Do you remember the 1993 film Rookie of the Year? It is a comedy in which 12-year old Henry Rowengartner suffers an arm injury, only to have it heal in a manner allowing him to throw a 100 mph fastball and get signed by the Cubs.

I recently watched the movie with my own kids, spending much of the time trying to mentally work out what Rowengartner’s stats would have looked like. He strikes out Barry Bonds, indicating he has to be pretty good. Rowengartner only plays a partial season, joining the club when they have already all but given up on the year. He is a reliever and we’re only given insight into 5 innings of work. From this incomplete sample size I come up with a 1.80 ERA, 0.80 WHIP, and a K/9 rate of 21.6. Apparently he could grow up to become Kerry Wood.

We’re only given the highlights and I assume this is not a truly representative sample of how his season went. I was surprised at the numbers that did emerge from my impromptu score sheet, as outside of a handful of throws, Rowengartner has a great deal of difficulty controlling his pitches. His catcher should be the real MVP. Still, as long as the young pitcher is at least facing the right direction on the mound the story will move forward, even if his margin for error is +/- 3 feet from where he aims the ball.

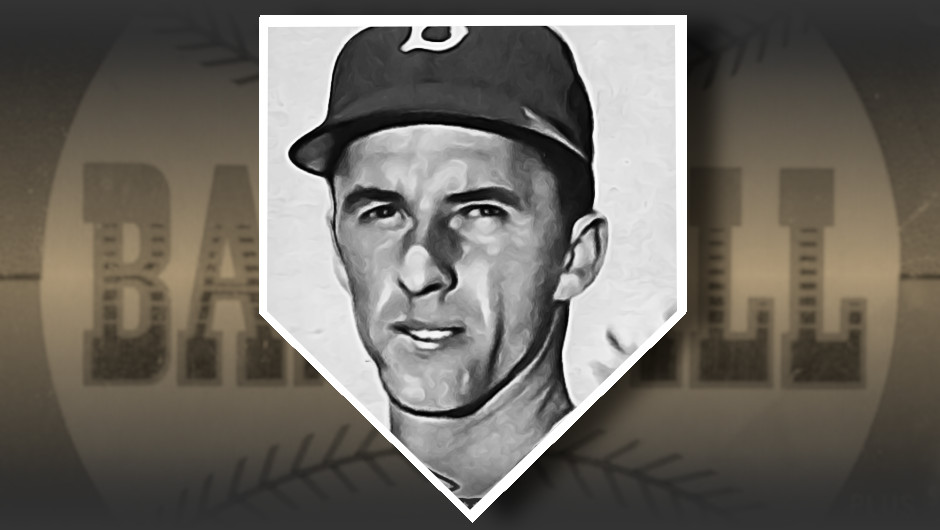

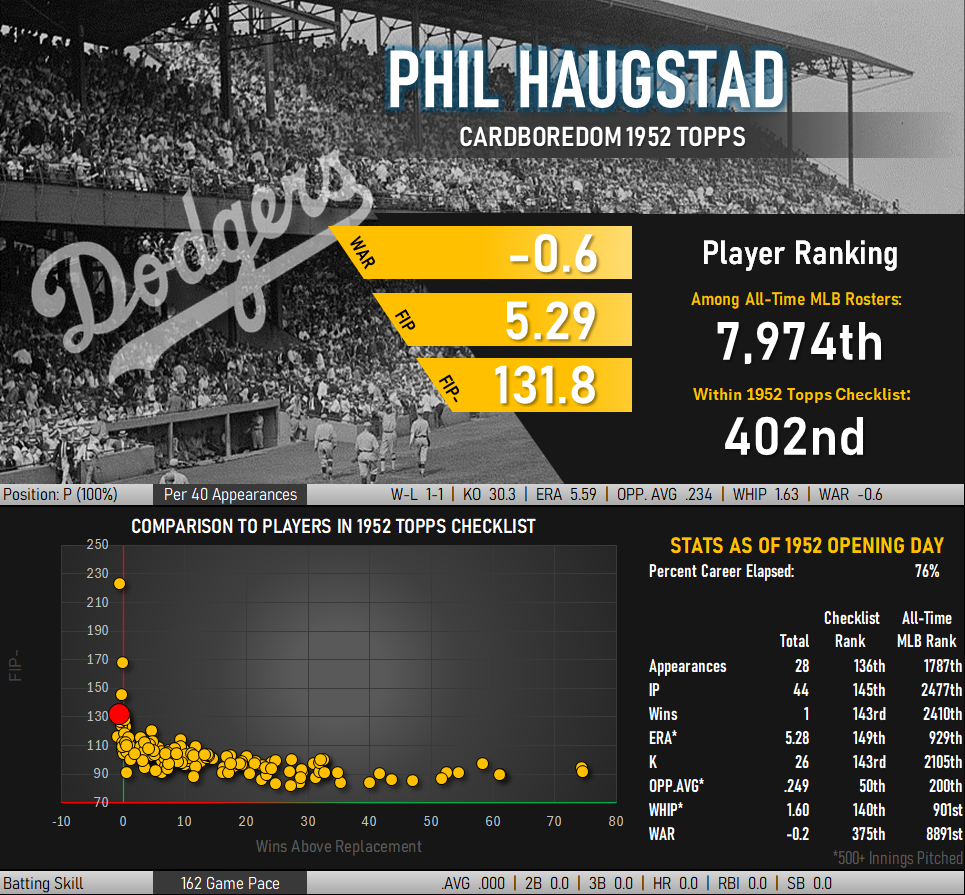

Some time later I was flipping through my 1952 baseball cards and came across Phil Haugstad, a player with a decidedly similar pitching style. Like the little leaguer turned big leaguer, this pitcher was used almost exclusively as a reliever. He had exceptional speed on his pitches, blowing them past opponents on his way to a strikeout title and 22 wins in a 1949 minor league assignment in St. Paul. This led to a few cups of coffee with Brooklyn and eventually a larger but still limited role in the 1951 Dodger bullpen. In the majors he struck out more than 10% of the batters he faced, aided by a sharp whipping motion from long arms on a tall frame. You could almost hear his tendons stretching like a longbow during his windup.

