Gil Hodges’ early death came as a shock in 1972. The event is still something remembered by those who formed memories in that era. He had been an extremely popular figure in the nation’s largest sports market and was idealized by fans across team allegiances. To put into context the impact his passing, think about Derek Jeter. Today he is just two days away from his 48th birthday, the same as Hodges when he was felled by a heart attack while golfing with friends. Baseball itself would almost die from grief if Jeter didn’t wake up tomorrow. That‘s how fans felt reading the newspaper days before the 1972 season got underway.

So why did Gil have such a following? For starters, he served in the Marine Corps in WW2 and was decorated for valor in the Battle of Okinawa. He joined the Brooklyn Dodgers and quickly became one of the primary offensive forces of the team for the next decade. He finished the 1950s with the decade’s second highest HR and RBI totals while racking up 7 consecutive All-Star appearances. He drove in every single one of the Dodgers’ runs in Game 7 of the 1955 World Series, the only year in team history they would win the championship. Hodges retired with the National League record for career grand slams and his lifetime HR total ranked 11th all time. His defense was subperb and he is considered one of the better first basemen of all time despite not playing the position until after he made the majors. After his playing days concluded he managed the woeful Washington Senators, improving their record each year. He returned to New York and led the terrible Mets to their improbable 1969 championship, seemingly inventing the modern 5 man pitching rotation in the process. Countless stories exist of Hodges filling in for players that could not make community engagements and refusing to take payment for his appearances. He did all of this with an incredibly calm, quiet demeanor.

In short, Hodges had the respect of everyone who came across him. He didn’t demand it, the respect was just something that others felt he deserved. There are no reports of him being booed by the same crowd that had no problem throwing marbles at the likes of Duke Snider. Roger Kahn’s The Boys of Summer recounts one instance where Washington ballplayers had broken team curfew. Hodges, as manager, told the team he knew four players broke the rules and would be fined $100. The penalty would be assessed on the honor system. That night seven players slipped $100 bills into a box provided for the purpose.

Gil Hodges was elected posthumously to the Hall of Fame in December. Clearly a member of the Hall of Very Good, his stats trailed several of his contemporaries that had not lost time to military service. His early death cut short what was becoming an impressive managerial career and the Golden Era Veterans Committee members that voted him in looked at the combined effect of these contributions to the sport.

