I just came back from a brief trip. Having traveled 5,108 miles in the past 48 hours to see a rock band, I spent some of my time in the air contemplating how impossible this schedule would have been just a few generations ago. The journey home provided another reminder of the endurance needed for long distance travel a century earlier.

One option would have been a very tiring cross country trek in a Ford Model T, which would continue to come off the assembly line for another 2 years. The now-familiar numbered routes came out of a 1925 Joint Board on Interstate Highways effort to create a practical classification system that would simply driving directions. This replaced a chaotic series of ever changing road identities maintained by competing private auto trail associations that provided motorists with maps and guides.

The JBIH designated the stretch of road , shown above, from Springfield, Missouri to Newport News, Virginia as Route 60. The route was later expanded to incorporate the Midland Trail, creating an unbroken link between the East Coast and Los Angeles. While it never passed through Las Vegas, this bit of cross country asphalt does come within five miles of my home and directly connects me with the parking lot of the Richmond airport.

One of the signs I routinely pass on this road bears “TOE INK WAYSIDE” in white Highway Gothic letters across a blue background. The area to which the sign refers consists of a small parking lot, a handful of picnic tables, a few historical markers, and an area for trash and recycling to be put away. It is the exact spot shown in the photo above.

Waysides were one of the earliest bits of infrastructure to be built in response to the emerging road networks. By 1925 there were already hundreds of these roadside facilities across the country, providing tired motorists with places to eat and rest. Some were privately maintained, others were created as cooperative endeavors to make small towns more appealing to those passing through. Some went as far as to staff information booths and provide security for those wishing to camp overnight. Favorable mentions of a wayside in travel guides could lead motorists to select one route over another, generating competition to provide ever increasing amenities for travelers.

Out of these efforts and the building of the Interstate Highway System came the rest stops so familiar to today’s travelers. Older waysides have largely been replaced by the newer facilities or retired in favor of now ubiquitous service stations and fast food restaurants. One of the last waysides to be built, Toe Ink was constructed in 1951 and remains one of 18 still in service across Virginia.

The 5,398 Mile Commute to Work

One of the differences between my trip and that of someone traveling in the era of Bob Hope “Road to..” comedies is the level of communication with those at home. I was able to text family, check e-mail, get real time flight information, and monitor the status of reservations awaiting my arrival. Had there been a change of plans, such as a canceled concert or family emergency, I could quickly correct course.

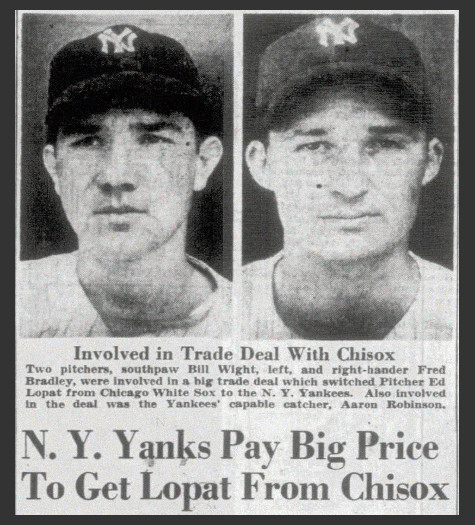

Instant communication would have been welcome for a specific New York Yankees pitcher in 1948. Lefthander Bill Wight was one of a trio of New York players traded to the Chicago White Sox in exchange for Eddie Lopat. Lopat, who lived in barely outside of New York City limits in Hillside, New Jersey, got in gear and headed to Yankees camp in St. Petersburg, Florida. So did Wight, who needed to depart earlier than his teammates to make up for the fact that he would be traveling from his home in Healdsburg, California.

This presented a problem given the timing of the trade. Because Wight left so early for a cross-country commute, he was not present to receive news of the trade at his residence. Further complicating the matter was the fact that the White Sox were conducting Spring Training in Pasadena, California. Instead of traveling 443 miles south, Wight was obliviously intent on finding his way 3,000 miles east.

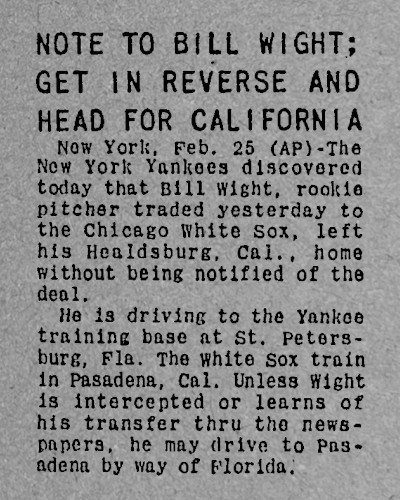

The usual ways of contacting someone had their limits with such a road trip. Wight’s phone was going unanswered in California. He wasn’t making outbound calls along his route as he was unaware of any party needing a call from the road. Telegrams were still a method for contacting traded players, but unless someone wanted Western Union to roadblock every southern highway this would be ineffective. The only hope to reach him was to get word of the change of plans into newspapers and hope he did some reading along the way.

