“Ron Artest has a look in his eye that is very scary right now.”

That’s the quote from the play by play that I remember from perhaps the biggest fight at an NBA basketball game. After fouling Detroit center Ben Wallace and then receiving a retaliatory shove in the face, Artest was hit by a drink thrown by a fan. He bolted into the stands and mistakenly grabbed another spectator, an action that touched off an already boiling over situation on the court. Within seconds multiple fights were breaking out across the arena, prompting the premature calling of the game and the dispatch of a large police presence to clear the Detroit home court.

This wasn’t nearly the first time a professional athlete in the Motor City took to the stands to engage a fan with his fists. Incessant heckling from a spectator enraged Ty Cobb to the point where he stormed the grandstands in 1912. Cobb began beating the strong-voiced man, making full use of his fists as well as his frequently sharpened metal cleats. The fan, it should be noted, had lost most of his hands in a prior accident and could not mount much of a defense against the Tigers’ celebrated sociopath. Cobb’s teammates formed a cordon blocking others from assisting Cobb’s opponent, maintaining their defense until the arrival of a uniformed officer. Cobb was subsequently suspended indefinitely and his teammates went on strike in protest. To prevent a forfeit in the next contest, Detroit fielded a team of local college and sandlot players for what became one of the most lopsided games in baseball history.

Three decades later another hot-headed Tigers player took matters into his own hands amid the hometown stands. Having already played three seasons in the majors, Dizzy Trout had gained a reputation as a superb pitcher with an equally volatile temper. He typically pitched lights out baseball, but would lose command of his pitches whenever he became upset. On September 11, 1942 Trout had been slowly giving up runs to the Philadelphia Athletics, ending the sixth inning with the score standing at 4-1. Unhappy with the game’s progress, a local fan began riding Trout. He responded by running to the sidelines, climbing into the seats, and dragging the man onto the field for a beating. Trout was removed from the game and his teammates made no move to strike or otherwise protest the decision.

Dizzy Resembles Dizzy

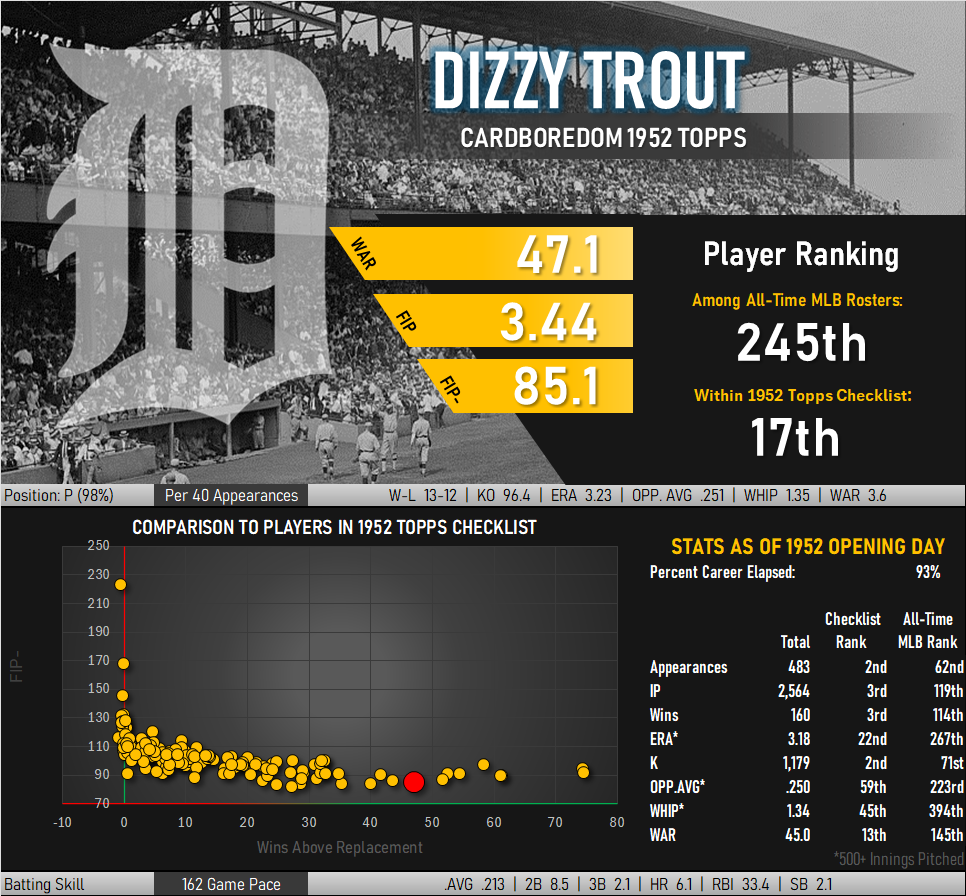

Dizzy Trout had a temper that he never really learned to control, but he also had an arm with terrific aim. Trout rode that arm to close to 200 victories and almost 50 wins above replacement. Every season was marked with above average fielding independent pitching. Dizzy told anyone who would listen that he modeled his performance on Dizzy Dean, the star of the St. Louis Cardinals’ championship teams of the 1930s. He liked Dean’s pitching and talkative manner so much that he adopted his idol’s nickname.

