There’s a favorite stat that gets passed around whenever Mariano Rivera is discussed: More people have walked on the moon than scored against him in 16 years of postseason play. Taking the story further, fewer players homered off of Rivera in the postseason than travelled with the Apollo 11 spacecraft in the first lunar mission. Neil Armstrong became the first to touch the lunar surface, and Cleveland Indians catcher Sandy Alomar, Jr. became the first to touch Rivera for a postseason homerun in 1997.

The Part Time Full Time Catcher

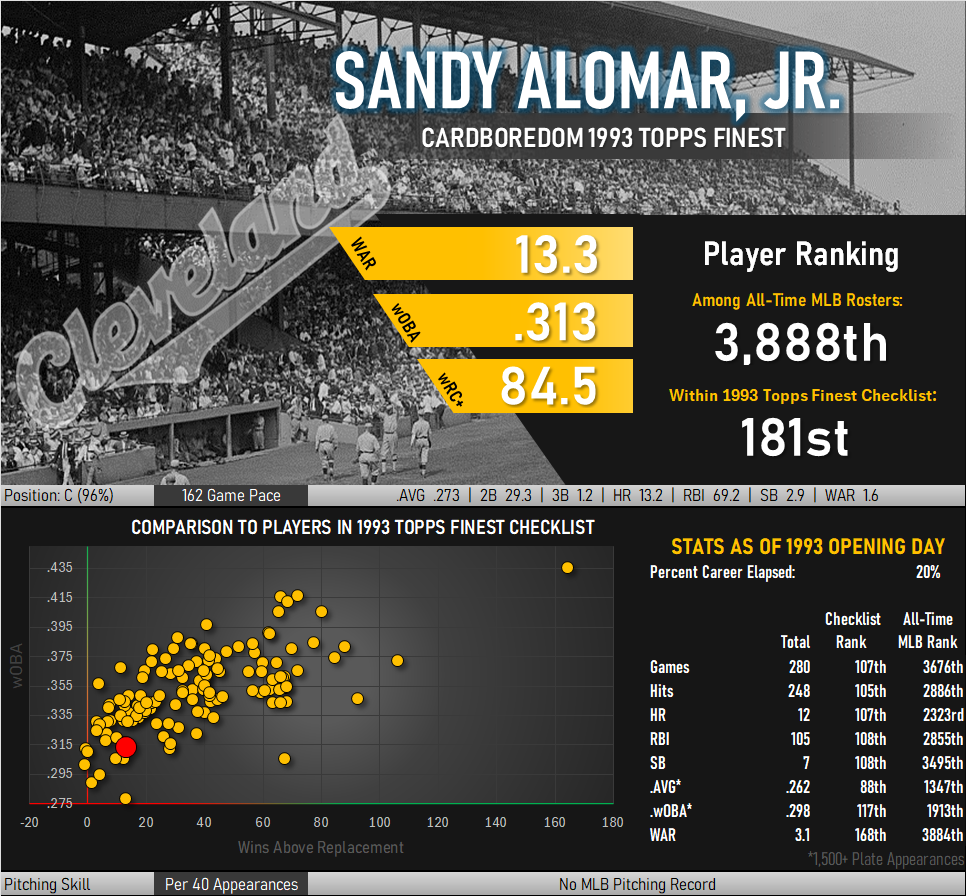

Alomar’s career peaked in that moment, capping a 1997 season that was easily the best of his 20-year career. His first taste of the big leagues came a decade earlier in 1988 when he struck out in his only plate appearance (don’t worry, he got better). A catching prospect stuck behind Benny Santiago in San Diego, Alomar only came to bat 22 times the following year and was traded to the Cleveland Indians alongside Carlos Baerga for Joe Carter.

Alomar broke out in Cleveland, winning American League Rookie of the Year honors while batting .290 and delivering impressive defense. He played in 132 games in that 1990 campaign, a mark that would unfortunately be a career high. Alomar was frequently injured, relegating the undisputed starting catcher of the talented ’90s-era Indians to part-time status. For the rest of his tenure in Cleveland (1991-2000) he played in just 853 of 1,620 potential games. By age 30 he had logged fewer than 500 games. Ticketholders during the decade essentially had even odds of seeing Alomar make an appearance.

The Fans Still Loved Him in Cleveland

Cleveland baseball fans had rediscovered their team in the early 1990s. The previous decade had been so bad that the Indians had been the subject of Major League, a comedy about the worst team in baseball overcoming an owner bent on sabotaging all chances of winning. That changed with the arrival of Alomar, his traded teammate Baerga, and sluggers Albert Belle and Jim Thome.

Alomar made six All-Star teams with Cleveland, amazingly doing so whenever his performance was suffering. His second appearance came as a starter in 1991 when he was batting .217 and posting negative WAR in 1991 for the 57-105 Indians. He was again named the AL starting catcher in 1992, a year in which he generated 26 RBIs and just 18 extra-base hits. Despite this, Alomar generated so much enthusiasm from Cleveland voters that his vote totals surpassed AL catching mainstays like Mickey Tettleton on a regular basis.

Alomar has appeared as a potential manager for several professional teams. The sport likely hasn’t seen the last of Sandy.

Hobby Reception

Even when he was stuck in the San Diego farm system, Alomar generated some hobby buzz. The April 1989 edition of Beckett Baseball Card Monthly shows his 1989 Donruss Rated Rookie card changing hands on equal footing with the set’s Griffey rookie. Once he got more than just a handful of appearances under his belt in mid-1990 his rookie cards continued to trade on an equal basis with those of his brother, Roberto, and Gary Sheffield.

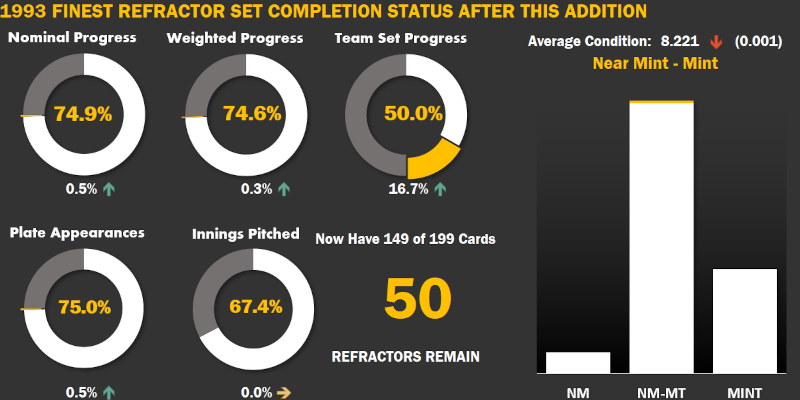

The injuries that curtailed his playing time eventually began to weigh on collector enthusiasm for his cards. By the time Topps rolled out the Finest product in 1993 any non-rookie Alomar cards were considered commons. His once-popular rookie cards still garnered a passing interest but were essentially gone from most collector’s want lists. Alomar’s ’93 Finest refractor remains one of his tougher cards to locate and is one of ten cards accorded a higher weight in Alomar master checklists.

Today his cards from any season can be found in common bins. Those ubiquitous cardboard boxes contain a wide range of players, from those that only played a handful of innings to 20-year veterans that just didn’t escape the gravitational pull of such a long career. Alomar was one of the latter, the kind of player that can elicit a smile from those that remember moments like his game-winning homerun against Rivera.