A notice was quickly dispatched across the country via the Associated Press’ newswire. Within 24 hours the notice shown here was being reprinted in sports sections across the country.

It turns out Wight didn’t do much reading behind the wheel. When asked at a Clearwater gas station what was bringing his California-tagged car to Florida, he responded that he was on his to the Yankees training camp. Less than an hour from his destination he was informed that he needed to rocket more than 2,500 miles in the opposite direction.

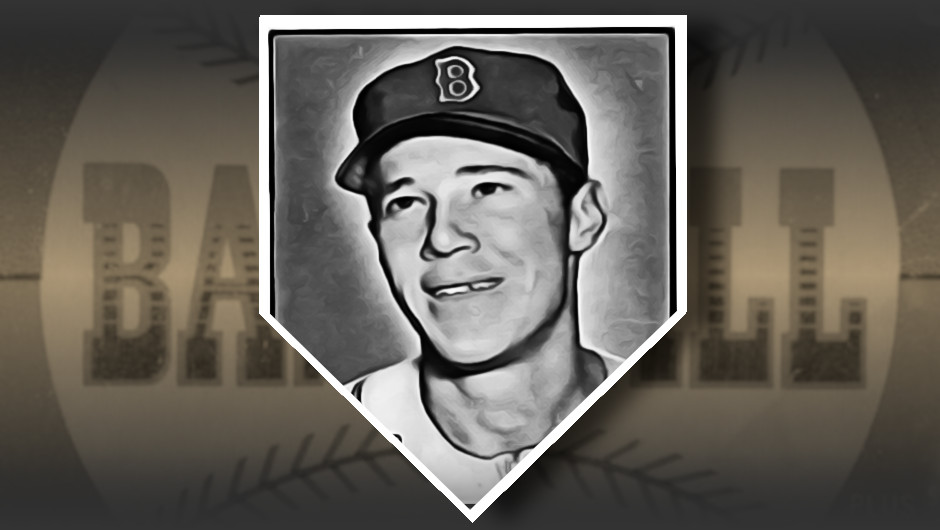

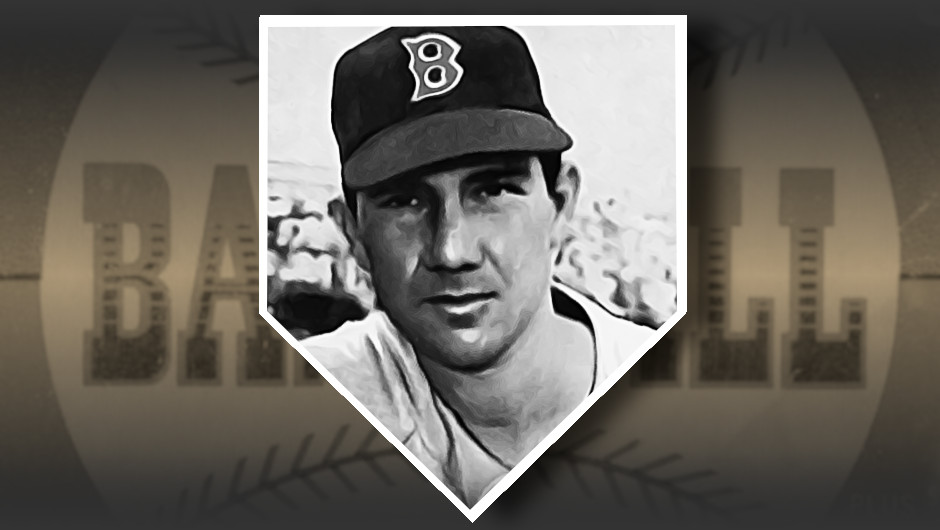

Wight eventually made it to the ChiSox’s west coast camp, taking a roundabout 5,398 mile path that brought him into contact with Route 60 in Arizona and Southern California. He pitched three seasons with Chicago, going 34-49 with a 3.88 ERA. Possibly learning from Wight’s 1948 inadvertent road trip, Chicago made sure to trade him to the Red Sox three months before the opening of 1951 Spring Training.

