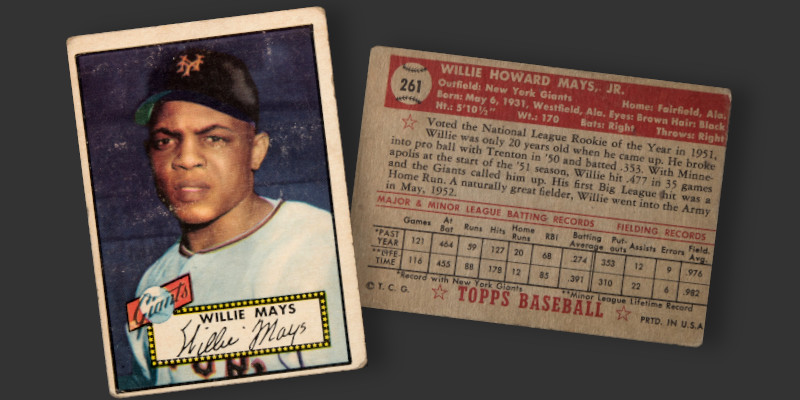

This is my 500th post here at CardBoredom. It’s therefore fitting that the card profiled should be special and this one definitely fits that description.

I returned to collecting baseball cards after a two decade hiatus. When I resumed acquiring cards I set a goal of building a couple of the most outrageous sets out there. One of those, 1952 Topps, was the largest11 produced in the first 90 years of baseball card history. There are multiple factors making completion of a full set extremely challenging, primarily 157 cards across the two final series having been printed in lesser quantities than their lower numbered counterparts. Those 157 cards represent the heart of the challenge and contain within their names four absolute monsters constituting a Mt. Rushmore of grail-worthy cards for collectors to tackle.

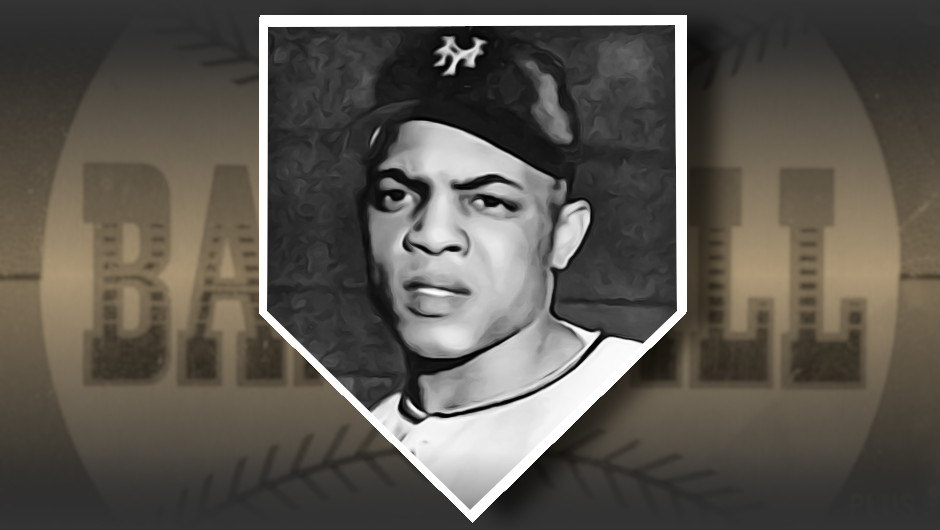

Adding the legendary ’52 Topps Mickey Mantle, the best card ever made of Jackie Robinson, or an Eddie Mathews rookie are undertakings that do not come easy, even if considerable financial factors are not an issue. One needs a touch of madness and the optimism of an A’s fan purchasing postseason tickets to walk into a card show looking to add any of these cards. I have yet to address any of these three names in my quest to complete the set of a hobby lifetime. Instead, this post examines how I came to chase and (twice) land the Topps debut of Willie Mays.

My history with the card goes back about 25 years, roughly at the midpoint of Mays’ last trip to the plate and today. I was somewhere in my first year of college and had largely finished selling off much of what I had collected since age 8. I had a little over $700 in proceeds that wouldn’t be needed for another semester and decided to pursue some part-time baseball card dealing as a way to grow my funds.