The reason for this hesitation to put Haugstad into the games of a contending team bore some similarities to the fictitious Cubs reliever. He hit 1 out of every 65 batters he faced – about 3x as often as headhunters like Sal “The Barber” Maglie. Walks came almost every inning. He also gave up home runs with some regularity, surrendering longballs almost 50% more often than the average hurler of 1951. Phrases such as “violent” and “wicked” often accompanied descriptions of his pitching motion, giving some sense of the intensity with which these seemingly randomly placed pitches would arrive in the general neighborhood of the plate.

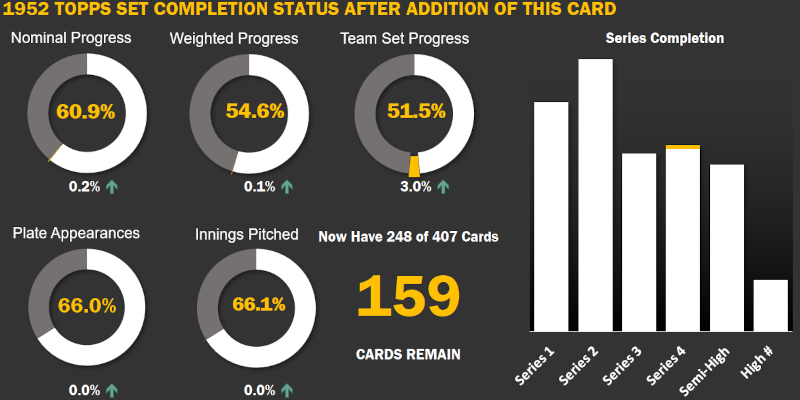

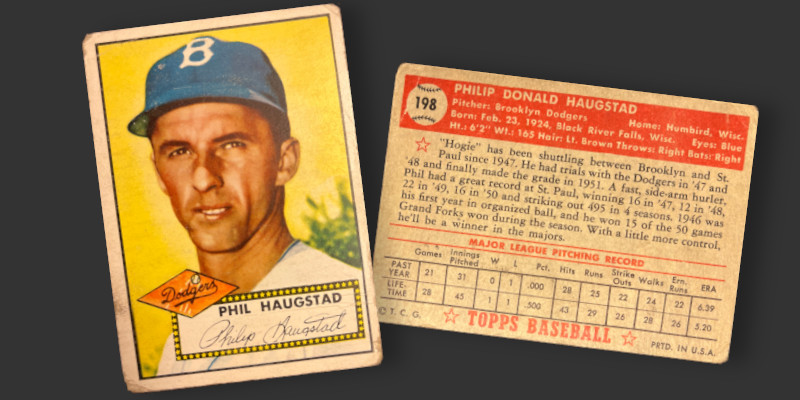

Playing for the ’51 Dodgers was more or less the closest thing he had to a full season in the majors. A sportswriter covering the club’s Spring Training that year described Haugstad as one of the team’s “question mark” pitchers. By the end of the next year his pitching style was considered too wild for the major leagues. Brooklyn-based Topps depicted him as a Dodger pitcher in the fourth series of its 1952 baseball card release, though by this point he had already been dropped from the team, picked up by the Reds, released again after posting a 6.75 ERA, and signed to a minor league contract in the Browns’ organization.

The biographical text on the back of his card wraps up with the insight that “with a little more control, he’ll be a winner in the majors.” Haugstad had already picked up a victory in a 1947 relief appearance, but that would prove to be the only time his name appeared in the win column. This was also his sole playing days appearance on a big league baseball card.

Looking back on the careers of his former teammates for Steve Jacobson’s newspaper column in 1968, Gil Hodges had this to say about the tall guy known as “Hogie:”

“Did a good job one year. Had a real good arm, but had trouble winning. Great pitcher at St. Paul.”