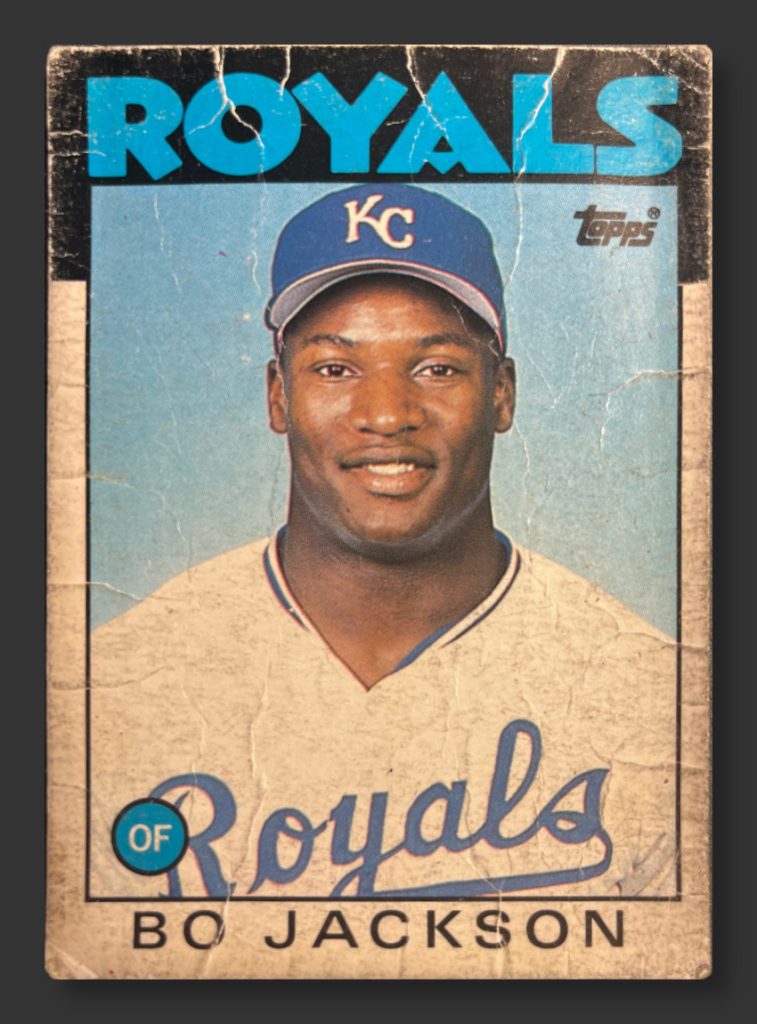

Not every baseball card you see displayed under glass is in perfect condition. At some point you expect cards to have rounded corners and wrinkles. Whether it hails from the hobby’s golden age, has reached a golden anniversary, or is simply old enough to nab that senior discount at Golden Corral, the recognizably classic pieces of the hobby look out of place without some wear and tear. When I first began collecting in the early 1990s, I imagined the junk wax names being added to my binders would one day be just as iconic as those well-worn pictures of Willie Mays and Gil Hodges. After all, isn’t that what happens after 35 years go by?

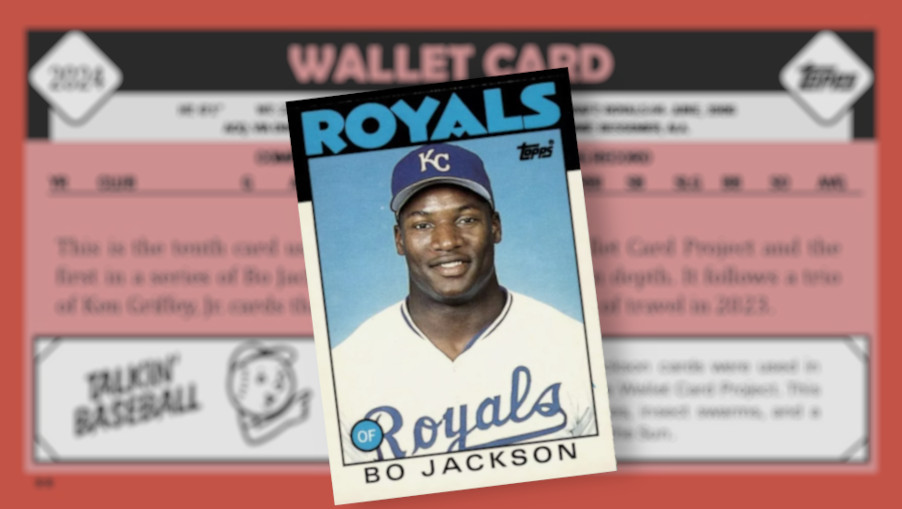

Things did not quite turn out that way. Oversupply of newly printed cards, a shift among parents from throwing out their kids’ cards to saving them as a potential windfall, and a tendency towards immediate preservation kept these bits of cardboard from achieving the same weathered status as those classic cards. A few years ago I resolved to do something about that. I started carrying some of my favorite cards in my back pocket where they quickly achieved the same patina of wear as the cards I had once viewed with awe at the ever present junk wax era card shows. These “wallet cards” are changed out annually on my birthday, exchanged for several more names to expand my growing collection of creased cardboard.

