I published my first words here at CardBoredom in 2021. I’ve paid pretty close attention to the availability and sales of various baseball cards in the ensuing years, but perhaps it has been an exercise in wasted time. Instead of writing about little bits of cardboard, what I should have been doing was attending art auctions in Spain.

Three weeks prior to my initial post, Spain’s Culture Ministry stepped in to investigate a series of 17th century artworks attributed to followers of Jusepe de Ribera that were slated to be sold for as little as €1,500 each. The art world, particularly in the middle of the previous millennium, was rather tight knit. While it seems as if major advances in style and technique sprang everywhere out of nowhere, much of the progress came as artists improved and one-upped the innovations of their contemporaries.

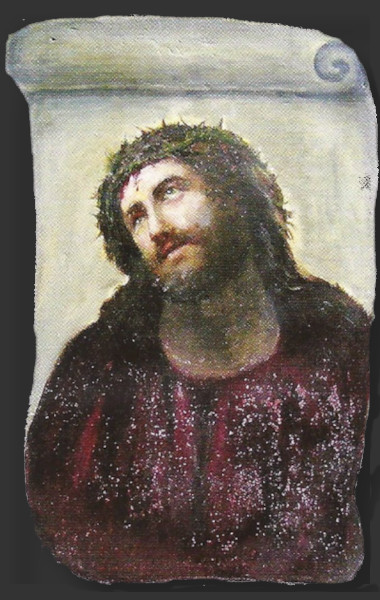

Ribera was accomplished in his own right, and I find it incomprehensible that items connected so closely to his works would have seen final bids anywhere close to the lowly figure quoted in reports of the proposed sale. Like other Baroque artists, he had built upon the techniques used by other influential painters. This included Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, and it was the similarities between Ribera’s reputed Ecce Homo (“Behold the Man,” shown below) and those of Caravaggio that drew the attention of authorities.

Multiple items were pulled from the auction and export bans put in place as experts from Madrid’s Prado rushed make their inspections. In what is still a contested call, the museum pronounced this particular piece to be an original Caravaggio. A definitive attribution is tricky, amplified by the fact that Caravaggio was on the run from a murder charge during the period in which this was painted. Considering secretive pricing and a relative paucity of publicly reported Caravaggio transactions, anything attributed to the artist is suspected of potentially crossing the nine-figure mark if ever brought to market.

Not every artwork looks this well preserved. In fact, this nearly 10 square foot canvas underwent some restoration and conservation work during its period under study. While one can find ways to quibble with the attribution, I have not seen any complaints about the care shown in its manner of preservation. Another work located 200 miles to the northeast in Zaragoza and also bearing the name Ecco Homo was not so fortunate.

Painted by Elías García Martínez in 1930, the fresco adorned the walls of a church. Fresco works require paint to be applied to wet plaster which then sets the image as it dries. The passage of time and ambient humidity damaged the painting, causing portions of the image to flake away.

A local woman, who, by all accounts, was not versed in conservation methods, set about “restoring” the image on her local church wall. The time consuming process apparently tired out the octogenarian as she elected to leave town for a two week vacation before completing her work. Based on the results, I would have left town as well.

When her handiwork first came to the wider population’s attention it was assumed that vandals had attacked the painting. As a local investigation developed, the story of the well meaning (but blundering) amateur came to light and the Internet collectively changed the name of the work from Ecce Homo to Ecce Mono (Behold the Monkey). She defended her skills by claiming this was still a work in progress, though it should be pointed out that further restoration work was quickly assigned to someone else. Hopefully security checks her for hidden paintbrushes if she ever visits the Prado.

