Matt Batts has been described as a lot of things. Talkative. Genial. Headstrong. Bench Jockey. Chirpy. Journeyman. Backup. Frequently traded. Sometimes words alone were insufficient, as in 1948 when Red Sox manager Joe McCarthy kicked his own catcher in the seat of his pants after losing an argument over a steal of home plate.

Opposing players probably had plenty of terms for Batts as well. His specialty was needling opponents, either from behind the plate or from the bench. There was no keeping Batts quiet and he had a reputation for making himself heard across a diamond.

Don Newcombe had a descriptive phrase in mind, calling Batts and his teammates “real rednecks” when remembering racially charged jeers originating from their bench in a minor league game. I came across Newcombe’s recollection when reading up on Batts and thought, “Oh no, this is going to be another disappointing look at a ballplayer that turned out to be have all sorts of problems.” Batts came up through the infamously segregated Red Sox organization, playing 5 seasons with the parent club and moving on to other teams 8 years before Boston finally admitted a black man to the team.

Things were not looking up for Batts’ reputation when he expanded his taunts to Al Rosen’s Jewish background. Rosen, an award winning boxer, called time during a 1950 game and headed straight towards Batts in the Red Sox dugout. Batts’ fellow Sox carried their catcher away for safety.

Serving only in a backup role, Batts’ primary responsibilities to this point had been to infuriate opposing teams with whatever he could get within earshot. A slow start (.138 batting average) in 1951 led Boston to trade him to the St. Louis Browns. This move was the catalyst for a lasting change, one that just may have offered some redemption.

Game Respects Game

Batts was traded in late May and would appear in 79 of the Browns’ remaining 126 games. Importantly, 10 of these contests featured Batts catching for Satchel Paige and by the end of the season Batts was the primary catcher for pitching legend. Paige, of course, was black and as an American League opponent had been on the receiving end of Batts’ chirps in 5 prior games. Yet, for all this, later accounts of Batts’ career always paint his pairing with Paige as the highlight of his career. I think this is indeed a high point, but little is said about why.

If anyone could appreciate the trash talking skills of a ballplayer it would be Paige. He was a master of the art and wove it deeply into the fabric of his game. He would talk to batters, telling them what pitch was coming with the implication that the information would be of no use to a flailing bat. He gave names to his pitches that made them sound as mythical as the nose art on WW2 aircraft. He was always good copy in the newspapers, developing an excellent set of backhanded compliments for opponents to read. Paige famously didn’t have to only rely words to unnerve batters. He would hum musical tunes to himself on the mound as he worked, irking batters hoping to make him feel his skills had long ago left him. His exhibition appearances are filled with tales of him telling outfielders to sit on their gloves or abandon the field altogether as their services would not be needed.

It is against this love of confrontational banter that Paige and Batts set to work, engulfing batters in a crossfire of insults. The results were as follows: With Batts Paige posted a 1-1 record with a 1.35 ERA and 3 saves. Without him Paige was 2-3 with a 6.43 ERA and 3 saves. They made a good team, with Batts’ mouth augmenting Paige’s challenges to batters and Paige’s decades of experience helping guide the defensively challenged catcher. Batts allowed an average of 0.09 passed balls, 0.09 errors, and 0.22 wild pitches per 9 innings of defensive work during his career. In St. Louis Browns games he averaged 0.15 passed balls, 0.15 errors, and 0.08 wild pitches. He improved to 0.00/0.11/0.11 when Paige was on the mound. They made each other better, and it wasn’t just an on the field gain for Batts.

It is around this period that reports of unsavory aspects of Batts’ trash talk seem to die away. The insults became less about people and more about their skills on the field. Unlike other players, such as a handful of the era’s St. Louis Cardinals, Batts seemed to move past racial taunts as his career progressed. By the time his obituaries were printed a decade ago, Batts’ was almost universally remembered as Paige’s catcher and a once promising prospect rather than as another guy whose actions get weakly defended as being, “just a product of his era.” Working with Paige he seems to have made it past this.

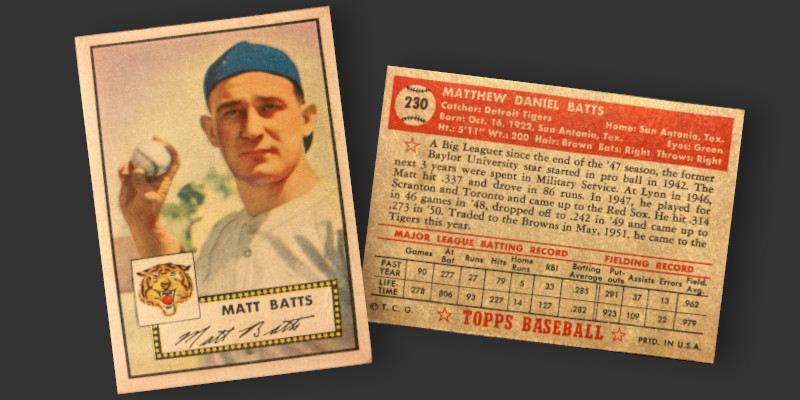

Be Careful, Those Corners are SHARP

Most of my 1952 Topps cards are pretty beat up, averaging out to somewhere in the range of Fair to Good in grading terms. My Matt Batts card does not look like the rest, and if it holds to the same chirpy tendencies of its namesake the card is likely making fun of the others. This card’s corners are razor sharp. There are no traces of damage along any of the edges. Centering, always a challenge in collecting this set, is fantastic on this card. There’s a faint wax stain on the back of the card, but that only reinforces the “pack-fresh” impression generated by this little piece of cardboard. Unfortunately, there is the world’s smallest wrinkle running from the bottom of the card into the edge of the nameplate on the front. While I still consider it to be pack fresh, that pack apparently rode home in someone’s pocket.

The photo is a fantastic choice. The backwards hat shows the way catchers who catch wear one. Lots of backstops in the set appear to have been photographed just after practice without their gear and are obviously posed to look like they were doing something.