One does not usually associate weapons of mass destruction with the friendly neighborhood milkman. While the milkman typically also does not have much to do with baseball, a ballplayer known as “Milkman Jim” somehow became inseparable from the game.

Jim Turner grew up on a Tennessee dairy farm. Like many athletes of the period, he worked during the offseason and was essential to keeping the milk flowing at the family business. Having fallback employment looked wise, as Turner played 14 years in depression-era minor leagues before facing his first big league batter.

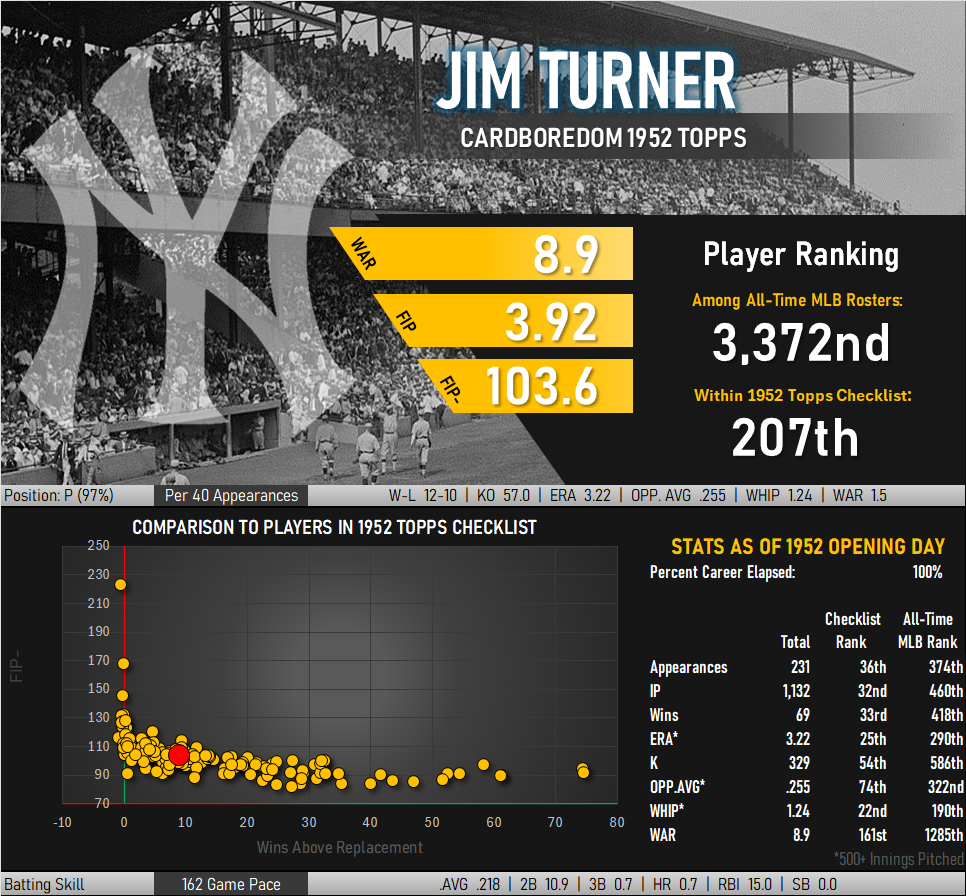

He debuted at age 33 in 1937 and promptly won 20 games, helped by an excellent ability to locate pitches. Turner did not have flashy ability, but that control was good enough to keep at the top level of the sport for another decade. He finished his MLB tenure with fairly average career stats and was promptly tasked with teaching control to upcoming minor league prospects. The Yankees, with which he had won a pair of championships, soon brought him up to the parent club to impart his technique to newcomers like Whitey Ford.

By the time his MLB-level career was over, the 33-year-old rookie’s career had spanned 51 full seasons.

