Today’s story begins with an umpire’s misplaced protective equipment at a 1987 Cubs game. The April 17 contest was late in starting after plate umpire Eric Gregg was unable to locate his armor that was so necessary to life behind the plate. Not exactly a slender reed of a man, having once been fined $5,000 for exceeding a 300 lb. National League umpire weight limit, Gregg was at a loss to find shin guards and padding that would fit. The depths of Wrigley Field were turned upside down in a game-delaying search for large size gear. After about half an hour the missing umpire emerged in a cobbled together mix of blue Chicago paraphernalia and the rigging of the Cubs’ backup catcher.

This would ordinarily not be an issue for the regularly scheduled broadcast, as popular announcer Haray Caray would have easily found ways to entertain the 23,000 fans and many more following the game on WGN’s television broadcast. However, Caray was recovering from a stroke and left the broadcasting duties to former pitcher Steve Stone. Cubs fandom provides a deep bench from which to draw partisan commentors and viewers of the opening of this particular broadcast were greeted by Stone and a substitute filling in for Caray.

That sub was none other than comedian Bill Murray, and the comedian’s improv experience proved its worth as the delay dragged on. After some initial small talk and Murray’s descriptions of various people in and around the ballpark, the duo began to get down to business. Murray read the starting lineups for each team, taking special care to provide his own version of a scouting report on each of the visiting Montreal Expos.

A rather intense sports fan, Murray was familiar with many of the names taking the field that day. He did however, trip over the name of Montreal first baseman Andres Galarraga (see the 4:50 and 11:55 timestamps in the above video). There are a lot of letters floating around in that Venezuelan name, and Murray seemed to bump into each one. Even my spellcheck is screaming at me as I type this.

A Random Name to Remember

Step away with me from baseball for a moment as I flail around trying to obliquely tie some random trivia to this story.

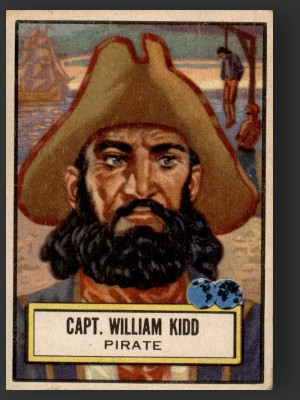

The complexity of pronouncing words has long had an outsized effect on people’s actions. Restaurants specializing in foreign food have realized simplified names and numerical order systems result in larger sales over the outcome of patrons trying to uncertainly pronounce the name of an unfamiliar dish. Take the example of William Kidd, who apart from having a spare “d” in his surname is generally considered to have given little trouble to those trying to record his name. Today he is more popularly known as Captain Kidd. His easy to pronounce name may have made him a bit too memorable, leading to his conviction and subsequent hanging for piracy in 1701.

Kidd vigorously disputed these allegations. He had left London not as a pirate, but rather as a hunter of pirates (and the French). He had the backing of King William III, multiple high ranking lords, and the governor of New York. Authorized to plunder and make prizes of enemy vessels, he captured a small French ship on his way to New York. An incident at the outset of the voyage saw his ship refuse to salute a British naval vessel, leading to the navy targeting his sailors with press gangs. Faced with a shortage of manpower so early in the voyage, Kidd replaced his newly hollowed-out crew with a problematic assortment of sailors with shady pasts. A second round of impressment nearly followed when his ship was detained by a naval captain demanding Kidd supply him with more than two dozen sailors. Kidd promised the men would be selected and delivered to the waiting ship the next morning before quietly slipping out to sea during the night. From that point onward elements within the Royal Navy would openly call Kidd a pirate, despite his possession of letters or marque exempting his crew from forced naval service.

Success beyond the early French prize proved elusive for much of the multiyear trip. Several times he held back the crew from attacking ships that were deemed to be friendly to England, orders that infuriated a semi-piratical company that was essentially paid on commission for whatever they captured. Kidd’s boat was active in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea, regions in which his conversations with passing captains and rumors from the British Navy made his name well known. “Kidd” was easy for tongues of all nations to remember, much more so than multisyllable names with spellings that shifted with each new alphabet encountered at the mouth of the Indian Ocean.