One of Gil’s More Interesting Cards

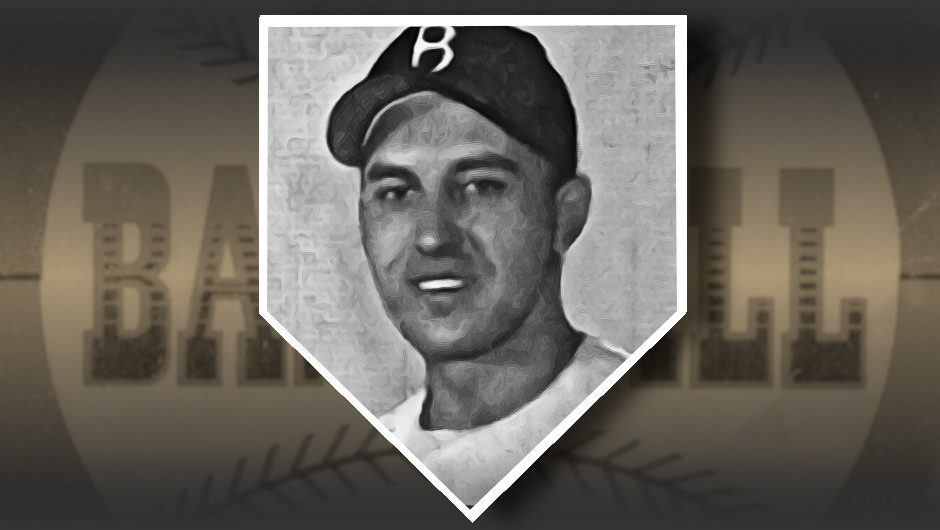

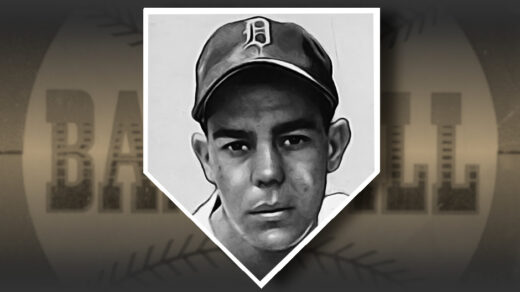

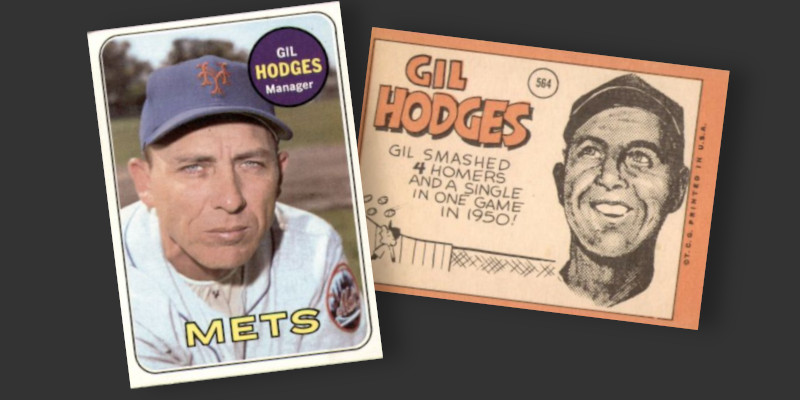

Hodges’ playing ability was well documented and almost any card from his days as an active player would be greatly appreciated. His 1952 Topps card could easily be the cornerstone of a collection focused on the man. However, if only given a single card to represent his impact I would select his 1969 Topps issue. This card features him as a serious-faced manager rather than a smiling player. The set’s design makes prominent use of the Mets team name, a feature that makes the card what it is as the team became one of the unlikeliest champions in history under Hodges’ tutelage.

The back of 1969 Topps manager cards are also great because they include an ink sketch of the card’s subject. I learned to draw faces from these cards and still have a fond spot for them.

Ted Williams Plays the Villian

Whether or not the Hall of Fame should be constructed to include players like Hodges is an evergreen argument. Hodges’ experience with HOF voting, however, did firmly shed light on the hypocrisy that is Ted Williams. In 1993 Williams chaired the Golden Era Veterans Committee, which took up Hodges’ case for enshrinement after he fell off the writers’ ballot. Hodges routinely came close on the BBWA vote, but fell short given the requirement for voters to only consider time as a player. The Veterans Committee could add his effect on the game through other means, most notably his contribution as a manager.

Hodges received 12 of 16 votes, giving him the necessary 75% approval rate for inclusion. Williams halted the proceedings and nullified the “yes” vote from committee member Roy Campanella. He stated that the vote should not count as Campanella had not cast it in person as the rules state. Campanella was hospitalized at the time of the vote, preventing him from attending and prompting the submission of his vote by proxy. As chair, Williams’ strict by-the-letter-of-the-law interpretation carried the day and Hodges was denied Cooperstown despite having 11 of 15 counted votes in his favor.

Williams, who voted against Hodges, argued that he was only being principled in following the rules. His “principled” approach looks rather hollow when his insistent lobbying for former teammates is considered. Williams was known to talk up the candidacies of Hall of Pretty Good players Dom DiMaggio and Johnny Pesky. Neither made it to the Hall and Williams showed himself as a partisan rather than a capable leader.

You know what’s great? 70 Years later I am collecting a set of baseball cards that includes Gil Hodges but omits Williams.