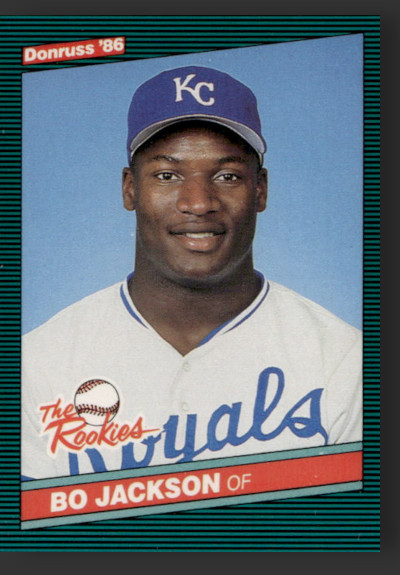

Last year’s selections all featured Bo Jackson and included his rookie card from the 1986 Topps Traded set. While Bo’s story is well known at this point, the real-time experience of witnessing the unfolding of his career(s) was filled with unexpected twists, including the very existence of this card.

That Was…Unexpected

Coming off winning the Heisman Trophy in 1985, the playbook for Bo Jackson at the start of 1986 looked like this: Score a couple touchdowns in the Cotton Bowl on New Year’s Day. While away the spring by knocking the cover off baseballs for Auburn. Get picked first overall in the NFL Draft. Become his family’s first college graduate. Wrap up the year by carrying the Tampa Bay Buccaneers to their first playoff victory since 1982. That’s how things were supposed to go, and the extent to which people still expected it to happen when things unraveled is a testament to how inevitable it all seemed.

And why should the calendar play out any differently? Jackson was certainly on board with this itinerary. That’s why he hopped inside Hugh Culverhouse’s plane in March for a short trip to meet with the Buccaneers, holders of the upcoming first draft pick, and undergo a pre-draft physical. 10 Days after lifting off the tarmac, Jackson’s NCAA career crashed and burned on the return flight.

The trip was a fly-in, fly-out same day affair timed so Jackson could make it back to Auburn in time for a regularly scheduled baseball game. Travel time from the airport cut into his turn in pre-game batting practice, drawing inquiries from coach Hal Baird about his whereabouts. Informed by Jackson’s teammates that he had accepted a flight, the coach benched his multisport outfielder until the effect of the gratis air travel on his playing eligibility could be sorted out. By the next afternoon he was no longer part of the Auburn Tigers baseball team. There wouldn’t be a degree or graduation either for the college senior, at least until he returned to school a decade later.

Still, he was the reigning Heisman winner and the NFL draft was only weeks away. Dismissal from the Auburn lineup had clearly upset Jackson, prompting the Buccaneers to press their recruiting effort harder. Multiple meetings were arranged to allow potential teammates the opportunity to sell him on signing with Tampa. These meetings had the opposite effect with players quickly letting Jackson know owner Hugh Culverhouse did not have their interests at heart. Culverhouse unconvincingly portrayed Jackson’s NCAA violation as an innocent oversight, a bit of a reach considering professional organizations are well versed in the process of recruiting minor league football college athletes within the NCAA statutes. Sports columnist Dick Young, not a stranger to stoking clubhouse drama, wrote a piece arguing the only plausible explanation was a conscious effort to close off Jackson’s alternatives. Whatever the veracity of this claim, Jackson became adamant that he would be unwilling to sign with Tampa Bay if selected by the team in the upcoming draft. April 29th arrived and Tampa kicked off the draft by claiming the rights to Jackson’s services with the opening pick.

Jackson did not immediately sign. His name was present in the upcoming June MLB draft and was attending games as the guest of several organizations showing interest. He made visits to the Blue Jays, Angels, Pirates, and Royals, among others. Every one of these teams were aware of his NFL draft status, the $7 million offer awaiting his signature, and the value of their own first round picks should he opt for football over baseball.

…Really Unexpected

Of course, Bo Jackson is not an unknown person to readers of today. You already know that he was selected by the Kansas City Royals in that 1986 draft class. You already know there is an awesome card featuring the team’s new outfielder in the ’86 Topps Traded set. OF COURSE JACKSON WAS GOING TO PLAY BASEBALL. Why was this so unexpected by fans 39 years ago?

Here are a few reasons, any one of which would have swung most athletes’ decisions towards signing with the Buccaneers:

- Money. Jackson was offered a $7 million deal by Tampa against $5 million from the Royals. The bigger money was in football, even if he sat out for a year hoping a different team would draft him.