Kidd eventually landed his big prize, capturing the richly loaded Quedagh Merchant. The capture was a tangled mess of admiralty rules, involving a four hour chase, different people pretending to be captain of the prize ship, false identification papers for the vessel, false colors on Kidd’s ship, and a multinational group of owners who would demand answers for their missing goods. Basically Kidd captured a friendly ship in a move made techincally legal by the way in which the target presented its documentation. It was in keeping with the letter of the law but far from the spirit. Knowing that his crew would almost certainly mutiny if he returned Quedagh Merchant to its commander, Kidd took the ship and turned homeward.

The return trip was highly problematic. Dutch ships affiliated with the missing vessel began hunting Kidd. Unhappy with his leadership and not wanting to share the loot with the enterprise’s financial backers, more than 80% of the crew mutinied, taking the majority of what had been captured with them and joining forces with the pirate Robert Culliford. Kidd returned to the Caribbean with a skeleton crew and a pair of ships that had been nearly stripped of all essentials. Many of the backers of the Quedagh Merchant held significant political sway and pressed their case to the highest levels of government in India and England. Receiving word that most now considered him a pirate, he returned to New York in hopes of clearing his name through the governor that had helped send him on his voyage.

Instead, Governor Bellomont had Kidd arrested and returned to London to face trial. Strings were pulled, leading to the “misplacement” of the false identification documents provided by the Quedagh Merchant. Funds for his defense were withheld until just days before his trial and he did not meet with legal counsel until less than 24 hours remained. Witnesses from other ships gave their accounts of what they saw, and even more testimony about what they heard about Kidd with his easy to pronounce name padding his alleged criminal resume.

Thanks for taking that historical tangent with me. I think I really just wanted to talk about pirates today.

Andrés

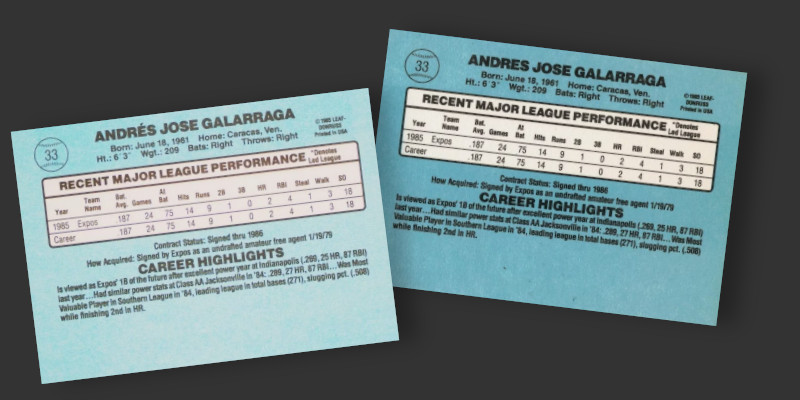

Captain Kidd might have gone down the way he did in history in part to an easy to pronounce name. Andres Galarraga’s name, however, caused issues from the very beginning. His first MLB baseball card appearance came as a Rated Rookie in the 1986 Donruss set. The card can be found in two varieties as Donruss could not figure out whether or not the back of the card warranted an accent mark over his first name.

Use of the accent mark was determined to be the correct way to spell his name. Donruss made the correction and ensured its end of season Rookies release and the Canadian Leaf brand all featured the correct spelling. The card manufacturer took it one step further in 1987, opting to include an accent mark on Andrés as well as his middle name José.

Galarraga’s rookie cards and their variations caused a bit of a stir at the time of their release. The Readers Write section of a Beckett Baseball Card Monthly from the era refers to his cards as one of the “hot rookies” of 1986 alongside Wally Joyner and Jose Canseco. Good company as far as prospecting goes.