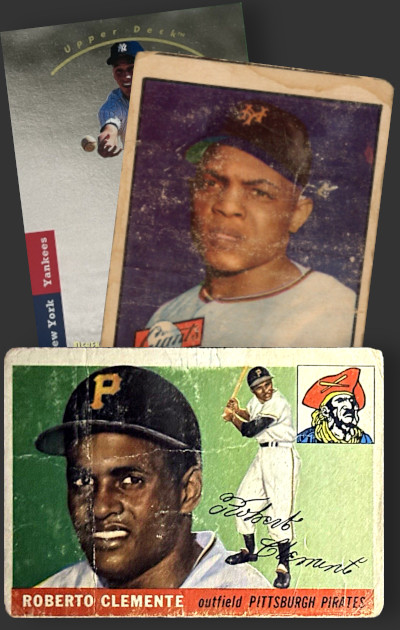

Having just pieced out a collection of more than 10,000 cards, I was in no hurry to repeat the process with $700 worth of dime-box material. I resolved to only focus on bigger ticket items that would have clear demand. This led to the purchase of three cards: A poor condition 1955 Topps Roberto Clemente rookie ($250); a 1993 SP Derek Jeter rookie slabbed as Gem Mint 10 by GEM Grading ($150); and a low grade, stained ’52 Topps Willie Mays ($300). The Clemente rookie soon netted a $50 profit and an earful from a buyer who wanted to argue about how the descriptor “poor” should have been downgraded to “catastrophic.” The Jeter was a financial bust in which I quickly learned the relative value of top tier grading services over their lesser peers.

The Mays more than made up for it. I promoted it on eBay, which at the time meant it would be rotated through the auction site’s main landing page and bumped to the top of the baseball card listings for a $50 fee. The card quickly gained a following and it netted proceeds of more than $500 after accounting for eBay’s cut and promotional expenses. There’s an old cliché about naive hobbyists expecting their cards to pay for someone’s education. To the extent of about $200, this one actually did.

Aside from getting a few textbooks out of the experience, the payoff wasn’t financial. Holding that card was like shaking hands with history. For two decades, it became my definitive answer to two questions: the best card I ever owned and the one I most regretted selling.

