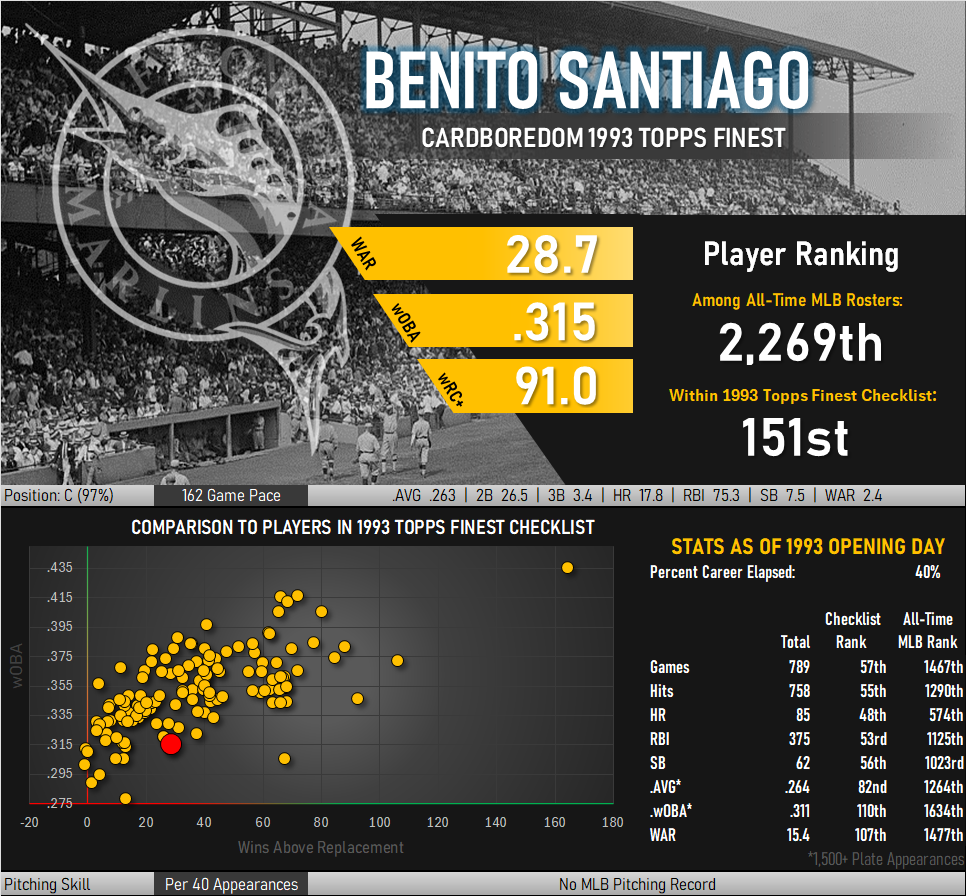

Benito Santiago kicked in the door when he entered the big leagues. In 1987 he was named Rookie of the Year, the most recent San Diego Padre to ever earn the accolade. That season he put together a 34-game hitting streak, a mark that has only been touched twice in the almost four decades since. He hit 18 home runs as a rookie and would go on to rank 15th all-time at his position.

Amazingly, his offense topped out in that rookie season and his batting skills ended up as a mild liability. What continued to make him a valuable addition to (numerous) lineups was superb defense. Like a very small number of amazing backstops, he could fire baseballs with accuracy while remaining in a crouch. Most catchers need to stand in order to use their legs to put extra speed on a ball. Santiago, on the other hand, could gain that extra second on baserunners and still hit his target. This was an arm that had drawn attention throughout his life, and it has been noted that he once authored nine no-hitters as a pitcher before becoming a professional.

Things were looking up in 1987, but a series of missteps (he publicly said the Padres’ rotation “stunk”), regression from rookie success, and rising labor unrest in the sport caused problems. Santiago grew increasingly frustrated with San Diego’s front office, and eventually requested a trade in 1991. The team turned down his request, so he set about the task of publicizing the team’s deal-making acumen. The space above his locker door became the home of a growing baseball card collection. Each time a player moved on from San Diego, his card would be added to Santiago’s “Former-Padre” card wall. Baseball players (and members of the media) who saw the growing card collection would stop by to ask about the cards and Santiago would explain how he thought the players depicted should have never been traded or otherwise allowed to leave for other teams.

I have never found a picture of this card collection or identified exactly which cards comprised the collection. Had he been collecting cards all along in his professional career? Where his ex-Padres cards all from the same set? Did he buy singles or open packs himself until he found who he was looking for? Where the cards specifically chosen to have meaningful pictures or were they just whatever was available?

