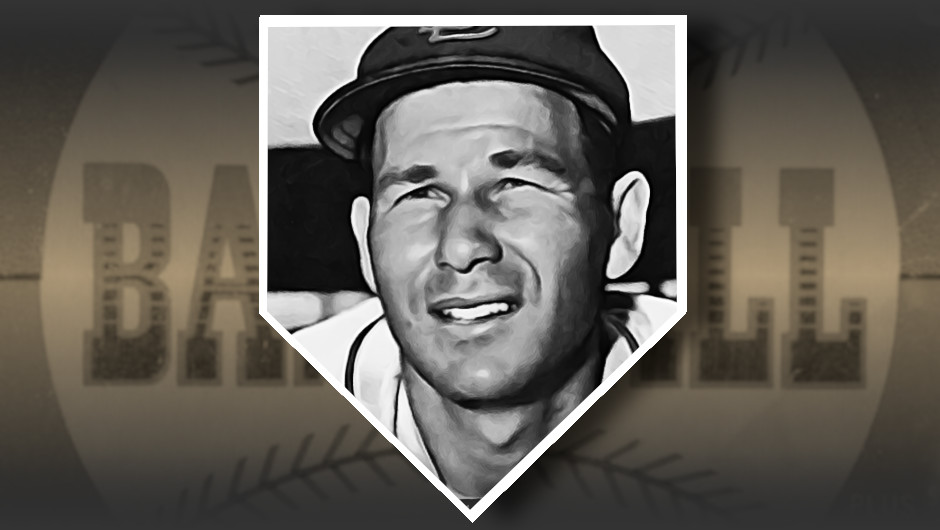

Looking up the history of a ballplayer who took the field half a century before you were born can sometimes be hit or miss. Sometimes all you have at your disposal are some stats, generic sounding biographic snips from the back of baseball cards, and two or three nondescript lines on Wikipedia. Other times you are greeted with a near unanimous consensus in the writings of people who surrounded your research target throughout their tenure. Former Cardinals and Phillies infielder Solly Hemus definitely falls into the latter category.

By the time Hemus took his first steps onto a Major League diamond he had already established a reputation. He played sandlot baseball after school in the 1930s with fellow San Diegans Ted Williams and Ray Boone. After returning from naval service in World War II he was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers. While there he argued with his minor league manager and was quickly dropped from the team. The St. Louis Cardinals picked him up and moved him through several levels of their vaunted farm system.

It was in the St. Louis organization that he turned his argumentative nature to his advantage. He pestered opposing pitchers, drawing walks and getting hit by pitches. He was quick to dispute calls with umpires, a trait that would follow him throughout his playing and managerial career. His verbal assaults on umpire crews made appearances in the first successful baseball memoir, pitcher Jim Brosnan’s 1960 The Long Season. In the book, which led Jim Boutoun to write Ball Four a decade later, Brosnan likened the thinly built 5’9″ Hemus to a mouse berating an elephant.

Hemus could be divisive among his own teammates. The Cardinals were a club in transition in the late 1940s and early ’50s along with the rest of the newly integrated sport. Prior to Hemus’ arrival the club had infamously threatened to refuse to play against Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers. A vocal contingent made their animosity known to black players early in the decade while a couple of their pitchers intentionally threw at batters. Some players, such as Stan Musial, were reportedly incensed at the actions of these teammates, leading to back and forth tension in the clubhouse throughout the decade. Hemus was one of the players whose derisive language increased strain.

In 1956 the Cardinals traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies, another team with a troubled racial history. The following year, Hemus may have been used by manager Mayo Smith to send a message to the club. Down 3-1 in the team’s April 22, 1957 game Hemus hit a double, placing himself as the potential tying run on second base. Smith called for a pinch runner, replacing the former NL run scoring leader with John Kennedy. Kennedy, a black man, was making his Major League debut just over a decade after Jackie Robinson had taken the field and a season after Robinson’s retirement. Of course, Philadelphia team owners remained opposed to truly integrating the team and had signed Kennedy only to a 5-game token role. With manager Smith’s paychecks signed by this group, he aimed his Kennedy’s limited replacement roles to ones in which the antagonistic Hemus would be the one taken off the field.

Hemus returned to the Cardinals in a 1958 trade, was released three weeks later, and signed again with the team the following spring as their new player-manager. Hemus brought his usual style to the new role, getting ejected from dozens of contests by fed up umpires in the process. He also continued to demean black players, ones that he was supposed to be building up in his new role. Hemus claimed he didn’t mean to come across as racist, arguing instead that he had an abrasive style of motivating people. Bob Gibson, likely the best pitcher to ever wear a Cardinals uniform, wrote about Hemus in his 1994 autobiography that “…either he disliked us deeply or he genuinely believed that the way to motivate us was with insults.” There is plenty more about this in the writings of Gibson, teammate Curt Flood, and other works covering the period. Hemus doesn’t come across as a particularly sympathetic character in any of it. Hopefully he learned over time, but nearly all that I can find written about him originates from his actions early in life.