Outlier

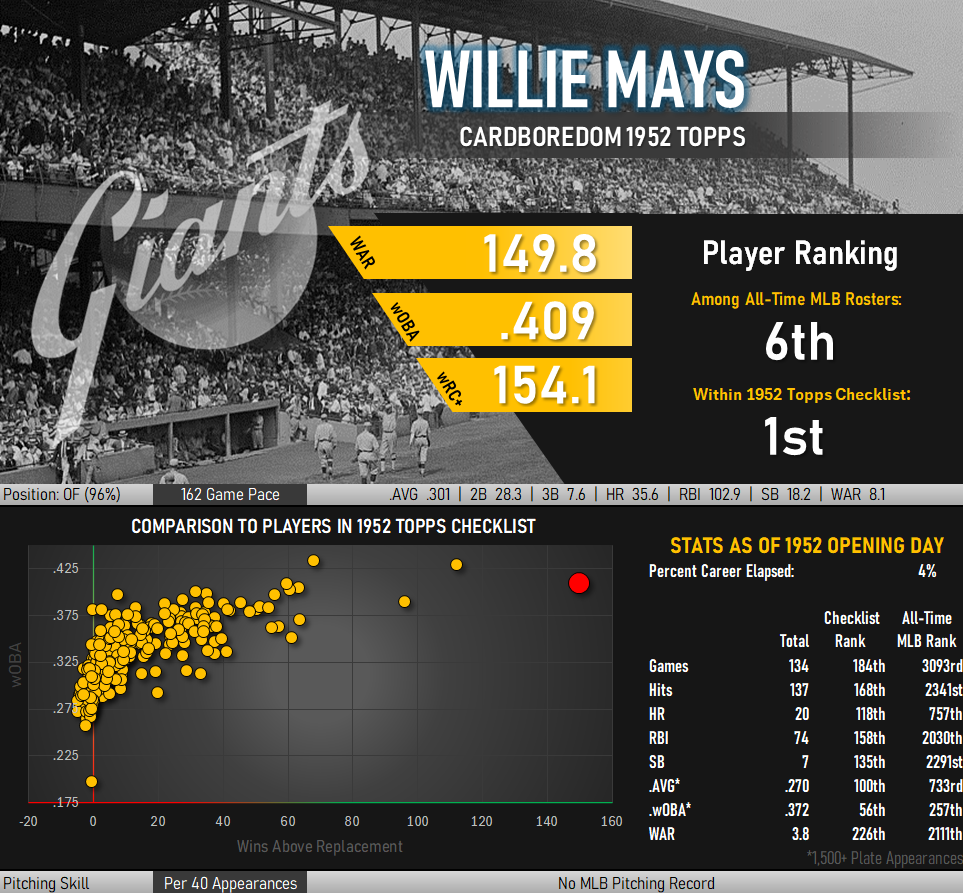

To reiterate why any card of Mays is special, one need only reference the scatter plot below. Almost the entire ’52 Topps checklist is clustered near the left side of the graphic with Cooperstown-worthy talent inhabiting the region near the middle of the X-Axis. Three dots stand apart on the right side, instantly informing the viewer that they are witnessing something special. The second most easterly dot represents the career of Mickey Mantle, but even that pales compared to the enormous gulf separating him from the red dot that is Mays. This is simply a massive output gap. You can add Roger Maris’ career to that of Mantle and still find his dot to the left of Mays. The Giants’ centerfielder was that good.

Given this assessment, it seems a bit incongruous that my personal ranking of all-time greats has Mays as the sixth best player to pick up a ball. And yet, here we are:

| Rank | Name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Babe Ruth |

| 2 | Barry Bonds |

| 3 | Ty Cobb |

| 4 | Ted Williams |

| 5 | Roger Clemens |

| 6 | Willie Mays |

Williams is in the mix from how well his one-dimensional style of play matches up with my preferred view of the game. Bonds and Clemens have their own baggage that has to be dealt with. Cobb’s outperformance largely came inside the alternate dimension that was the Dead Ball Era. Like all all-time rankings, this discussion quickly devolves into a comparison with Ruth.

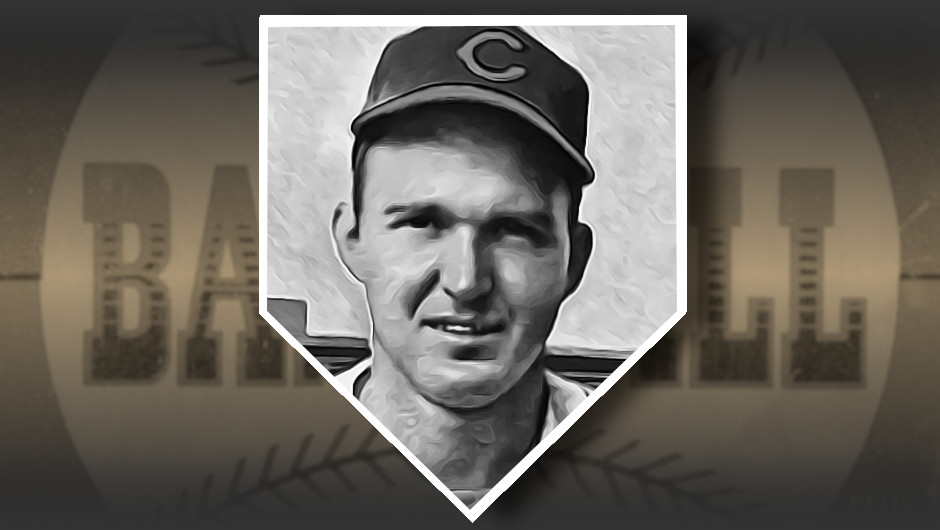

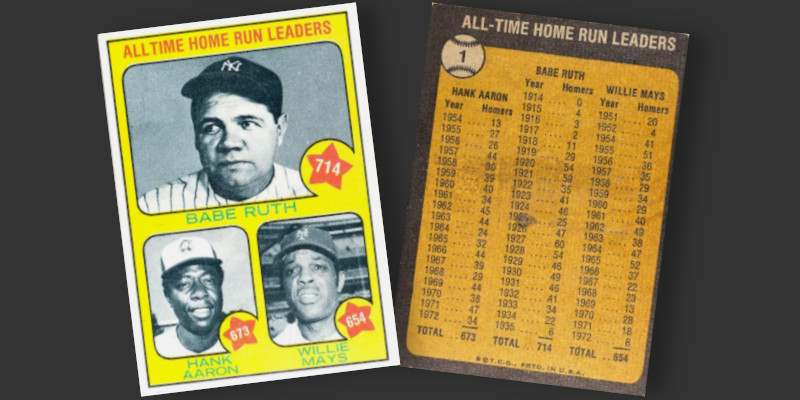

This card2, issued as the first card of the year by Topps in 1973, drives the point home pretty clearly. Already reduced by this point to single digit annual home run totals, it seemed that the books were closing on Mays falling well short of Ruth in any sort of hierarchy of baseball greats. And yet, there is a compelling argument to make that puts them nearly equal.

