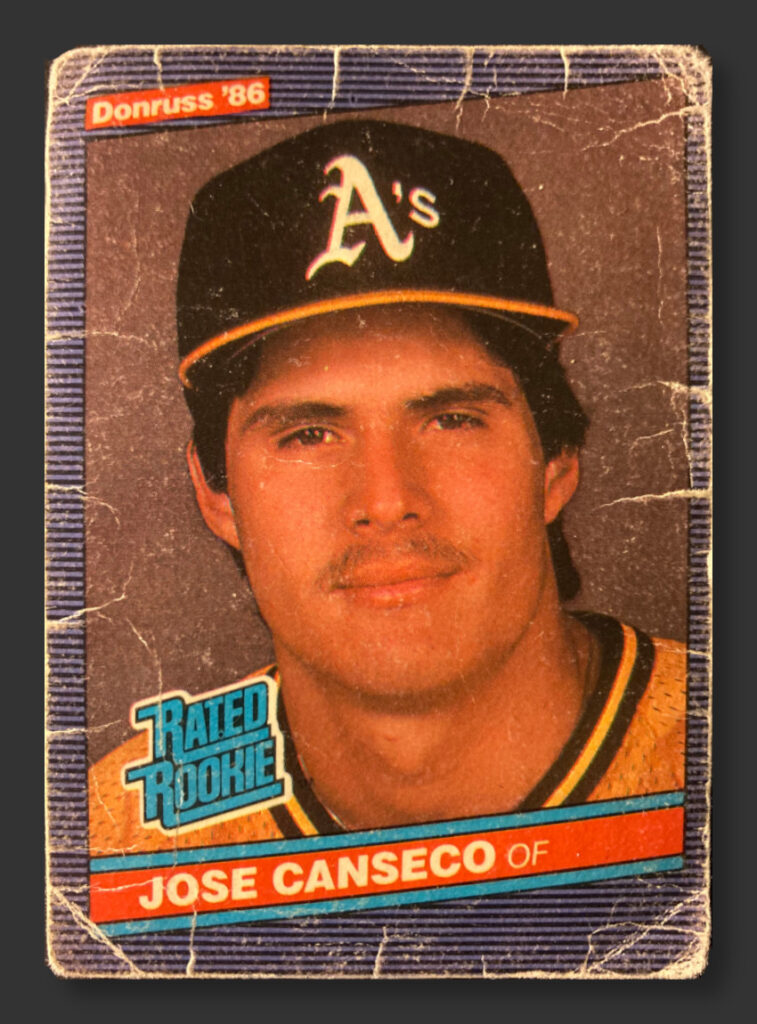

This is a special card, which is probably why it was the first one I selected when I decided to start carrying around old baseball cards in my wallet. The story of my own baseball card collecting history cannot be told without my quest to obtain it, and any collector who was around in the late 1980s/early 1990s has a story to tell about it. It’s a story starter, for sure.

I started collecting cards as a kid on Christmas Day in 1990 (thanks Grandma!) and purchased my first packs the following February. A Jose Canseco All-Star card popped out of that first pack. I wasn’t watching much baseball at the time, as I was too busy playing the sport whenever daylight was touching our backyard. Canseco’s name was the only one I recognized in the pack and he subsequently became my favorite player. When new kids and I would meet to trade cards, the question of who my favorite player was would inevitably be followed by an inquiry of whether or not I had the card.

No further explanation was needed as to which piece of cardboard the question referenced. The Canseco rookie card that was so often the topic of discussion was the one with the big blue logo coming out of packs of the 1986 edition of Donruss baseball cards. It was the best card a kid my age could conceivably have at that time, a card made magical in that adults would willingly hand over a fortune of as much as $100 to obtain. Nobody I knew owned a copy, though many would brag that they “had a friend who owned one,” usually followed up with a response to further questioning with something like “You wouldn’t know him. He goes to another school.”

Never mind the fact that my friends and I all went to the same school and had no way of finding other kids. The myth was as good as truth and that somehow made the card better: It was only 5 years old and already had legends attached to it. A kid with that card had instant credibility with even well established collectors.

Decades later the card seems to have a strong nostalgia factor for people who collected in the late ’80s/early ’90s and just as many legends as it ever did. The card is often described in terms of how insanely pricey it was, though a trip through the pages of old price guides and memories of the era’s card shows reveal that the card was only stratospheric for a few short years (1990-1992). What happened? Why did this card eclipse so many other classic cards? Why the fall? Importantly, why is it in my collection today?

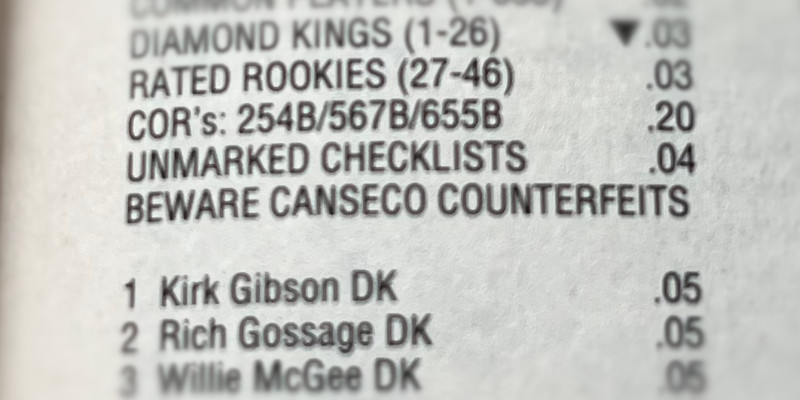

Turning the Rated Rookie Logo Into an Icon

The 1980s were a time of seismic shifts in the niche world of baseball cards. The decade led off with a court decision that broke apart an effective monopoly on card production and introduced collectors to regular releases from the likes of Donruss and Fleer. This increased production was not met with declining sales, but rather seemed to jolt an already growing market into overdrive. Increased demand against a slower climb in supply produced rising prices for cards already in collectors hands. Rising prices themselves seemed to attract newcomers to the hobby and for once current year cards appeared to have some sort of market demand. Largely ignored until this period, rookie cards and the search for the next big name became a driving force in how buyers approached building their collections. The 1980s were the decade of the rookie card.

Donruss had turned in solid, if uninspiring, efforts in its first three years of baseball card production. The firm reset expectations in 1984 with its first eye catching design and print runs more in line with demand with the third place card manufacturer’s products. The firm’s Diamond Kings subset had been the one popular part of its card issues with collectors enjoying newly commissioned artwork from Dick Perez on 26 cards each year.

