W.P. Kinsella’s Shoeless Joe tells the story of an Iowa farmer who builds a baseball diamond amid his crops and summons the ghosts of long-gone baseball legends. The farmer has to contend with mounting financial pressure as the ballfield prevents him from growing sufficient quantities of corn. At one point he discusses just how special Iowa’s dirt can be, noting that it seems to have a magical ability to produce miracles.

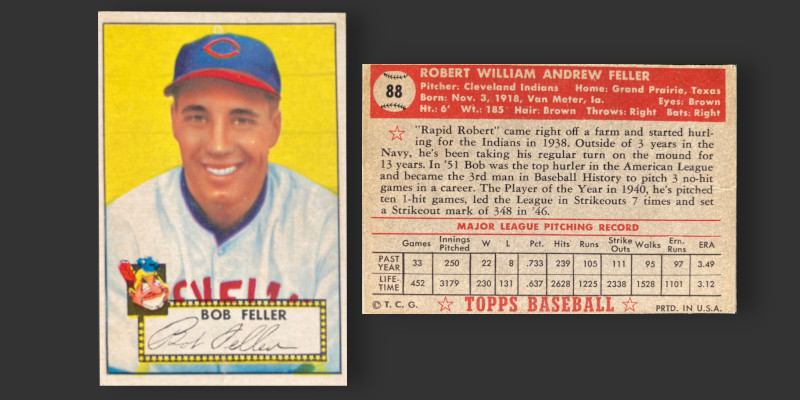

Bob Feller was born to an Iowan farmer just one year before Shoeless Joe and the 1919 White Sox would embark on a misadventure that culminated in a classic baseball story. After Bob’s arrival, his father set aside some of the farm’s acreage to build a baseball diamond, complete with stands and stadium-like amenities. The two practiced daily, setting the archetype for fathers like Earl Woods and Walter Gretzky who seemingly crafted their sons into legends of their respective sports. The field hosted regular local games and attracted paying crowds, giving a historical precedent to the Field of Dreams “people will come” monologue. At age 16 Feller signed with the Cleveland Indians in exchange for a signed baseball and a bonus of $1.

Feller could through the ball hard. Although exact measurements of velocity are harder to quantify than in today’s game, several methods indicate he was hurling fastballs as fast as 107.9mph. For perspective, Aroldis Chapman’s faster-ever pitch was measured at 105.1 mph and Nolan Ryan threw 108.5mph in 1974. Like both pitchers that came after him, Feller was a noted strikeout artist. He fanned 15 batters in his first major league start and went on to set the record for most strikeouts in a single game (18). He tied the then-major league record for career no-hitters (3) and set the high water mark for 1-hitters with 12. This latter record would be eventually tied by Nolan Ryan over a much longer career. Like Ryan, Feller’s only drawback was a propensity to give up some pitch control in exchange for greater velocity. This resulted in both routinely leading their leagues in walked batters and giving up a substantial number of home runs. Feller and Ryan’s names often appear next to each other with both producing similar numbers across their primes.

