Bill James Said: “Martinez, one of the best hitters in baseball, severely pulled his hamstring in April, tried to come back too quickly, and then a) didn’t hit, and b) re-injured the hamstring.” If you look back at Edgar’s career stats, the 42 games played and .237 average in 1993 stick out like a sore, um, hamstring. Yet he still drew enough walks (28 in 165 PA) to give him a .366 OBP and a perfectly average 100 OPS+. I feel like most fans still don’t grasp just how good a hitter he was.”

Each year on September 30 there is a celebration of freedom of expression in which people say things that would result in legal (or extralegal) punishment if uttered in large parts of the world. Today I took a few moments to reflect on having the freedom to say out loud that someone’s imaginary friend doesn’t exist. Thousands of years ago you couldn’t say that about Zeus, Osiris, or Baal, and modern times have their equivalents. I don’t know how many people actually mark this occasion, but I know it would be a sad state of affairs to not be able to mouth off about something like this. I wanted to post this on last year’s Blasphemy Day but didn’t get around to it in time.

Setting that aside, let’s look at some baseball blasphemy. I think this the recent expansion of designated hitters to both leagues is great. Purists (zealots?) have railed against the introduction of the DH role since its introduction to the American League in 1973. Most of the opposition comes from groups that view early rules of the game as sacred and untouchable, conveniently omitting the positive impact of improvements such as overhand pitching and counting fouls as strikes. Resistance to change lies not so much in keeping the game in its original form (Rounders? Lapta? La soule?) but rather keeping it the way people remember from their childhood. The best defense of avoiding a DH rule lies in having a keen interest in managerial strategy. Having never heard of a Little Leaguer hoping to one day be a manager and having never sat next to a fan at a game rooting for a manager, I have significant doubts about the strength of this argument.

Designated hitters bring nothing but good to the game. First, they keep good players in ballgames. Pitchers are only removed when their arms are in jeopardy or are losing effectiveness. Nobody wants to see Clayton Kershaw taken off the mound an inning early just to keep him from batting. Pre-DH rule pitching strategy revolved around keeping pitchers out of the batters box because they are such historically lousy hitters. A full-time DH takes the weakest part of the lineup and potentially transforms it into one of the strongest. Dead spots in the lineup are resultingly smaller, adding excitement. Aging superstars who can still mash the ball but no longer can run down fly balls are able to keep playing. Again, no fan of the game loses when they get to see someone like Albert Pujols or Frank Thomas get extra time tacked on at the end of their careers. The DH rule also removes poor fielders from defense, making the addition a net positive on pitching, hitting, and defense. Every aspect of the game is improved.

Taking the Designated Hitter Rule to Seattle

Boston’s Ted Williams, possibly the greatest hitter of all time, would have benefitted from the DH role given his subpar defense and hatred of jeers from the left field Fenway bleachers. His offense and impact on the game was so legendary that Boston named one of its major underwater tunnels after Williams. Interstate 90 terminates with this tunnel and is shielded by the Green Monster as it passes Fenway’s left field. I-90 continues across the North American continent, ending at the parking lot of another baseball stadium in Seattle. As drivers approach T-Mobile Park to watch Mariners’ games, they exit the Interstate and find themselves driving on Edgar Martinez Drive, a road named after potentially the best designated hitter of all time.