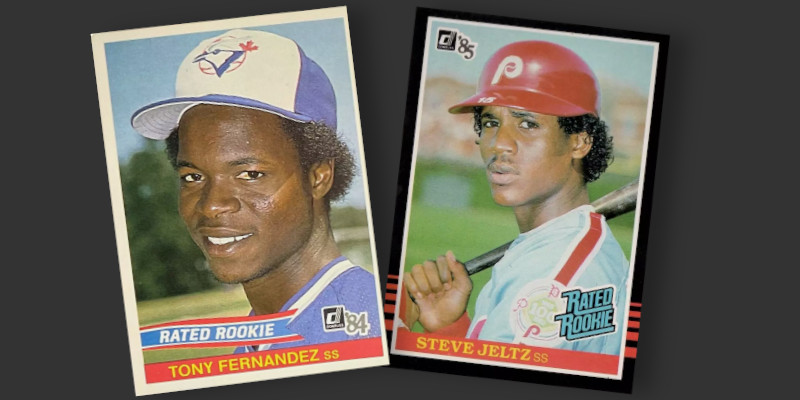

Seeing a winner with Diamond Kings and the rising popularity of rookie cards, Donruss’ design team introduced a new subset for the 1984 season. Entitled Rated Rookies, these cards featured 20 players identified by New York Daily News sports writer Bill Madden. His selections were designed to reflect the new players with the best chance of making an impact on their major league clubs. The cards were flagged with the words “Rated Rookie” to differentiate them from the rest of the checklist. The cards proved popular and the arrangement was extended to future years, along with an expansion of the number of rookies per year to 26 (one for each team). The sophomore edition of Rated Rookies incorporated a new logo, one that would go on to be used for years in future releases.

Madden’s selections were pretty good, though they were overshadowed by something else: Donruss’ checklist managed to capture some of the biggest rookies in the sport without them making the Rated Rookie list. By 1985 Don Mattingly’s ’84 Donruss rookie card (sans RR logo) was the biggest modern card in the hobby. Perhaps bound by his own internal definition of who qualified as a rookie or simply by a lack of foresight, Madden bypassed the likes of Darryl Strawberry, Doc Gooden, Roger Clemens, Kirby Puckett, Eric Davis, and Orel Hershiser, all of whom made their Donruss debut without a Rated Rookie logo. Madden had identified solid players such as Joe Carter and Tony Fernandez, but the star power of the others was on another level.

Madden struck gold in 1986 with one of the best rookie crops in years on tap for the ’86 season. The requirement of one selection per team pushed some names out of contention, relegating players like the Blue Jays’ Cecil Fielder to the regular set in favor of Fred McGriff. With 41 Hrs, 140 RBIs, and a .328 batting average across three levels of play in 1985, Canseco was the obvious representative for the Oakland A’s. Not yet old enough to legally purchase alcohol in California when his picture was taken, Canseco was slotted in as one of the Rated Rookies of 1986.

Amazingly, the other card companies were not lining up to showcase the new face in the lineup. Topps omitted Canseco completely from its 792 card checklist. Fleer frugally squeezed Canseco into a multiplayer card alongside Eric Plunk, labeling the multiplayer card with the alarmingly singular title “Major League Prospect.” At the outset of the year collectors only had two Canseco rookies to chase, and only one looked like a “real” baseball card with the depiction of a single player.

He caught fire that year, hitting 33 home runs and capturing Rookie of the Year honors. At this time Runs Batted In was still held as one of the top offensive metrics to watch and carried significant weight with awards voters. The last time any rookie had led the league in RBIs was Ted Williams in 1939 and Canseco had come tantalizingly close, falling short after a broken finger held him out of a handful of games. His 117 RBIs were the 7th best total for a rookie at that point in baseball history and fell just 4 behind league leader Joe Carter’s 121. Importantly, the leader board’s third place resident was Don Mattingly.

Canseco had surpassed the reigning MVP not only in terms of RBIs, but was threatening to overtake him in cardboard respectability as well. Don Mattingly’s cards were the symbol of all that was in hot in baseball in this era, akin to demand for Shohei Ohtani in terms of today’s landscape. Canseco’s home runs and flamboyant style of play were overtaking Mattingly, who seemed to represent everything associated with old school baseball: Yankee pinstripes. Absurdly high batting average. Team first, personality second. The lack of Topps card and jumbled mess of a multiplayer card from Fleer left Donruss as the preferred choice among collectors that season. Not only had Donruss captured one of the most in demand rookies of the season in its checklist, it had done so with the Rated Rookie logo prominently displayed. The implication was the deep insight provided by Madden on commission to Donruss had given its collectors an edge in finding such a player. Those buying packs of Donruss in 1987 could seemingly expect similar success through deep research.

In hindsight it does indeed look like the Rated Rookies fared pretty well. Many of the best players of the 1990s were given the Rated Rookie treatment. Collectors today still instantly recognize the alliterative subset logo, so much so that Donruss’ successor (Panini) has had success in transitioning the design to some of today’s most popular cards in other sports.

Shown below is a table of the top 10 Rated Rookies in terms of career wins above replacement (WAR). Canseco finished well below these names and smack in the middle of the realm of the “Hall of Very Good” caliber players. Despite this impressive list, if you ask collectors to name a player who appeared as a Rated Rookie I would bet you get more responses of “Canseco” than any of these players who went on to have better careers.

| Player | Rated Rookie Appearance | Career WAR |

|---|---|---|

| Greg Maddux | 1987 | 116.7 |

| Alex Rodriguez | 1995 | 113.6 |

| Randy Johnson | 1989 | 110.5 |

| Chipper Jones | 1993 | 84.6 |

| Ken Griffey, Jr. | 1989 | 77.7 |

| Derek Jeter | 1996 | 73.0 |

| Scott Rolen | 1997 | 69.9 |

| Jim Thome | 1992 | 69.0 |

| Andruw Jones | 1997 | 67.0 |

| Mark McGwire Manny Ramirez | 1987 1994 | 66.3 (tie) |

| Jose Canseco | 1986 | 42.1 |

Portrait of a Solitary Team Player

Like most of the Rated Rookies, Canseco’s card features a portrait rather than an action shot. Many of the rookies were photographed at the edge of training fields and this this is no different. The image used on this card dates back to a Spring Training publicity photo from 1985. Provided by the team to outlets such as The Sporting News, the photograph was likely taken by longtime Oakland Athletics photographer Michael Zagaris. Topps used the same image in the card company’s program for the annual Baseball Achievement Awards banquet, highlighting Canseco as a Player of the Month for May of that year.

