Mickey Harris made a name for himself on the pitcher’s mound, partly through the skill of his throwing arm and partly through telling others about that arm. That self confidence got him into more than a few “Oh yeah? Prove it” moments and ultimately resulted in a spot in the starting rotation for the Boston Red Sox in the early 1940s.

The needs of World War II called Harris away from the green of Fenway Park for four years of guarding the Panama Canal from aerial bombardment. While of strategic importance to the Allied war effort, Panama did not see any fighting. It did, however, host a tremendous amount of baseball and the Boston hurler quickly found himself as one of the more accomplished men on the ballfield. At the opening of his first “season” of playing Army baseball he threw a perfect game. Three months later he was stateside in a military exhibition game against the American League All-Star Team. He spent the next four years rotating between a pitcher’s mound and an anti-aircraft battery.

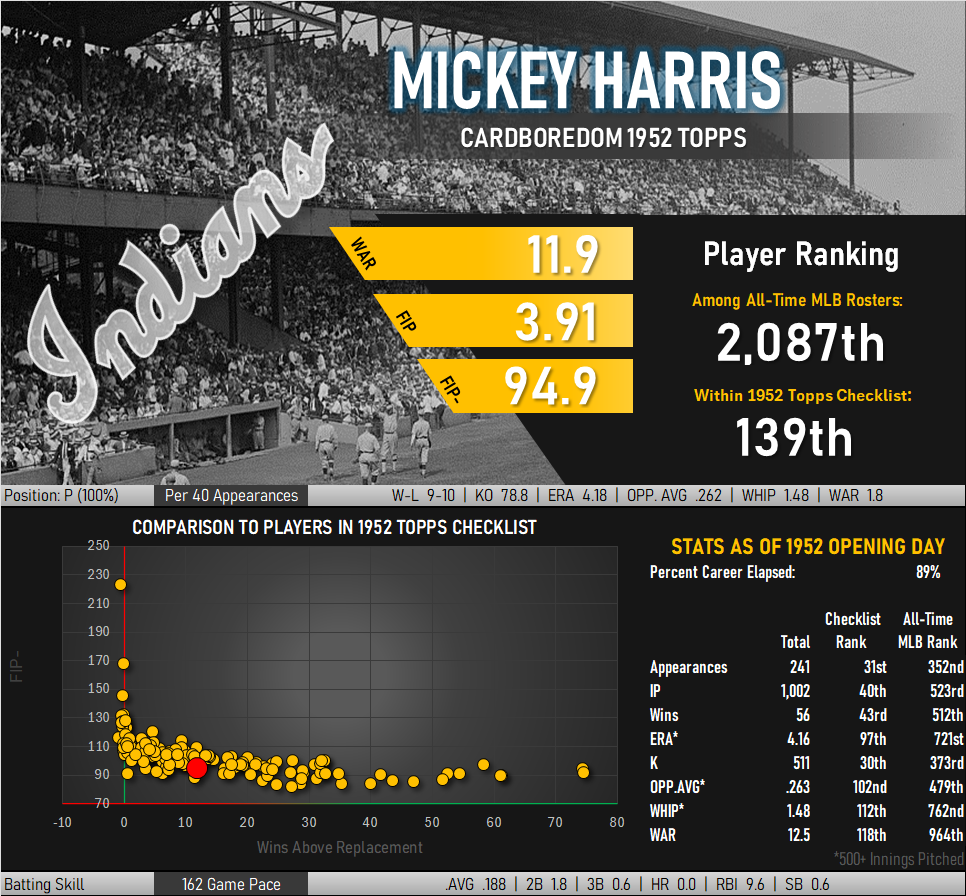

Harris injured his throwing arm in 1943 but seemed to have worked it back into shape by the time of his return to the Red Sox in 1946. He threw more than 200 innings while going 17-9 with a 3.64 ERA and making the All-Star team, all on the way to bringing the Red Sox to the World Series. That year is generally seen as his best, though some underlying stats reveal that injury may have had more of an impact than initially thought.

His 1941 campaign had seen Harris post an 8-14 record, so the jump to 17-9 with a chance at the title was generally seen as a big step up. It is worth noting the the Boston team of 1941, despite having Ted Williams hit .406, was somewhat lacking in offense. Harris’ underlying metrics show him to have been a much better pitcher in ’41 than in his ’46 return.

| Category | 1941 | 1946 |

|---|---|---|

| ERA | 3.25 | 3.64 |

| FIP- | 79 | 94 |

| HR / 9 IP | 0.28 | 0.73 |

| H / 9 IP | 8.8 | 9.5 |

| Opponents’ Average | .246 | .263 |

Harris’ arm began to weigh on his performance as 1946 progressed. His decline continued in 1947 and kept rolling in a southerly direction, prompting Boston management to trade him to the Washington Senators for Walt Masterson in 1949.

