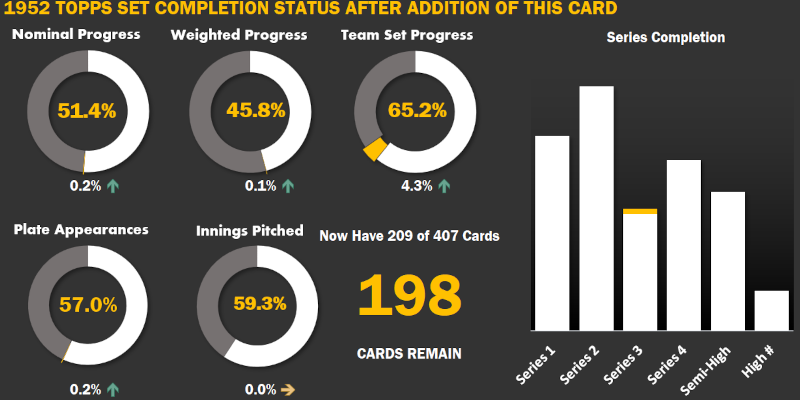

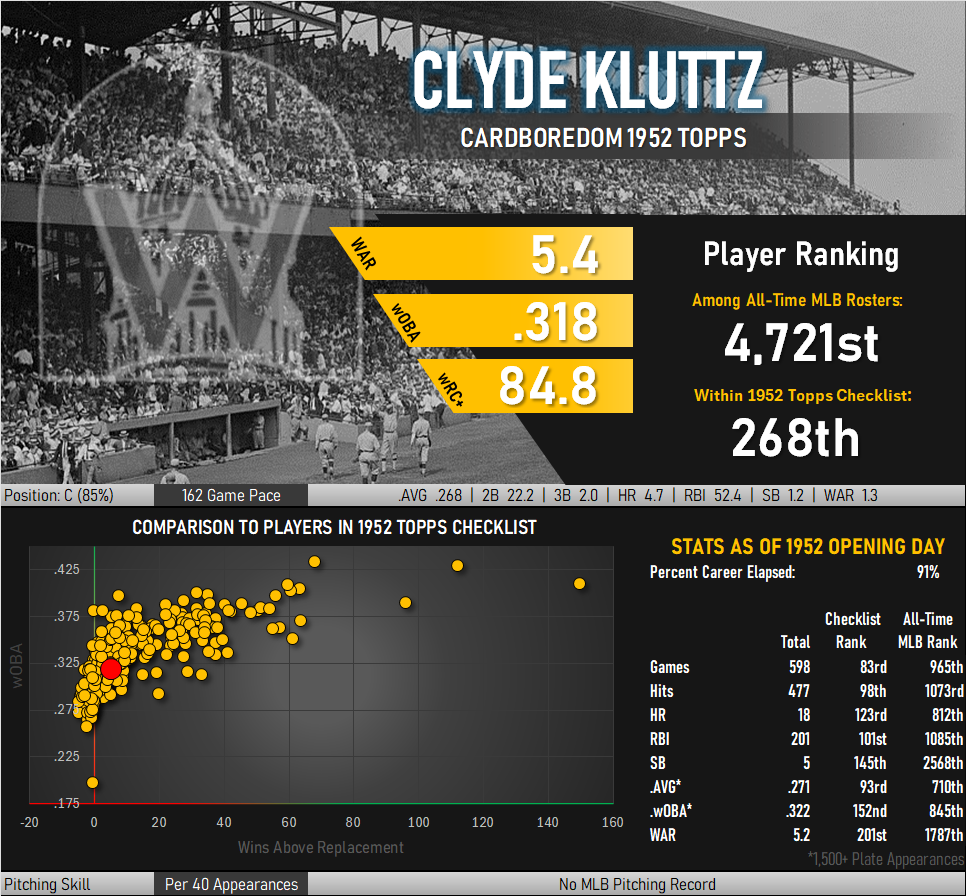

Earlier this week I took a look at the Mickey Harris card inhabiting my 1952 Topps set building project, a card that depicted the pitcher in his final season. The very next card I picked up likewise portrayed a 35-year-old player at the end of his career.

Clyde Kluttz was a career second string catcher who managed to play for a good deal of second string teams. The one time he played for a competitive team saw Kluttz and the St. Louis Cardinals beat Mickey Harris’ Red Sox for the 1946 World Series title. Cardinal pitcher Harry Brecheen, who famously won three games in the ’46 Series, specifically asked for the more familiar mitt of Del Rice to be behind the plate instead of his new teammate. Kluttz got a World Series ring but never saw action.

The most memorable part of his 52-game tenure with St. Louis is the manner in which the backup backstop arrived. Kluttz had played a half season in 1945 with the New York Giants and found himself in a multiplayer battle to backup Hall of Famer Ernie Lombardi. Seeing the writing on the wall after the arrival of Sal Yvars the following spring, Kluttz requested a trade and went as far as to threaten to abandon his contract in favor of the Mexican League if a new team was not found. Barely two weeks into the season, the Giants traveled to St. Louis to play against the Cardinals. The day before the single game series began, Kluttz was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for outfielder Vince DiMaggio. Philadelphia quickly flipped Kluttz to the Cardinals in a second trade, inking the deal in time for him to join the next afternoon’s game as an 8th-inning defensive replacement.