Just as Topps did at the start of the 1973 set, the first number anyone goes to for Ruth is his 714 home runs. Mays hit 660 longballs, but that difference of 54 homers is not as cut and dry as it would seem. Mays spent almost two full seasons away from New York, perfecting his basket catch on an Army team in my neck of the woods at Fort Eustis while losing as much as 270 games worth of MLB playing time in the process. Prior to his induction into the armed forces he averaged 0.158 home runs per game, implying his career total would have reached a nearly-Ruthian 701 home runs. Mays returned to the Giants in 1954 and promptly hit 0.27 home runs per game, implying his 660 HRs could have been as much as 733 without that time away. Meeting the two rates in the middle produces a number almost exactly equal to Ruth. Without that time in the military Mays may very well have been the all-time home run leader by the time that 1973 card was produced.

The theoretical gulf with Ruth is shrinking and gets even smaller when playing eras are considered. Ruth largely played in the offensively charged early days of the live ball era, a period that saw the average hitter hit well into the .280s while slugging close to .400. Defenses of the time had not yet adjusted to the changes benefitting hitters while the major leagues simultaneously toyed with various iterations of juiced baseballs. Mays, on the other hand, played his career in a period where the average batsman hit 29 points below the prior level at .253.

Baseball was actively promoting the offensive side of the game in the 1920s while it was actively working against hitters in the second decade of Mays’ career. Commissioner Ford Frick infamously adjusted elements of the game to favor pitchers, culminating in supercharged pitching that dominated through 1968’s “Year of the Pitcher.” What would Mays’ numbers have looked like with those missing games and a 30-point tailwind tacked onto his hitting?

Ruth’s most impressive stats are those derived from the immense distance between the Sultan of Swat and typical players of his era. In terms of talent, Ruth, Mays, and Barry Bonds probably rank near the top of what is humanly possible in the game. I think we will add more names to that short list over the next century, but are unlikely to see a Ruth-level outperformance over replacement level players.

The reason is replacement level players have improved dramatically in the time elapsed since Ruth’s era. This shift is driven by improved player development and racial integration. The modern incarnation of minor league baseball was not around during Ruth’s time. The “farm system” of nurturing baseball talent was largely pioneered by the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1940s, eventually paving the way for all teams to have lower level affiliates where players could gain some seasoning without destroying the parent clubs’ chances of winning a major league ballgame. In Ruth’s day, a rookie could have gained experience with semipro teams of varying quality or even come fresh from a local sandlot or American Legion ballfield. The decades following Ruth saw improvements in analytics and strength training, functions that have greatly improved the competitive landscape.

The arrival of Jackie Robinson on the Brooklyn roster in 1947 brought about another step change in player quality. As the sport haltingly lurched through integration, it introduced new players into the mix. With the number of available roster spots remaining the same until the 1960s, the effect of this new influx of talent raised the bar for the minimum level of skill needed to even crack the roster out of Spring Training. Average roster quality improved while the players at the very top of their game found themselves playing against tougher opponents.

Guess what? Baseball doesn’t just recruit from Iowa anymore. Japan, Korea, Mexico, and pretty much anywhere in the Caribbean is a well developed source of incoming players. As the game becomes more international we’re going to see further improvement in that prototypical baseline replacement level player that everyone gets measured against.

Given the extent to which the typical player has improved over the past century, Ruth may be the high water mark in terms of individual outperformance. This makes the relative standing of later players (Barry Bonds in particular) more impressive, further narrowing that divide between Ruth and the rest of the game.

We haven’t even touched Mays’ legendary performance in the outfield and his superb baserunning. Adding his card to my card collection would not only represent the best player in my ’52 set building project, but potentially the entire collection.

Card Show Conversations

By the time I briefly became the owner of a ’52 Mays I had already stopped attending card shows. I didn’t set foot inside another until 2022. When I eventually did so, I was a year into my ongoing attempt to build the 1952 Topps set and keeping an eye out for anything originating from that issue. I came across more than a dozen ’52 Mays cards for sale, but the pricing was unlike anything I had ever seen. Asking prices for VG copies were well north of $10,000 and the poor condition examples I was seeking were in the mid-four figure range. To someone who had been dubbed a “veteran collector” at a dealer table, this was a shock. I made my way to the common boxes and had myself an otherwise fine show.

