, by now a solid component of the Hall of Pretty Good, found his rookie card changing hands on equal footing with Bo. Note how Topps didn’t just use generic colors to represent each team, they actually matched the hues in the color block to the specific amber and yellow of the Kansas City and Milwaukee logos.

Remember that Danny Ainge reference that was top of mind for collectors in 1987? A generation later the cards had come full circle and were seen as entirely interchangeable. Bo’s career had indeed been ended by his desire to play football, but through injury rather than attrition towards his better sport. His Topps rookie likewise fell in line with the big injury rookie of the era, Eric Davis’ 1985 Donruss card. This was still an improvement in collector demand compared to just a few years earlier. It was, after all, on par with rookie cards of Cooperstown-level talents like Barry Larkin and Jason Giambi.

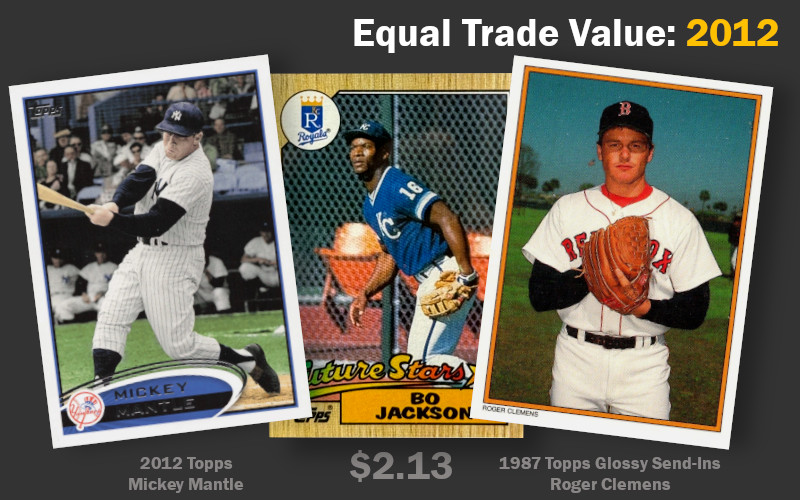

Sometime around 2012 was the last time anyone took a printed price guide seriously. Outside of the most liquid cards, the inputs just weren’t coming in with the regularity needed to keep pricing data fresh. The Future Stars Jackson continued to appear with a trade value hovering just above $2, a novelty literally on par with a $2 bill. This period had no shortage of cards that would raise an eyebrow just like one of those Thomas Jefferson bills being pulled from a collector’s wallet, and all were available at that same price point. Topps was reloading its nostalgia gun, putting Mickey Mantle into that year’s regular base set. Collectors who already had one of the five million or so Jackson rookies were discovering the joys of mail-in offers associated with the set. Cards from the Glossy Send-Ins issue of top players like Roger Clemens were suddenly in demand, rising from quarter boxes to stand alongside the more established woodgrain Jackson.

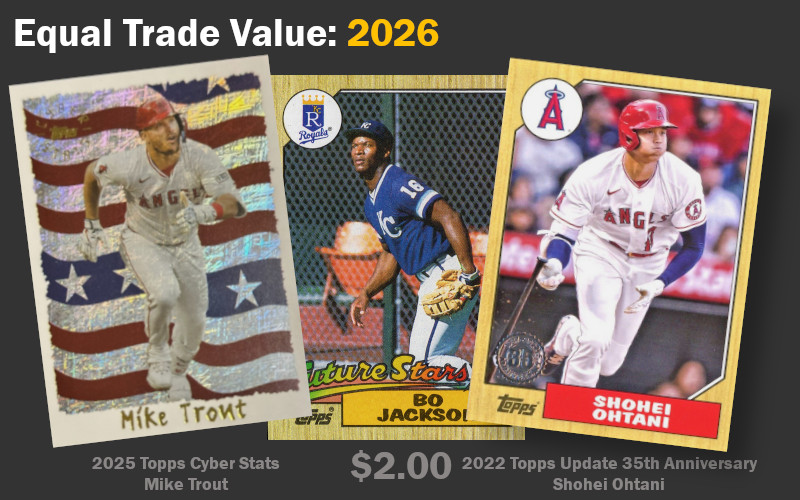

Apparently the current price for middle age nostalgia is two bucks. The biggest names in the hobby are now being pasted onto modern recreations of the designs of the Junk Wax Era. Mike Trout, seemingly battling his own health issues, has a 1995-inspired Cyber Stats insert in last year’s Topps issue that just might tempt someone with an extra Bo Jackson rookie lying around. Similarly, Shohei Ohtani has cardboard available in that familiar 1987 wood grain with Topps’ 2022 35th Anniversary reprisal of the design. To quote The Blues Brothers, another bit of ’80s nostalgia, “That’s a lot of entertainment…for two dollars.”

A Wooden Wallet Card

New York City is home to more than 120 billionaires, with many more out of town members of the four comma club owning secondary residences in the vicinity. The concentration of the uber-wealthy is so high alongside the southern end of Central Park that the area has garnered the nickname “Billionaires’ Row.” Despite cooperative boards guarded by dragons and an army of well-appointed uniformed doormen, anyone can play a game of catch in the only patch of green grass visible from their floor to ceiling windows. The park belongs to the city, forever accessible to anyone that needs to just get out of the house and enjoy the sunshine.

1987 Topps fits that same role in a hobby increasingly designed around buying lottery tickets packs in hopes of landing the next 1/1 logoman insert or curating some Gem Mint 10 condition rarity. No matter how financially imposing collecting baseball cards become, we can all contemplate a pack or two of ’87 Topps. After all, there’s enough to go around.

I kept a 1987 Bo Jackson card in my wallet for a full year, and the full effect of time and long car rides can be seen in the creases that accrued on the face of the card. Consider taking your own ’87 Topps cards to the park to play.

I am what demographers refer to as a “geriatric millennial.” (**pushes ironic wide frame glasses up** “I was irrelevant before it was cool.”) I have no doubt that someone has already put together a dossier affixed with that label and designed a marketing plan designed to send me rushing to their online shopping cart in a fit of nostalgia. Twenty years from now we’ll see waves of the equivalent of faux-woodgrain Fanatics products aimed at the next generation.

I bet we haven’t seen the last Taco-Fractor.