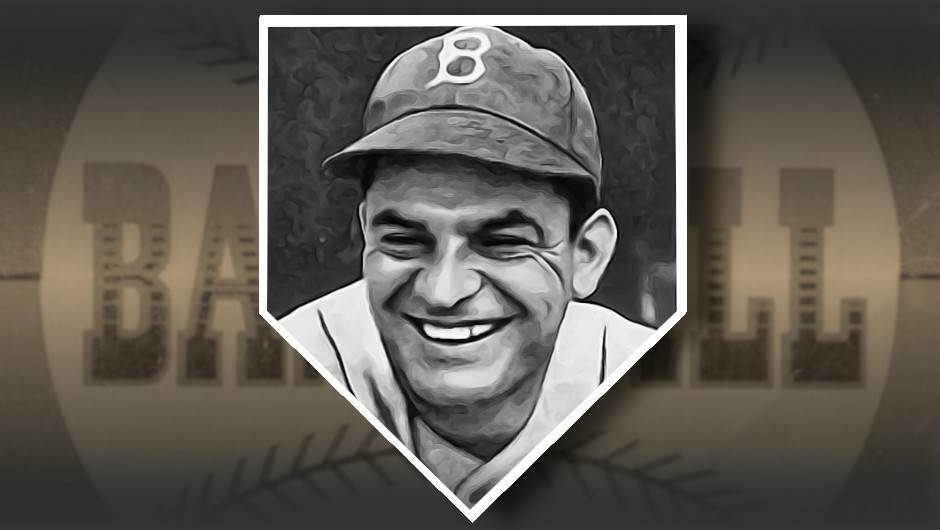

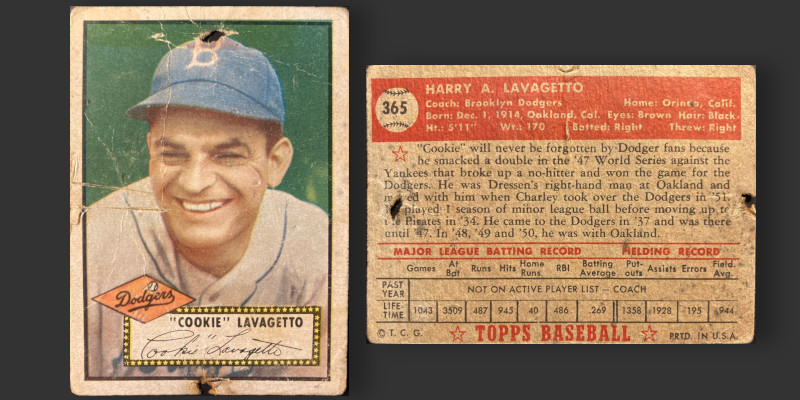

The 1952 Topps set featured Cookie Lavagetto as a coach in its limited high-number series. His inclusion made sense given the preponderance of New York-area coaches and managers filling out the final series checklist. Even though he didn’t have the name recognition of fellow non-active players Leo Durocher and Bill Dickey, Lavagetto likely would have found welcoming collectors at the time as he had a tendency to attract fan clubs.

Home games at Ebbets Field was the center of one of these clubs. During the early 1940s a local bar owner set up a boozy cheering section along the third base line, complete with banners supporting Lavagetto. Multiple cabs were hired to ferry the unofficial club to games along with masses of balloons that would be released throughout the game.

Lavagetto served as a coach after his playing days ended, creating quite a reputation among a slew of future major league managers. Casey Stengel and Chuck Dressen both took note, each asking him to follow their paths with big league clubs. Lavagetto obliged, working closely with both and eventually replacing Dressen as manager of the Washington Senators and becoming the first manager of the Minnesota Twins.

Fan mail arrives for most players, though it can be a bit surprising to see large volumes directed at a somewhat average one. Sports Illustrated reported in 1960 that the entire town of Windham, MT sent him a telegram of encouragement. The article even goes on to describe inmates in a Maryland prison reaching out to him.

The best part of all this? Lavagetto’s real name isn’t “Cookie.” The nickname is derived from his one-man fan club that took the form of Cookie Devincenzi, owner of the Pacific Coast League Oakland Oaks. His backing of Lavagetto was so forceful that the player was known as “Cookie’s boy” and then “Cookie.” How often does a player get named after his own fan club?

Appearing as a coach in the 1952 Topps set, Lavagetto was a throwback to depression-era baseball. Cards from the era showed remarkable ingenuity as manufacturers competed for sales. Shown above is his card from the 1934 Batter-Up set, an issue that invited collectors to fold their cards into free standing models of their favorite players.