Accidentally Going Nuclear

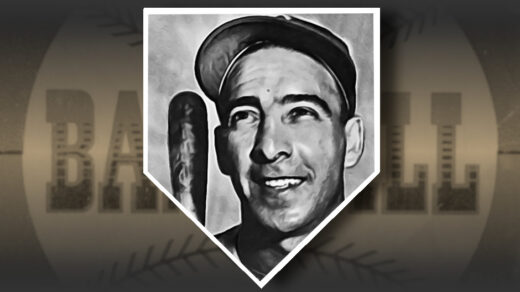

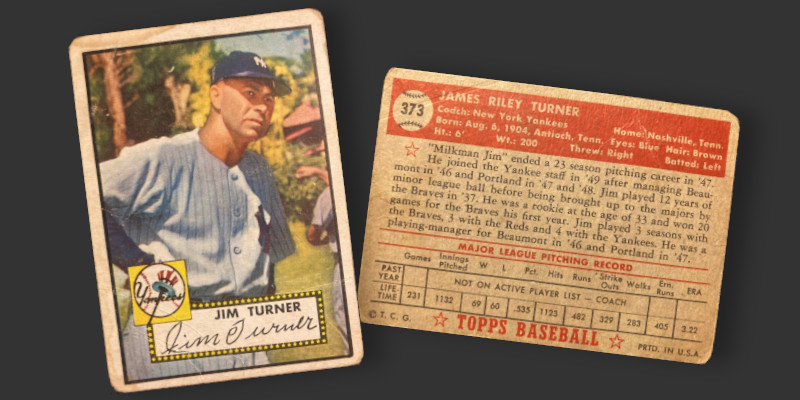

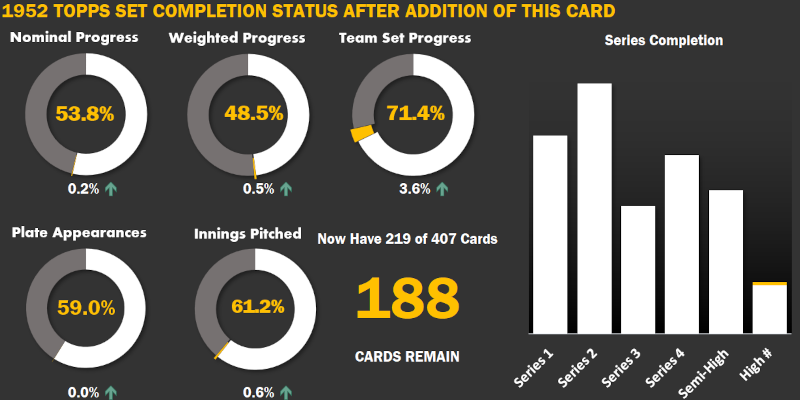

It should be clear by now that Jim Turner was an interesting player and coach, but not one that collectors are going to stress about how to obtain his cards. He appeared in only a half dozen issues during his playing days, several of which were of the minor league variety. Turner’s claim to hobby fame is his appearance as a Yankee pitching coach in the scarce ’52 Topps high number series.

I came across this low-grade example in an online auction. There were creases, round corners, as well as water damage present. The current bid was $23.33 with a few hours to go, a price that would still qualify as a steal after accounting for the “Yankee tax” of any similarly off-grade card of this series. I planned to throw out a bid a little over $40, hoping to land it while figuring current market conditions would take it a bit beyond this level. Rather than fully typing out my bid, I highlighted the leading “2” in the price and replaced it with a “4” before hitting submit and closing down my browser. Little did I realize I had not overwritten the 2, but had instead added a 4 in the middle of the price. My max bid was officially recorded as $243.33!

No sane person would pay this much for such a damaged version of this card, let alone the multiple crazies it would take to push the bidding up to this level. I had inadvertently entered what is known as a “nuclear” bid. Such a practice is usually employed by collectors who want to make absolutely sure they win an auction and are willing to pay above market rates to ensure success. The problem with a nuclear strategy is one of mutually assured destruction: The bid is put in place with the expectation that no other collector could be as reckless to offer so much. When two bidders go nuclear at the same time things can quickly get out of hand.

I woke up the next morning and was greeted by a notification that I was the high bidder. Fantastic! I must have crossed off a high number Yankees card from my list for somewhere around $40. Reading further, I was surprised to see a request to remit $172.41 for the card.

After recovering from the surprise of getting sucker punched in the wallet, I reviewed the bidding history and owned up to my mistake. I paid for the card and received it shortly afterward, stowing it away with a newfound appreciation for nuclear restraint among collectors.

Fun Fact: The biographical text on Turner’s 1952 Topps card states he won 20 games for the Braves in 1937. The team was actually called the Bees at that time, part of a short-lived rebranding that even Topps didn’t want to remember.