Fish Man Good. If it’s 2024 and you say that phrase people immediately know you’re talking about the Angels’ Mike Trout and cannot help but agree. With the possibility of seeing his 400th career home run this year, there will be a lot of people talking up “The Fish Man.”

Mike Trout may be the best player named after a fish, but that has not always been the case in baseball. Dizzy Trout put together a borderline Hall of Fame career in the 1940s. His son Steve Trout played for about a decade in Chicago. Catfish Hunter made it to the Hall, Mudcat Grant made a name for himself, and Catfish Metkovich was just happy to play ball. Kevin Bass led a hole school of players with the same last name. The sport has seen players named Carp, Herring, Pike, Haddock, Ray, Whiting, and Pollock. First names have also proven good areas to cast about for fish puns. Marlin Stuart, Cod Meyers, and Shad Williams all likely heard their share of fish jokes.

Behind (Mike) Trout, there is one player that almost universally comes to mind when discussing players with aquatic names. Tim Salmon.

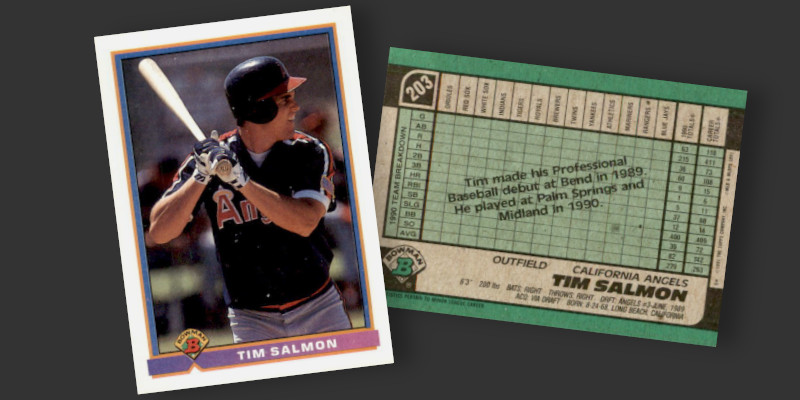

The Angels’ original “Fish Man” was indeed good. He averaged almost 30 HR/162 games. His .385 career on base percentage ranks is equal to Tim Raines and is higher than Willie Mays. He holds the career mark for walks by an Angel. His 130 WRc+ is on par with Carl Yastrzemski and John Olerud. Among modern players his overall offensive contribution is equal to Vlad Guerrero, Jr. and Jose Altuve. Fish. Man. Good.

To my immense frustration when playing Immaculate Grid, Tim Salmon never once made an All-Star team. He holds the second highest career WAR of any post-WW2 player (behind Tony Phillips) to never represent his league in the midsummer game.

A Close Call in the Water

Playing in the water seems like a natural calling for a guy named Salmon. Indeed, the entire Salmon household has made it an annual tradition to take time off and spend part of their summer cruising around Lake Powell where the Colorado River crosses between Arizona and Utah. They have a timeshare in an absolutely massive multistory houseboat and use it as their base of operations.

This summer the family was in their usual place on the lake when one of the region’s monsoons kicked up. Some of the craft’s lines came out of position and everyone leaped into action. One of the anchor lines that prevent the boat from drifting into canyon walls had become caught under the family’s wakeboard boat and Tim tried to adjust the line. Between the movement of the boat, extreme wind, and a motorized wench the line had built up tremendous tension. When the forces reversed it snapped upward, fracturing Tim’s wrist and sending him flying into the boat tethered next to him.

The accident went about as well as it could have. He was quickly transported to a hospital in Page, Arizona and should just about be fully recovered at this point. If the line had caught his head, sent him into the water, or both, this very well could have been a memoriam post.

The Great Rookie Card Shift

Salmon’s first appearance in a major baseball card release came in 1991. That season’s cards looked to be filled with a lot of the homogeneity that had marked much of the previous five years of junk wax: Cards were overproduced. Checklists regularly approached 800 cards. Designs were generally uninspired and inserts had not yet changed the hobby to the degree they would in a just a couple years. Then, almost imperceptibly, there was a change.

