How do you solve a puzzle when you don’t even know what it looks like?

There’s something to be said for making a challenge even more challenging. Crossword puzzles were something I followed in newspapers as a kid, and one particular kind was especially fascinating: Diagramless Puzzles. These puzzles are just like the normal black and white grids inhabiting the paper, but with a key twist: They’re blank. To solve one, you must fill in the answers to the clues without knowing where the black squares are, the length of the words, or the location of any of the numbers corresponding to the clues. Getting an answer wrong not only disrupts your ability to answer adjacent clues, it fundamentally wrecks the shape of the puzzle, throwing off all subsequent answers. Good luck answering 15 Across if you don’t know where that even is.

That said, this mashup of a traditional crossword puzzle with blindfolded chess is not impossible. There is usually some sort of structure to the grid construction, often in the form of symmetry in the placement of black squares or minimum word lengths. A common theme also unifies the words, further helping narrow the possibilities. They are doable (here’s a sample), albeit in a much more time intensive effort. These puzzles are polarizing. You are either drawn to this sort of challenge or immediately repelled by it.

Kind of like early Leaf baseball cards.

Attention Grabbing Cardboard

My introduction to word puzzles came through a brightly colored gateway: Newspaper comics. Growing up in the late 1980s, our local newspaper published its Sunday edition in color. At some point between first and second grade, I caught sight of the paper’s comic section. Cartoons! Color! Jokes! I became a daily newspaper reader at that point, progressing from comics to sports to world news before my interest in baseball cards even began. During this progression I began to notice the word puzzles occupying the real estate next to the comics.

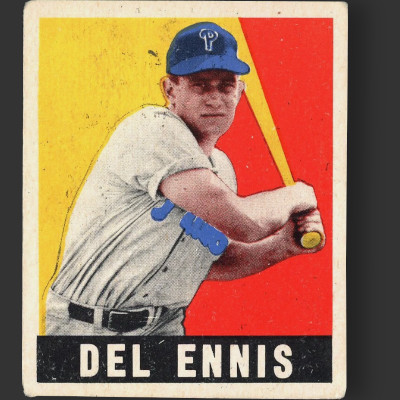

Bright colors, the distinctive smell of off-gassing ink, and the whiff of a lurking challenge made the morning paper memorable. So would the flash of vivid color block patterns amid otherwise muted vintage cards and the smell of old cardboard in rented hotel ballrooms, and the hint of something unattainable gleaned from the $10 stickers adorning sleeved commons. Baseball cards from the ’49 Leaf set. Their haphazard print quality even resembled something rolling off the presses with the Sunday news.

Those higher price tags kept me away from these cards as a young collector, even if Del “Ennis the Menace” had a name calling to mind a comic strip. The memory of the cards was still present when I returned to the hobby decades later, prompting me to pick up a common from the checklist as a type card. Thinking the itch had been scratched, I thought nothing more about it. That is, until I came across an interview with a graphic artist named Karl Dykstra.

The Dykstra Interview

I collect baseball cards and my wife collects master’s degrees. I’ve seen enough of her research to get a firm handle on the importance of primary sources. To understate it: Primary sources are an incredibly big deal. Everything else is just derivative.

When seeking out audio for car rides I came across the back catalog of Jim Beckett’s podcast Sports Card Insights. I loaded up a few dozen episodes promising to touch on areas of my collecting interests and took off. One of those was Episode 342, which promised a discussion of 1949 Leaf baseball cards.

Now, to those who consume a lot of hobby media, a typical look at ’49 Leaf usually involves a host sounding surprised about the basic facts of the set. There are short prints? Leaf was sued by Bowman? The cards were issued in 1949? Wow! So insightful! There’s not a lot of new ground covered in these basic overviews. Not having read the program notes, I wasn’t expecting much. Perhaps a discussion of printing techniques if I was lucky.

