Twenty years ago an event happened that became one of the most famous moments in baseball history. An eager Chicago Cubs fan saw his dream coming true: A foul ball was heading directly towards him as his beloved team was just outs away from finally going to the World Series. The fan grabbed for the ball, unaware that the Cubs left fielder had a chance to nab the ball and move Chicago within four outs of a shot at the title.

Moises Alou had the closest view of what transpired and only had one word to describe it. It was a verb, but not really. His utterance could have been a noun, but he wasn’t really calling the Cubs fan a name. It could have been modified into an adjective, but there was nothing else being said that could be modified by it. It was just frustration, sadness, and a sense of losing something he thought was already his all rolled into one syllable.

The left fielder raised his arms to steady himself after coming down from his leap and transitioned the pose to one asking why this had happened. He slammed his arms towards the ground, seemingly wanting to throw his glove down, and said F#@$ to the left field foul line. He punched the air with a restless arm, and repeated the word with more emphasis. Turning away from the fans, he shouted it.

When play resumed, Cubs pitcher Mark Prior threw a passed ball that allowed the baserunner on second to advance. I don’t know if Alou said anything about this, but with each additional play of the famous Cubs’ collapse unfolding there was heard a collective “F***!” rumbling from fans across Chicago.

That is the moment I remember Moises Alou for. I can’t see him in any other context, just the 21st century equivalent of Andy Pafko watching Bobby Thomson’s home run sail over the Polo Grounds fence.

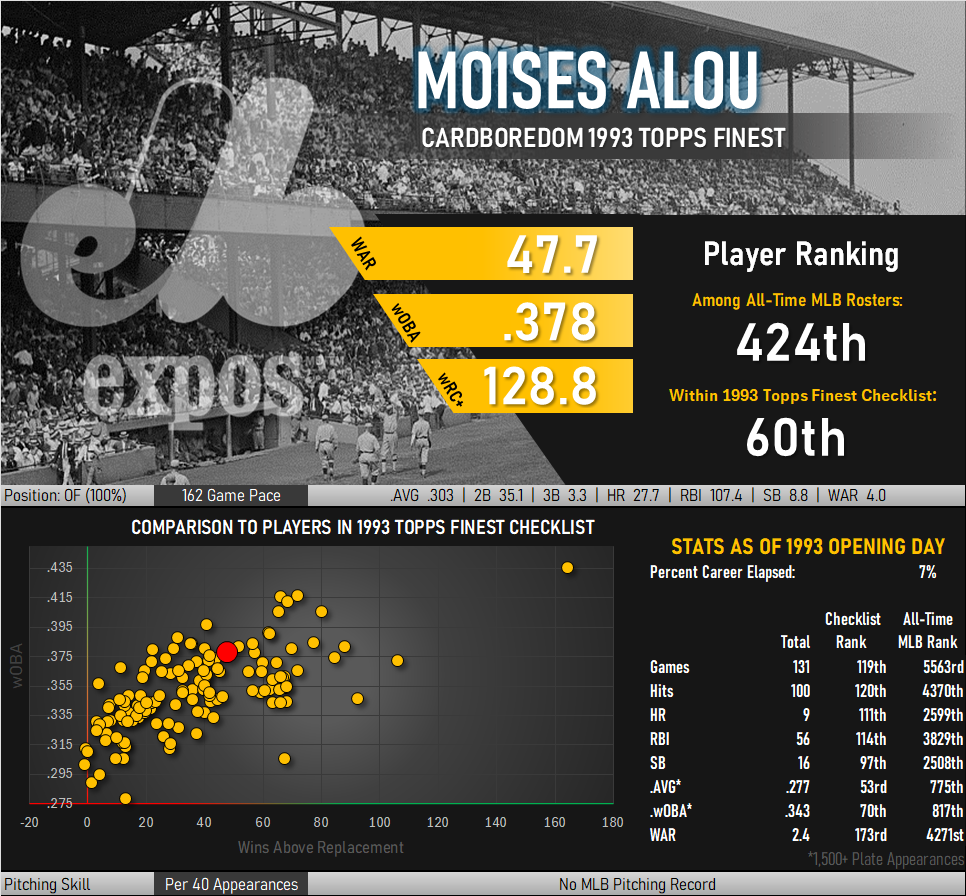

That’s amazing, as Alou was actually a pretty special ballplayer. Looking at my scatterplot of those appearing in the 1993 Finest checklist, he inhabits the no-man’s land between the game’s all-time top 1% and the Hall of Pretty Good. Transport his stat lines back to the 1920s and the sport’s Veterans’ Committees would have shoveled him into Cooperstown along with along with the era’s other players showing above average skill. He finished his career with a batting average north of .300, hit well over 300 home runs, and drove in more runs than Gil Hodges, Hank Greenberg, and Will Clark.

