Gary Sheffield appeared in six different roles during his career (1B/SS/3B/LF/RF/DH). I propose adding a seventh as the defining role of Sheffield’s career: That of being a mercenary. Let me explain.

Sheffield, a nephew of Dwight Gooden, was signed by the Milwaukee Brewers and quickly made his way through the team’s minor league affiliates as a top-rated prospect. He was originally brought up as a shortstop, though poor fielding led to a shift to third. Sheffield had maturity issues at the time and made it well known that he did not want to play for a team he felt had insulted him, either through direct action, ineptitude (misdiagnosed injury), or through differing levels of attention and discipline applied to other players.

He was traded to the San Diego Padres in 1992 where they told him to focus solely on fielding. Sheffield promptly ignored this and perfected his windmill-inspired swing. In 1992 he became the only Padre not named Tony Gwynn to lead the team in batting average during the period 1983-1999. His two-year tenure with the Padres also saw him develop into a power hitter, further raising his trade value. A flurry of transactions followed. He moved on to the Florida Marlins, Los Angeles Dodgers, Atlanta Braves, New York Yankees, Detroit Tigers, and New York Mets.

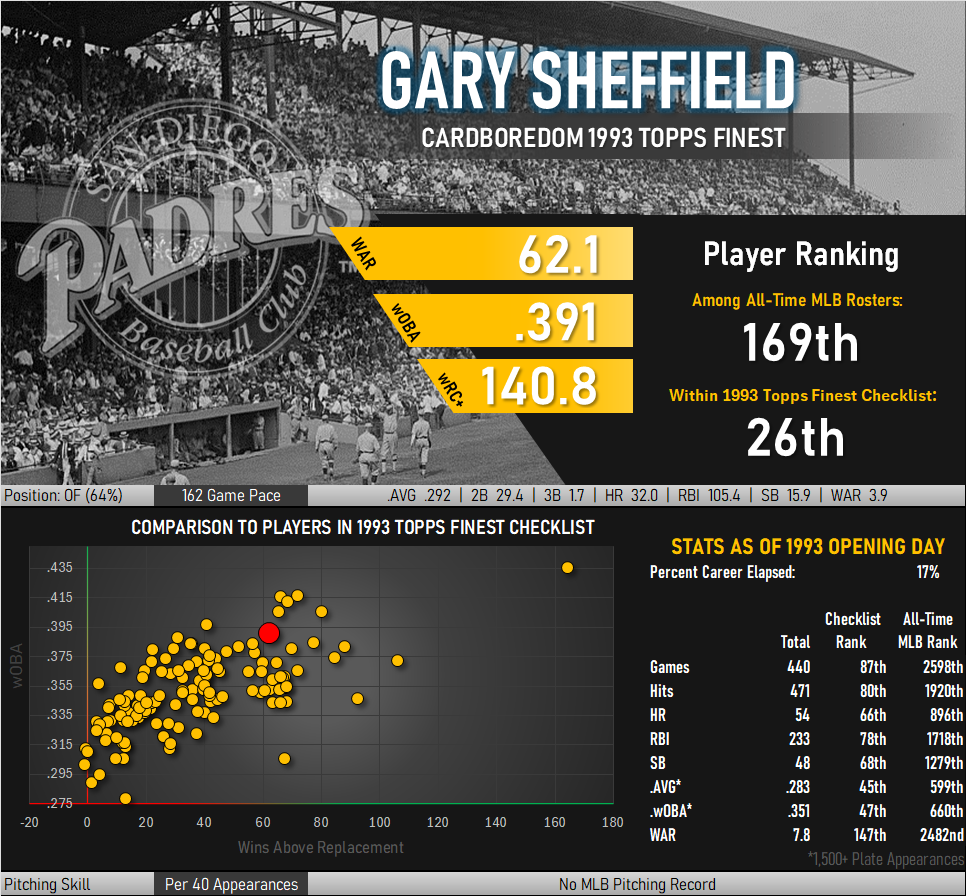

A few threads emerged in each move: No team knew where to put him in the field, each was making a serious run at the playoffs, and Sheffield didn’t seem too concerned about where he played. The first issue is only controversial to Sheffield, who seemingly thought he was a good defender. Bill James posited that he may have been one of the game’s worst defenders, certainly among those that played for such a long time. Sheffield didn’t stand out as much better at any of the other positions he tried, so teams began to slot him in wherever there was space. His Fangraphs defensive metrics show a fairly steady drag of ~2 WAR per year, highlighting the extent to which this was an issue.