- Playing Time. Jackson would not have been relegated to the practice squad in Tampa, but rather put onto the field for the very first snap of the season. His NFL career would start the second he signed his name to a contract. Baseball, on the other hand, was a sport in which he would certainly begin in the minor leagues with no guarantee of ever progressing far enough to taste MLB pitching. Jeff King, the number one overall pick in the ’86 draft, did not reach the majors until midseason 1989.

- Relative Skill. It is no secret that Bo Jackson was better at playing football than baseball. He was the top college player in his senior year, taking home that Heisman Trophy. Baseball, a sport in which the average D-1 hitter batted .301 in 1986, saw him manage to hit only .246 in his final year. That’s a step down from his junior production and a problematic sign for someone who hopes to one day face a major league curve ball.

- Team Resources. Professional baseball isn’t some sort of fantasy draft. Player selection is just one part of the equation. General managers operate on the assumption that each draft choice and the accompanying contract offer changes the opportunity set available to the team. Funds allocated as a signing bonus could just as easily be used to shore up the contract of a veteran All-Star threatening to test free agency. Early draft choices can be turned into chips to trade other teams for players that can have an immediate impact on a roster. Using one of these picks by definition destroys its trade value. Any team selecting Jackson was burning very valuable draft real estate should he take the more probable course of action of signing with an NFL team. He had, after all, already been drafted by and turned down the New York Yankees (2nd Round!) and California Angels in previous years.

- Championships. Bo may very well have become an NFL-only player had he been selected by the Pittsburgh Pirates with their first round draft choice. Prior to the draft he had let it be known that he wanted to play for a team capable of winning championships, something the Pirates were decidedly not at that time. This would seem like the sort of generic “I’m here to win” platitude given off by most new arrivals, though in this case he appears to have meant it. As the defending World Series champions, the Royals were uniquely situated to have credibility with Jackson.

- School. Bo did not complete his degree in 1986. Given his animosity towards the Buccaneers and the likelihood of finding another receptive team in the 1987 NFL draft, it was altogether possible that he would run out the clock on Tampa’s draft rights and wrap up his degree in the interim.

I cannot stress this enough: Jackson playing for the Royals was unexpected. The newspapers whose coverage I combed through in researching this draft were uniform in their prediction that he would choose football. The general managers quarterbacking the MLB draft were all but certain that any pick used on Jackson would be wasted. He had previously turned down offers from two teams, and nobody was willing to make an offer so rich as to top the outstanding bid from Tampa.

Even the news of his draft selection was a surprise, arriving a week earlier than expected. MLB rules in effect during this period made the results of the first round immediately available but forbade releasing the results of subsequent rounds for at least a week. Jackson was picked up in the fourth round as the 105th overall selection, embargoing the news by the nature of where his name fell in the draft order. The attorneys representing Jackson, who had all of a few weeks of sports management experience, proudly announced his selection ahead of the expiration of the mandatory delay. With the news out in the open, Kansas City confirmed the selection. A few weeks later his legal team called a press conference to announce his decision to sign with the Royals, an event Tampa was reportedly unaware of until it happened.

The Unexpected Card

Here’s something it took a while to understand as a young collector: Baseball cards are generally made well before a season begins. Things that happen during the year get reflected in the following year’s cards. It takes quite a bit of time to source photographs, write copy, set up layout templates, build proofs, and calibrate and run printing equipment. This all takes place before a manufacturer even gets near packaging and distribution. For a card to hit store shelves at the start of Spring Training it is already going to be somewhere in the design process shortly after the previous World Series.

