Two years ago I began trying to track down each of the 1991 Donruss Elite inserts. They were randomly inserted in the first packs of cards I ever opened and still have a pull on collectors of the era more than three decades later. My friends and I bought tons of 1991 Donruss wax packs and never found one, though we all would make up boasts about how we knew a guy who found an Elite (you wouldn’t know him, he goes to another school).

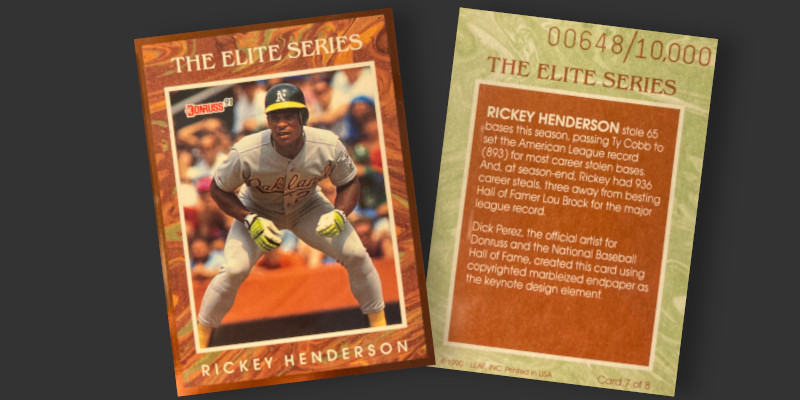

With a print run of 10,000, the Elite cards are certainly not rare. The trick is finding someone willing to part with them. If you pulled one from a pack and still have it, the card is almost a part of your history. Many of the ones that do become available have condition issues.

When I finally found one in an acceptable condition it turned out to be a Rickey Henderson card. It is shown below, bearing the serial number 648 of 10,000. I have heard (not confirmed) that the first 5,000 Elite cards were inserted into first series wax packs with the remaining higher serial numbers filling out the second series.

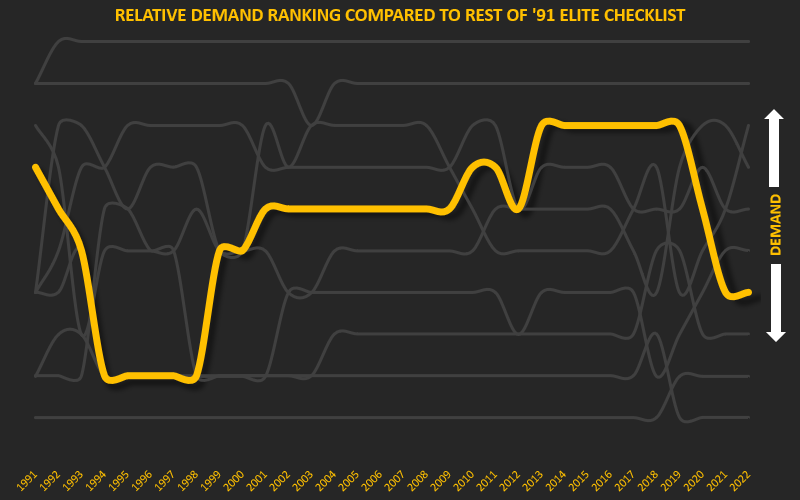

After the initial excitement of pulling an Elite card from a pack, the question that immediately follows is asking which player is pictured. Getting any Elite is cause for celebration, but there is definitely an order of preference for players among collectors. What is interesting is how these preferences changed over the past 30+ years.

The Henderson card is a perfect example of this. Shown below is an illustration of the relative demand for each Elite card over time. Pricing data was collected as a proxy for demand, as supply of each card is a known quantity and collectors effectively voted for their favorites using their wallets. Cards with the highest average secondary market pricing appear at the top of the rankings and those with less demand are at the bottom.

In 1991 Henderson was at the height of his playing popularity, having just ended the 1980s as the decade’s most effective player and beginning the ’91 season with a new all-time stolen base record. Once the record was his, collectors began to move on to newer and shinier things. As a speed guy getting into his 30s, it was assumed his performance would begin to fade away. Henderson’s oversized self-aggrandizing personality worked in his favor when he was the best, but began to work against him when his production began to drop to the level of mere mortals. Other players in the checklist began putting together impressive runs, such as Cecil Fielder and Matt Williams.

Henderson’s Elite cards fell near the bottom of the rankings by the time of the ’94-’95 strike. His relative position began to recover at the end of the decade when it became apparent he had a chance to get to 3,000 hits. It was around this time that the careers of many others in the set were beginning to wind down and the hobby began to reassess where each player was likely to end up among career leaderboards. The release of the Mitchell Report and the results of similar probes in the early 2000s laid waste to the reputations of several members of the checklist but left Henderson’s untouched. The rising popularity of sabermetrics in the ensuing years made Henderson’s accomplishments stand out even more, leading to this card moving from one of the least desired in the set to being one near the top of the demand charts. The last year or so has seen a shift lower, though I consider this attributable to the pandemic era return of collector interest and a related catch-up in prices for the lower ranked cards that are not offered for sale as often. Give it another five years and I fully expect the Henderson card to be back among the set’s key components.

