If you find yourself in the top 1% of your profession, you are almost certainly doing well in your chosen field. Indeed, being ranked in the top 5% likely indicates a similar measure of skill. The top 10, 20, or even 50th percentile may imply some level of success. This does not quite hold true in baseball. The distribution of playing success is non-normal, skewing heavily to one tail.

There is usually a basic level of competence associated with making one’s way onto a MLB roster. You’ve got to be good, or at least related to the Washington Senators ownership group to get a shot. That said, baseball chews up players and spits them out. Those that don’t produce play for a few weeks and are replaced. The cycle continues until someone with staying power is discovered. We think of a “normal” career as lasting a decade or more, but that is only because those are the players that excel for long enough to allow fans to even remember their names. The vast majority of players never stick around long enough.

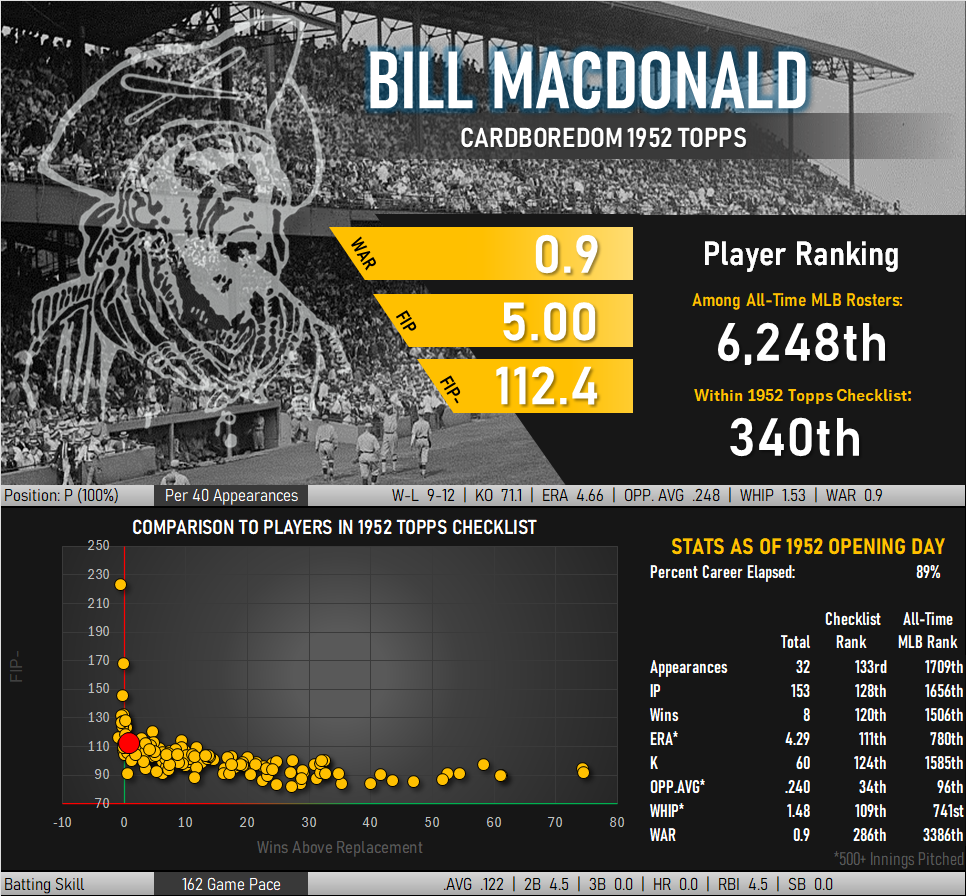

Bill MacDonald was one of those replaceable players. A pitcher with less than a single career win above replacement, he exhibited below average nominal and adjusted fielding independent metrics. A pair of rookie shutouts helped offset a debut season in which he otherwise averaged nearly 5 earned runs per 9 innings pitched. He followed this with several years of military service and returned for another 7 innings of work in 1953. This marked the totality of his career, a comeback abbreviated by opposing batters collectively hitting .400 against him.

Still, that is good enough to rank by my counting 6,248th among all players in MLB history. That leaves another 30,000+ names who wish their careers had gone as well as MacDonald’s did.

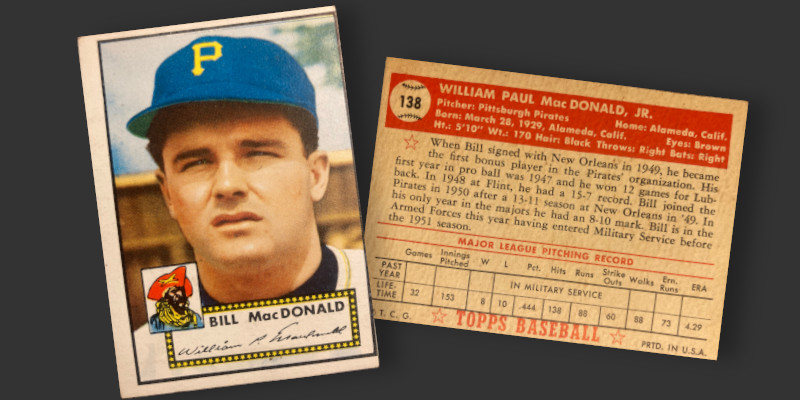

Those early shutouts must have garnered at least a few fans who awaited his return to civilian life. Bowman depicted him in a pitching follow-through against the backdrop of a wooden fence in the gum manufacturer’s 1951 checklist. The back of the card mentions that MacDonald is the first bonus player to play for the Pirates’ organization. Topps followed suit in 1952, opting for a closely cropped portrait against the same fence and leading off the biographical text with the same bonus-themed factoid.

This particular example joined my collection as a Chantilly card show pickup in 2023. The front of the card is very much miscut, but regains a modicum of eye appeal via some of the more vivid coloring among the ’52s in my collection.