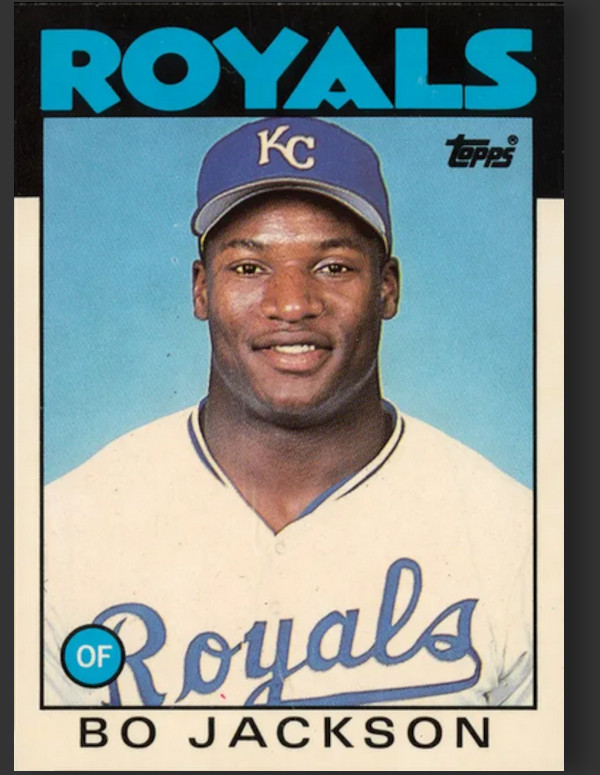

The fact that Topps issued a Jackson card at all in 1986 is a minor miracle. Topps reserved space for several dozen rookie call-ups in its year end Traded sets. The company was limited to portraying players who had been part of major league rosters and was not in the business of producing minor league cards. All but one rookie in the ’86 Traded release had made his MLB debut months before the All-Star break. Jackson, meanwhile, spent much of the ’86 season sorting out his position in professional sports drafts, negotiating contracts, and getting his first taste of pro baseball with the AA-level Memphis Chicks.

Jackson rocketed to the majors faster than anyone expected. It’s not often you see a guy who logged a sub-.250 batting average in college jump two levels of brief minor league service to the majors. He joined the big league club on September 2 as an expanded roster call-up. His first plate appearance and the ensuing single off Steve Carlton started the clock for card manufacturers to get a card to market.

Beyond the logic of whether or not the card should even get into a set, there is the small matter of the photograph. Topps products of the era typically sourced their images from contract photographers attending Spring Training or a handful of select MLB games in an earlier season. Jackson didn’t appear in a Royals uniform until the midseason week following his signing. He spent a few days practicing with the team in Kansas City before playing for Memphis. Perhaps Topps could have obtained a usable image through the purchase of a freelance shot from Bo’s September debut. Perhaps they could have edited the photo and slotted it into a production-ready template. Perhaps. That would have taken too much time. Aside from Jackson, baseball’s most recent rookie to make his debut in the set had made his first appearance back in May – a month before Jackson was even drafted. A current year draft pick was unheard of in one of these checklists.

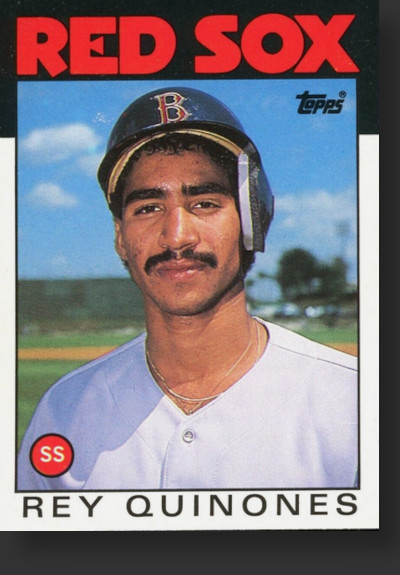

The checklist is typically finalized around the trade deadline and the cards packaged and sent off in time to catch the last bit of World Series-inspired collector enthusiasm at the end of the year. The truth is that Topps and their marketing team were ready to go to press with the set and Bo Jackson card, provided he could just get that one precious MLB appearance. The set had already been finalized, as evidenced by the release’s Rey Quinones rookie depicting him as the Red Sox shortstop. Quinones had been traded to the Seattle Mariners in August, a detail that would have surely been addressed had the Traded set not already been laid out for production.

The solution to the problem of sourcing a photograph was taken care of by the Royals during the initial days of Jackson signing with the team. Each MLB team takes portrait shots of players for use in marketing materials and Jackson was duly photographed as part of his first day with the organization. These are used in club media guides and freely handed out alongside relevant news releases. Topps and competitor Donruss both employed the publicity still in their year-end products. Same pose, same uniform, same blue background. Same exact image.

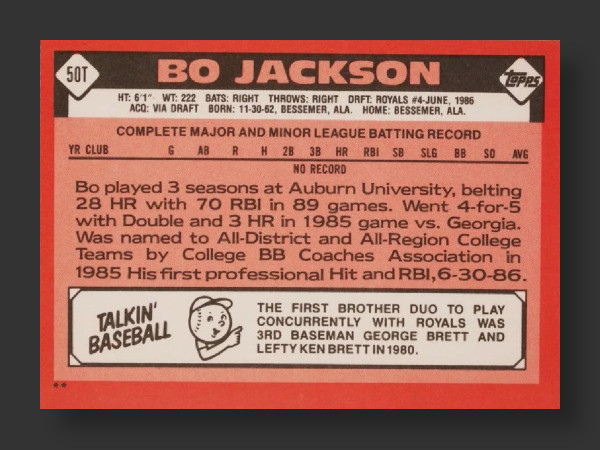

The back of the card is 100% baseball with zero mention of football. No minor league or college statistics are presented in the standard table near the top. Much in the way future generations would come to see Bo’s career, the use of statistics was eschewed in favor of a generous helping of stories and highlights.