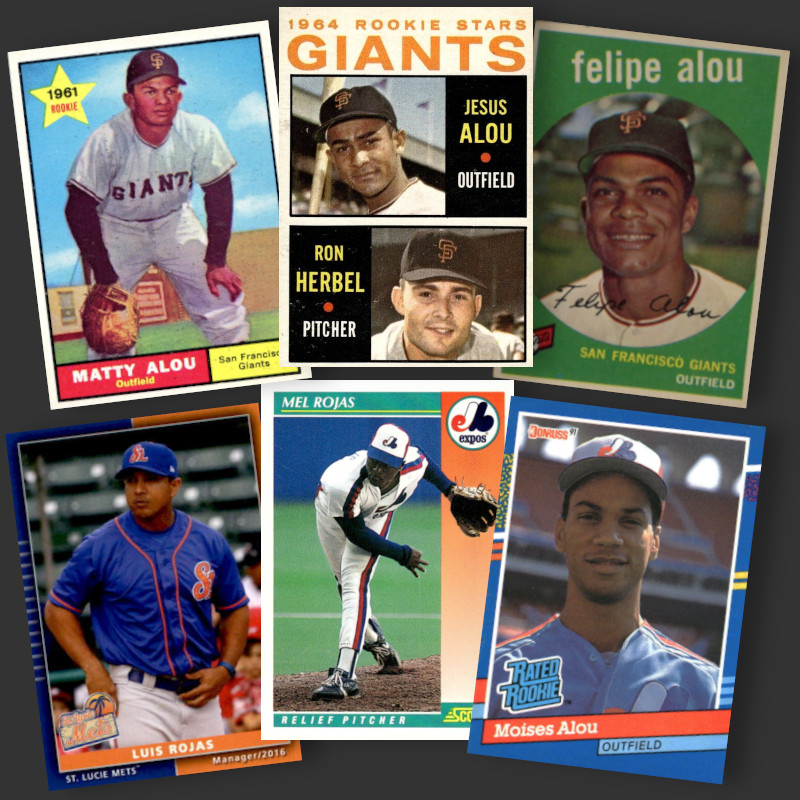

Moises may very well be the best among an entire family of MLB players. His father, Felipe, was a longtime outfielder with the San Francisco Giants who put up near 40 career WAR. Felipe’s brothers, Matty and Jesus, soon joined him in the 1960s and at one time formed the first all-sibling outfield. Luis Rojas, another son of Felipe, played professional baseball and eventually managed the New York Mets for a couple seasons. A cousin, Mel Rojas, pitched for the Expos in the 1990s.

Moises is the only Alou representative in the 1993 Finest set. The best thing about this card is the fact that you can clearly see his hands as he drops a bat and begins running out a hit. His hands are bare with no trace of a batting glove. He never used them and stood apart from other players in this approach. I’ve never understood why a player would use them, but it seems to be taken as gospel by the rest of the sport that this piece of equipment is essential for the playing the game.

So why do players use batting gloves? It is said they improve grip, though there doesn’t seem to be a history of many bats flying back towards the pitchers mound in pre-glove eras. Those wanting a more tactile experience may do better by just putting tape or pine tar on the bat handle. Gloves reduce “bee-stings” from the vibrations emanating from a bat making contact with a ball. Didn’t those stop bothering players sometime after transitioning away from playing T-Ball? Some say they keep hands warm in cold games, but as anyone who has accidentally donned batting gloves instead of real gloves can attest, their effectiveness in this regard is almost nil. Batters sometimes say this keeps blisters and calluses from forming. Anyone who spends time in a gym already has a nice protective coating of calloused skin, indicating soft-handed major leaguers might be better served by hitting the weight room. I’ll get off my soapbox now, but not before admitting there is something refreshing about Moises not needing time between pitches to adjust velcro glove straps.

I think Moises distilled a lot of what is really necessary to play the game and focused his attention there. That is the kind of ethos and focus on the fundamentals that gets instilled in a young player who grows up surrounded by excellent players.