The New York Giants famously employed an elaborate sign stealing scheme to come from 17 games behind and steal the 1951 National League pennant out from the grasp of the Brooklyn Dodgers. I’m not about to argue against that, but before too much head shaking takes place I want to point out that perhaps the Giants should not have been so far behind to begin with. What made the Giants of the 1950s so interesting is that they were employing strategies 50 years ahead of their time, doing so in a manner that would become synonymous with a club with which the Giants would eventually share a West Coast metro area.

The 1951 team was filled with stars, and it doesn’t take a sabermatrician to appreciate the contributions of names like Willie Mays and Monte Irvin. Still, the SABR crowd could very well stand back and applaud some of the characteristics that were shared through much of the lineup. Take for example the sampling of Irvin, Eddie Stanky, Hank Thompson, and Wes Westrum. What do these names have in common? They each had an on base percentage of at least 100 points greater than their batting average. That is not something you see every day, especially in an era prior to teams keeping statisticians on the payroll. Even in 2024 there were only 8 qualified players who generated such a favorable differential. The ’51 Giants had 4 such hitters in the lineup and at least two more backups sporting similar numbers.

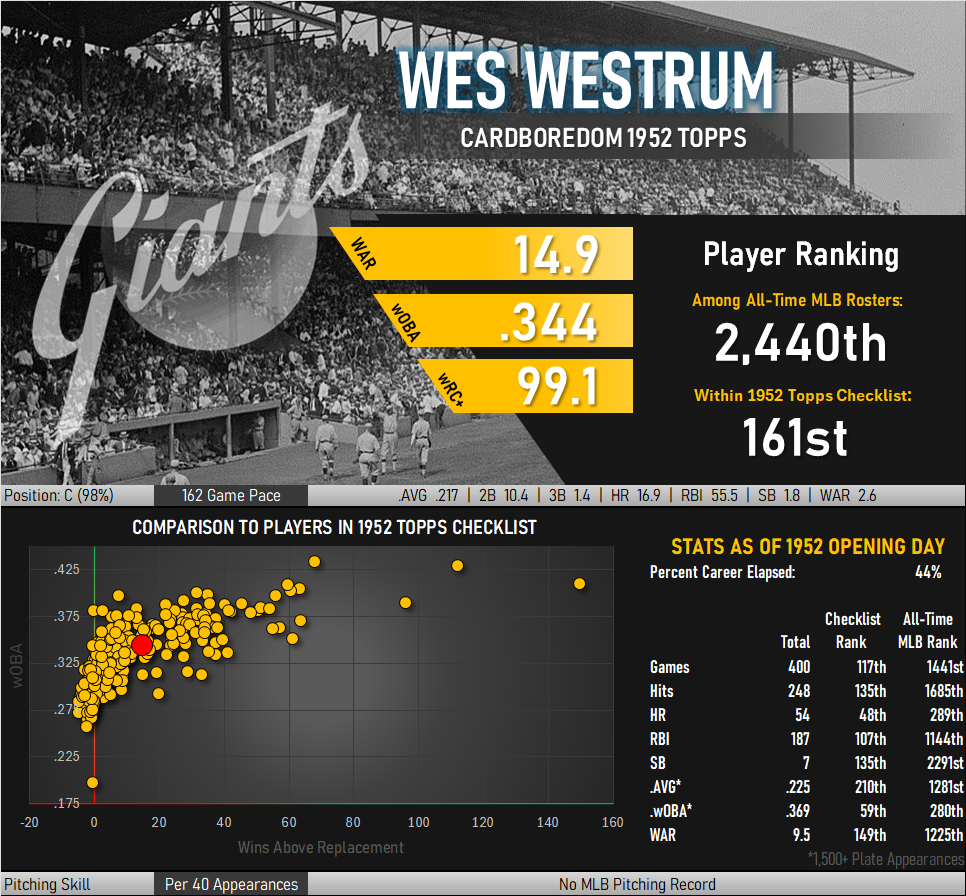

Wes Westrum presents the most interesting of these Durochermen OBP machines. He was known to fans of the team as an incredibly good defensive catcher, someone who was rivaled only by the crosstown arm of Roy Campanella in throwing out would-be base thieves. He tied Willie Mays with 20 on the ’51 home run charts, but his career .217 batting average doomed conversations about his contributions to discussions of his impact on the defensive end of the game.

What should have merited some mention is the oddity of a .217 hitter drawing more than 100 walks in a season. What should have added to the conversation is the fact that when pitchers did decide to throw strikes to this .217 hitter he knocked them out of the park at a clip of 1 home run every 24 at-bats, a better rate than Gary Carter, Monte Irvin, or Will Clark. He would even generate better meaningless stats like RBIs per career hit than Mickey Mantle.