The bulk of the card discusses Jackson’s exploits on behalf of Auburn University, highlighting how often he connected for home runs. There is a mention of a 4-for-5 performance against Georgia. The April 2, 1985 game was used by Michael Martinez of The New York Times as an example of a typical Bo Jackson moment1. Martinez recounts the Auburn junior being heckled as he grounded out and then took his position in center field in the home team’s first ever night game. Jackson came back to the plate in the fourth, recalling that “everything went into slow motion and got quiet” before sending a ball straight into one of the newly installed light towers.

The biographical sketch wraps up with an inadvertent run-on sentence, apparently lacking a period after “1985” in the bottom line. Mentioned at the end of this blurb is Jackson getting his first professional hit and RBI on June 30, 1986. This came with the Southern League’s Memphis Chicks, with Jackson knocking in a run with a first inning single off of Mitch Cook. Not mentioned is Jackson’s first MLB hit, which arrived in his first big league plate appearance in the form of a single off Hall of Famer Steve Carlton.

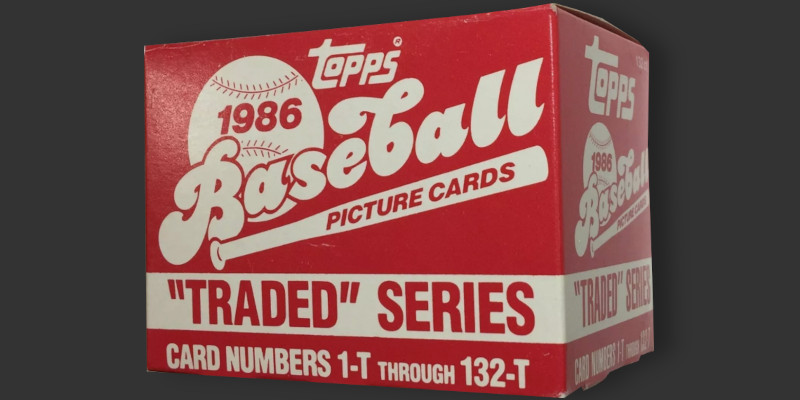

Production and Distribution

As a late season product, this card was only available as part of complete 132-count sets marketed to hobby shops and assorted big box retailers. The card was available in two varieties; the familiar base version and a much more limited edition featuring a gloss coat similar to that of photo paper. Known as “Tiffany” cards, the easiest way to differentiate them from the regular variety is to look on the back for a lack of asterisks in the lower left corner.

Topps never published its final production numbers for the ’86 Traded set, but did helpfully serial number the boxes containing the Tiffany cards out of 5,125. Using the set’s most popular card (Barry Bonds) as a reference, I have found the base version to be advertised for sale 90-100x as often. This implies the overall print run of my Jackson rookie to be somewhere in the neighborhood of 500,000 copies.

Topps revisited the ’86 issue multiple times in the ensuing 39 years, releasing dozens of cards either copying the original or being obviously inspired by it. I’ll spare you from reading through the list after having subjected readers to 70+ versions of the set’s Jose Canseco card just a few days ago. Suffice it to say I would never trade an actual ’86 Bo Jackson for one of the newer versions.

On The Subject of Trading

Trading baseball cards is an art form, though like the game itself is heavily reliant on the cold reality of numbers. Growing up in the early ’90s, my grade school friends and I had adopted a rule that transcended all age groups: All trades had to involve each participant walking away from the deal with equal Beckett or Tuff Stuff price guide value, the choice of which was driven by whichever counterparty had the more advantageous negotiating position. This kept some semblance of fairness in our trading activity and prevented parents from negating trades on the grounds that their kid was being taken advantage of. Moms simply do not understand the binding nature of declaring “Blackjack! No trade back!”

