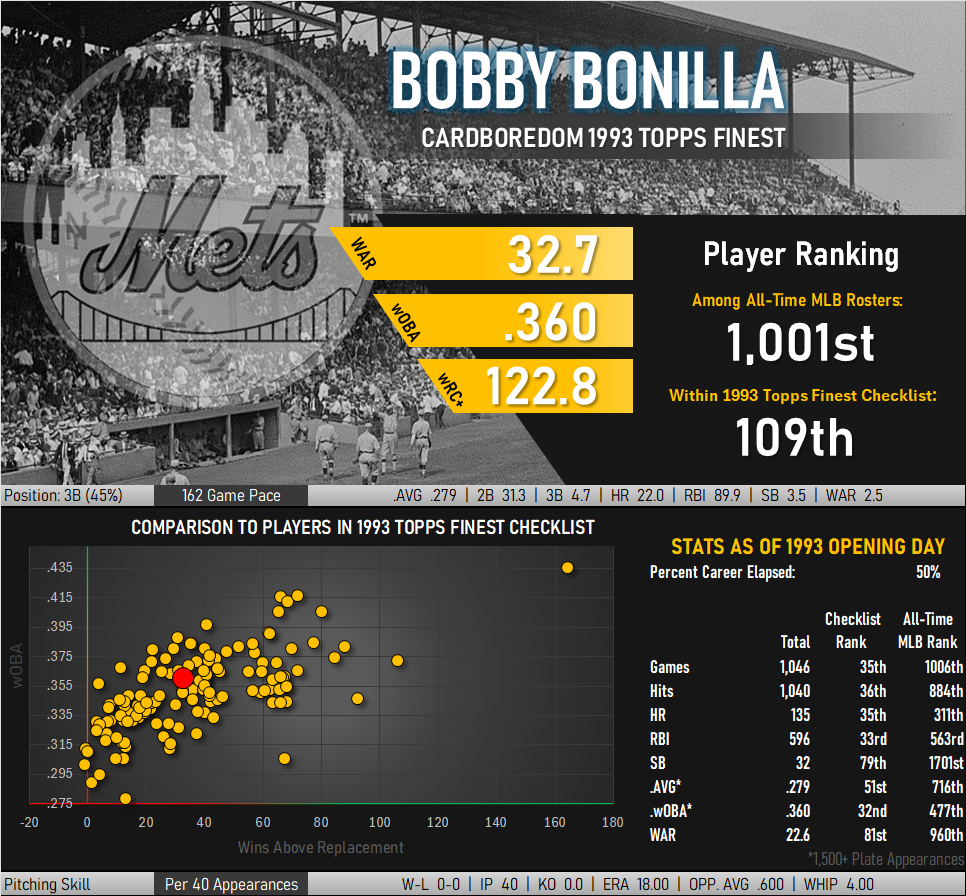

Bobby Bonilla was a fun player to watch in the batter’s box (watching defense was an entirely different experience). He put together a solid offensive record, banging out over 2,000 career hits and nearly 300 homeruns. Perhaps his greatest legacy is a trail of transactions that boosted teams into championship contention.

The Pittsburgh Pirates traded for him in late 1986, pairing him in the lineup with Barry Bonds and leaving National League pitchers no choice to but to engage with a one of the most fearsome offensive duos of the day. The Pirates challenged for the NL championship in consecutive years, leading to multiple teams bidding for the services of one of the team’s best hitters. He spent several disappointing seasons with the New York Mets before being traded to the lowly Baltimore Orioles. The next year Baltimore made it to the American League Championship with Bonilla slugging 28 HRs and 116 RBIs. He went to the Florida Marlins in 1997 where the team promptly captured it all in the World Series. He came back to the Mets in 1999, a year in which the team played in the NLCS. In short, his presence was connected with a decade of deep postseason runs.

The Mets, it seemed, were his kryptonite and it is in one of their uniforms he appears in the 1993 Finest set. He wasn’t terrible in New York, he just wasn’t the caliber player he had been in Pittsburgh. Much of that is likely related to his prior role of protecting Bonds in the Pirate lineup. In New York he had only the fading bat of Howard Johnson to back him up, resulting in a year-long period in which he adjusted to pitchers coming at him head-on. He figured it out, but not before getting on the bad side of NY fans and the Mets front office making a decision that would be forever connected with his story.

