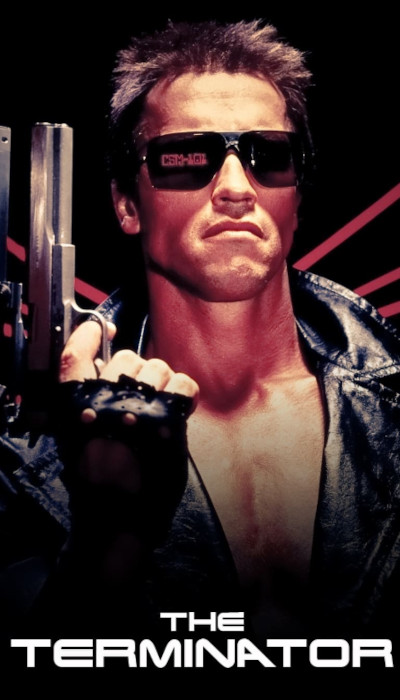

The sci-fi thriller “The Terminator” hit theaters in October 1984, forever ingraining Arnold Schwarzenegger in audiences’ minds as the face of the titular time traveling robot assassin. The plot revolves around humanity building SkyNet, an AI-based weapons system, only to have it become self aware and turn against its creators. Human resistance eventually makes headway against the rogue system, led by a young man named John Connor. Faced with Connor’s creativity and leadership skills, the robots send one of their relentless assassins back in time to kill his mother before he is ever born. While Schwarzenegger failed to terminate his quarry, he did succeed in getting everyone to say “I’ll be back” in monotone by the end of the year.

The film would eventually spawn at least five sequels and accomplish that rare feat in which a sequel is just as good as the work that started the series. The second installment focuses on a pair of dueling cyborgs in a life and death race to track down the now ten-year old John Connor, but that would not arrive in theaters until 1991. Until then, things looked pretty good for the younger kids growing up in the 1980s. The Terminator had been defeated and Judgement Day forestalled. Super Mario and other computer generated characters were our friends.

1984 also presented us with a handful of young pitchers who came into their own that year. Fans saw NL Rookie of the Year Dwight Gooden and AL runner up Mark Langston tear up their respective leagues, looking more like established veterans rather than faces that had never thrown a major league pitch before that season.

