Two things are true if you remember opening packs of 1952 Topps. One: You’re getting old as dirt. Two: You were looking for pitchers who won 20 games.

Baseball works as a sport because it is so balanced between offense and defense. Hitting a baseball is insanely difficult, and when contact is made the batter is outnumbered by 9:1 on the field. Yet, despite this, a typical game sees both sides score 4 or 5 times. The greatest teams of all time have managed to lose a quarter of their games while the most inept clubs struggle to lose more than a third of their contests. Finding a pitcher who can magically keep hitters at bay is difficult, and coupled with the randomness of the game and the necessity of resting sore arms between starts makes amassing 20 wins a tall order. It’s a nice round number that communicates success without diving into all the details of how a pitcher contributed to the team’s record.

There are 164 pitchers in the 1952 Topps checklist, plus a few more position players who mopped up the occasional inning or later converted to limited pitching duties. Of these, 33 became an “ace”—a 20-game winner—at some point in their careers. 22 had already reached the 20-game mark by the time their cards went to press, while three more added their names to the list as the 1952 season unfolded. These were the pitchers you wanted to come packaged with your bubble gum. Everyone else was an also-ran.

20 Game Winners Appearing in 1952 Topps Checklist

| EXISTING 20 GAME WINNERS | NEW 20 GAME WINNERS (1952) | FUTURE 20 GAME WINNERS |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Bearden | Allie Reynolds | John Antonelli |

| Ewell Blackwell | Bobby Shantz | Bob Friend |

| Ralph Branca | Early Wynn | Billy Hoeft |

| Harry Brecheen | Sam Jones | |

| Murry Dickson | Vern Law | |

| Bob Feller | Billy Pierce | |

| Mike Garcia | Bob Porterfield | |

| Ned Garver | Virgil Trucks | |

| Larry Jansen | ||

| Alex Kellner | ||

| Ellis Kinder | ||

| Bob Lemon | ||

| Dutch Leonard | ||

| Eddie Lopat | ||

| Mel Parnell | ||

| Howie Pollet | ||

| Robin Roberts | ||

| Preacher Roe | ||

| Johnny Sain | ||

| Warren Spahn | ||

| Dizzy Trout | ||

| Jim Turner (Coach) |

Aside from lifting your favorite club 20 games higher in the standings, what was so remarkable about that figure? 20 Victories is a big, round number that is easy to remember. It implied winning at least half the games pitched in an era of 154 game schedules and four man rotations.

Having a 20-win pitcher also seemed to be a necessity for winning the overall season. Every preceding World Series had featured at least one 20 game winner. Seven out of every eight teams participating in these games, regardless of outcome, had one or more 20 game winners on staff. Finding at least one pitching ace for your team seemed to be a prerequisite for admission to October baseball. Without one, there was no hope.

Hope in Philly

Philadelphia is known as the City of Brotherly Love and fittingly had a case of sibling rivalry between the teams forced to share Shibe Park. In one corner stood the Philadelphia Phillies, long underdogs of the National League, more familiar with the cellar than the spotlight. But in 1950, against all odds and thanks to an unexpected surge in pitching prowess, the Phillies pulled off a stunning run to the World Series. Their “Whiz Kids” lineup lit a spark under a weary fan base that had grown accustomed to disappointment, suddenly breathing life into a city that hadn’t seen a World Series title since the onset of the Great Depression.

Across the diamond, and the previous owner of that championship title, stood the Philadelphia Athletics—at one point the pride of Connie Mack and the American League. By 1950, however, their luster had faded. Though they boasted a rich history of World Series appearances, the team was mired in a stretch of mediocrity and mounting financial hardship. Despite owning Shibe Park, the Athletics had become landlords of a losing legacy. With attendance in steady decline and debt piling high, memories of Lefty Grove, Jimmy Foxx, and Mickey Cochrane leading victory parades were fading. In a story that has since echoed in time, the A’s were facing homelessness.

The unlikely ascension of the Phillies collided with a flicker of resurgence from the Athletics in the form of Alex Kellner, a 20-game winner who offered a glimmer of hope. For a brief, tantalizing moment, Philadelphia dared to dream: what if both teams could be winners? What if Shibe Park could once again roar with triumph from both sides of the dugout? The promise of simultaneous success opened the door to an interesting possibility: A “home team” World Series where both sides of the battle lines could claim home field advantage.