Here’s the hook: Dr. Beckett mentions that Dykstra’s father built a first series set of these cards from wax packs in 1949, and documented the process via a personal journal in real time. I was listening intently. The conversation went back and forth, with Beckett painting a picture of a set that didn’t seem to gain any sort of consensus about its contents until the 1970s. He said he was unaware of anyone completing the whole thing until the middle of that decade.

I had known about the internal hobby conflict over determining what year these cards were issued, and that there had been ample speculation about the causes of the checklist’s numerous short prints. What hit home for me was the amount of time that passed since 1949 for a consensus to form over exactly what constituted a full set of cards. This wasn’t an obscure regional issue. Wasn’t there a Standard American Card Catalog that listed all known cards? Wasn’t the first set showing up fully listed in the price guide arriving each month in my childhood mailbox? Weren’t there people like Dykstra’s father that remembered opening packs just a few decades earlier? This wasn’t ancient history. I can tell you today about packs of Donruss I opened in 1991. It would seem like someone in the 1980s could have been able to do that regarding memories of ’49 Leaf.

Taking a step back, what fell into place like the answer to a crossword clue was this: The dimensions of the 1949 Leaf set were largely unknown at the time of their issuance, and collectors intent of completing this seemingly unsolvable puzzle needed to not only piece together the checklist but the rules governing its construction. The puzzle had layers, and it would take decades of the hobby’s equivalent of peer review to collaboratively work towards a solution.

Today we have definitive checklists from which I can compare my few dozen names against the 98 in the checklist. To those chasing the cards decades after their introduction, this was both a collecting and mental challenge. The extended timeline and collaborative nature of solving the checklist holds the key to taking this set from a striking visual oddity to one that captures my imagination and made it one of the pillars of the big three sets I collect.

Someone Already Did the Homework

The fact that full checklists have been known since my introduction to collecting is evidence that others already did the hard work of solving the puzzle. The new puzzle for me was determining how they did so. If I were collecting in the 1950s or 1960s, what would I need to do in order to solve the mystery?

Seeing nothing out there in the mass market collecting publications, I turned to the sleuths inhabiting Net54. There, laid out in a detailed post with only a handful of replies, was what I was looking for. David Kathman, a Chicago-area collector going by the pseudonym trdcrdkid, not only laid out the timeline of how the hobby solved the puzzle, he did so while attaching scans from his early hobby library outlining the experience of those who solved it.

A group of enthusiasts dedicated to a set one of them described as “the worst looking” engaged in the early card collecting hobby’s equivalent of the Republic of Letters to understand the ’49 Leaf set. Other collectors hung onto these niche, often mimeographed publications, passing them on to those would appreciate their contents.

Kathman has curated such a collection of these publications, acquiring stacks of material from early dealers and hobby pioneers. For years he shared with other collectors snippets of these back and forth articles and their accompanying calls for information, ultimately leading to the assemblage of a documented timeline of the decoding of the ’49 Leaf checklist.

The Timeline

I recently reached out to this collector to inquire about reproducing his scans for the purposes of fleshing out this timeline. I am providing small excerpts from the images and want to encourage readers to examine the full scans and context provided in the original post. If you like what follows, you’re going to love seeing the full trove.

1949

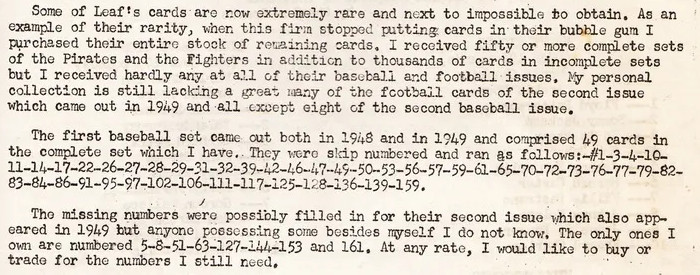

Multiple collectors quickly assembled the first series set. Karl Dykstra’s father and countless numbers of gum chewing kids did it. Lionel Carter and Walter Corson reported completing the set as well. Given previous bouts of skip numbering in the hobby and news of Bowman using the legal system to remove Leaf as a card producing competitor, it was initially assumed these non-consecutive cards comprised the full extent of Leaf’s foray into that year’s baseball card landscape.