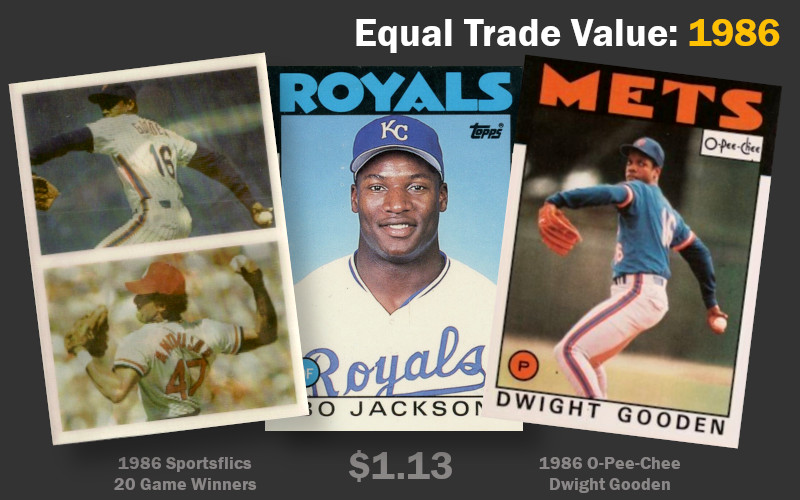

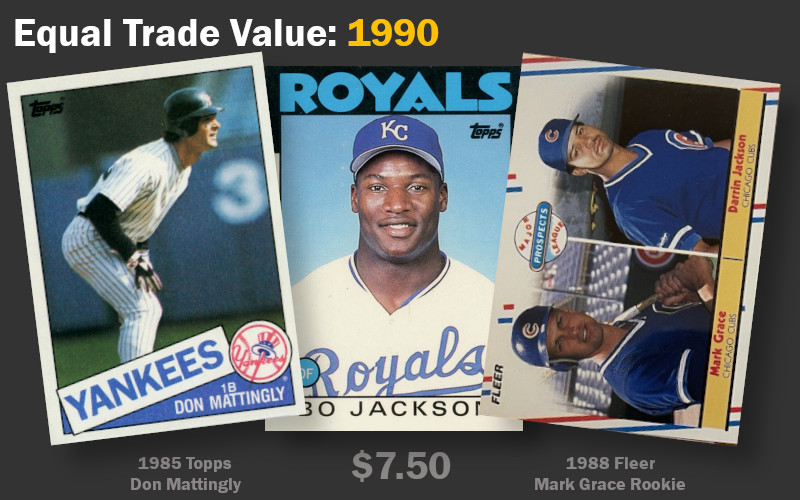

I was one of the kids who adhered to Beckett‘s trade values whenever possible and I measured the desirability of my cards by the changing up and down arrows accompanying much of my collection. What follows is a sampling of the kind of cardboard firepower that would have been required through time to start a trading negotiation in my neighborhood for a Bo Jackson rookie. Cards are presented showing identical average values between the price guide’s high and low column listings within each year’s final print edition.

By some measures a year end 1986 Beckett would be alien to collectors who learned about the hobby just a decade or two later. For starters, the ’86 November/December edition (the final issue each year covered a longer time frame than usual) identified the Topps Traded set as “Topps Extended.”

Space constraints crowded out many of the card issues that filled the pages of the price guide in its early years. Topps’ products followed a listing for Sportflics’ debut release, a product that would soon be relegated to the pages of more comprehensive annual guides and replaced in the monthly guide by more popular cards. This period also saw Canadian issues from Leaf and O-Pee-Chee reported on a monthly basis before they too were dropped from the monthly cadence. This isn’t to say the cards weren’t popular. Sportsflics in particular stands out as being the most highly valued 1986 release by year end, eclipsing the price collectors were then putting on their blue-bordered Donruss cards.

Jackson was already a well-known name at this time given the combination of his college football award, the ensuring draft controversy, and a decent rookie season. At the time Beckett traditionally pictured a card from each set above the relevant pricing data and the Jackson card was selected by the editorial staff as the exemplar for ’86 Topps Traded. This was a card that was seen as one of the highlights of the 132-card checklist, though collectors kept Jackson’s position in relative perspective. No collector would give up their base ’86 Topps Dwight Gooden to obtain a copy, but they might be persuaded to exchange their lower tier O-Pee-Chee model for one. The same went for the vaunted Sportsflics release. While you’d have to give up multiple Jackson Traded cards to get a Gooden base card from the set, an enterprising collector could probably swing a deal for Gooden’s appearance on a multiplayer card highlighting the previous season’s six 20-game winners.

Jackson’s popularity peaked right around 1990, putting anyone with his cards in prime position to improve their collection with a well-timed trade. I distinctly remember forking over $10 in cash at a card show for a Don Mattingly second year Topps card in early 1991, and probably would have done the same for a Jackson rookie had one been offered on similar terms. This marked the top of Jackson’s popularity, as just two weeks into the new year he suffered the hip injury that immediately ended his NFL career and led to a few shortened seasons in baseball.