Brecheen’s decision to avoid Kluttz may have been forged in this moment. The game stood tied in a 1-1 starting pitchers’ duel as the scoreboard shifted into the ninth inning. Kluttz, who specialized in catching lefties like Brecheen, had performed well against the previous innings’ lineup. The Giants opened the inning with a single, moved the runner up on a sacrifice bunt, and brought him home on another single to gain the lead. A quick strikeout of the visting pitcher followed. Another single followed, scoring the runner. An unintentional walk followed, and was quickly succeeded by an error at second that loaded the bases. Another single was soon dispatched into right field, scoring two more runs and all but assuring Brecheen recorded a loss.

Kluttz, of course, wasn’t the cause of this misfortune. He was a decent but not spectacular backup who generally was not a liability to his team. His contract was sold the following spring to the Pittsburgh Pirates where he redeemed himself with a .302 batting average for the 1947 season. He kicked around for a few more years with the Pirates, Browns, and various minor league teams before emerging for a short stint with the Washington Senators in the year this baseball card was made.

The one stat that really stands out for Kluttz does not appear in the graphic above. He was very difficult to strike out. He whiffed in 5.7% of his plate appearances, on par with the selective batting eye of Don Mattingly.

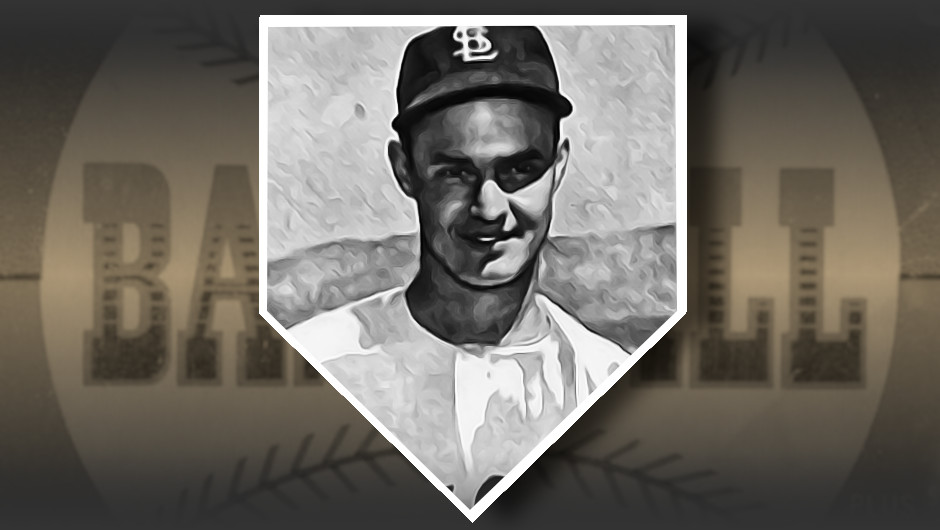

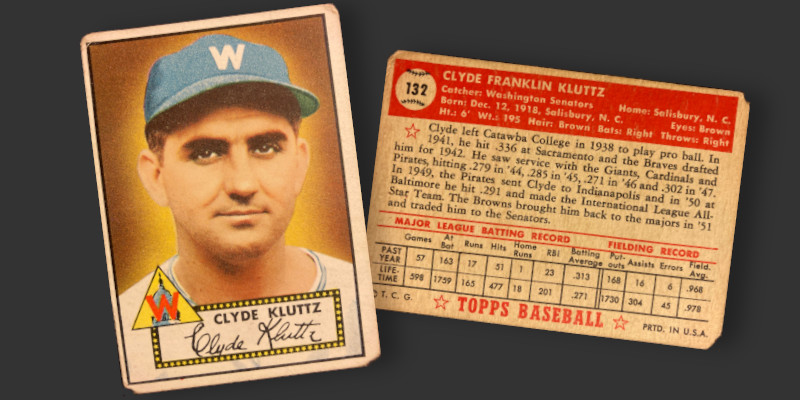

More About That ’52 Topps Card

Shown below is the Clyde Kluttz baseball card inhabiting my collection. That hat and jersey look more like altered St. Louis Browns’ paraphernalia than an actual Washington Senators uniform. Still, that 1951 stat line on the reverse looks pretty good with a .313 batting average across 57 games.

What doesn’t look as good are the corners. Each of them are well rounded, though observers may argue amongst themselves whether this card has four or six corners. This sort of damage is a regular feature of low grade cards from this set. It results from a corner being repeatedly bent back and forth until the underlying cardboard gives way and breaks off. The bottom corners have long ago escaped while the upper left bears a faint 45° surface break indicating it would eventually do the same if not properly stored.

Kluttz’s name has received the occasional bit of laughter from people looking at his cards. After all, shouldn’t a guy whose primary responsibility is catching a baseball be known for sure-handedness? Doesn’t “klutz” imply clumsiness? While I have seen the odd online comment or two about his name, I doubt kids opening packs in 1952 were making the same observation. “Klutz” did not enter widespread use in America until well into the 1960s. The word comes from a Yiddish term (klots) for a beam of wood or dumb lump. The States didn’t see much use of the term until the post-war years and even then it took a couple decades for it to start to seep into our lexicon.