This was an acceptable price for teams looking for a bat that would make an immediate impact in a race to get to the postseason. His offensive production more than offset massive defensive liabilities. If he played the entirety of his career as a designated hitter his WAR/162 games would have increased to a level exceeding that of Dick Allen or Mark McGwire. After leaving San Diego, Sheffield’s trade to the Florida Marlins gave him the longest single-team stretch of his career. The move culminated with the Marlin’s 1997 World Series championship. After that he was a World Series veteran for hire who spent 1-3 years at a clip with contending teams.

After a rocky start with the media and the management in Milwaukee, Sheffield closed in on himself. They weren’t going to help him, and he wasn’t going out of his way to provide them with anything other than lights-out hitting. Baseball became transactional, with teams more or less renting Sheffield’s services rather than fully incorporating him as part of the club. Sheffield did little to dissuade this, essentially making himself a baseball mercenary. A string of near-trades almost came to fruition as teams fought for his services. One such proposal even saw the Seattle Mariners offer Ichiro Suzuki to the Dodgers in exchange for Sheffield.

Sheffield was an amazing batter, and despite his defensive liabilities still ranks inside my top 100 position players of all-time. Ernie Banks, Eddie Mathews, Mel Ott, and Miguel Cabrera are all within a half dozen home runs of his total. His Baseball Reference adjusted OPS of 140 equals that of Alex Rodriguez, Duke Snider, and Larry Doby.

For what it’s worth (not much, all the hot takes on this website are free), I like mercenary style players. There is something meritorious about having a career that lives and dies by one’s own output. Short-term contracts provide flexibility and keep the competitive balance of the sport interesting. For all of that, I like Sheffield.

Sheffield on Cardboard

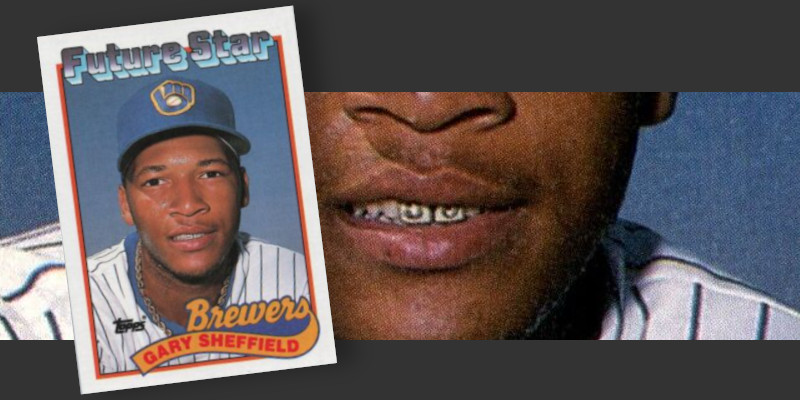

It doesn’t matter how rare, shiny, or photogenic a Gary Sheffield card is. There is only one* that will forever be the Gary Sheffield card: 1989 Topps Future Star #343. It is one of several rookie cards issued in 1989 and was made by the hobby’s biggest producer. Topps used an out-of-date photo for the most watched Brewers prospect in a generation, but that differentiated the card from all the others.

When Sheffield first signed a professional contract he received a $152,000 signing bonus. Soon he was a 17-year-old playing rookie ball with a Corvette and gold chains. He also sported new dental work, having had his initials inlaid on his front teeth. While this grill can be seen on at least one of his minor league cards (1988 Best El Paso Diablos #1), he thought better of the accessory when he reached the majors and removed it.

Newspapers loved reporting about spending habits of suddenly high-paid athletes, some with a hint of voyeurism and others with the schadenfreude of watching a financial train wreck in action. I get it. There is a learning curve that comes with money and it can be spectacular to watch as the quantity goes up. I grew up next to Langley Air Force Base, home of our nation’s 1st Fighter Wing. Anyone living near such an installation can answer this joke: What do you say to a guy barely old enough to drive sitting in a new muscle car? Answer: Thank you for your service.

This card commemorates a time when the first thing a young guy with some cash thought about getting was a fast car and gold accents on his teeth. It’s great, like looking at all the haircuts of family and friends in a decades-old photo.

Sheffield’s ’89 Topps is not the card that I am collecting. The card that brought him back to my collection is the ’93 Finest Refractor. This one was picked up at the same time I added my Jeff Conine and Albert Belle cards, making for one very good collecting weekend.