Trout was very well known during his playing days and was considered a star at the time. During one four year stretch he tallied 82 wins. In 1944 he logged 27 wins with 7 shutouts and a 2.12 ERA. His name has lost some of its notoriety in the subsequent decades as his pitching happened to take place in the shadow of the 1940s best hurler, Hal Newhouser. Just as few people can name the second best pitcher behind Nolan Ryan on the Angels’ and Astros’ staff, the number who truly appreciate Trout’s skill remains limited.

Casting About for a Trout Upgrade

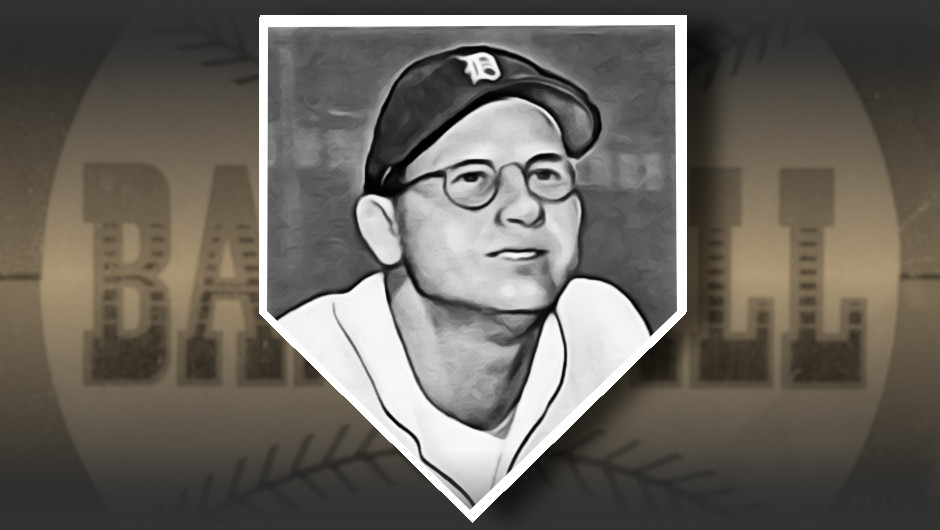

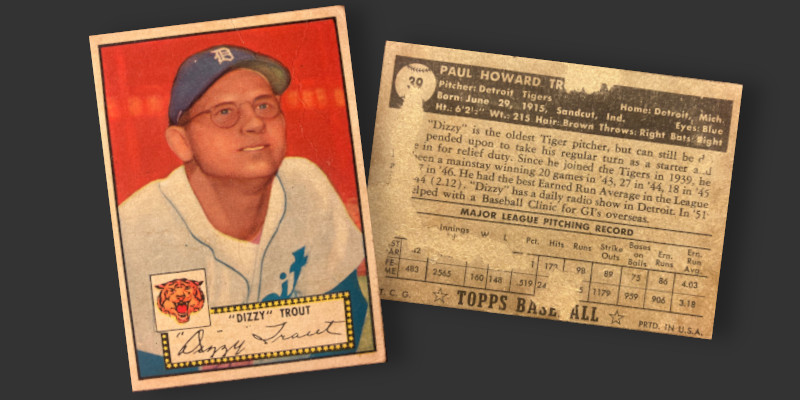

I picked up a couple different cards when adding Dizzy Trout to my ’52 Topps collection. The one shown below is the first and was acquired when several commons from the set became available from an eBay seller offering free shipping for each additional purchase. It looks great on the front but is missing a good deal of real estate from the back.

A second copy joined a couple months later as an upgrade. A similar free shipping offer lured me deep into a seller’s online inventory. Among the search results was another ’52 Trout for just over a buck and seemingly suffering only from some centering issues and corners exhibiting GD-condition wear. When the card arrived I found it also had a creasing making its way across the entire card. The crease did not break the surface ink but is highly visible when held under a light. Technically the second card is in better condition than the original, but the one with the torn back looks better. I’m keeping the first one.

The red background used on the card appears multiple times in the set. Until I saw this card I had assumed the red backdrop with seemingly random pale squares was nothing more than an abstract design. This card sets Trout at a bit more of a distance that others, revealing the backdrop to be the space between the upper and lower decks of a stadium. This isn’t a random design, but rather a tinting of the existing background with a deep red hue.

The visible portion of the biographical text on the back mentions that Trout is the oldest pitcher on the Detroit staff. At age 36 this would also make him the elder statesman of Detroit’s 2023 pitchers. 1952 was Trout’s last regular season, one that saw him traded mid-season to the Boston Red Sox. He retired at the end of the year and took up the post baseball profession of Dizzy Dean, calling publicly broadcast ballgames.

Like many retirees, Trout soon found himself considering a return to his previous line of work. The Baltimore Orioles signed him at age 42, nearly five years after his last pitching appearance. Trout got into two games for Baltimore in 1957 but managed to only record a single out before hanging up his glove for good.