Engaging in a mental debrief of the show on my three hour drive home, my primary issue became how to plan for the eventual acquisition of a card whose pricing had seemingly gone insane. A year and half later I had set aside enough funds for what I thought a ’52 Mays should sell for and returned to the Chantilly Card Show in Northern Virginia.

The good news was there were plenty of 70+ year old Willie Mays cards to choose from. The bad news was written all over the brightly colored stickers affixed to the plastic encasing the cards. Pricing of the (relatively) higher grade cards had pulled back a bit but was still elevated. Those cards wouldn’t be relevant to my collecting needs so I shrugged and moved on, picking up needed cards of Eddie Stanky and Johnny Berardino along the way.

Over the course of the next two hours I tracked down each ’52 Mays in the building. Low grade examples were all stickered at $4,000 and beyond. Making the optimistic assumption that such figures might only be a starting point for a conversation, I dove into my task. An informal survey of dealers carrying these cards quickly revealed a few things:

- A majority did not share my hypothesis about “conversation starters.”

- The most anyone would come off their asking price was 10%. Turns out that is what “I’ll work with you on price” means.

- About a third of those on the others side of the table asked for my contact information.

- Several said card show prices should be higher than those available elsewhere, as collectors can physically inspect the cards. Left unanswered were questions of how so many dealers who complained about their aging eyes being unable to focus properly would better inspect a card in person while the best online auction houses offer hi-res scans that magnify images 10x or more.

- All were willing to point out the relative attractiveness of a ’52 Mays over shiny modern cards with similar price tags.

- I wasn’t getting a Willie Mays card at this show.

With universal agreement on points 5 and 6 I drove home. Fortunately, I had a nearly untouched card budget and a backup plan waiting in the wings.

Aside from pricing and the emergence of Pokemon collectors, card shows are more or less as they were 35 years ago. There has been no improvement. The major auction houses, on the other hand, have become much better in this span. Conveniently for me, I had arrived in Chantilly with the knowledge that one of these auctions was underway with multiple examples of my target card. I returned home at 10PM, logged into to the auction, and promptly placed a bid for a fair condition Mays that was significantly below that asking price of the lowest grade beater seen in a dealer showcase. One week later a FedEx driver handed this to me:

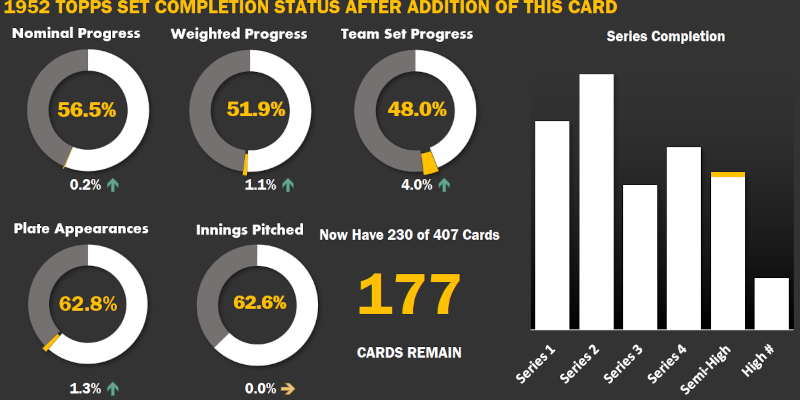

It is certainly one of the biggest highlights of my collection and one that took quite a while to eventually bring home. One of the issues making it so tough is its relative scarcity. While I doubt one can truly describe a card as “scarce” after seeing a dozen or more copies at a single card show, it is a component of the ’52 Topps Fifth Series. I have been crunching some numbers on the relative availability of the different series of this set and keep coming back to one conclusion: The Fifth Series is more plentiful than the high-numbered Sixth Series but not to the extent to which most of the hobby takes it. There is a lot more to explore in this area and I will be sure to write out my findings here at CardBoredom alongside the underlying data driving these conclusions. In the meantime, I’m going to spend some more time staring at this amazing card.

- A 524 card release from 1909-1912 was cataloged as a single set under the T-206 identifier in Jefferson Burdick’s The American Card Catalog. Although considered in popular collecting lore to be a single set, it is actually a series of smaller but nearly identical releases constituting multiple distinct sets. ’52 Topps was the king. ↩︎

- Fun fact: The ’73 Topps Home Run Leaders card makes an appearance on the bedroom wall of Benny Rodriguez in The Sandlot. It’s one of several cards produced at least a decade after the film’s 1962 setting. ↩︎