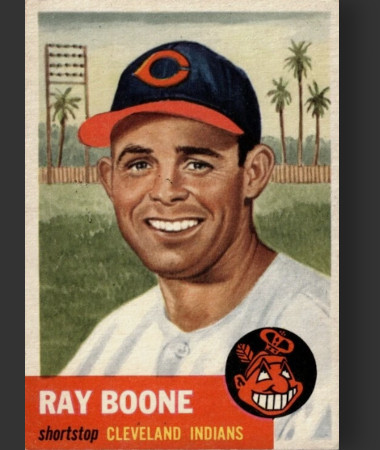

You don’t have to visit your local art gallery or a hillside church to view artistic touchups. Topps gave us decades of terrible jersey edits throughout its baseball card sets. The card manufacturer even came close to creating its own “Ecce Mono” in 1953 with this inexplicably simian portrayal of Ray Boone. Why are his ears visible from every angle? Why are his eyes looking slightly in two different directions? Why are there palm trees in Cleveland? Why does his cap cast a shadow on his forehead but not have one on the underside of the bill? Just…why?

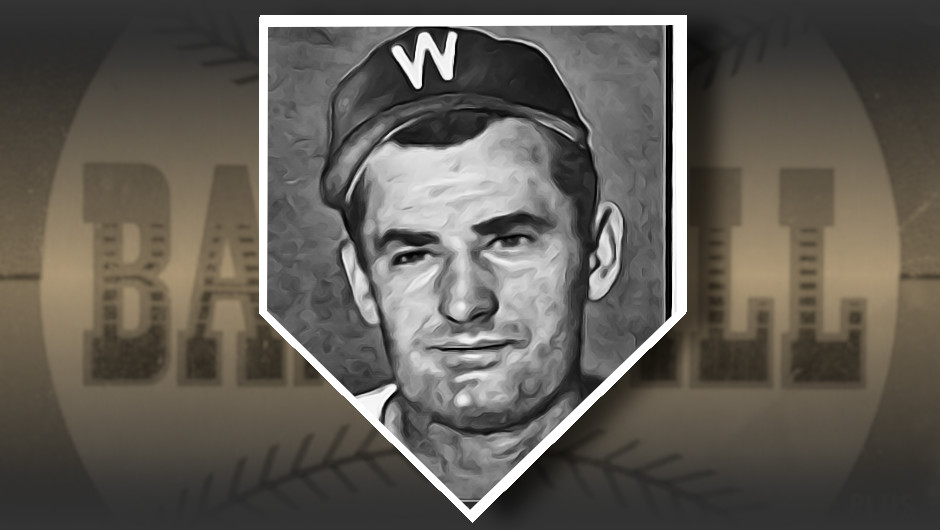

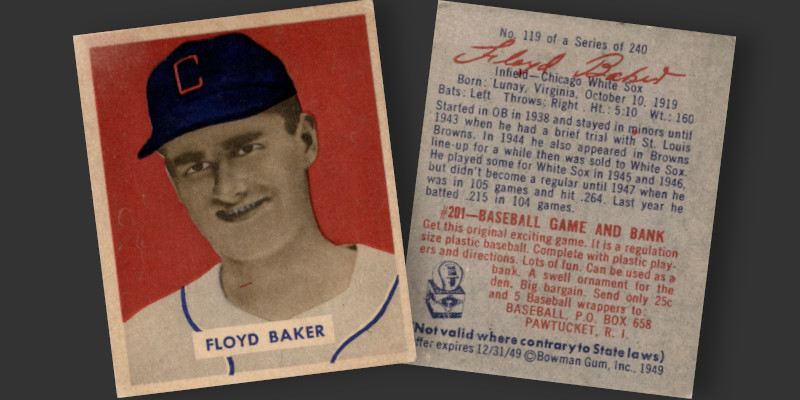

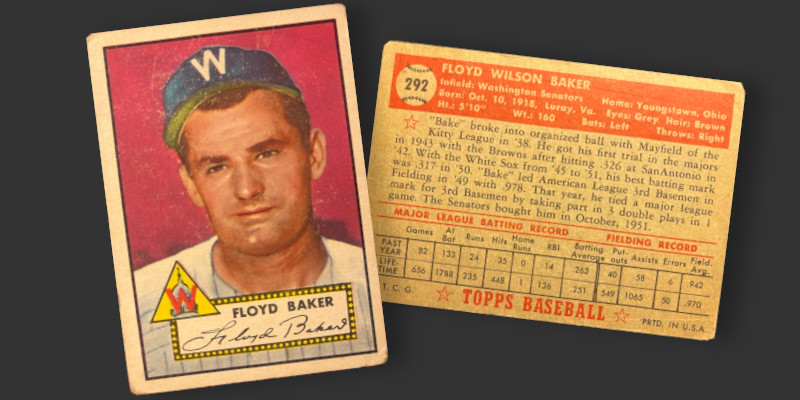

This wouldn’t be the first postwar baseball card touchup gone awry. Four years earlier Bowman had modified a black and white photograph of infielder Floyd Baker so that he would appear to be wearing a Chicago White Sox cap.

That’s not all that was done to the image. Look closer at his face, where some heavy handed editing was applied. Look at those dark, sharklike eyes that seem to be all pupil and no iris. Look at how someone physically drew an outline around the eyes, as if he were Egyptian royalty or a comic book character. There is some play in the shadows as well, with the eyebrows looking suspiciously bushier than the real-life version of Baker. His teeth are oddly individually visible in such an indistinct picture. Honestly, it looks more like the Internet’s Troll Face than Floyd Baker.