One aspect of this image that has elicited decades of comments is Canseco’s terrible mustache. The attempt at facial hair has drawn nearly 40 years of mockery, but its presence on this card reveals something deeper that was at play.

Baseball has long had an odd relationship with facial hair. Prior to the advent of the 1970s the most modern baseball card you would see with a mustache featured a portrait of John Titus. Titus withdrew from Major League Baseball several years prior to the sinking of the Lusitania and by that point it was exceedingly rare to find ballplayers sporting facial hair. Once popular in the mid-19th century, mustaches, beards, and eccentric sideburns spent the latter half of the century becoming associated with outsiders, terrorism, and labor strife. America was tightening its borders and recent arrivals on the inside were doing their best to keep from drawing attention to themselves. Adopting clean shaven looks avoided old-world hairstyles associated with the past and allowed them to visually blend in with everyone else hurrying down busy streets. A series of terror attacks attributed to European anarchists further set popular opinion against anything not appearing homegrown.

Frequent social unrest associated with attempts to organize labor drove additional political division near the turn of the century. Baseball’s dominant organization, the National League, saw the upstart American League rise to challenge its stature amidst a backdrop of repeated attempts to organize players against team owners. The result was a crackdown from ownership that sought to snuff out any hint of insurrection. One of the casualties of this was a near disappearance of facial hair in tightly controlled workforces. World War I and and the Revolutions of 1917 cemented this in popular culture, with veterans eschewing facial hair in favor of properly fitting chemical warfare masks and civilians declining anything associated with the political movement that took Russia away from the Allies.

Political winds began to shift in the 1960s and hirsute styles started to return to the edges of popular culture. A trio of baseball cards in the 1971 Topps set contain hints of mustachioed players, but the sport otherwise looked (on its face) identical to its style of the past 60 years. That changed in 1972 when Oakland Athletics star Reggie Jackson reported to Spring Training with a full mustache and a beard that he had every intention of filling out. Oakland manager Dick Williams informed Jackson that he would need to shave or risk being held out of the lineup. Never easily intimidated, Jackson quickly replied that he was the best player on the team and that it was the sophomore manager who would instead find his position threatened in any such showdown. Williams conferred with team owner Charlie Finley and the pair came up with a novel solution. Not only would Jackson be allowed to play with facial hair, every Oakland Athletic would be required to grow a mustache in order to play that season. Playing a bit on the idea that nobody is special if everybody is special, even Williams would take part in raising his own crop of whiskers.

Last place teams are rarely trendsetters. The newly mustachioed Oakland A’s of 1972 were anything but a last place team, capturing their first World Series title since 1930. They repeated as champs in 1973 and again in 1974, prompting clubhouses around the game to drop prohibitions on facial hair in the process. Oakland, already a center of offbeat culture, became synonymous with mustaches via the likes of Jackson, Rollie Fingers, and Catfish Hunter. These were the guys that a Little Leaguer in Miami grew up watching on television.

Just over a decade later Canseco found himself being invited to the A’s Spring Training facility at Phoenix Municipal Stadium. He had played a couple years of Low A and instructional ball after a 15th round draft selection and had not shown much promise until he put together a decent (but not spectacular) A-level season in 1984. Those early years were rough with more experienced players making fun of the insecure and emotional newcomer. An argument after a rough tag from higher ranked prospect Rob Nelson during this period resulted in management even publicly humiliating Canseco with a temporary demotion to bat boy. That moment sealed any trust he planned to put in teammates and he leaned hard into a solitary, self-proscribed plan for getting to the majors.

His improvement in 1984, however pharmaceutical its origins, was enough to get in front of the big league club for a few weeks in 1985’s Spring Training. Despite the 1980s shift away from facial hair (1982 was the high water mark in terms of percentage of mustachioed MLB players), Oakland’s roster was still majority mustachioed. Prepping for his shot at joining the team, Canseco decided the best way to join the A’s was to look like one. The result was this attempt at a mustache, a lasting tribute to the time Canseco tried to be a team player.

Production and Distribution

As with the 1987 Fleer Barry Bonds I profiled in January, I wish I had a precise answer to just how many ’86 Cansecos exist but have not yet found a satisfactory method for calculating the print run. I still have spotty financial records of card manufacturers and hope to eventually use this data to put together some sort of useful estimate. Time for such a project remains limited but rest assured it remains on my to-do list. If I come up with a plausible number I will be sure to update this section with the results.

My current estimate is that there are somewhere around 800,000 – 1,000,000 of this card in circulation. This estimate is based on the trend of increasing production volume that swept across the hobby in the latter half of the decade, culminating in print runs in the upper single digit millions for the truckloads of cards reaching the market in 1991. Topps was clearly the market leader in the mid-1980s and calculations performed in connection with my research into that year’s Mark McGwire rookie imply a production run of 1.3-1.5 million. Donruss would not yet have matched Topps’ volume the following year, but it would have been well on its way to ramping up towards that number.

Regardless of how many were printed, there are still many unopened Donruss packages out there that could conceivably yield a Canseco or two. Donruss kept its packaging arrangements fairly simple, offering cards in two unopened formats as well as complete sets through hobby dealers at the end of the season. The table below summarizes the ways in which unopened ’86 Donruss material is typically encountered and includes an approximation of the likelihood of finding at least one Canseco rookie. The calculations underpinning these estimates assume each card in a given wax or rack pack is unique, while duplication of cards is possible across multiple packs from the same box. Aside from the stipulation of no duplicates in a pack, cards are assumed to otherwise be inserted randomly with no regard to collation patterns. While Donruss products have been infamous for generating the same sequence of cards multiple times in a box, I have seen enough videos of 1986 box breaks to suspect collation is better than people remember.

| Method | Qty. Cards Included | Note | Odds of Finding at Least One Canseco |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factory Set | 660 | Contains 1 of each card | 100.0% |

| Counter Display | 2,160 | Holds 144 15-card wax packs and 72 Large Packs (obscure oddball issue with no Canseco) | 96.4% |

| Rack Box | 3,240 | Sight unseen – Surface of packs unsearched | 99.4% |

| Rack Box | 3,240 | No Canseco visible on surface of packs | 99.1% |

| Wax Box | 540 | 56.3% | |

| Rack Pack | 45 | Sight Unseen – Marketed as Value Packs | 6.8% |

| Rack Pack | 45 | No Canseco visible on surface of pack – Marketed as Value Packs | 6.4% |

| Wax Pack | 15 | 2.3% |

Profitably Faking a Card

Pulling an in demand rookie card is pretty tough, as evidenced by the odds in the table above. As Canseco’s popularity (infamy?) took off into the 1990s collectors found themselves navigating another challenge: Counterfeits. Baseball cards had transformed from the impoverished step-relation of coin and stamp collecting in the 1950s, to an occasionally pricey niche hobby in the 1970s, and finally into a full fledged battle royale for collector dollars in the late 1980s. The influx of newcomers and their dollars were a siren call to those willing to turn to crime for a quick buck.