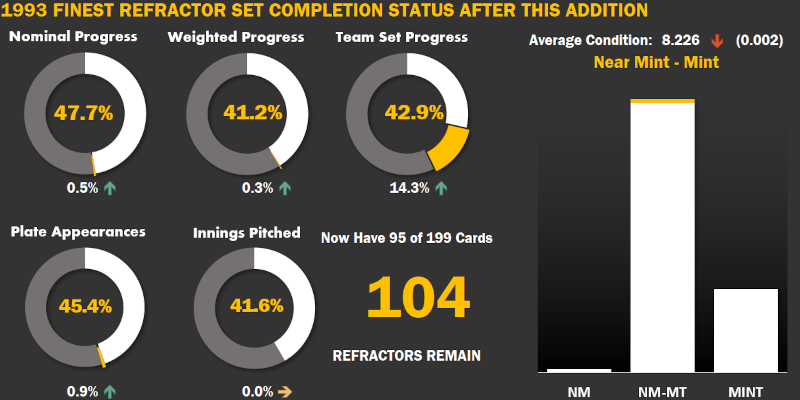

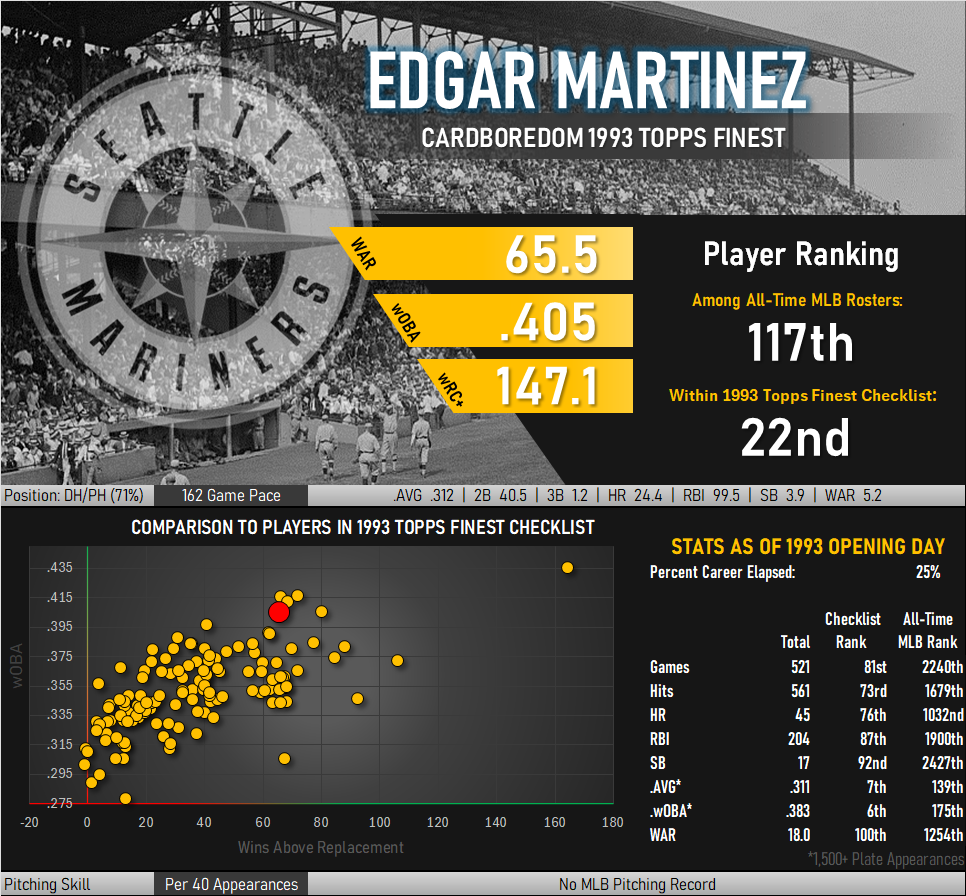

Martinez snuck up on baseball and was initially passed by when scouts came to look at a talented cousin. He played in semi-pro games between shifts at a furniture store and a General Electric factory. He managed to get in front of scouts when he pulled an Eric Anthony with a 1982 Seattle Mariners tryout session. The team didn’t realize how good a player they had with Martinez and didn’t give him a taste of Major League pitching until 1987 and a permanent roster spot until 1990. He was almost 25 years old when he made his debut and didn’t play his 100th game until the year he passed 27. Despite this he would become a 7-time All-Star and win multiple batting titles while slashing .312/.418/.515. A few extra seasons early in his career or a few less injuries would have placed him within sight of 3,000 hits and 400 homeruns.

Four Baseball Blasphemies in Support of Martinez

Four horsemen usher in the apocalypse in the Book of Revelation, and four seemingly baseball-blasphemous statements can be said about Martinez.