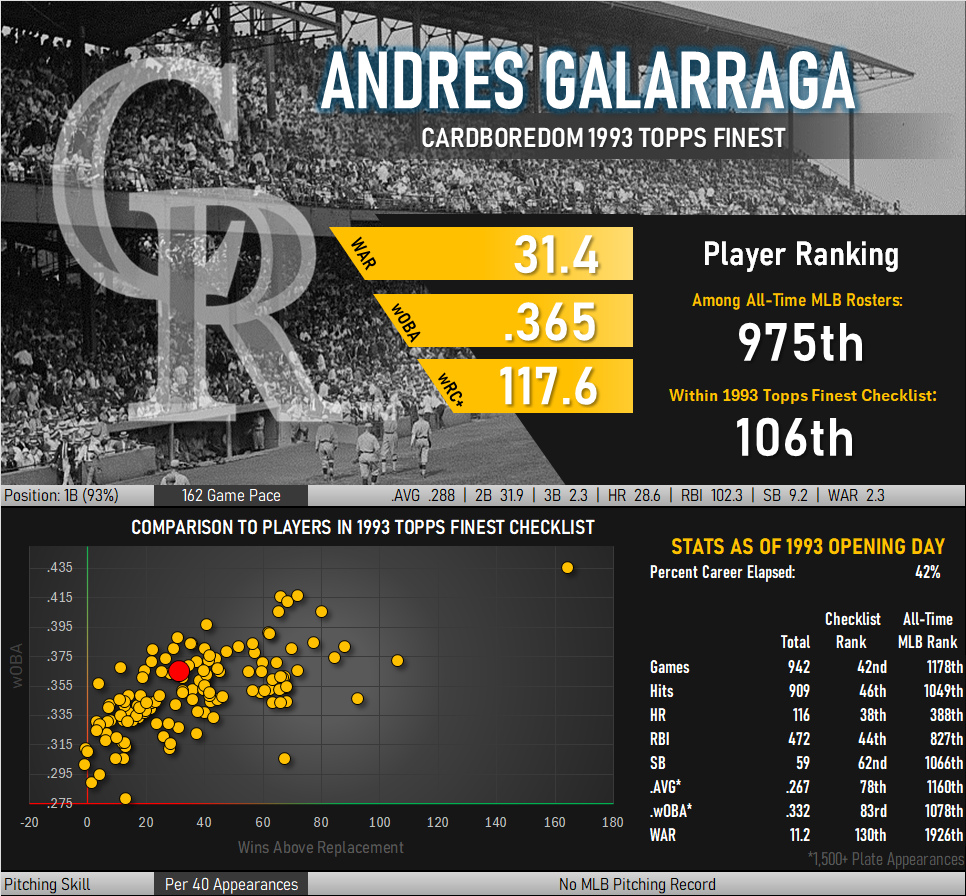

By the time I started collecting his cardboard beyond 1986 was no longer much of force. He was fast approaching 30 years old and had yet to really put his potential together into more than one outstanding season. The March 1993 edition of Beckett reported only modest interest in his rookie cards and omitted him entirely from any individual card pricing for any set beyond 1986. Keep in mind that this was an era in which the publisher thought it best to individually report high and low prices for 112 different base cards from the 1991 Fleer set. At Opening Day of the 1993 season Galarraga had played in nearly 1,000 games, had a .267 career batting average, and was moving to his third team inside of 3 seasons.

¡Andrés!

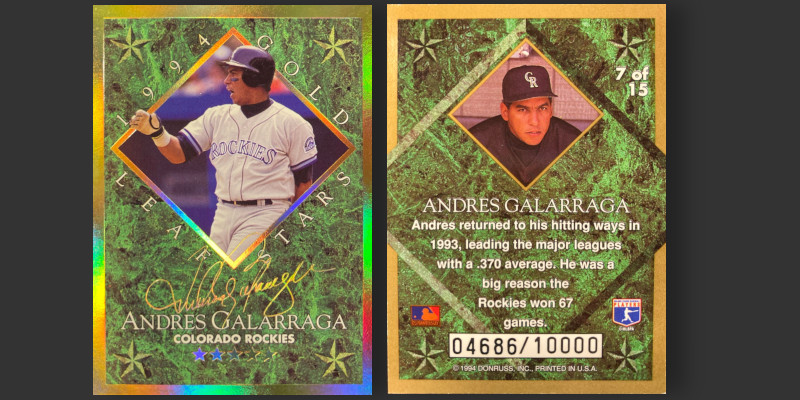

While Galarraga would eventually wear four more home uniforms, that third team would prove pivotal in defining his career. Galarraga was an early member of the Colorado Rockies, joining the club via free agency before the expansion draft took place. He made the signing decision look good by immediately winning the batting title after flirting with the .400 mark for much of the season.