Helping Westrum generate these numbers was a fantastic walk rate of 17.2%, good enough to still rank in the sport’s all-time top 20. If expressed in the familiar form of batting average, his .172 career “walking average” is very close to his .217 lifetime batting average. The differential is 45 batting points, the third lowest among everyone who ever stepped to the plate at least 1,000 times. The only two ahead of him, Red Faber and Mickey Lolich, were both pitchers who saw walks as the only way they could hope to reach a base. The closest modern match to Westrum would be Joey Gallo with his .194 career average and 14.8% walk rate, though an observer would have to see Gallo raise his batting average, take more walks, AND be an all-star level defensive catcher.

It is no wonder that Westrum is the catcher pictured on the cover of the first issue of Sports Illustrated.

There’s No Crying in Baseball (Maybe)

Defensive minded catchers tend to be lauded as field generals, and those who garner that sort of accolade tend to quickly find themselves progressing up the ranks of major league coaching staffs. Such was Westrum’s case, who was asked to direct traffic on the west coast as the Giants first base coach after hanging up his mitt.

As the New York Mets cast about in the early 1960s for throwbacks to better days of New York baseball, they assembled a series of former New York sports icons at all levels of their playing and coaching rosters. Westrum signed on with the team, joining the likes of Casey Stengel and Yogi Berra. The 75-year-old Stengel broke his hip getting out of a car in mid-1965 and named Westrum as his immediate replacement in skippering the club.

There can be quite a gulf between the role of coach and big league manager, one that Westrum was acutely aware of given the reputation of his predecessor and the sudden nature of his promotion to filling out the lineup card. New York, a city famous for letting its athletes know it feels about them, still saw Stengel as the architect of 10 pennant wins rather than the man who led the Mets to three consecutive last place finishes.

The final months of 1965 were tough. After losing games Westrum would consult with Stengel by telephone before facing a room of reporters hoping for a new spin on what was becoming a recurring story. The Mets simply couldn’t win and Westrum was expected to project optimism through his “power of positive thinking” style of management. More than once he choked up and became emotional after late inning collapses.

I guess he figured it out. Aside from quickly perfecting Stengel’s “hand at mouth” manager pose, Westrum guided the Mets the following year to their first non-last place finish in team history. The former bullpen coach also put a young player named Nolan Ryan into a couple of games at the end of the year.

A Whole Lot of Baseball Cards

Wes Westrum the baseball player was interesting, as was Wes Westrum the manager. Even more so was Wes Westrum the litigant. The Giants backstop appears to have been pretty well versed in the finer points of the legal concept of a person’s right to publicity. Few precedents existed regarding the commercialization of one’s right of publicity and it would be a series of cases centering on baseball cards that would set in motion much of what we take for granted today.

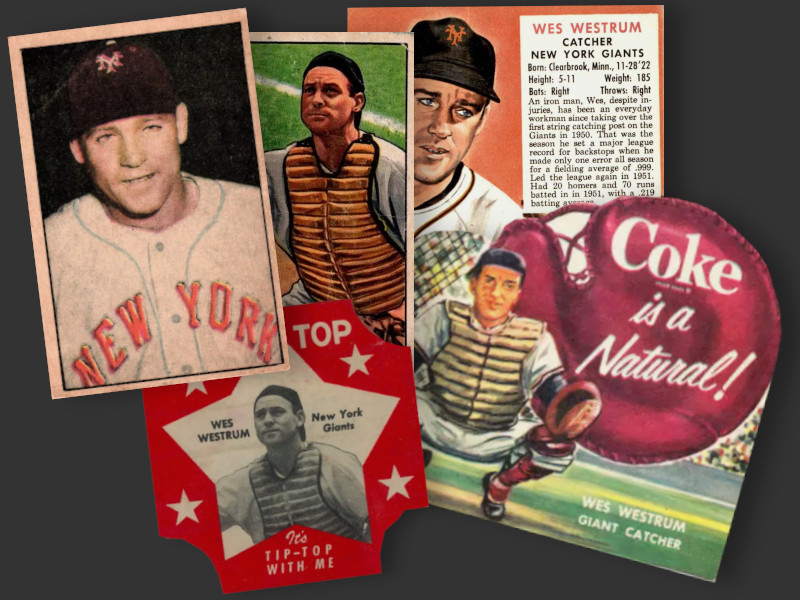

Athletes were often approached by firms looking to market players’ images in connection with printed advertisements. Marketing agents would obtain player consent to appear on an item such as a baseball card in exchange for compensation. The payment could be a higher amount if the player signed off on making this an exclusive arrangement, agreeing to forgo any similar accord for rival products.