The Contract

The Mets watched their former slugger take Baltimore to the ALCS and win a World Series ring with the Florida Marlins. The Marlins, for their part, had paid for Bonilla’s services by signing him to a 4-year deal with an annual salary of nearly $6 million. After winning the series in 1997 the team then underwent an owner-induced fire sale as the team was prepared to be sold. Bonilla was traded (along with stars like Gary Sheffield and CJ Johnson) to the Los Angeles Dodgers. The Dodgers, in need of pitching, traded Bonilla to the Mets. The result was the reunification of Bonilla with the Mets for the remaining two years of his contract.

At this point Bonilla was starting the season at 36 years old in a league that did not allow designated hitters. While the team did go to the championship series, Bonilla contributed only 4 homeruns and a .160 batting average over a full season of play. The team was so close to getting to the World Series and it seemed just one more free agent addition could get them there. Bonilla wasn’t likely to drastically improved at age 37 and his $6 million salary (set by the Marlins) was owed for one more season.

This is when phones started ringing. It was proposed that the Mets buy out Bonilla’s contract, giving him his earnings and freeing up a roster space for another player. Bonilla would be free to seek a team that would provide him the regular playing team that New York would not be offering in the upcoming season. Bonilla’s agent, Dennis Gilbert, is generally credited with suggesting a way of paying Bonilla while still allowing the Mets to use the funds to attack the free agent market.

The parties drew up an amendment to the contract that called for Bonilla to be immediately freed from the team (he signed with the Atlanta Braves for 2000 and would get to the playoffs). He agreed to defer receipt of his remaining salary into the future, allowing the Mets to use the cash to pursue a high-priced replacement. In exchange for this, the Mets promised to pay his salary (with interest) in 25 equal installments that would begin a dozen years later.

This worked out…really well? The Mets acquired Mike Hampton, a much-needed starting pitcher coming off a 22-4, 2.90 ERA season. He helped carry the team to the NLCS where he promptly earned the series’ MVP award. Hampton left the team the following season, but not before the Mets were awarded a compensatory draft pick for their departing player. His replacement was David Wright, effectively making Bobby Bonilla the catalyst for one of the Mets’ best memories of the early 2000s.

The transaction did not gain traction in the public consciousness until payments began in 2011. At that point the Mets were in dire financial straits as much of the Wilpon family’s liquid investments was tied up in smoldering ruins of Bernie Madoff’s ponzi scheme. With the family finances unable to backstop pursuit of key players, the team fell from contention. Irate fans, who rightfully should focus on ownership and the actions of a thief, seized upon the $1.2 million annual payments to Bonilla that were just beginning that year.

Today, nearly a dozen years after payments began and halfway through the 25-year payout period, the contract has become the stuff of baseball lore. It was certainly a good deal for all involved and I am glad to see some semblance of acceptance begin to creep back into the story of how it came about. Such arrangements are becoming commonplace, with and Manny Ramirez, Bret Saberhagen, Bruce Sutter, and Ken Griffey, Jr. all receiving payments under similar arrangements.

A mention of Bonilla’s contract draws a smirk from Mets fans while little reaction is elicited when speaking of Griffey’s annual payouts. Here’s an interesting fact to bring up the next time someone mentions Bobby Bonilla Day (the date annual payments are made): Bonilla generated 9.1 WAR in less than 5 seasons for the Mets while Griffey took an extra 4 years to create 10.1 WAR. Only once in that decade long span did Griffey outpace Bonilla in annual WAR production.