1956

The first mention of there being more than 49 names in the checklist came in an issue of Sport Hobbyist. Walter Corson, then recovering from a major health scare, was writing a series of articles in which he discussed his collection and several card issues of note. The curator of one of the largest collections of his era, he notes that he was able to purchase the unsold stock of 1948-1949 Leaf trading cards. Seemingly included in that lot were 8 cards previously unknown to exist. This implied a full set contained at least 57 cards and likely more given card manufacturers’ tendency to release their product in staggered series. Importantly, other well-known hobby figures like Lionel Carter and Buck Barker published contemporary articles in which they describe the set as being limited to only 49 skip-numbered cards. If there was a moment of someone announcing the existence of a larger puzzle, this was it.

1960

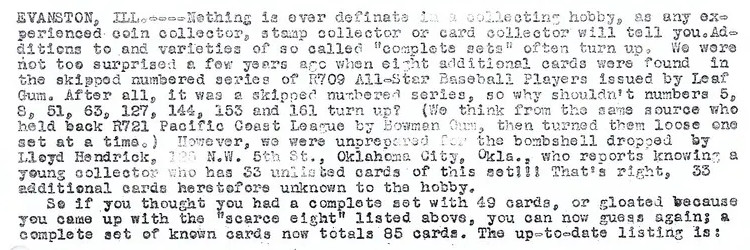

Lionel Carter took note of the newly discovered cards, referring to them as “the scarce eight.” At the outset of 1960 he noted in Sport Fan that he had yet to secure any examples of the newfound numbers for his own collection. The real news, described by Carter as “the bombshell,” was a report by way of Oklahoma City about a collector that not only had the mysterious 8 cards, but another 25 previously unknown to the hobby. Carter reported it as in the excerpt below and followed it with what was at the time the most complete checklist of the issue.

The addition of 25 cards to the expanded 57 name checklist only hinted that more cards existed. Some of the cards reported in the hands of the young collector (later identified as Larry Fritsch) had apparently been run through the printing process backwards, resulting in mismatched backs. These mistaken front/back multiplayer combinations revealed the existence of three additional names, taking the total known checklist size to 85.

1961

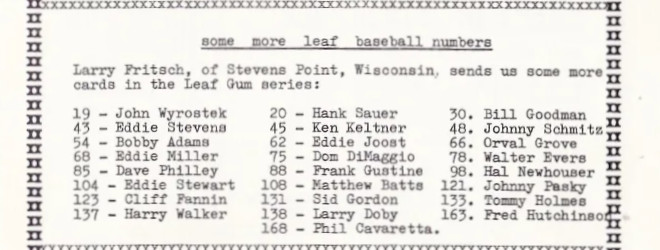

Shortly after Carter’s assessment of the state of the Leaf checklist, Thomas Harden recapped the checklist status for Card Comments. Harden’s analysis was less thorough than Carter’s, but he made up for it with calls for readers to supply him with new card numbers. He seemed to generate a good response, and among those writing in was the aforementioned Larry Fritsch, whose inventory of short prints had modestly changed since Carter’s 1960 report to include a Sid Gordon short-print.