This was such an interesting stat for so many reasons. His .370 batting average was the highest since Tony Gwynn produced a matching total in 1987. While Gwynn and others had made legitimate runs at hitting .400, they had the advantage of first base being ~ 6½ feet closer by virtue of batting left-handed. The right-handed Galarraga’s .370 mark had not been touched by an AL/NL righty since Joe DiMaggio in 1939. The ensuing three decades have only seen Nomar Garciaparra added to the very short list of high average righties.

You would think that such a high batting average from a power hitter would place Galarraga at the top of on-base metrics as well. Despite slugging .602 and leading the National League by a dozen batting points, he ranked 14th in on-base percentage. That is a nearly 200-point differential between his OBP and slugging. That’s what drawing just 24 walks (half of which were intentional) in a season will do to your stats.

High averages typically correlate with an eye for the strike zone. That was not the case for Galarraga. He struck out almost four times as often as taking a base on balls, a ratio that would be even higher had his career tally of intentional walks not hit triple digits. When he retired in 2004 his 2,003 career strikeouts ranked second in the history of the game.

Despite this, Galarraga is remembered as a power guy rather than a contact hitter. The season in which he batted about as high as Ichiro Suzuki’s best season was accompanied by two dozen homeruns. He has a career triple crown to his credit, having led the league in batting average, HRs, and RBIs at various points while also capturing multiple gold glove awards. He slugged 399 career HRs, more than 300 of which came after age 30. That total could have been much higher had he not missed more than a year battling cancer, having averaged 44 dingers over the previous three seasons.

Topps Finest

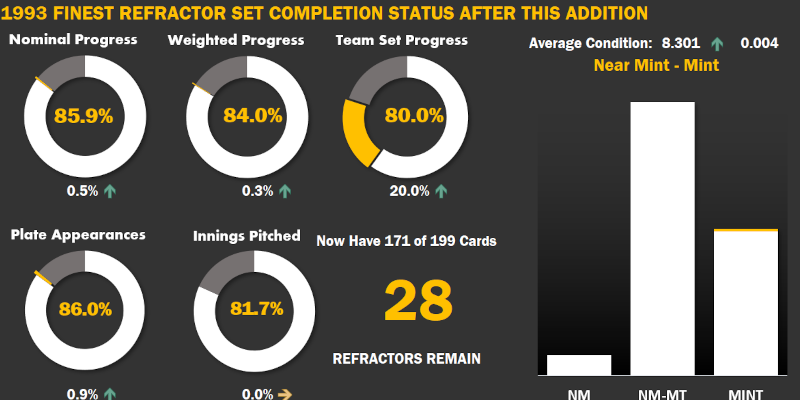

Galarraga is one of four Colorado Rockies appearing in the debut of Topps Finest, a set intended to highlight the very best ballplayers of the era. Collectors had largely abandoned him at this point, but Topps made sure to remember his name when it came time to predict who the top Rockies would be.

As a newly formed team, the Rockies had little in the way of game action photographs to offer to card manufacturers. Topps acquired many of the photos used in the ’93 Finest set at that year’s spring training games. Backgrounds were removed for the images used on the front of cards while they remained in place on the back. Sparse groups of spectators, if any at all, can be seen in some of these shots. Galarraga’s card depicts the packed audiences of the Rockies’ Cactus League games. Colorado would go on that year to set the MLB season attendance record with more than 4.4 million tickets sold (more than the five times what Oakland sold in 2023).

That’s a lot of fans that won’t soon forget Andres Galarraga’s name.

Trivia: “Galarraga” has just as many letters as his nickname, “The Big Cat”