By the dawn of the ’90s Canseco’s card had become the most expensive rookie of the 1980s, consistently cracking the $100 mark amid a flurry of demand. This made the card one of the earliest to see widespread counterfeiting, joining the likes of Pete Rose, Don Mattingly, Roger Clemens, Doc Gooden, and Mark McGwire as some of the most frequently faked rookies. Beckett Baseball Card Monthly began regularly posting warnings for many of these cards in 1992, though by this point several years had passed since the fakes began being passed off in 100-count boxes at card shows.

Canseco counterfeits likely began showing up in earnest in 1988, a time when legitimate copies were commanding $40. By this time there were many cards in the hobby that regularly commanded much higher valuations, cards that few would think twice about rigorously checking for authenticity. What made this card such a successful target for reproduction was the sheer volume that could be moved. Vintage rookie cards of Rob Carew, Steve Garvey, and Reggie Jackson all commanded much higher prices but would likely find only a few buyers seeking out these cards. Canseco’s massive popularity and the higher print runs of the era translated into quick turnarounds, enabling fakes to quickly be flipped without drawing much attention to the sudden availability of cards.

The Grading Landscape

I admit it. I have an authentic example of the card but what I really want is to add a gem mint Rated Rookie to my collection. The card in my possession spent an entire year being carried in my wallet and I do not currently have plans to acquire another, so this will have to be a long term goal. The good news is that the card is challenging enough to make hunting down a high grade example entertaining while remaining plentiful enough to provide certainty of eventually finding one that meets my requirements and doesn’t blow a hole in my hobby budget.

Finding an ’86 Canseco is an easy enough task while locating one without flaws is a tougher ask. Never really known for precision and attention to detail, Donruss was cranking out these cards as fast as they could be printed in the mid-’80s. Uneven centering is commonly encountered within this set, particularly from left/right. The dark borders do collectors no favors, as the slightest bit of damage shows as a bright white spot that contrasts with the card’s deep hued edges. This plays out in the numbers reported by the largest grading services, which have collectively rendered opinions on nearly 13,000 examples. 6.3% of these cards were given ratings of 10 out of 10.

[EDITORIAL NOTE: Images to be added shortly….]

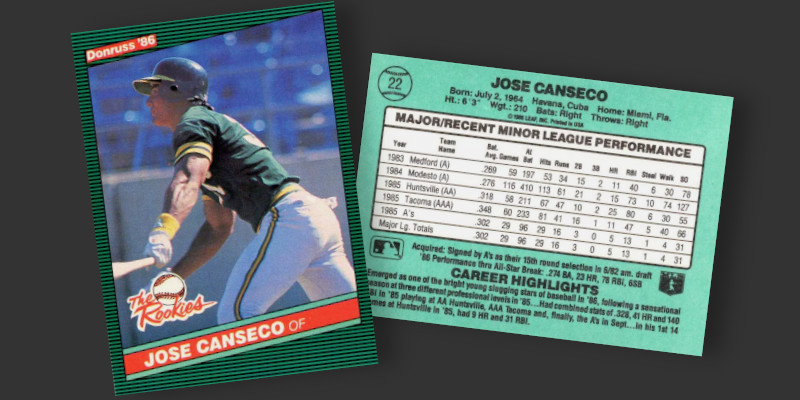

Other ’86 Donruss Canseco Cards

Donruss had a runaway success on its hands in 1986, with collective hobby sentiment favoring its brand for the third year in a row. Hobby shops were regularly filling out bulk order slips to replenish inventory, and the manufacturer obliged with follow-on offerings of several different 56-card boxed sets towards the end of the year. Perhaps the impetus for these cards was as simple as an opportunistic money grab. A more generous interpretation would be the implementation of forward looking strategy to maintain this hard won market position.

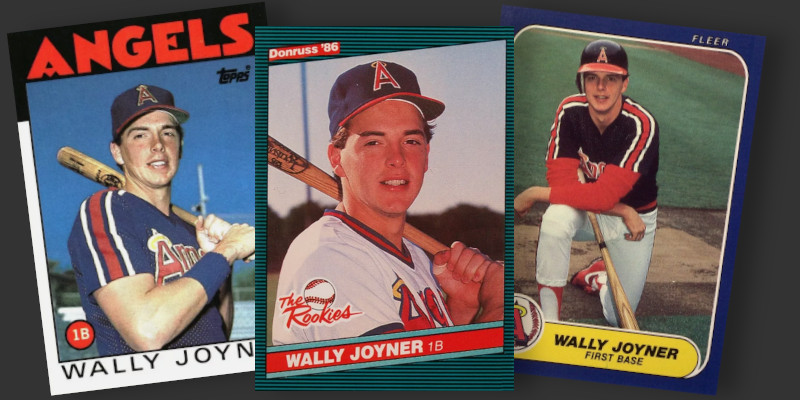

Having the most sought after rookie cards of key players had catapulted Donruss’ standing with collectors. Missing a key newcomer that was picked up by the competition could easily relegate the firm’s cards back to third place in hobby. While sales numbers could induce high fives in the management suite, the knowledge that the checklist had omitted potential Rookie of the Year Wally Joyner had to create a sense that Donruss’ position was not entirely secure.

Joyner was not included in any of the major baseball card releases at the outset of the 1986 season, having not previously cracked the majors and ranking well behind Rob Carew in the Angels’ depth chart at first base. Joyner got his shot when team owners colluded to hold back Carew’s contract. Having never hit more than a dozen home runs in any minor league season, he sent 15 pitches into the stands in his first 36 games. A rookie on pace for nearly 70 home runs in a season gets anyone’s attention and collectors found he was nowhere to be seen among the offerings from Topps, Fleer, and Donruss. Both Topps and Fleer had long established postseason releases that provided collectors with a chance to obtain cards that had been omitted from the regular season checklist. These update sets were certain to have Joyner cards and threatened to leave Donruss shut out until the next year.