1965

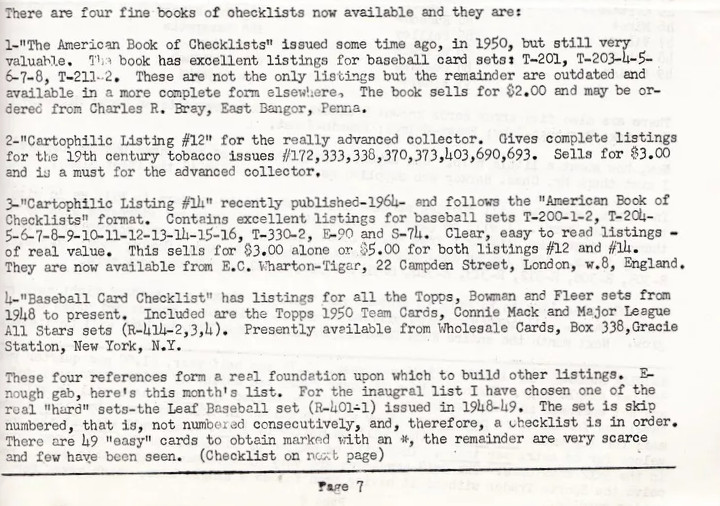

Richard Egan kicked off his “Egan’s Alley” for The Sports Trader with a call to action for collectors to help identify missing cards from checklists of the hobby’s numerous skip or outright unnumbered issues. His inaugural article identifies four reference books as being particularly helpful for collectors but hints that they may be incomplete regarding some of these sets.

Egan then goes on to provide Leaf collectors with the consensus checklist for the set (so far). Of interest is the fact that his checklist, largely sourced from the resources we have already seen, includes the first appearance of the set’s Bob Feller card, bumping the checklist population by one more name. I do not know if this was due to a collector volunteering information or if it was reported by one of the guidebooks called out in his introduction.

Additionally, follow up notes in Egan’s column that year reported the rumored existence of five previously unassigned numbers, though their veracity and affiliations with specific names would not be resolved for several years. The checklist had grown by one but clues were mounting that additional cards were in the offing.

1968

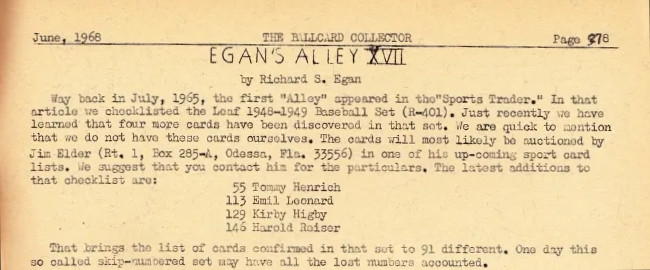

The known checklist expanded by 4 to 91 in 1968. Now writing in The Ballcard Collector, Egan once again visited his earlier accounting of the contents of ’49 Leaf and updated the checklist to incorporate four cards reportedly coming up for auction. 91 cards now could be definitively linked to specific players.

1969

This would be the year that we solved two of mankind’s most intractable problems: How to get to the Moon and learning the full extent of the 1949 Leaf checklist. Egan, writing his Egan’s Alley column for yet another publication (Sports Collectors’ News) once again provided an update on the ’49 Leaf checklist.

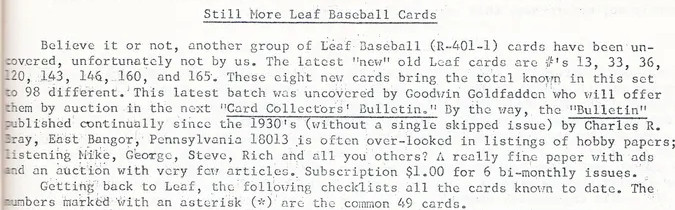

The newly introduced cards expanded the checklist to 98 names and fully addressed the unnamed card numbers referenced at the end of 1965. Two decades after the set was released and just as quickly pulled from the market, collectors had an idea of what constituted a full set. Research would continue into the issue, and hopes simmered for continued expansion of the checklist to fill out all the 70 missing numbers up to 168. Eventually the cards’ enthusiasts would come across an uncut sheet of 49 first series cards. Given the piecemeal discovery and cataloging of a perfectly symmetrical quantity of second series cards, it became apparent that the total number of cards released topped out at 98.

Today we can pick up the Standard Catalog or look at dozens of different websites to get accurate checklists from even the most obscure vintage sets. It’s easy to forget how much research, hard work, and collaborative networking was undertaken in the 1950s and 1960s to figure out that information for the first time.

That same ethos of collaborative learning still thrives in corners of the hobby. As long as collectors like Kathman gather to pass along information on message boards and share the older records of the hobby with future generations, the hobby will be as enjoyable as ever. I might even track down a few baseball cards.