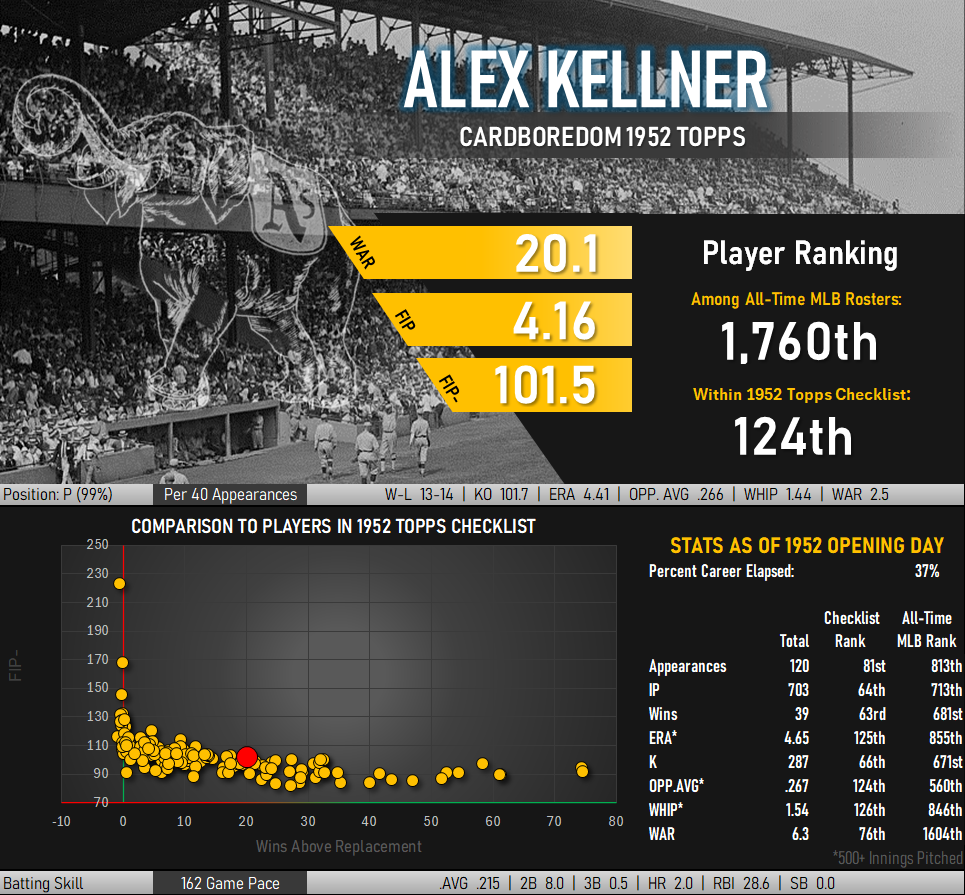

Before the dwindling number of A’s fans could realistically hope to get to the World Series, they needed an ace to carry the team. Rookie Alex Kellner was named to the starting rotation at the beginning of the 1949 season and promptly became an All-Star with a 20-12 record and 19 complete games.

Baseball fans buying packs of cards wanted to find aces behind their sticks of bubble gum. A’s fans wanted nothing more than Alex Kellner, who represented the hope that things would get better. As the 1952 season wore on, a second ace emerged in the form of Bobby Shantz to keep that hope alive. There’s always hope in an A’s fan’s heart, however misguided it may be.

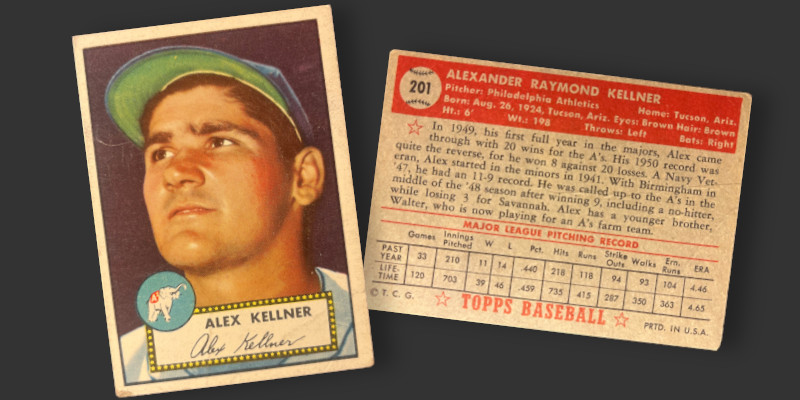

I never noticed it until now, but my ’52 Topps Alex Kellner card has a black background. You don’t see that often in this checklist. Could it be an early card featuring a night game? I doubt it given the shadows appearing on Kellner’s jersey, but then again, that uniform could very well be a ficticious touch up applied to a minor league image. What is for certain is that Alex has a great hairline peeking out from under that A’s cap.

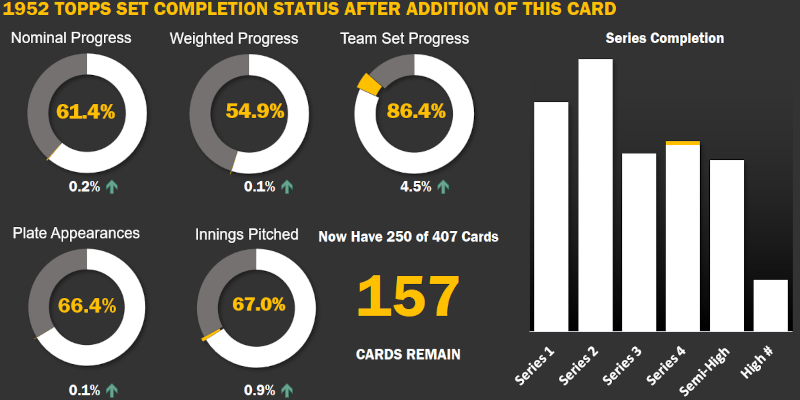

This is my 250th unique card from the 1952 Topps set and takes me tantalizingly close to 90% completion of the Philadelphia A’s team set (3 cards to go). The overall condition is pretty nice, brought down by an out of the way crease in the lower right corner. Kellner looking towards the upper left draws your eye away from it, helping this card more than others with similar wear.

The text on the back mentions Alex’s brother Walt, who would end up making his MLB debut with the A’s near the end of the 1952 season. Walt posted only 7 innings in the big leagues and had zero baseball cards (MLB or otherwise) issued during his lifetime.