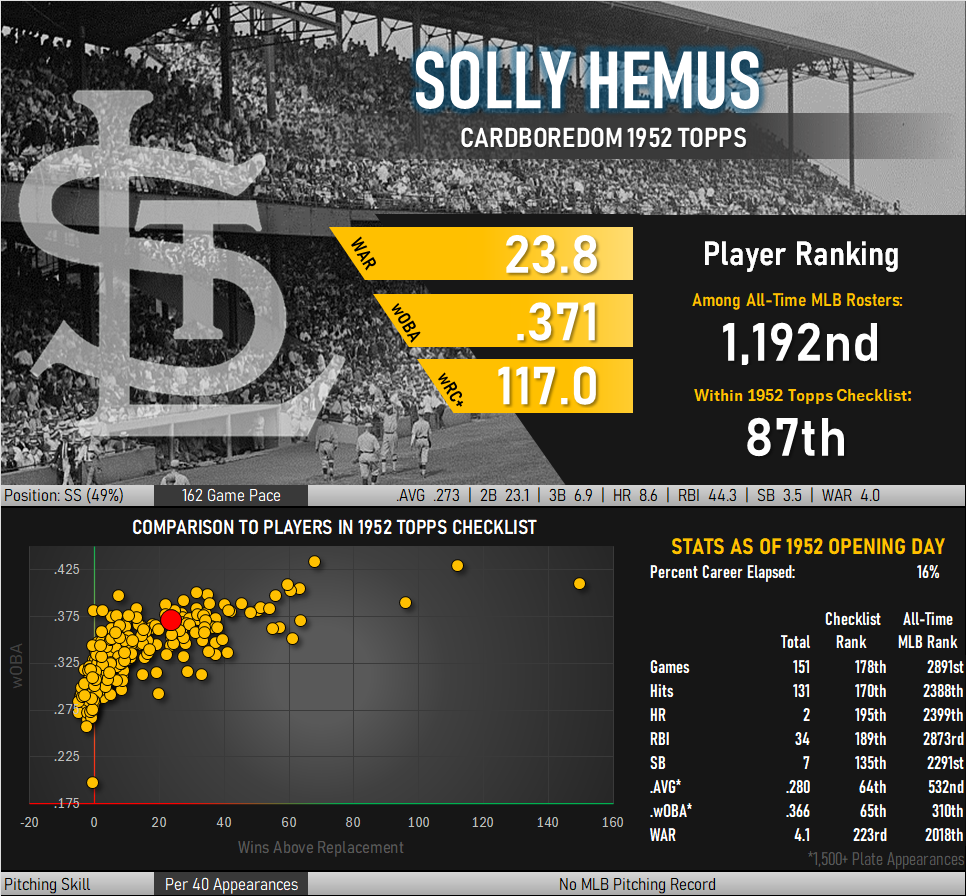

Hemus was pretty good when his mouth was closed. He averaged 4 wins above replacement per 162 games played over the course of his career, just ahead of the lifetime paces of Rafael Palmeiro and Dom DiMaggio.

Solly Hemus Disappears from ’52 Topps

Known to be a hard case on the field and in the manager’s office, Hemus could also get ornery with guys in suits. Baseball cards were booming in popularity in the early 1980s and Topps wanted to highlight its three decades of cardboard history by reprinting its famous 1952 set. The card manufacturer produced a limited edition, 402-card run of its most popular issue in 1983. The cards feature improvements over the originals, ushering in the printing technology that would underpin the firm’s popular “Tiffany” cards over the next decade.

The 402 card checklist differs from the original 407 card release due to contractual problems. As an upstart in the unsettled world of to publicity in the 1950s, Topps had played fast and loose in obtaining permission to produce cards depicting baseball players. With an active player union, two new corporate competitors, and decades of additional courtroom precedent the firm could not afford to be as cavalier as it had once been. Each player (or representatives of sometimes long-closed estates) were contacted to arrange a new contract and a payment of several hundred dollars. Five players, all still living at the time, refused Topps’ entreaties. One of these was Solly Hemus and the failure to reach an agreement led to his 1952 card #196 being omitted from the commemorative set.

Hemus and Topps apparently came to terms a few years later. Topps brought back the reprint idea in 1991 with the issuance of Topps Archives, a glossy reprinting of the company’s follow-up 1953 edition. Hemus appears as card #231 in the 1991 edition. Billy Loes was the only original 1983 holdout who refused to cooperate.

Solly Hemus Previous Appearance in ’52 Topps

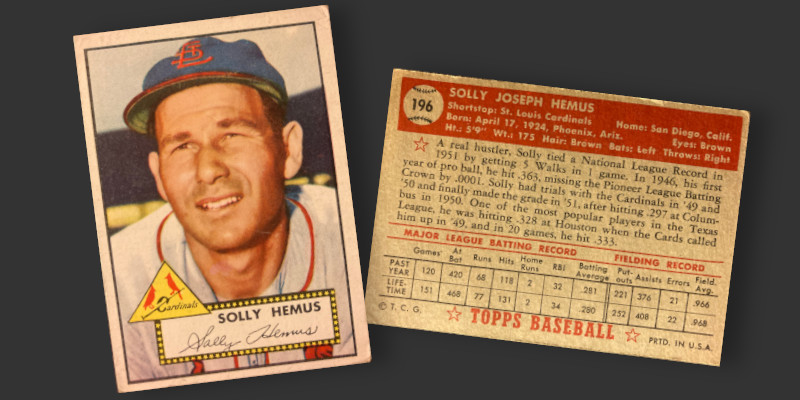

The future Cardinals manager appeared promising when his cards spilled out of the fourth series of 1952 Topps wax packs. He had just finished his first full season in the big leagues with a healthy .288 batting average. The text on the back of the card highlighted his ability to get on base with a description of his drawing five walks in a single game as a rookie. As pictured on the card, Hemus was half way through a 1952 season in which he would finish as the runs scored leader for the National League. The next year he led the league in getting on base via being hit by pitches.

The card itself looks good. The condition of this particular example is better than most in my collection. The centering is a bit off in a non-distracting way while the corners show moderate wear. Solly is well lit in the photograph, something not seen in many similarly styled portraits in the set.

Solly has a skeptical look on his face, though this is likely the result of facing the sun while getting his picture taken. I like him from a statistical perspective, but his personal foibles make my face mirror the look on his when viewing the card.