Westrum drove a hard bargain, opting for exclusive agreements and the higher paycheck whenever possible. Sports Illustrated documented his 1951-52 signing spree during coverage of the long running legal skirmishes between Topps and the corporate parent of Bowman. Westrum received a wristwatch in 1950 in exchange for granting Bowman exclusive use of his likeness for the following two years. Within a week he had signed the same deal with a licensing entity working on behalf of Topps and another with Russell Publishing Company. For his part, Westrum overlooked his signing multiple exclusive agreements while telling a courtroom that Topps was not to be trusted because they were late in sending him a $150 check.

Setting aside that bit of mental gymnastics, Westrum was indeed willing to go to court over the use of his likeness. He is mentioned in an August 1952 Associated Press story as one of 7 New York Giants (all but one are in the ’52 Topps checklist) to sue firms connected with the distribution of Berk Ross baseball cards for using their pictures without their consent.

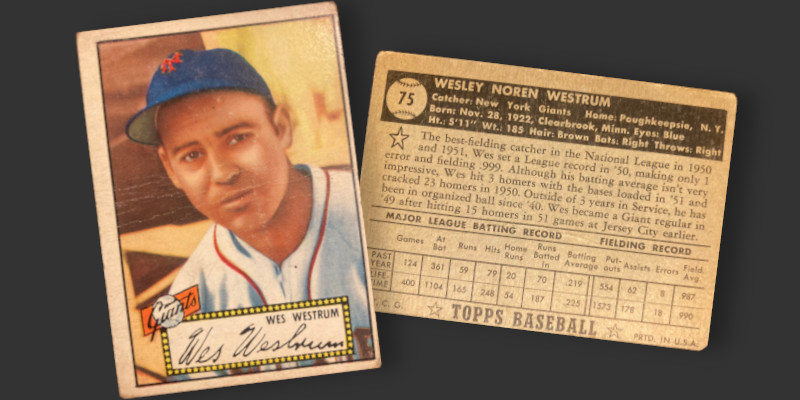

Wes Westrum in 1952 Topps

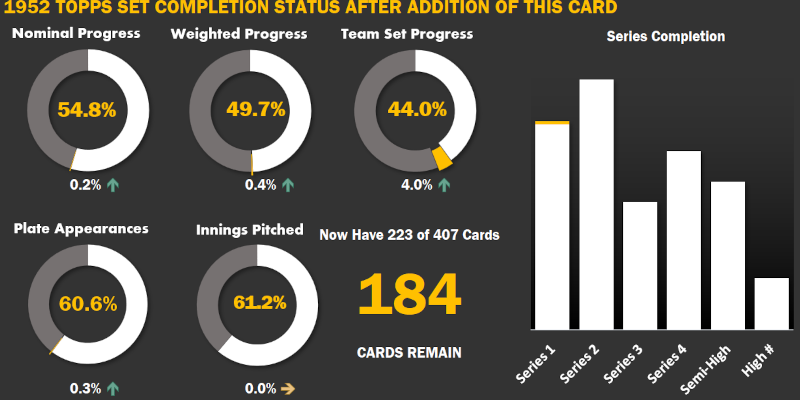

Given the number of early 1950s sets in which he appeared, I have probably flipped past a good number of Westrum cards at card shows. Being focused on building a complete set of ’52 Topps, this is the only one that caught my eye and left a show to join the collection. I really like the red, white, and blue effect of the color treatment applied to the photo.

This example is one of the black back variations contained in the first shipments of Topps’ 1952 release. The color block with a black background draws the eye and his full name appears in all caps. Well, not quite a full name. Collectors may already be wondering how his parents could bestow a name as repetitive as “Wesley Westrum.” It turns out that his middle name, given on the card as “Noren,” was actually “Noreen.” He’s playing baseball with a girl’s name! Don’t let the kids from The Sandlot find out.

Of course, this card was issued in 1952 and featured one of the core components of the pennant winning New York Giants. He would be a National League All-Star in 1952 and again the following season. Nobody was making fun of Westrum, even if the stat line on the card said he batted .219. Yes, that’s a Joey Gallo-esque batting average, but the Giants backstop backed that up by hitting 20 longballs in 1951, twice Gallo’s 2024 total. Even more impressive is that the card indicates Westrum drove in 70 runs despite batting only 361 times. He was generally a back of the order batter and batted 8th in more than half his 1951 contests. That’s a lot of production from the back end of the lineup.

Fun Fact: Westrum played professional baseball while he was high school.