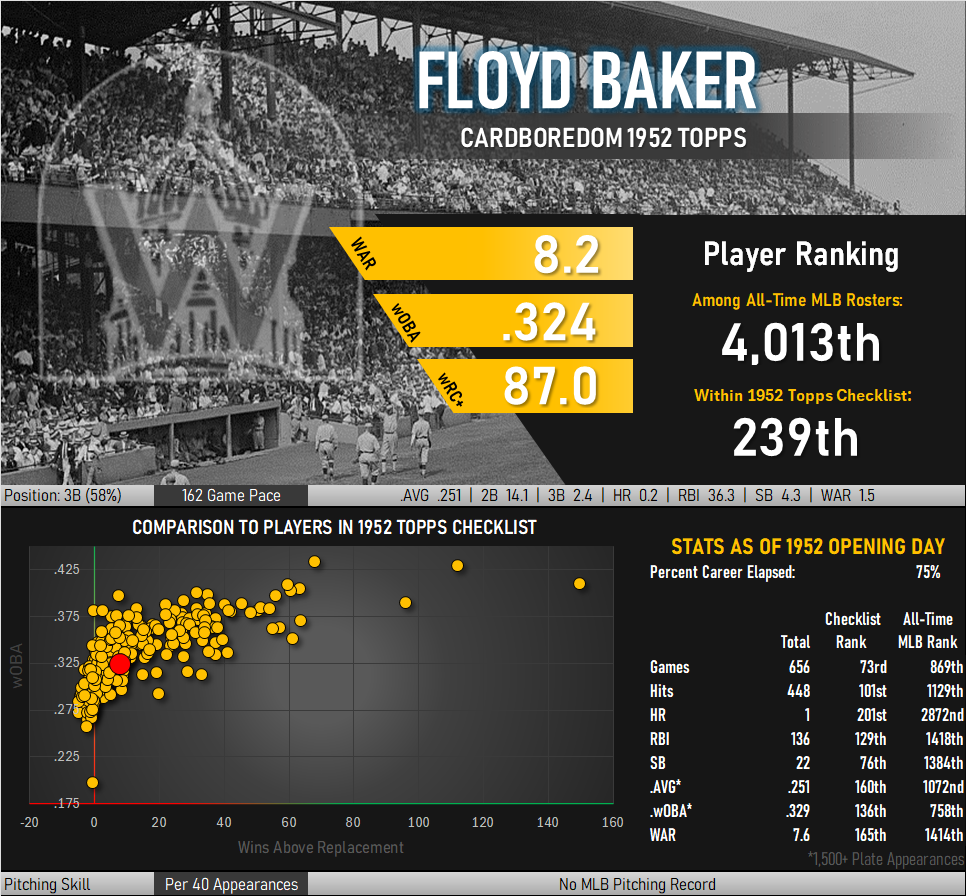

Although Baker appeared in both issues, the visual appearance of his card wasn’t going to make or break Bowman’s baseball card set in its 1949 turf war with the Leaf Candy Company. He was a defensive-minded infielder that made many of his appearances as a late inning replacement. He has the dubious distinction of having one of the absolute lowest home run production rates as the result of hitting a solitary dinger in 2,694 plate appearances. If being tied with Bartolo Colon for career homers wasn’t enough, Baker’s round trip came about only when the White Sox temporarily moved the outfield fences to be 332 feet from home plate. Baker’s