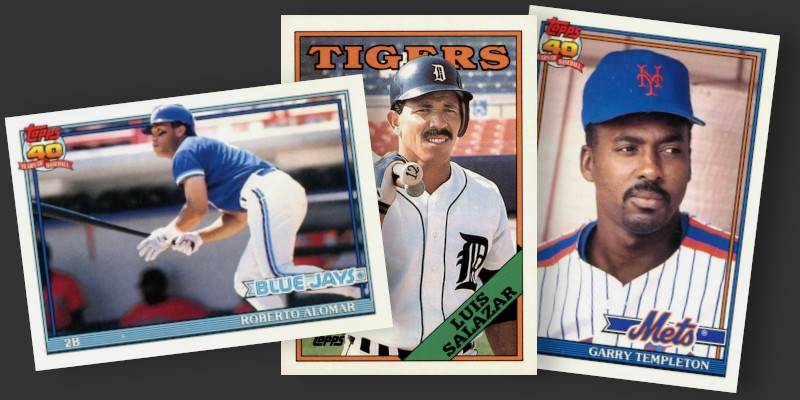

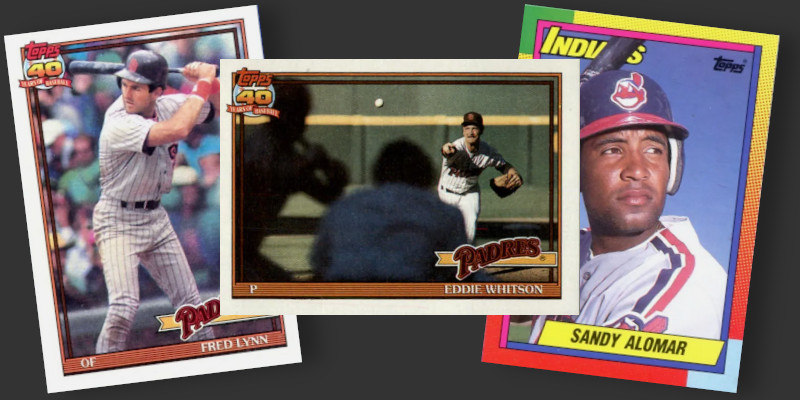

While I do not have answers to these questions, I do know exactly which players comprised this group. The cards became a subject of conversation with players and reporters alike when San Diego hosted the 1992 All-Star Game. At least one reporter jotted down the list of players when speaking with Santiago and Craig Biggio, who had wondered over to ask about the collection. Below appears my impression at what this stack of cardboard could have looked like, assuming it was put together with cards produced using post-season traded cards or regular issues from the year following a departure.

I get what Santiago was saying with the first 9 cards. There are a few players that left with athletes received in return arriving with less name recognition. Many of the departed players left as free agents, presumably because San Diego kept contract offers on the low side. Santiago was himself embroiled in compensation disputes, twice going to arbitration with the team over upcoming contracts. In his mind, these players would not have moved on to other clubhouses if the Padres had simply opened their wallets. He undoubtedly would have seen himself as a beneficiary of such a change.

Several cards are a bit more of a head scratcher. Fred Lynn retired as a member of the Padres at the end of 1990, but still earned a spot in Santiago’s “they should still be in San Diego” collection. Lynn was 38 years old and had just hit .240. He was obviously on the downslope of his career and likely was not about to return to his usual All-Star level performance. My guess is Santiago saw this as the Padres again not wanting to open their checkbook rather than the end of an impressive career.

Ed Whitson retired at the end of the 1991 season. Sure, the Padres could have offered him a final contract, but the truth was that his elbow was seriously injured and he would be unable to pitch again.

Sandy Alomar represents another interesting card in Santiago’s collection. Alomar played the same position as Santiago and was in direct competition for his job. He was capable of taking it too, as he would win the American League Rookie of the Year immediately after being traded to the Cleveland Indians. The Padres already had Santiago behind the plate and received slugger Joe Carter in return. I don’t see how Santiago could fault this move.

Presumably Santiago was okay with the departures of players not included in these cards. There are no cards of former Padres Carlos Baerga or John Kruk. It would also be implied that he was unhappy with the players joining the Padres in these transactions, a group that includes the likes of Fred McGriff and Tony Fernandez. Santiago even went as far as to use his cards to say trading Sandy Alomar for Joe Carter was a bad idea, then complained that sending Carter to Toronto for Fred McGriff was a mistake.

Santiago finally got his wish to be free from the Padres with the expiration of his contract at the conclusion of the 1992 season. A free agent as of the end of October, he was not part of any MLB roster when the Expansion Draft took place that would stock the rosters of the newly created Colorado Rockies and Florida Marlins. Florida selected three catchers from other teams and then, after trading one back to the Athletics after one day, reached out to nab Santiago from free agency.

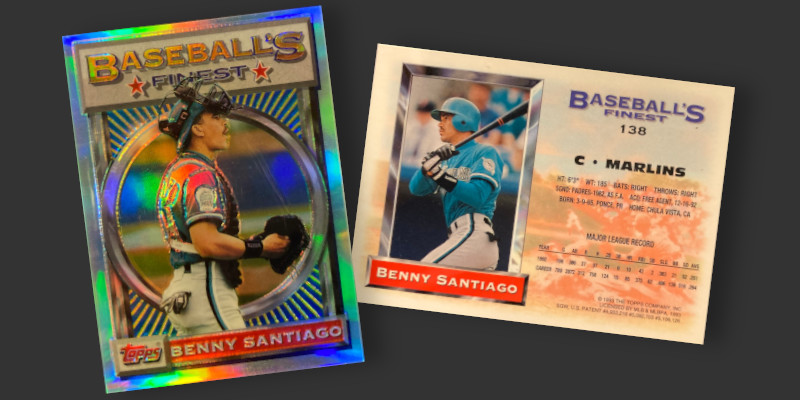

The Marlins had three catchers on the squad when their debut season rolled around and it was Santiago who ended up with the starting job. He is the lone Marlins backstop in the 1993 Finest set and the resulting card is a glorious celebration of all things teal. The refractor version exhibits one of the better uses of color in the set. Santiago’s dark jersey displays a range of colors while a plethora of catching gear creates numerous embossed edges to catch passing light.

He made the most of his three-year Florida tenure, hitting the first home run in team history. He left when he became eligible for free agency, an outcome that would repeat nine more times with eight teams in the future.

Fun Fact: A decade prior to appearing in the 1993 Finest set, Santiago had played minor league ball for the independent Miami Marlins.