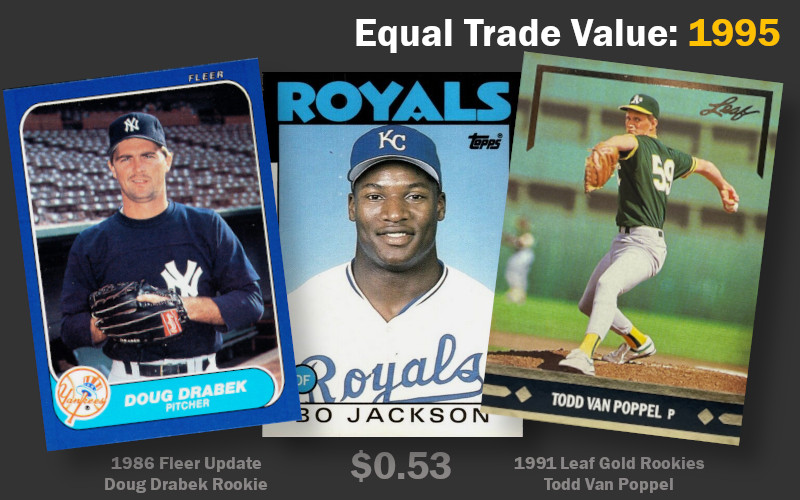

Five years later Jackson’s career had ended and the magic was gone. His entire career unfolded in the heart of the Junk Wax Era, leaving no shortage of cards for those still looking to snag a memento of his time in baseball. At this point many collectors considered Jackson’s ’86 Traded to be just another busted prospect, a player who showed the potential to be something great but was derailed too early to leave a lasting impact. The story had played out dozens of times before and given the massive overproduction of these cards no one was in a hurry to trade for a new copy. You would have just about as much luck trying to move rookies of Doug Drabek (Cy Young Award and solid pitching, but no chance at Cooperstown) or Todd Van Poppell (the next “Ryan Express” barely cleared the station).

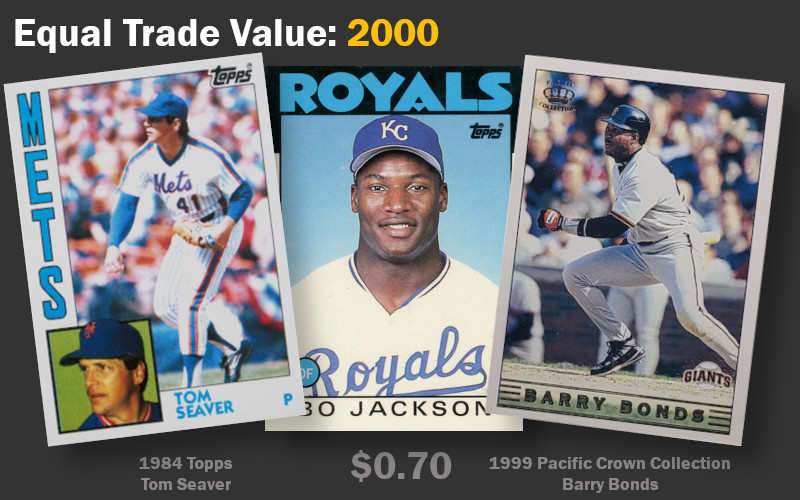

Five years later collectors had proven to be at least a bit nostalgic for reminders of Bo’s career. A Jackson rookie could now command a late career base card of a Hall of Famer. Tom Seaver? Sure, I’ll trade. One of a bazillion different Barry Bonds cards produced just before he destroyed the home run record? Any of them looked comparable.

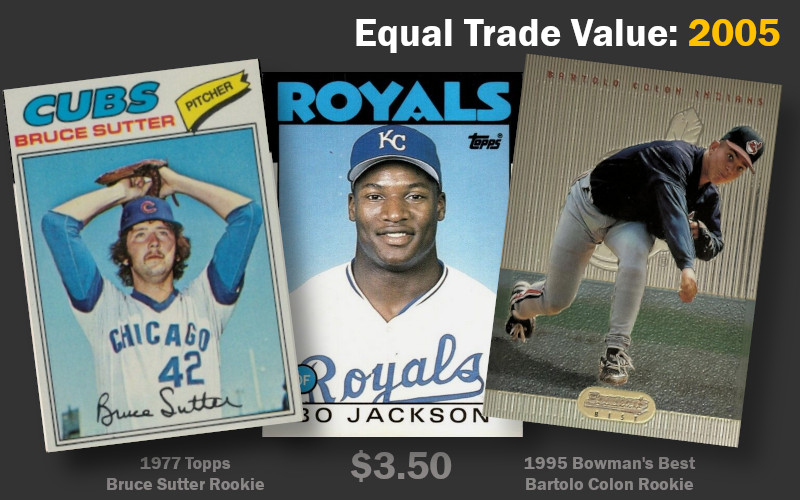

Anyone accustomed to the rhythms and relative value expectations of trading in the previous decade was in for a shock halfway through the 2000s. Jackson rookies were once again in demand. It didn’t matter that his career abruptly hit a wall, he was one of the handful of players from his era that people wanted to remember. Suddenly this card was on par with a premium rookie of Bartolo Colon, winner of the 2005 Cy Young Award. Jackson’s ’86 Traded wasn’t the only rookie card moving up. A similar resurgence in interest saw collectors begin to seek out the 1977 rookie of relief pitcher Bruce Sutter as it began to dawn on the hobby that Sutter was on the verge of being elected to the Hall of Fame.