was one of 14 Comiskey home runs hit inside a 24 hour period before the makeshift wire fence was scrapped.

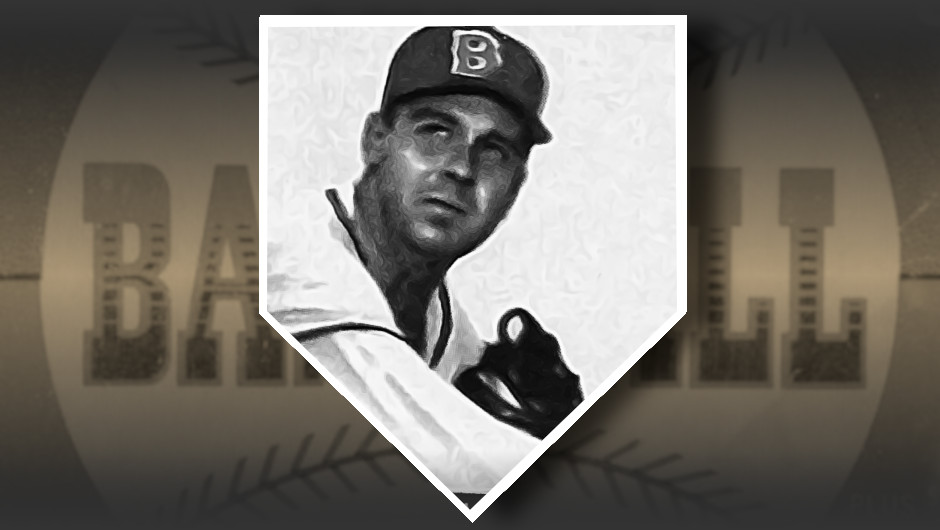

Baker actually had a career year in 1949, getting more than 100 hits and seeing action in more than 100 games. He batted over .300 in an abbreviated 1950 campaign before returning to his usual part time role. He looks a bit skeptical of Topps’ photographer on his ’52 baseball card. Given the experience with Bowman, that was to be expected.

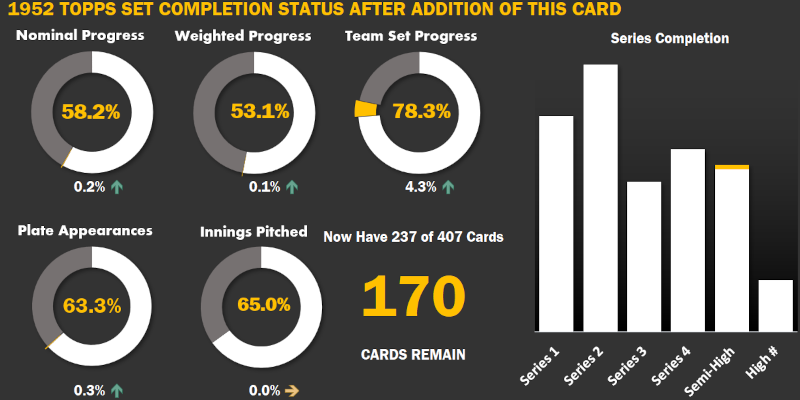

This card can be found in the sometimes challenging fifth series issued deep into the season. I picked up this fair condition copy via COMC.