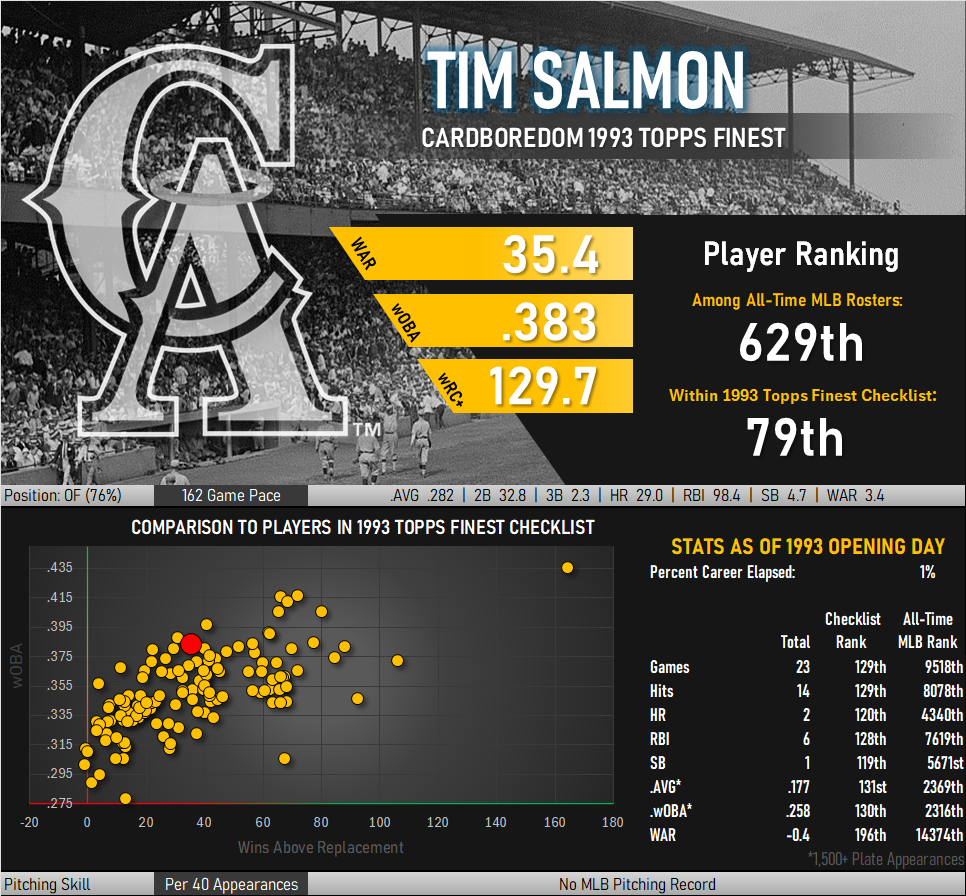

Topps had bought out Bowman, its card producing rival, in the mid-1950s and shut it down. Seeking another line of revenue and hoping to capitalize on brand nostalgia, the Bowman brand was brought out of retirement in 1989. For two years its cards represented a bit of a poor cousin to those produced under the Topps logo. 1991’s edition looked to be more of the same: White bordered cards, minimal design elements, and a team by team breakdown of player performance.

The statistical tables on the back of the cards were mildly interesting, though a surprising number looked like the Tim Salmon card above. Tim, it would seem, had never played in a Major League game. He was part of a crop of more than 150 rookies and prospects comprising more than a fifth of the Bowman checklist. The team putting together Bowman’s 1991 checklist had purposely sought out an above average number of first-time (or no-time) players in order to beat rival card producers.

Bowman had a virtual lock on Salmon rookie cards, being the only mainstream producer to issue his card in an MLB set. Board game maker Classic managed to get a Tim Salmon rookie into the green-bordered travel edition, but that only came as a complete set and even uses the same photo popularized by the Bowman card. With this card and the other 149+ rookies in its checklist, Bowman had taken its first step to truly differentiating its cards from Topps and transforming itself into the place where rookie cards come from. Bowman ran with the idea in 1992, focusing even harder on early rookies (e.g. Mariano Rivera dressed for high school picture day) and significantly shifting card quality towards the modern era.

Bowman’s Salmon card arrived on store shelves in the first months of 1991, despite him not playing a single inning with the Angels in 1990. He didn’t play in 1991. He didn’t even get called up to the big league team until the final weeks of the 1992 season and even then he batted .177. Bowman still included him in the 1992 checklist, Donruss put him on an insert titled “Rookie Phenoms”, and room was made in the low production year-end update sets from Fleer and Score. This was the period in which manufacturers were falling all over themselves to issue cards of career minor-leaguer Brien Taylor.

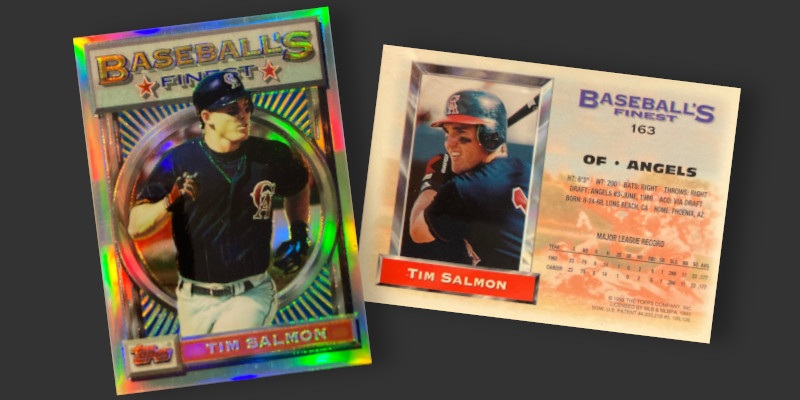

It is against this backdrop of early-’90s rookie card one-upmanship that Topps Finest first appeared. One of the most consistently mentioned drawbacks of the set is a lack of rookie cards. This is in keeping with a small 199-card checklist that claims to only focus on the “finest” baseball players – something that almost by definition excludes rookies. At first glance that looks to be the case with only J.T. Snow and Mike Lansing making their debut. However, when you take a step back it becomes pretty clear that Topps was looking for big name rookies in its ’93 Finest product.

Both winners of the 1993 Rookie of the Year voting appear in the Finest checklist, something collectors shouldn’t expect from a “rookie-free” issue. Neither had appeared in prior year Topps branded offerings with the company going as far as to put Piazza on one of its infamous “floating head” multiplayer rookies in the flagship Topps release. The Finest set included other first-year entrants to the big leagues. Al Martin, Kevin Young, and David Nied each had a dozen or fewer games under their belt prior to 1993.

Without the premature rookie cards and update releases, Tim Salmon’s rookie card could very well have been a ’93 Finest Refractor.

Fun Fact: Price guides at the end of 1993 ranked the Salmon card equal to the set’s Ken Griffey, Jr. refractor.