Designated Hitters Are Not All Terrible Fielders. While admittedly the weakest point in Martinez’s favor, he was at one time a decent defender. Before he ever made his Mariners debut he led AA-Level Southern League third basemen in fielding and was described as a defensive prospect rather than a potential offensive force. Once installed at third in the majors, he put together excellent performances in 1990 and 1991. He even started a triple play in 1991 against the Texas Rangers. While his more advanced defensive stats show he wasn’t going to go down in history as a great fielder, he did manage to put together a brief but favorable showing in the less precise but traditional metric of fielding percentage (.946, tied with Hall of Fame corner infielder Tony Perez). Martinez’s ability to play the field began to disappear with the progression of an eye condition. Unable to properly focus his right eye, he switched to a full-time designated hitter role in 1994, but not before playing nearly one third of his career as a position player.

Prior to this, baseball card companies took notice of his glove and depicted him fielding on several dozen issues. Upper Deck seemed to prefer photos of Martinez playing defense, even including him in a 2001 Gold Glove-themed insert set. Topps used identical fielding shots in both its Finest and O-Pee-Chee Premier issues of 1993. Donruss tried to show Martinez playing third in 1988 but somehow ended up using a picture of Edwin Nunez instead.

Better Than Ortiz? David Ortiz is frequently introduced as the best DH of all time. Martinez was more valuable. Outside of homeruns, a metric in which Martinez was fairly well versed, he outpaced his Boston rival in almost every category. Their batting averages are separated by 26 points, the same size gulf as seen between Wil Cordero and Barry Bonds. Ortiz has 225 more hits but needed more than 1,400 additional at-bats to collect them. Martinez struck out less often while drawing walks at a higher rate. He garnered more than a dozen WAR above Ortiz while playing way fewer games. Adjusted metrics like wRC+ give him the edge as well. The advantage remains in Martinez’s favor when comparing each players’ best seasons head-to-head.

Better Than Ichiro? Ichiro Suzuki is about as iconic a Seattle Mariner as Ken Griffey, Jr. If you ask a random Seattle fan who their most consistent hitter was, Ichiro is a likely answer with his .311 batting average. Martinez actually has a higher batting average (.312) than Ichiro and carried the same number of batting titles. He also beat’s Ichiro’s slugging percentage (.418 vs .402) thanks to 150 more doubles and almost triple the production of homeruns. Martinez drew twice as many walks as Ichiro and carried a weighted on-base percentage nearly 80 points higher (.405 vs. .326). Martinez generated more WAR than Ichiro despite playing more than half his career as a designated hitter and appearing in 20% fewer games.

Better Than Griffey in Seattle? While my fielding comment is the least sound, the mere suggestion that Griffey isn’t the best Mariner hitter of all time is sure to generate angry murmurs from the Seattle faithful. Griffey was clearly at his best in Seattle before spending a decade with the Reds (and White Sox) as a shell of his West Coast self. When people talk about Griffey, they are talking about his time with the Mariners. So how did his Seattle stats compare?

| STATS | PA | .AVG | HITS | 2B | HR | K% | wRC+ | wOBA | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ken Griffey, Jr. | 7,250 | .292 | 1,843 | 341 | 417 | 14.9% | 139 | .394 | 67.6 |

| Edgar Martinez | 8,672 | .312 | 2,247 | 514 | 309 | 13.9% | 147 | .405 | 65.5 |

During their tenure in Seattle, Martinez beats Griffey in many metrics. He carries a batting average 20 points higher than the man in the backwards hat. Griffey hits homeruns about a third more often as Martinez but the latter more than makes up for it with fewer strikeouts and a barrage of doubles. Martinez delivers more valuable hitting, generating wOBA scores more than 10 points higher than Griffey. His on base percentage of .418 is 44 points above Griffey’s .374 and ahead fellow Donora, PA legend Stan Musial. His wRC+ of 147 is not only better than Griffey’s 139 during this period; it is tied with the likes of Mike Schmidt and Honus Wagner. Griffey edges Martinez by the slimmest margin in terms of WAR, though it should be remembered that Griffey’s stats include a significant defensive contribution from playing the outfield while Martinez accumulated his stats almost entirely with the bat. In short, Martinez makes a case for having averaged a better career than the Seattle-only version of Griffey.