I’m getting older, a realization that has been coming on gradually then all at once when this fall I told one of the kids on my street to not step on freshly planted grass seed. Then again, that lawn is going to look fantastic in the spring. Those books about the age of sailing ships aren’t going to read themselves and I’m scaling back my love of spicy food challenges. It’s time to embrace my inner old guy.

Of course, I need some sort of a guide to becoming a grumpy old dude. Fortunately Will Clark is there to help. There is perhaps no one else in baseball who exudes as much of a “back in my day” vibe than the former San Francisco Giant.

Clark has never shied away from offering his thoughts on the game. His stature as one of the better players of his generation and his public facing role with the Giants gives his opinion a hot mic whenever he has something to say. A lot of what gets said seems to come across as the position taken by baseball’s old guard. Let’s see if I can start with Clark’s positions on various baseball topics and take his grousing to another level.

To set the stage, on April 12, 2022 the Giants spanked the Padres in a 13-2 blowout. The first 11 runs of that game came within the first two frames, making the outcome of the matchup reasonably certain. Already up by a score of 10-1 in the second inning, Steve Duggar received the “go” sign and promptly stole second base. The move prompted Padres and Giants coaches Mike Shildt and Antoan Richardson to exchange words with Richardson getting ejected from the game. Mauricio Dubón subbed for Brandon Crawford in the sixth and made his presence known by bunting his way onto first base. Newly installed Padres manager (and future Giants skipper) Bob Melvin let the opposition know he was not pleased with the Giants continuing to play hardball in such a lopsided contest. Little was said about what his club thought about utility man Wil Myers giving up a pair of home runs in a late inning bout of mop-up relief duty.

After the game San Francisco’s manager Gabe Kapler explained to reporters the many logical reasons behind keeping his foot on the gas pedal. They wanted to wear out the bullpen ahead of another game the following night, among others. Will Clark made the media rounds as well, appearing on the following morning’s sports talk show Murph and Mac and weighing in on what should have been a non-issue.

Clark: “As long as people like me are in the game, somebody is gonna get hit…We were taught a different way to deal with something like that…later on down the road, he’s [Kapler] going to have it happen to him, and he better accept it…Back in the day if somebody did ignore that rule [going easy on opponents when up by a huge lead] they got drilled. We even talked about it…He has set the rules out there. Now, he’s gonna have to live with it going forward.”

Let me see if I can spin this in a sufficiently proper old man fashion. ***steps up to microphone with newly acquired gray beard***

CardBoredom: Perhaps the Padres should stop asking to speak with the manager and simply play better baseball? The 10-run mercy rule goes away after T-ball for a reason: It only applies to children. As a fan, I want to see ballplayers giving 100%, not taking a night off because they are comfortable with their lead. Furthermore, the goal of any team should not only be to win, but to embarrass their opponents with better performance in the process. Those that lose by such a margin should be going home and questioning if this is really the game for them.

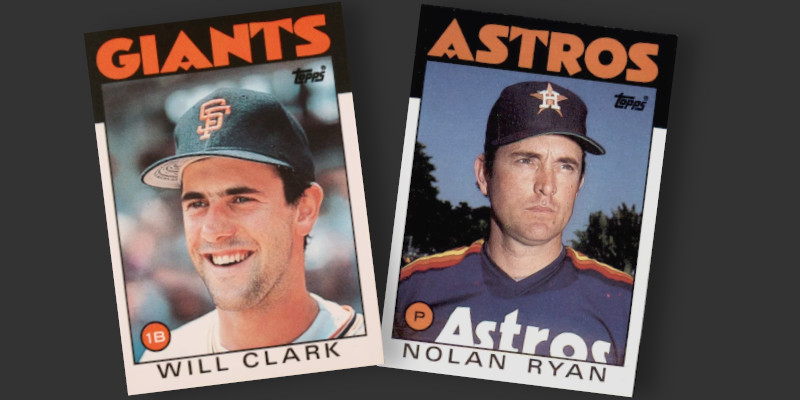

Now it should be noted that Clark, who appears in favor of giving fans less than 100% for the sake of propriety in these situations, suggested hitting batters on teams that have the audacity to do their jobs well. Forgive him, he’s growing a bit elderly. He began his MLB career by embarrassing nonother than Nolan Ryan in his 20th MLB season, hitting a home run in his first ever at-bat. On the first pitch. In the notoriously intense pitcher’s home park. Ryan followed up a few innings later by throwing high and inside, but not going as far as to hit the Giants’ new first baseman. The Giants would go on to win that game by 5 runs. If you’re going to hurt another team, do it where it hurts the most: In the standings.