The firm’s answer was to launch its own end of year update set. Not only would a Joyner card be featured prominently as card number 1, the checklist would be stocked only with rookies. Highlighting this difference, the new set was marketed as “The Rookies” and featured packaging prominently displaying the word “Rookies” in the largest font. Competitors’ offerings were a mix of mid-season rookie call-ups and cards depicting traded athletes with their new teams. Donruss went right to the heart of why people bought these cards: To get a jump on the rookie cards that traditionally would not have appeared until the next season’s release. Never mind that 1987 baseball cards could be hitting the shelves as early as December 1986. A card with a 1986 design would still be chronologically ahead of the ’87 layout and relegate the latter to second-year status with many collectors.

While the Joyner card was sure to be a hobby success, where were the checklist designers supposed to find so many previously overlooked rookies? Those with excellent on-field performance were obvious candidates and resulted in the inclusion of Barry Bonds, Bobby Bonilla, and Kevin Mitchell. The expansion of rosters to 40 players in September provided collectors with cards of players like Bo Jackson. Still, this only provided a few dozen names, barely enough for a couple packs’ worth of cards and not enough to induce collectors to shell out the $5 or more that this release was expected to retail for.

The checklist creators turned their eyes to the now popular Rated Rookies in the regular ’86 set. After all, if Donruss had successfully scooped the competition with a timely rookie selection it should follow that Topps and Fleer would correct their oversight in their own update issues. Donruss’ The Rookies would be going head to head with these offerings, making an early year success in checklist inclusion a liability if competing issues included these sought after names. The answer, of course, was to include all the rookies that collectors wanted even if they had already appeared in the flagship release at the outset of the season. A majority of the original set’s Rated Rookies were duly pressed into service again to fill out the checklist of The Rookies. Double billing of this nature gave collectors multiple ’86 Donruss cards of Canseco, as well as prominent names such as Todd Worrell, Andres Galarraga, and Cory Snyder. The hard hitting Danny Tartabull is a notable addition given that he appeared in The Rookies in addition to appearing as a Rated Rookie in both the 1985 and 1986 editions of Donruss.

The design of The Rookies differs from regular-issue Donruss cards largely through the use of color. Donruss’ flagship release features borders of narrow blue and black alternating stripes while the end of year release replaces blue with a teal green. In a similar manner the familiar blue background present on the back of the cards is replaced with a mint green hue.

Production lead times necessitated writing up the information for the card backs some time prior to the set’s issuance,resulting in the statistics tables truncating at the end of the 1985 season. The text, however, was written in such a way to give some information about the current year without having to divulge anything specific. The Career Highlights portion of Canseco’s card simply says he “Emerged as one of the bright young slugging stars of baseball in ’86…” Interestingly enough, Donruss saw fit to update the demographic information at the top of the card. Canseco is listed on the back of his Rated Rookie as weighing 185 lbs. while The Rookies has him 25 lbs. heavier at 210.

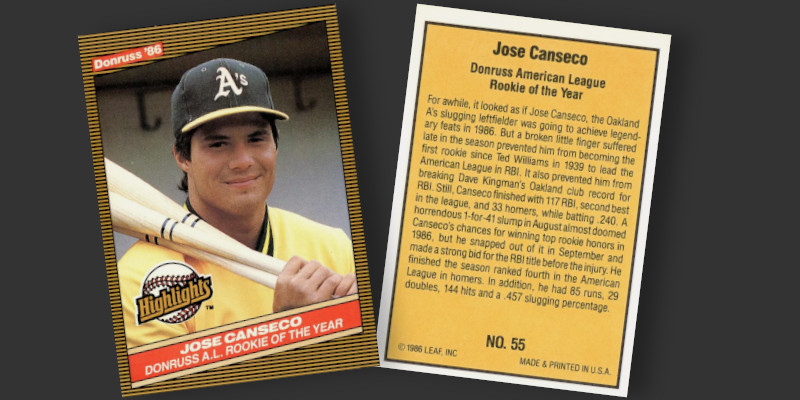

Creating a whole new set out of thin air at the end of a season wasn’t new for the company. The previous year Donruss had released a 56-card boxed set entitled “Highlights” that, as the name suggests, drew attention to specific players and events worthy of mention. The 1985 edition sold better than expected, depleting inventories and ensuring that a high volume follow-on offering would be in the works for 1986.

Donruss released the ’86 edition in November, following on the heels of the release of The Rookies. The cards featured yellow borders instead of the previously seen blue and green. The backs were likewise printed with a yellow background, but unlike the company’s other ’86 products they were given a vertical layout and consisted solely of textual descriptions of what was being highlighted. The timing of the set’s production filled the sales gap between the arrival of The Rookies and the December/January shipments of the upcoming ’87 Donruss flagship set. This necessitated some quick writing on behalf of the company’s editorial staff, as results of voting by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America are not announced until the conclusion of the World Series. Among the last awards to be announced are the AL and NL Rookies of the Year. With official release of ROY results not taking place until these cards were already rolling off the printing press Donruss had to guess as to who would take home the awards. For the second year in a row the correct rookies were identified by the company, though bets were hedged by labeling winners Jose Canseco and Todd Worrell as the “Donruss” Rookies of the Year.

An exceedingly rare variation exists for this card in which the amber colored “Highlights” logo is printed entirely in white. The error is present across the entire checklist with several complete white-lettered sets making it out into the wild.

Which Would You Rather Have?

I feel safe in assuming that anyone reading this far into such a lengthy post is a baseball card collector. I have been trying to give impressions and background information on one of the best known pieces of cardboard. Despite being just as old today as a Stan Musial rookie was to collectors back in 1986, there are very few hobbyists out there who don’t already have some sort of story or at least passing knowledge of the card.