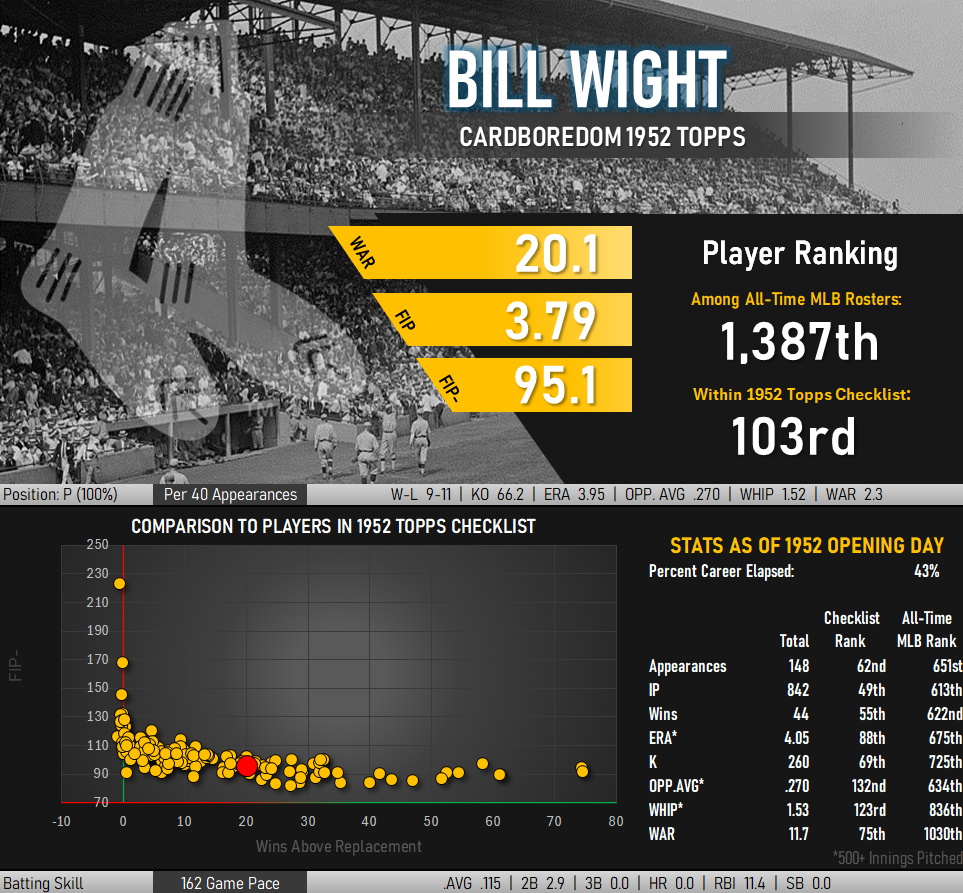

Getting traded turned into a bit of a habit with the now well-traveled southpaw. He would stick with the Red Sox for a year and a half, then move to Detroit, Cleveland, Baltimore, Cincinnati, and St. Louis, all within 10 years of that NYY-CWS swap. He posted a 77-99 record with opposing teams batting .270 against him, numbers that seem to match with being traded so often. However, supplemental metrics like adjusted FIP reveal a pitcher who was a touch better than the headline numbers would indicate.

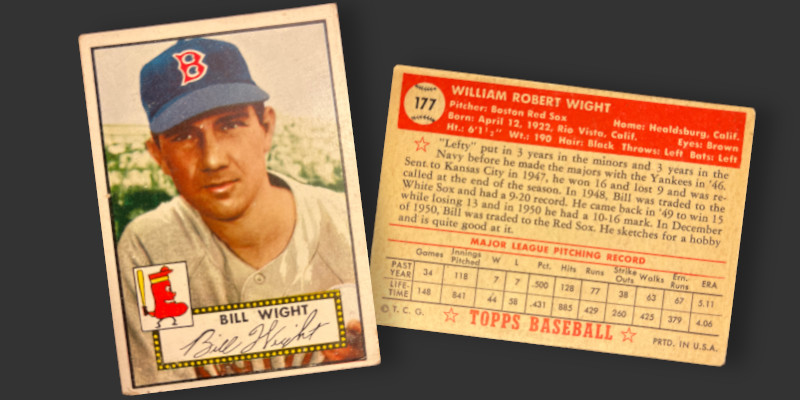

This ever-accelerating rotation of hats worn by Bill Wight had him starting the 1952 season with Boston. I’m not completely sold on the idea that we’re actually looking at a genuine Red Sox cap on that year’s Topps baseball card, as that logo looks a little too bold. There is room for error in this assumption, as most of the checklist’s Boston caps look suspect. Maybe he did the artwork himself 😉, as the text on the back of the card states that he is an accomplished sketch artist.

Part of being an artist is noticing detail, and there is certainly something to observe going on with the team logo in the lower left of each of the set’s Red Sox cards. Each of the set’s six series brought about different versions of the logo, which saw changes made to the sock’s cap, hands, forearms, ears, and smile. This is worth its own discussion and will soon be explored in detail in another post.