Care to tell us how you feel about the proper use of analytics in baseball Mr. Clark?

Clark: “All you statistical guys that in the fin’ San Francisco Giants organization, you batter watch your ass too because you fuckers might be gone as well,” – Clark’s reaction to a changing out of some of the analytically minded parts of the Giants front office. “You’re coming up to me and you’re telling me on a piece of paper that I’m wrong? Fuck you. I’m sticking with me. I ain’t sticking with you.”

CardBoredom: Will Clark is an expert baseball player with a .303 career batting average. That commands all the respect that should be afforded to a guy who is correct 30.3% of the time, every time. I am firmly in the pro-analytics camp, but Clark is too polite to state what may be the real problem: While 30 MLB teams have dedicated analytics programs, there are only a handful that can be materially better at it than the others. Maybe the Giants just weren’t as good at this than the other teams.

I’m cutting and pasting Clark quotes without their full context, and doing so with a subject that requires some (plug your ears Will) nuance. We’re all focused on what I call “baseball card stats,” numbers that show up in a static format on the back of a small piece of cardboard and represent the entirety of a season or career. While these figures do provide a solid place to begin an assessment of a player’s ability, they can easily come up short in their near term predictive abilities. And what more is a single at-bat other than an extremely short term game of guessing how each party to the encounter will behave?

I arrived in the world of quantitative analysis via the finance sector and there is a relevant aspect of the argument over analytics that Clark’s comments come close to touching on. Some of the most successful algorithmic trading systems have been built around the idea of automatically determining the state of the environment in which an action is contemplated and adjusting strategy to best take advantage of the landscape (see Markov chains). The environment or state of a baseball game changes constantly. Shifts in the ball-strike count rapidly shift odds of the outcome of any particular plate appearance while the number of outs on the scoreboard exerts a more than linear pull on the progression of an inning.

Every team has a serviceable database of “game states” from which to draw strategy and traditional analytics is very good at dictating which plan of action should be used when the state of play can be described in a quantitative manner. Problems arise when this universe of possible game states fails to reflect what is happening on the field. A good manager (and astute players) will take notice of a defensive player slightly favoring one leg over the other or a pitcher tipping his pitches.

Good analytics teams and the managers employed to direct strategy need to be on the same page when it comes to understanding which strategy should be employed in any of these states. Teams that win will have their analytics staff setting the baseline strategy for any particular state of play with managers given the freedom to openly deviate when they can articulate a qualitative reason for doing so. While each team surely has the math part down cold, the degrees of freedom given to managers who know when to use it is surely something affecting the outcomes of games. I think Clark, who is part of the Giants organization, is emblematic of differing layers of the club not having the freedom to push back against each other. He just needs to state why using more than his favorite two word retort.

Clark’s disdain is not solely limited to guys who try hard all the time and people with too many R-coding references in their LinkedIn profiles. What about the guys who could not adjust to playing in the era of defensive shifts?

Clark: “As far as the shifts go, it’s great for the defense because they’re playing the odds and these idiots that are in the batter’s box don’t make any adjustments. And taking that a step further, that’s like these guys that hit 20 homers, maybe 25 at the max, and he’s gonna strike out 200 times. That’s not a hitter, you have no pride in your craft, you don’t work on anything, all you do is go out and try to hit the ball out of the ballpark, that’s all you do.”

CardBoredom: I completely agree. That’s not a hitter, that’s a trip back to the dugout. Here at Norfolk Tides games we serenade these guys with a “left right left” marching cadence as they return to the bench. Launch angle and swinging for the fences work great when the odds are in the batter’s favor. Guess what? Those odds shift along with the placement of the defense. Too many guys sulk at how they are now a .243 hitter (the 2024 MLB average) instead of adjusting their swing to hit the ball to the side of the field with no defenders. Will and I would be eating early bird dinner specials together if not for getting crossed up earlier on how to handle teams stealing bases in blowout games.

That’s a shame, because Will Clark has been known to pick up a check or two at dinner. Clark has told a story in which he encountered MLB umpire Angel Hernandez at a bar and then paid off his tab. As Clark tells it, “The rest of my career, every time I had Angel Hernandez behind the plate, my strike zone was fucking that big right there [indicating a small square with his hands]. All because of $20 worth of beer.”

Some may say I selectively chose words to put in Will Clark’s mouth. Perhaps. If asked for his thoughts directly on these subjects he would probably keep to the same overall theme but state it in a different way. I am certain there would be much more swearing.