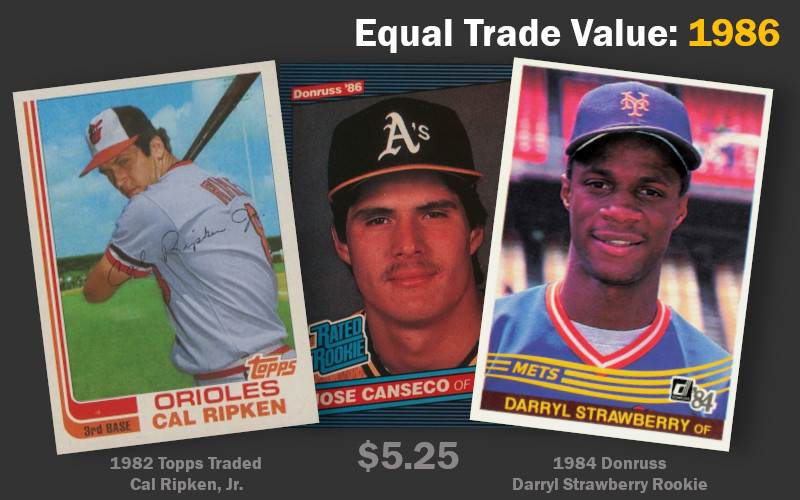

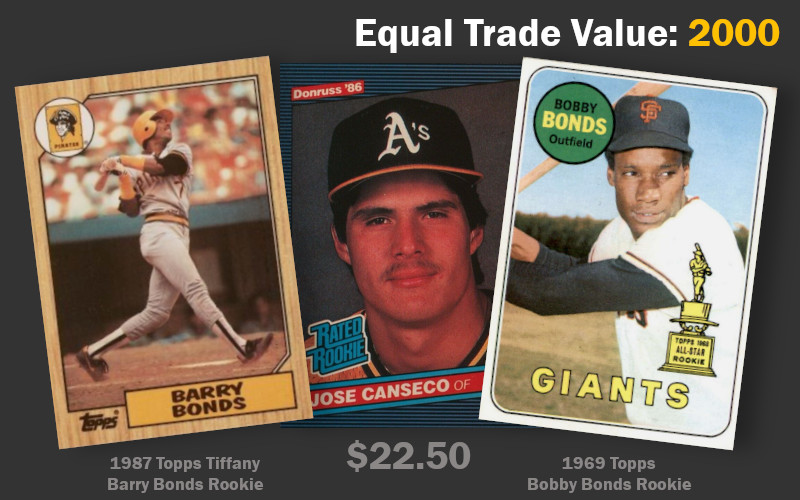

Instead of filling readers’ brains with more generic sounding details about the card, I will endeavor to tell the story of the ’86 Rated Rookie’s rise and fall through other cards. After all, that is what baseball cards have long been about: Trading them for each other. Growing up, my friends and I quickly saw our trading activity coalesce around one simple rule: No cards could be exchanged between parties unless a mutually accepted price guide provided equal value between the stacks of cards changing hands. What follows are a selection of cards that could have conceivably been part of equal trades at various points in time, each measured by the average high and low prices reported in the December edition of Beckett.

The mania for rookie cards was in full swing by the time the mid-1980s were upon collectors. Canseco was king of the current crop, having taken home the 1986 American League trophy. He was the latest in a run of some of the most successful ROY winners in quite a while. Cal Ripken had won the hardware in 1982 and collectors were valuing his 1982 Topps Traded card at the same level as the Canseco Rated Rookie. At this point Ripken was a more popular player but collectors of that era preferred pack-issued rookies like Canseco to those appearing in postseason Traded/Update sets. In their eyes this Ripken rookie was inferior to the multiplayer one appearing in the flagship Topps release.

Aside from Canseco, who wouldn’t make a pop culture impact for several years, the baseball player who most transcended the boundaries of the sport was Darryl Strawberry. Like the other two athletes, Strawberry had captured Rookie of the Year honors and was the undisputed heart of the lineup for the World Series champion New York Mets. Still seen as the reincarnation of Willie Mays in New York, anyone offering to trade one of his rookie cards for someone else was making a statement.

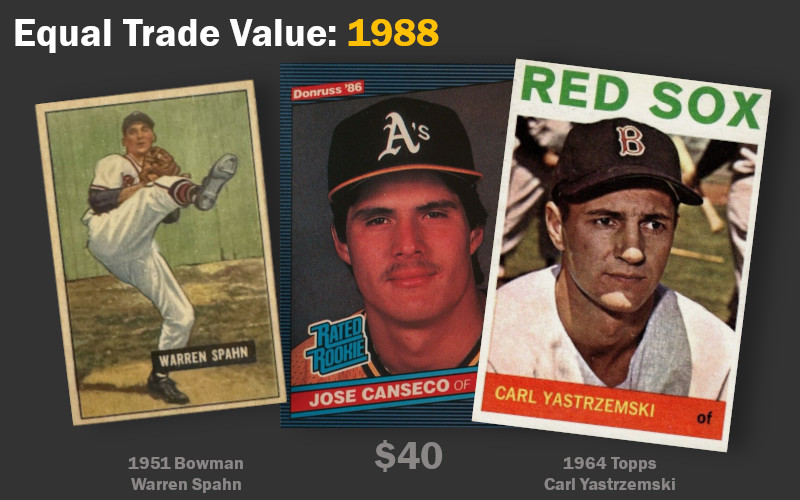

The intersection of Canseco’s baseball skill and propensity to boast came to a head two years later in 1988. That year he famously bragged that he could become the sport’s first 40/40 player despite only having 31 career stolen bases across three years of appearing in an MLB uniform. The spectacle of watching a season-long race made his name the one to be followed in daily box scores each morning in the same vein as a hitting streak or home run chase. He did indeed hit the 40/40 mark and the resulting demand nearly quadrupled the going rate for his rookie card, making the ’86 Donruss card a regular feature on the Beckett Hot List.

Collectors were taking note, not just picking him up as “another good rookie” but viewing him as being on the same trajectory as top tier Hall of Famers. Rookie cards of baseball legends still existed on a completely different level from those of modern players, but the price increase seen for the Rated Rookie suddenly put it on par with early career cards of some very big names. By the end of the season a newly pack-pulled Canseco rookie could be readily exchanged for a 1951 Bowman Warren Spahn or a 1964 Carl Yastrzemski. While vintage and modern collectors do not usually see their interests overlap, the excitement in baseball that season brought more than one vintage enthusiast to the bargaining table.