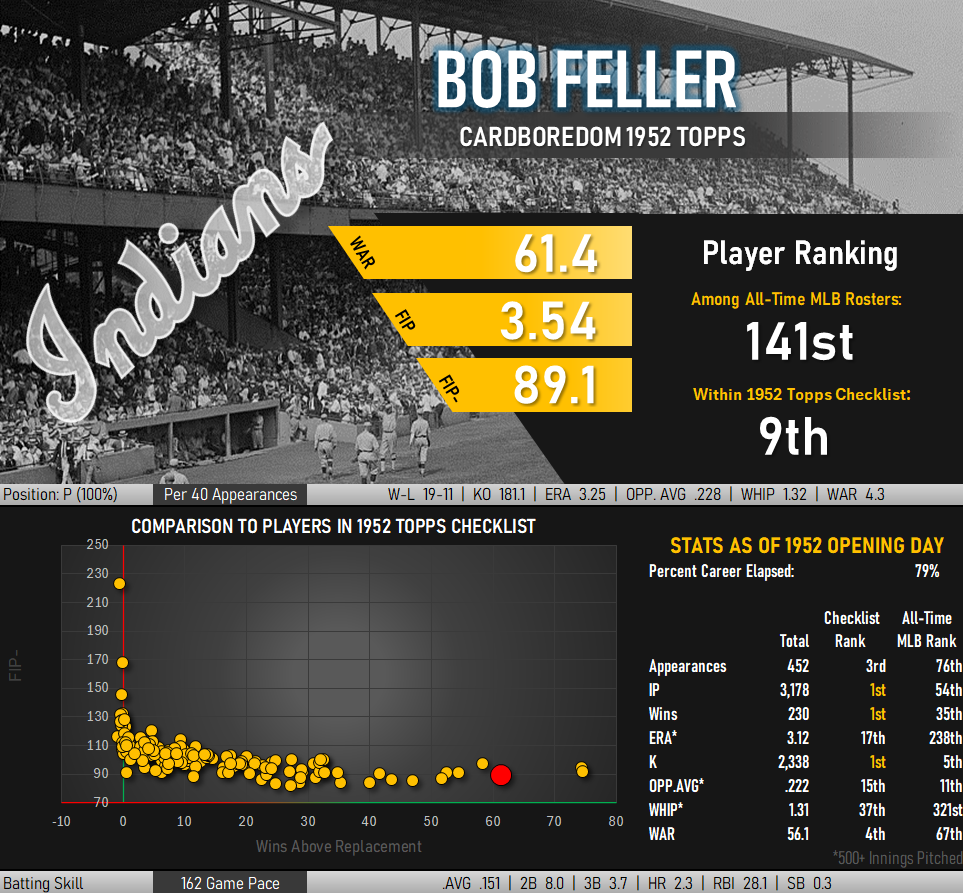

Feller put up impressive career numbers, but they don’t tell the extent to which he dominated baseball in the 1930s and 1940s. He pitched more than a quarter of his career innings before reaching age 22, where he won more than 100 games and struck out batters at a rate nearly 50% higher than his career average. He generated WAR of 10.0 in a single season, an incredible feat for a pitcher.

His career totals omit a significant stretch of time due to WWII service with the US Navy. Feller heard reports of the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor and volunteered 48 hours later. He was initially given an instructor job but requested a transfer to a more forward facing position. The request was granted and he ended up earning eight battle stars with his crewmates on the USS Alabama.

Feller’s fastball lost some speed after an arm injury in 1947. Though he would lead the league in strikeouts a few more times, he was no longer head and shoulders above the rest of the American League. Control issues persisted and he spent the next nine seasons watering down his stats with more pedestrian numbers (Ken Griffey, Jr. or Albert Pujols, anyone?). Regardless, a legend is still a legend and he joined Jackie Robinson in 1962 in becoming the first first-ballot Hall of Fame inductees since the inaguaral 1936 class.

Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio, the greatest offensive forces of the era, both labeled Feller as the greatest pitcher they ever faced.

Kinsella’s book touches on several themes, one of which is baseball’s position as a bridge to the past. Feller’s career arc served as just such a bridge between pre-war and post-war baseball. He met Walter Johnson, potentially Feller’s hardest throwing predecessor. He was in regular conversation with Cy Young until the latter’s death in 1956. He helped lead the precursor to today’s players’ association and focused on providing pensions for retired players, an issue that had reduced Cy Young to a rather low standard of living. He regularly toured with Satchell Paige when the sport was segregated and played alongside him as a teammate when he joined the Indians. When Babe Ruth returned to Yankee Stadium to give his farewell address to fans at Babe Ruth Day in 1947, it was Feller’s personal bat that the Bambino was leaning against for support. Feller claimed to practice pitching almost daily until his 80s. He last played in an exhibition game when he took the mound at age 90 in the annual Hall of Fame game.

Further Reading:

BaseballEgg has a great series of Bob Feller trivia to get lost in.