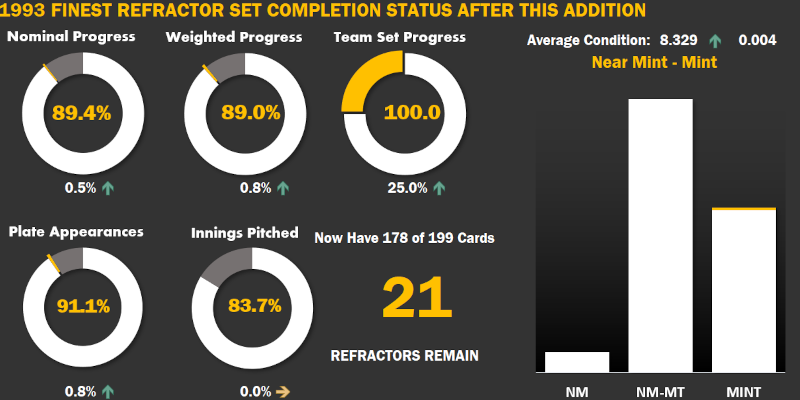

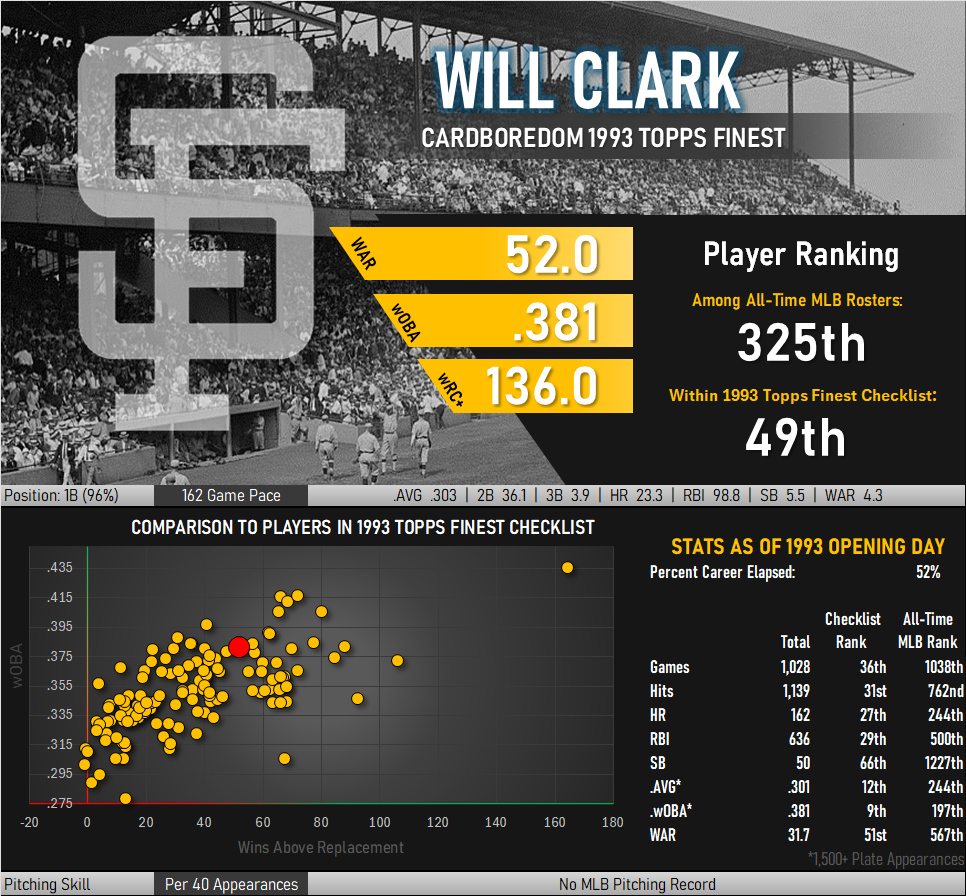

Shown above is my statistical overview of Clark’s career. I have him ranked as the 325th best baseball player of all time, a position that feels about right at somewhere just outside of where you could draw the dividing line for Cooperstown. I remember him as being an absolutely huge name in the sport for the first five or six years of his career, before just falling away from the headlines for the rest of his career.

In hindsight I realize he didn’t really fall off too much, he was just overshadowed by a new generation of monster first basemen led by names like Frank Thomas. Looking at the chart above, the 1993 season marked almost to the day the halfway point in Will Clark’s MLB career. From his 1986 debut to the last plate appearance of 1992 he batted .301, generated a wOBA of .381, and averaged 25.5 home runs per 162 games. The second half of his career saw him hit .305, keep his wOBA steady at .381, while still averaging 20+ HRs per 162 games.