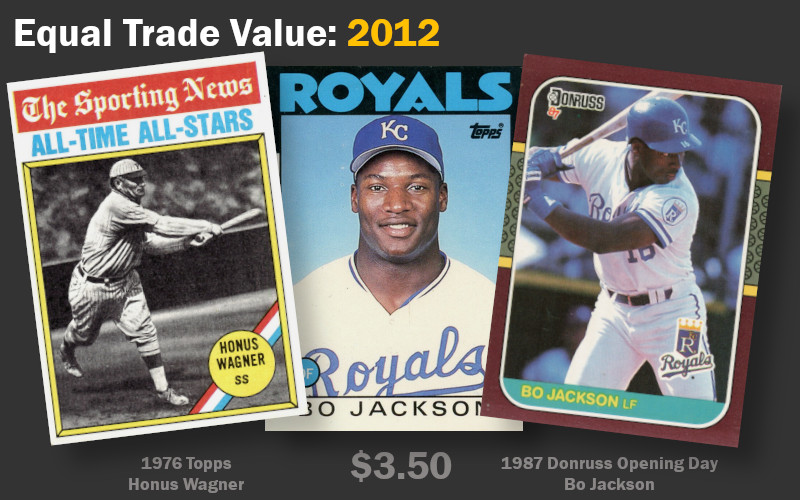

Moving forward another half dozen or so years one finds yet another subtle shift in the collecting landscape. Some of the forgotten cards of past eras were seeing renewed interest despite this period representing the nadir of the hobby’s overall popularity. Much of the past decade had been filled with relic cards containing (or at least pretending to contain) pieces of bats and uniforms worn by some of the game’s greatest names. Those that couldn’t afford a playing days Babe Ruth or Honus Wagner now had a run of non-reprint cards that they could collect. This generated additional interest in pack-issued cards from the 1970s and back and it is around this time that cards like the 1976 Topps All-Time All-Stars subset began to come out of dime boxes and into wider collections. You might even have to offer a Bo Jackson rookie in trade to get a ’76 Wagner.

At this time everyone seemingly already had any core junk wax cards that they cared about in hand. The marginal sets that had been largely ignored, however, were a different story. Donruss’ 1987 Opening Day set had been seen for its first decade of existence as the less attractive version of the company’s flagship set, but by 2012 the trade value of many cards were beginning to exceed that of their traditional counterparts.

Today Jackson’s cards seem to have regained much of their previous popularity with collectors, or at least those old enough to have trouble naming more than 10 Pokemon characters (the full extent of my personal subject knowledge). Price guide values are more or less useless at this point, bowing to the relentless pressure of getting real-time comparable sales data from the nearest app or browser.

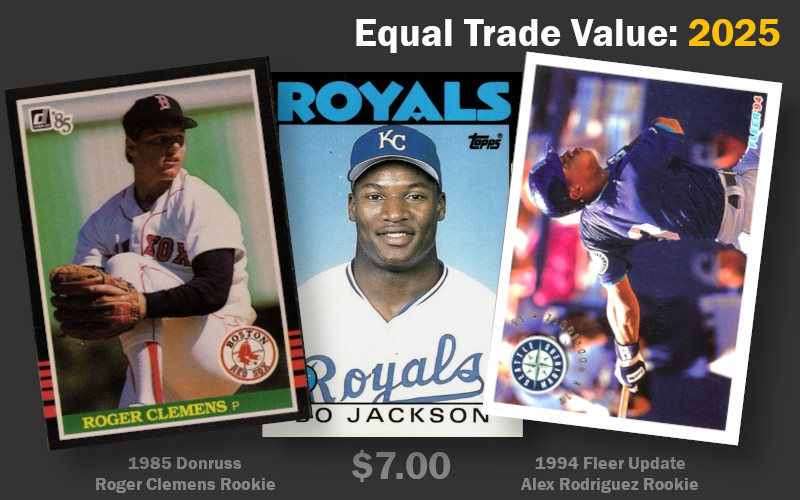

This month I have routinely seen this card changing hands at prices from $5-$10, the same kind of spasmodic 100% range observed for other cards that were once cornerstones of a well-curated modern collection. The condition sensitive black bordered ’85 Donruss rookie of Roger Clemens moves in this fashion, as does one of the tougher Alex Rodriguez rookie cards found in the ’94 edition of Fleer Update. Graded examples of all three go much higher but they do not really separate themselves too much. For all intents and purposes these are interchangeable.

The choice of this pair of potential trades serves to make another point about Jackson’s legacy. Collectors are willing to part with the rookie cards of perhaps the game’s greatest pitcher or a shortstop who hit roughly 700 home runs. The Jackson card, which represents a Hall of Very Good career cut short by injury, is just as popular for the same reason that these once highly sought cards have come down in price. Clemens and, to a greater extent, Rodriguez have been dogged by suspicions of their roles in the Steroid Era. Jackson’s resurgent popularity may very well be a reaction from fans of the era looking for someone untainted by PED speculation.

Bo knew how to become a baseball card legend all along.

- Martinez, Michael. “Bo” New York Times News Service. June 9, 1985. ↩︎