Best (Only) Rickey Henderson Insert I Ever Pulled

I found a lot of Rickey Henderson cards in packs over the years, as there were a lot of years in which Rickey played. What strikes me about this is that I only once found a Henderson themed insert card hiding under one of those wrappers. Peeking out from one of those blue and white pin-striped 1991 Upper Deck High Series bits of foil was a card known as “SP2,” one that captivated the hobby for about a month.

SP2 was the follow-up to SP1, an insert that had appeared in Upper Deck’s low series packs. SP1 pictured Michael Jordan taking batting practice with the Chicago White Sox and was initially seen as a fun novelty of the era’s top basketball top player. The Jordan card would go on to maintain its allure after he made a surprise pivot away from basketball to pursue a baseball career, becoming his de facto rookie card.

The Jordan card had been in demand since its release at the beginning of 1991 and the card’s “SP” prefix only heightened the chase. Beckett Baseball Card Monthly used “SP” to designate cards as being short-printed and therefore difficult to find. Upper Deck told media that Jordans were inserted at a rate of “5-6 per 10,800 card case,” implying they could be found in about 1:3 wax boxes. The cards seem more plentiful than that, though this could be a function of the massive amount of regular cards produced by UD and management’s penchant for running the presses overtime on popular cards as an executive perk.

It is in the reflected light of the Jordan SP1 that I pulled this Rickey Henderson card. Presumably it was printed in the same quantity, though I do not have any data to back that up. What I do know for certain is that SP2 could only be found in Upper Deck’s 1991 high-series packs that contained cards from the year’s full set (#s 1-800) whereas Jordan was found in the low series (#1-700).

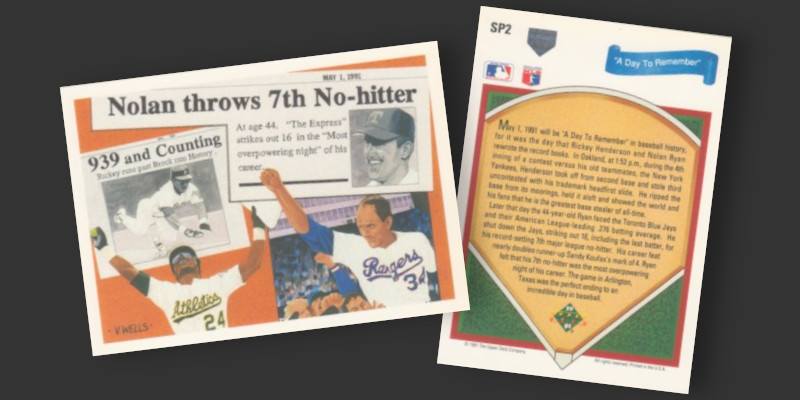

There is no photography. Instead, collectors are greeted with a painting by V. Wells. Wells is familiar to collectors of Upper Deck cards as the artist behind much of the company’s early ’90s team checklists and autographed inserts. The father of Toronto Blue Jays outfielder Vernon Wells (25 career WAR!) and himself nearly a wide receiver with the Kansas City Chiefs, he established himself as the go-to commissioned painter of sports personalities. For decades he worked directly with players looking for portraits, eventually becoming the most commissioned pro-sports artist of all time.

The card commemorates a pair of milestone events that took place on May 1, 1991 and was subsequently issued in Upper Deck’s late-season high series packs. Rickey Henderson is shown celebrating his record stolen base. Baseball had seen the record coming and had prepared for it all winter as he ended 1990 only three shy of Lou Brock’s career total.

Overshadowing Rickey’s stolen base on the card is a headline proclaiming Nolan Ryan’s 7th no-hitter. Ryan didn’t just blow past his own record, he did it unexpectedly at age 44 on the same afternoon as Rickey stealing his 939th base. There is a dichotomy in the card that matched the sport’s general reaction to the two events. Henderson gave an awkwardly worded speech that failed to thread the rhetorical needle between acknowledging he was the new SB leader and honoring those who came before him. He is pictured alone, holding up the stolen base himself. Ryan, on the the other hand, is being carried triumphantly off the field by teammates with a massive crowd cheering in the background. Ryan is waving his cap, thanking everyone around him. His newspaper headline is laid on top of Rickey’s, giving him top billing. Even Nolan’s headline text is bigger.

Frankly, this card was seen by most as a Nolan Ryan card that just happened to include Henderson. This has subsided a bit as time progressed and the oddity of that day’s events and stolen base speech has faded. Both Ryan and Henderson are now viewed as among the sport’s top 0.01%. Sure, I never pulled the Rickey Henderson Elite card from a pack, but I did manage to get this card. Very rarely will you come across a card that features two players of this caliber, and I think it is the 1990s overproduced equivalent to the famous 1958’s Mickey Mantle/Hank Aaron World Series Batting Foes card. I’m glad to have the memory of finding it in the wild.