Clark’s role as one of the better first basemen in the game might actually be holding back his reputation among fans. He was played at first and had 25 HR power and a .300 batting average. Thomas and others were busy generating 40+ HRs with averages thirty points higher. The thing is, Clark was a first baseman because that role was open when he first broke into the lineup. Although he played all 1,889 of his MLB games at first, he acquitted himself well at other infield positions in college and other levels play. He generated 52.0 career fWAR during his MLB tenure, a number that incorporates a negative adjustment just for playing first base. What if he had played second base instead at the same level of competence? Such a change is worth 1.5 WAR per 1,458 defensive innings played, enough to shift his 52.0 career WAR to 68.7, well ahead of Ryne Sandberg.

A Few Will Clark Cards

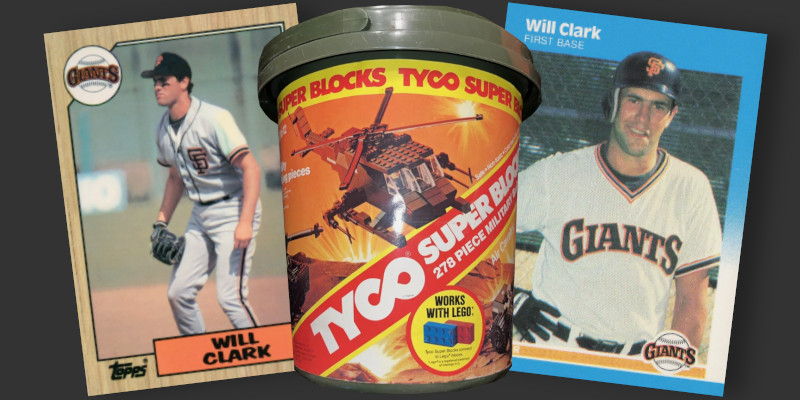

Now an honorary member of the “Old Guys Club,” I don’t remember too many of the Will Clark cards that inhabited the first incarnation of my collection that overlapped with his playing days. However, I distinctly remember traveling to visit relatives in Charleston, West Virginia in the summer of 1991. A teenage cousin took my brother and I to a card show held at a local mall. She purchased a 1987-88 Fleer Michael Jordan basketball card. I had been given $20 in spending money by my parents and spent $3 on an ’87 Topps Will Clark rookie before venturing into a toy store to spend the balance on an army helicopter kit manufactured by Lego competitor Tyco. On that same trip my aunt, who worked at an “inspirational bookstore” brought home a video from a series that was supposed to teach us kids morals using popular topics. This particular one focused on a kid that was considering lying in order to get a Mark McGwire rookie card, which was described in the plot as being the “most valuable card in the set.” Seeing an ’87 Fleer card on the screen, I promptly went into full fledged “well, awkshully…” mode and tried to explain that the video was lying as Will Clark’s rookie was obviously better.

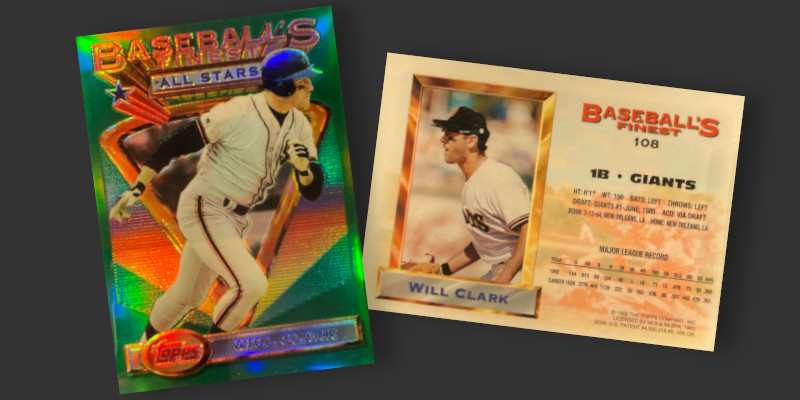

As you can see, I can get quite pedantic at times. There’s no use in stopping now. Did you know that Will Clark is one of the 31 players wearing eye black in pictures used on the fronts of ’93 Finest cards? The number is actually 30 if you exclude Gary Sheffield due to his apparent attempt to remove the stripes midgame.

This is one of the refractors that feature something I feel should have been a conscious design element for every name in the checklist. Between the images on the front and back Clark is shown wearing two versions of San Francisco’s uniform. In fact, these appear to be the same designs employed on the Topps and Fleer rookie cards I became so acquainted with in West Virginia.

One more item before this post ends: I quite enjoyed a local writer’s encounter with Will Clark at a Richmond Flying Squirrels game, the Giants’ AA-level minor league team that represents the closest professional baseball action to my home.