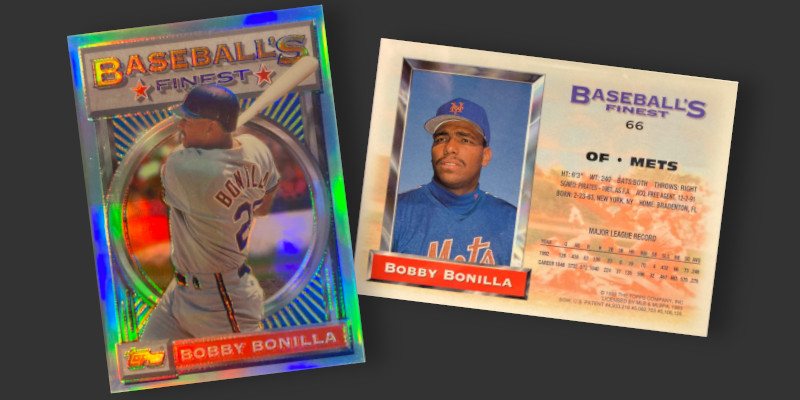

My Second Favorite Bonilla Card

The history of Bonilla’s contract and the Mets has combined to make his ’93 Finest my favorite card of his career. Sure, he won a World Series in Florida and repeatedly challenged for league championships in Pittsburgh, but it is his hometown of New York that will forever be linked with his story.

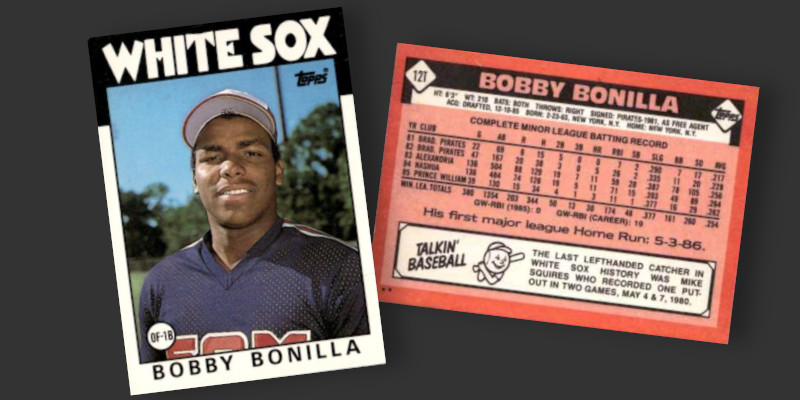

A close runner up is a card that takes him away from New York. Bonilla appears as card #12T in the 1986 Topps Traded set, a collection of cards so good I believe it to be the greatest set of the 1980s. He appeared in each of the major manufacturer’s year end sets but it is his Topps issue that so prominently identifies him as a member of the Chicago White Sox, a team for which he briefly played in an unlikely path to the majors.

Bonilla grew up in the southernmost section of the Bronx, putting his school years in the middle of one of New York’s more violent neighborhoods. Bonilla spent his time on the diamond and made his name available for the MLB draft in 1981. There were no takers. He still wanted to play and made time to take part in overseas baseball camps where a Pittsburgh Pirates scout eventually took notice. He spent the next 3+ years playing low-level minor league ball. Bonilla had a shot to jump to a higher level in 1985 but suffered a leg injury during Spring Training, relegating him to a shortened season in Class-A ball.

Baseball has rules in place to prevent teams from stockpiling talented players in the minor leagues. They either need to play at the top level or eventually be made available to other teams. The catch accompanying this ability to nab prospective players is that the acquiring team must keep the player in question on its active roster for the entire season. The Chicago White Sox grabbed Bonilla and promptly put him into 75 games.

Pittsburgh had since replaced its general manager with the scout that had discovered Bonilla. He promptly engineered a trade and slotted him into 63 games for the Bucs over the remainder of the season. The next year he was penciled into the lineup behind a young Barry Bonds and the pair promptly became an offensive force, eventually finishing 1/2 in 1990 MVP voting.

This is a great card because it captures Bonilla at a point where he could finally prove himself against a backdrop of zero expectations. He grew up in a gritty area, was completely ignored by the draft, was left to languish in the most obscure minor league rosters, and then showed he had the ability to play with the best of the game in his first opportunity. There’s not many other cards that embody the “just give me a chance” ethos than this one.

The Bonilla Refractor

This card was acquired in my first experience buying cards on COMC. Today Bonilla cards are usually priced as commons, making landing this one for my set-building project an easy pickup. This wasn’t always the case and collectors of the early ’90s may have needed to decide between buying one of these or a Super Nintendo.