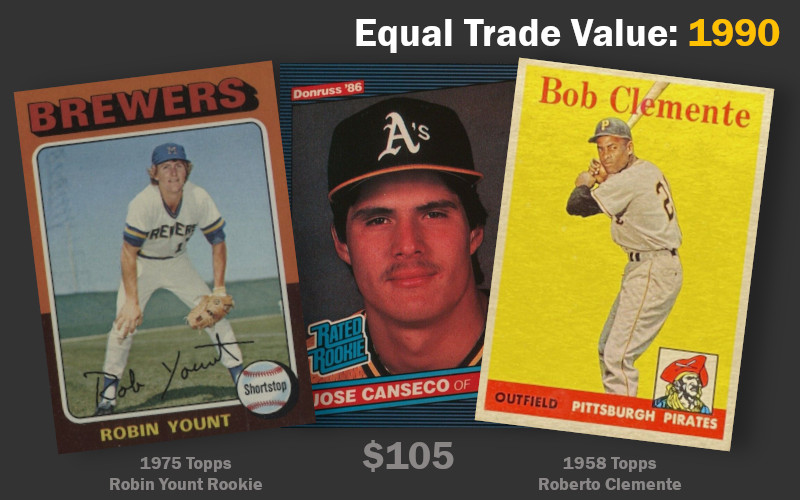

The peak of Canseco’s popularity overlapped a period in which the going rate for popular baseball cards underwent a step change to the upside. Many cards doubled or tripled in value, but Canseco’s combined this with the heady growth of the previous two years. The hobby had seen a massive influx of new participants who all wanted the key card of the current star, and this was the uniform answer to their inquiries as to what that might be. The card began the decade as one of only two flagship 1980s rookies to crack the $100 mark on a regular basis. When nostalgic collectors talk about this card commanding triple digit prices, this is the period they are remembering.

Vintage cards were seeing increased interest in this period as well. While Canseco largely stood alone in terms of ’80s cardboard popularity, collectors were just as eagerly scooping up older rookies. Robin Yount’s 1975 Topps debut was particularly desirable at this time following his 1989 MVP performance and the realization that the guy who had more hits than Pete Rose in his 20s was on the cusp of collecting number 3,000.

Big names from the Golden Age of cards could be considered to have been on par with the Canseco and Yount rookies. Roberto Clemente’s classic 1958 Topps card is just one of several top level cards that were considered equally desirable. Exchanging a Canseco for Clemente would have worked out extremely well for a collector, though such a deal would have been accompanied by some nervousness at the time.

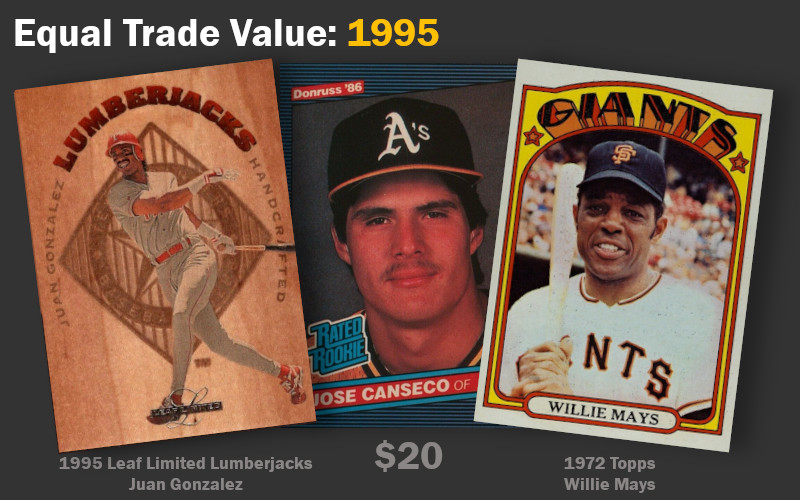

I don’t know who really imploded first: Jose Canseco or the game of baseball itself. By the end of 1995 he was on the wrong side of 30 years old and had sat out at least 30 games with injuries in 6 of the last 7 seasons. Baseball is littered with broken power hitters and collectors have a habit of moving on, regardless of how exciting their play in the brief instances where health allows. Canseco’s off-field antics and less than stellar defense wore on fans who found themselves wondering why they should be cheering the guy. Canseco was still somewhat popular, but was no longer the star he had once been. His key cards no longer commanded the same respect as 1950s classics of Hank Aaron and Willie Mays, instead being relegated to the same standing as the end of career appearances of these players in 1970s Topps sets. Those still following Beckett’s Hot and Cold List found Canseco consistently near the top of the latter and completely absent from the former.

Collectors and fans were moving on to other pursuits as well, adding to the wholesale dumping of Canseco rookies. Junk wax fatigue was setting in with the hobby collectively realizing the cards of the previous 10 years had been massively overproduced relative to long term demand. There simply weren’t enough people who didn’t already have a Canseco rookie to warrant any sort of premium price. Couple this with the disillusionment and exit of those who had entered the hobby solely because of rising prices and the excitement of a fast buck from a pseudo-form of sports gambling presented in cardboard form. Rookie cards remained popular, but were increasingly taking a back seat to limited edition inserts randomly appearing in packs. New names like teammate Juan Gonzalez were replacing Canseco atop the home run leaderboard and collectors could be found swapping their Rated Rookies for foil embossed cards of “Juan-Gone.”

The walking away of card collectors was a multiyear process, but was supercharged by the effects of the deeply unpopular MLB players strike on 1994-1995. Reaching an impasse in labor negotiations, baseball players refused to take the field for the remainder of the 1994 season and continued their holdout into early 1995. Fans, upset at seeing players shun highly publicized compensation offers that were well above their own, did not have sympathy and largely turned against the same athletes that they had once collected. As one of the sport’s previously highest paid players, Canseco drew his share of criticism for the walkout. He even drew more attention to lesser followed aspects of the strike, such as when he joined umpires on a picket line following their own strike which resulted in the sport using replacement umps for the remainder of the ’95 season.

Baseball was seemingly back on track at the end of the decade, helped in popularity by multiple assaults on the single season home run record. While most eyes were on the battles between McGwire, Sosa, and Griffey there had been a change overtaking of the best power/speed names in the game. Barry Bonds set his sights on overtaking McGwire’s record and would successfully do so with 73 in 2001.

Bonds and Canseco had arrived on the scene at about the same time, and while Canseco grabbed an early lead in the tally of MVP trophies, Bonds soon began racking them up in numbers not seen in decades. Bonds cards had always been in some demand but were only just now reaching their heights of popularity. The same can be said about some of the less visible cards of the Junk Wax Era. Topps’ high gloss Tiffany issues were beginning to gain collector traction and hobbyists could have conceivably engineered a trade of rising and waning stars.

Barry Bonds’ popularity was likely held back from its potential by several issues. His personality elicits strong responses and a preference for working through things away from teammates and the press did little to help his public image. Bonds’ father, Bobby, very nearly had baseball’s first 40/40 season and only lost out on the distinction due to the scrubbing of a partially played game due to rain. There was a moment in time when rookies of either Bonds could be exchanged on an even basis for a Canseco rookie.