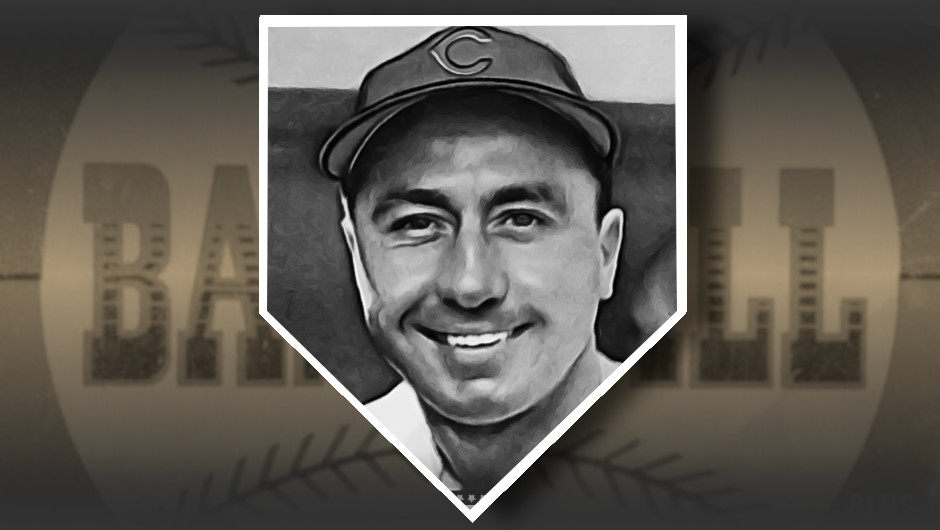

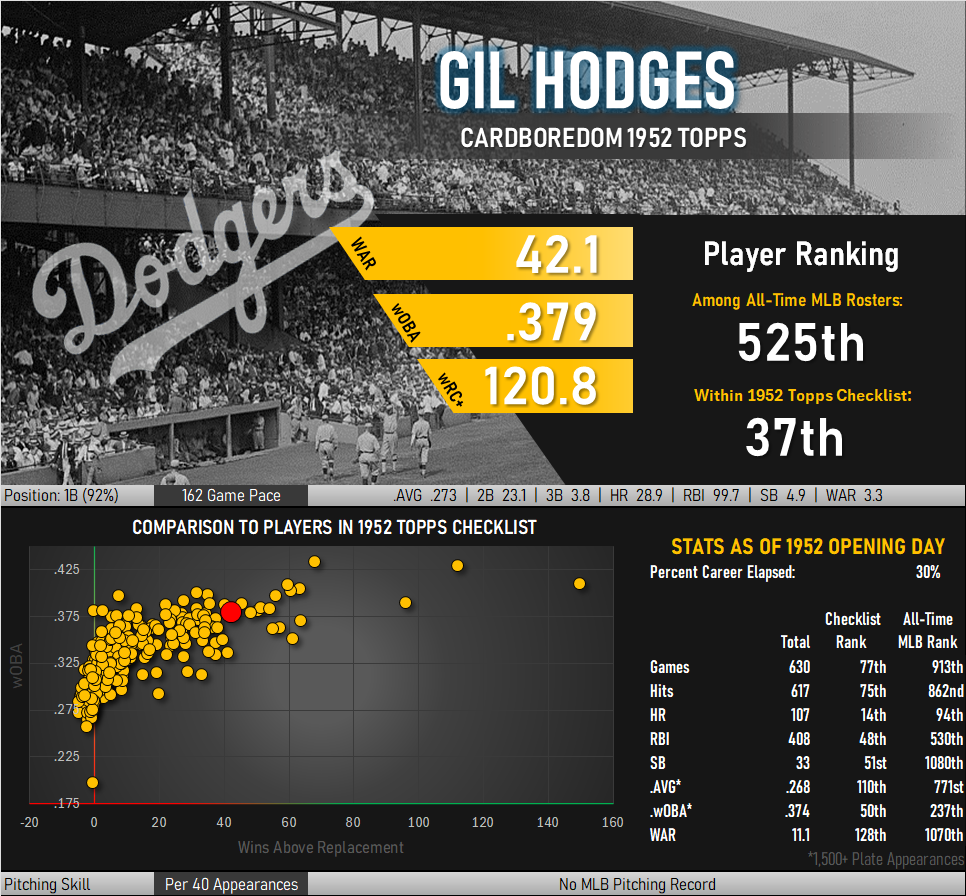

1952 Topps #36 Gil Hodges

This is the first 1952 “star” that I added to my set. The 200 lb. Hodges looks deceptively small in this photo, hiding behind the very wide nameplate in a loose-fitting uniform. He may have been the strongest player on the team. The creases in the card are much more apparent in the photo than when the card is viewed in person.