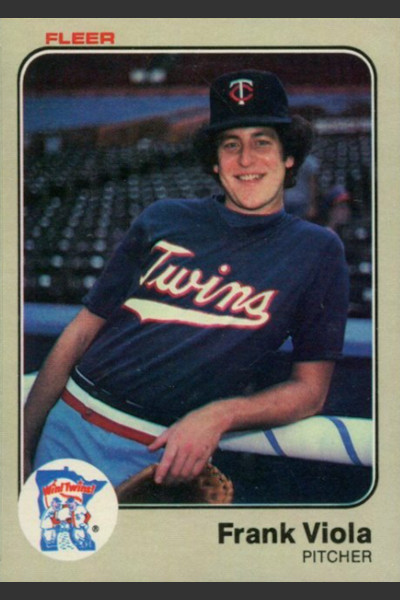

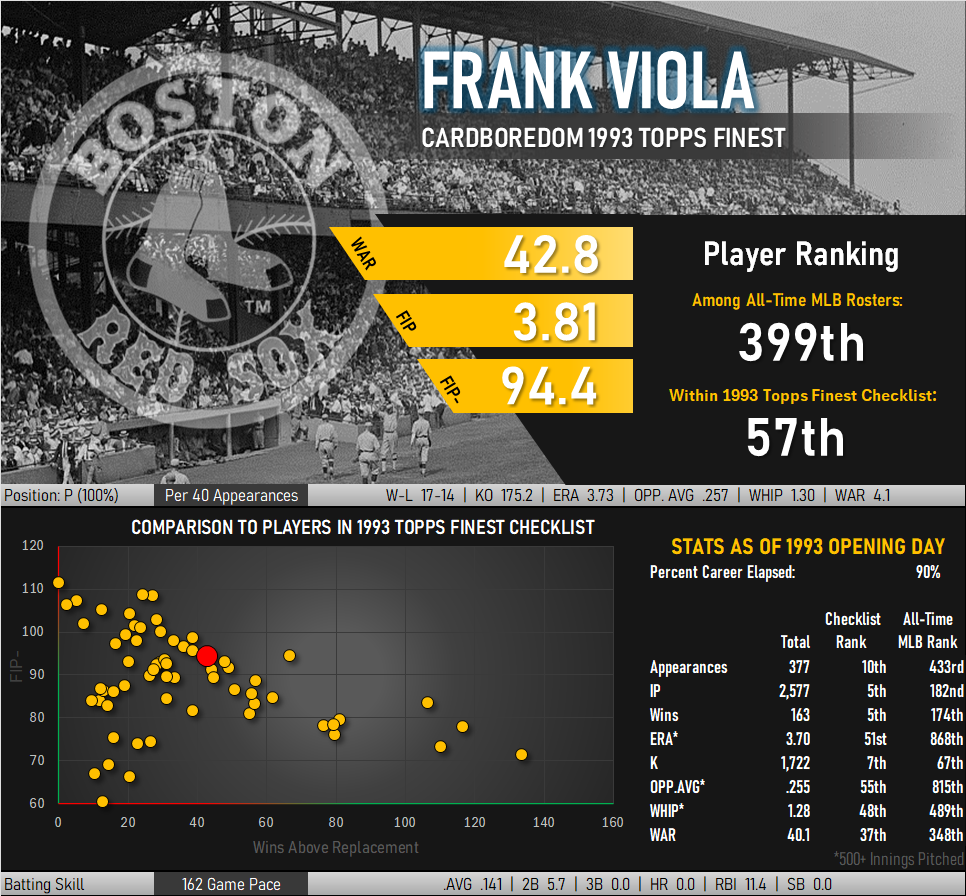

The competition must have helped, as Twins hurler Frank Viola transformed from a negative-WAR pitcher with an ERA well above 5.00 into a frontline starter that would generate nearly +5 WAR annually for the next decade. Not bad for a guy who a year earlier could have been mistaken for one of the bike-riding teenagers from the film E.T.

Those are solid numbers posted by the pitcher known as “Sweet Music.” His lifetime WAR and FIP metrics put him roughly on par with Bartolo Colon (actually a bit better) when viewed through the lens of more recent players. So why should we bother looking to a future time to evaluate Viola’s performance? Because regardless of how young he looked his destiny would be to fight bots in 2019.

Before he could get to that point, he had to get past The Terminator in the 1980s and 1990s. Marching almost in lockstep with Viola’s career was that of relief pitcher Tom “The Terminator” Henke. Both made their MLB debut in 1982, switched teams with regularity, and even briefly moved to the National League at the tail end of their careers. They came into direct competition on exactly 9 occasions, producing the following stat lines:

| Pitcher | IP | Record | Saves | SO | BB | WHIP | ERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viola | 66⅓ | 3-4 | 0 | 48 | 17 | 1.27 | 3.26 |

| Henke | 13 | 2-0 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 0.92 | 2.08 |

Viola Leads the Resistance

More than two decades after hanging up his glove, the Terminator’s opponent found himself unexpectedly thrust into an existential battle for the future direction of baseball. At this stage Viola was employed as a pitching coach for the Atlantic League’s High Point Rockers, putting him at ground zero for the arrival of electronic umpiring.

TrackMan has been marketing its automated ball and strike (ABS) system to organized baseball since 2011 and found its first large scale professional deployment with the Atlantic League eight years later. The ABS system uses a doppler radar array to acquire and track a baseball from the moment it is thrown to the point where it passes home plate. More than two dozen discrete data sets are produced for each pitch, allowing for all kinds of analysis. The most interesting of these is the exact location of the pitch in relation to an automatically inferred strike zone. The relative positioning of the pitch against this zone is relayed instantly to a human umpire who relays the result to the waiting audience via traditional verbal and hand signals.

The system faced no minor amount of pushback, led by nonother than Frank Viola. In the very same week in which ABS made its Atlantic League debut, Viola walked out to home plate to argue with the umpire against a called base on balls. Not taking the raw data as proof that his pitcher couldn’t place his pitch, Viola was quickly ejected from the game (smiling mischievously all the way back to the clubhouse). Human/computer conflict had come to pass for the first time on a professional ballfield and this time it was the retired veteran lefty who left the words “I’ll be back” hanging on the air.

Showing Viola the output of the radar system may have made him more resolved than ever to argue the call. He wasn’t pushing back against an incorrect call on the placement of the pitches, but rather against the rulings being too accurate. After the game, he explained to reporters that he thought TrackMan was too consistent. Human umpires have traditionally exercised some flexibility in interpreting the strike zone to help dictate the pace of play. As a control pitcher, he had benefitted from umpires expanding the strike zone for those who could consistently locate their pitches. A truly accurate ABS system would erase that “feature” from the game.

Suffice it to say I am firmly on the opposite side of Viola’s argument. I am as big a proponent of expanding the digitalization of the game as one can imagine. There’s a lot to break down in these thoughts and for the sake of keeping my posting schedule on track I will save them for an upcoming discussion of Greg Maddux and pitch placement later this year.

Resurrecting a Trend From the Deadball Era

Increasing automation in umpiring duties interjects the potential for an extra layer of entertainment value to the game. Imagine if we took these trends a bit further, expanding the rules-based decision making to cover the other parts of an ump’s to-do list. Theoretically his role could be transformed into that of an actor playing the role of umpire with a script generated by the raw data of the action on the field. The quality that makes a good umpire today (invisibility) would be replaced by the qualities that make an umpire fun to watch.

In this scenario actual actors and celebrities could don the familiar costume of sport coat, pads, and face mask to enhance an exciting atmosphere at the ballpark. Instead of a celebrity merely throwing out a ceremonial first pitch, they could call the result of every ball speeding towards the catcher’s mitt.

Celebrity umpiring isn’t entirely unprecedented in baseball history. Wild Bill Hickok, the famous Old West gunfighter, once umpired an 1866 Kansas City Antelopes contest while armed with a pair of six-shooters. Boxing champion John L. Sullivan, who occasionally played semipro baseball, served as an umpire and master of ceremonies at several games during his athletic prime. Just imagine a bench clearing brawl in which the heavyweight champ dives in to dish out some swings of his own!

Reviving this long-lost tradition could inject a fresh dose of fun into the sport. Can you envision Snoop Dogg calling “shizzles” and “bizzles” from behind the plate or Taylor Swift telling an upset batter to “shake it off?”

I don’t think Frank Viola wants to find out.