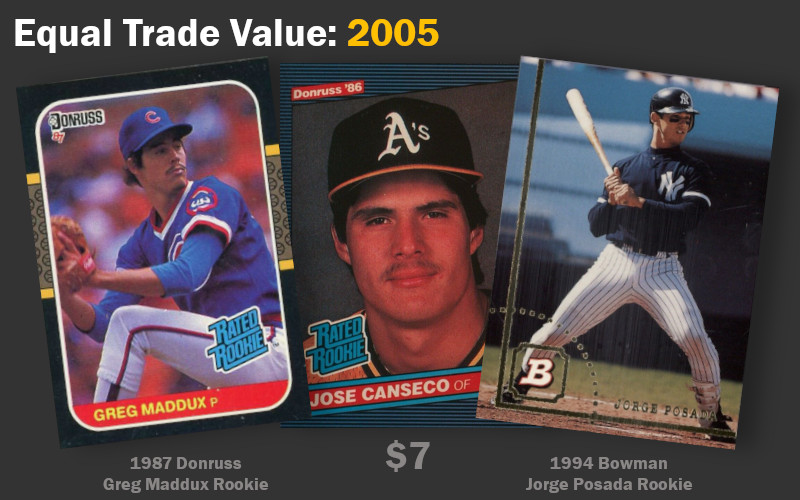

2005 was nearly 20 years ago, and while Mark McGwire famously didn’t visit Conress to talk about the past, Jose made a second career of it that year. That was the year he jumped to the front of the parade of those questioning the use of PEDs in baseball with the release of his memoir Juiced. Names were named, testimony was given, and Canseco finally admitted what sports writers had been reporting since 1988: His mustache had been the only natural part of his game.

Enthusiasm for card collecting took another dive akin to the one encountered in the strike. Canseco’s rookie, like many of the game’s tainted stars, plummeted in value by nearly 70%. Canseco himself was no longer an active player, claiming (probably correctly) that teams were purposely avoiding him. It seemed as if all of Junk Wax was burning down, not just those that had helped light the inferno engulfing the reputations of anyone who could hit the long ball. At this point the Donruss rookie card of Greg Maddux, arguably one of the top five pitchers of all time, could be exchanged for what was now described as an infamous baseball card. [Side note: Bad mustaches were apparently popular in the mid-’80s]

There were some glimmers of hope. The Yankees were in the middle of what would eventually be recognized as a resurgence of the team’s dynasty producing rosters. Canseco won a World Series ring as part of this, going 0 for 1 with a strikeout in his only postseason appearance with New York. Collectors who had last watched him in the World Series were now a jaded and a decade older. His Rated Rookie was now changing hands on a 1:1 basis with the debuts of New York favorites like Jorge Posada. Collectors had moved on.

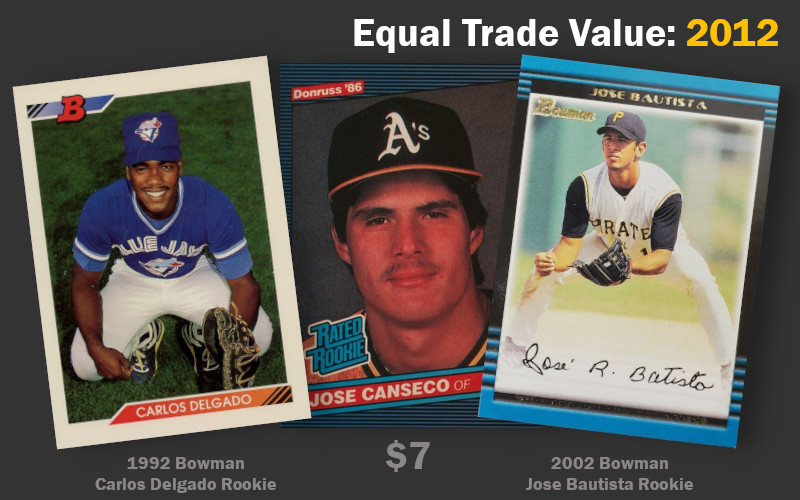

In the years following Canseco’s retirement there were still players that boasted similar playing styles. Collectors in 2012 could find similar numbers from his former teammate Carlos Delgado or from active Blue Jays power hitter Jose Bautista. Both had rookie cards with the same market demand as the 1986 card, though the attraction of the Rated Rookie logo had been supplanted by the rise of Bowman as being all things rookie related. A shift had happened in the baseball card world and for a time each of these cards were floating at the same equilibrium level.

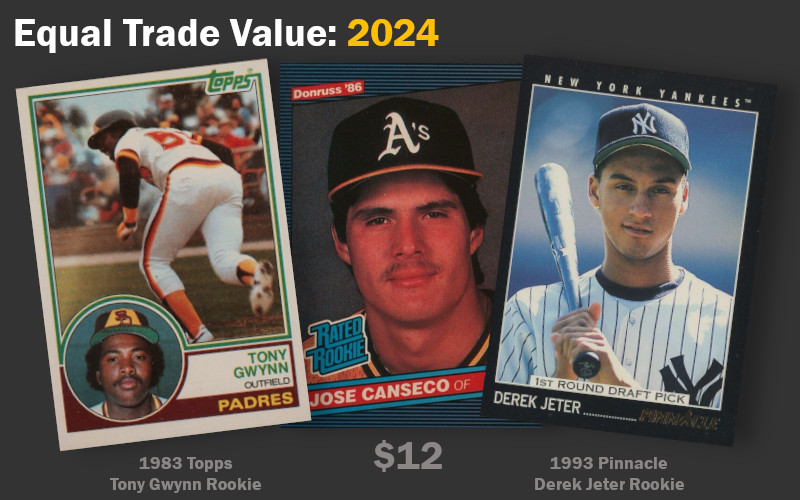

Here’s what makes flipping through old baseball cards with which you have a history great: Each card you recognize brings with it its own memories and relative values against your internal valuation scale. I can go to any major online collecting platform and land either of these three cards in decent shape for about $12. It blows my mind that the Gwynn card can be found at this price point, but that may be the conditioning of seeing it at 2-3x that level in price guides for much of my life. Even more amazing is the thought that Gwynn was still with us in 2012, the previous stop in this valuation timeline.

When I put this card into my wallet at the beginning of 2021 I repeatedly thought “I can’t believe I’m doing this” I had no problem destroying other cards, but this one reached right back in time. It wasn’t the monetary aspect of bending up this card, as the eight bucks I paid for this off-centered copy is less than most unopened modern packs retail for. Instead, it was the act of destroying something almost sacred (my childhood collecting goal) in order to make it better (I’m playing with cards again). Canseco and those he inspired likewise made a mockery of baseball statistics, but it sure was fun to watch.