Senators’ manager Bucky Harris (no relation) had seen Harris pitch while serving a previous stint as the manager of the New York Yankees. Hired by Washington for the 1950 season, he immediately converted the overtaxed arm of the team’s newest acquisition into a relief role. Harris received accolades for his performance in 1950, a year in which baseball suddenly became enthralled with relievers. Each of Harris’ 1952 baseball cards mention the fact that he led the American League in appearances in 1950, the same year that National League reliever (and appearances leader) Jim Konstanty won the NL MVP Award. Harris did okay in this role for two years, but really wasn’t anything other than average by this point.

The One Inning Job Interview

Harris started the 1952 season as a relief pitcher, stepping out of the bullpen for an inning of mop-up duty in the losing end of an 8-2 game. The game, taking place on April 17, saw him retire the Red Sox’s Don Lenhardt on a fly to center. Walt Dropo returned fire with a solo home run before Harris was able to induce Faye Throneberry and Jim Piersall to follow the example of Lenhardt with pop flies. The final score ended at 9-2 with Harris having no impact on the game.

Still, he had not really been brought in to stop the Red Sox from winning (it was too late for that). The family controlling the Senators was looking for cash and needed an excuse to place his contract on the waiver wire. The Cleveland Indians, who had seen him pitch on their home field in his 1942 All-Star exhibition game, paid $10,000 for his contract and promptly slotted him into the bullpen for the remainder of the 1952 season.

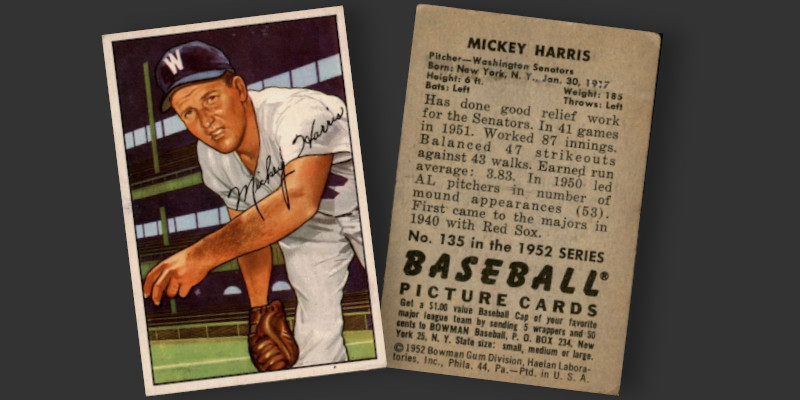

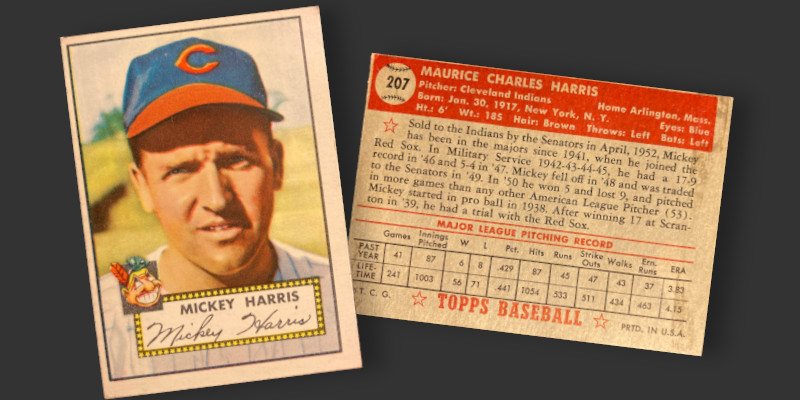

Mickey Harris’ 1952 Topps Card

In my 1952 Topps collection is a seemingly pack fresh example of the set’s Mickey Harris card. Attesting to this is the presence on the card back of wax residue from the wrapper in which it was originally packaged.

Fresh off the press is an apt way to think of this card, as the biographical text leads off with the news that Harris was “sold to the Indians by the Senators in April, 1952.” As a collector who first became acquainted with baseball cards in the heyday of Traded and Update sets, this stands out. Card manufacturer checklists were usually set in stone at the outset of the season due to operational demands decades before my 1990 introduction to the hobby. Topps was different in 1952, with lead producer Sy Berger trying to make the firm’s cards everything its rivals wished they could be. One of those improvements was having the most up to date rosters.

Harris’ card appears in Topps’ fourth series, complete with Washington pinstripes on his jersey and an artificially vibrant Cleveland ballcap. News of the pitcher’s sale to Cleveland broke in late April, indicating this series was not even off the drawing board until well into May or June. Other player movements within the Washington roster at this period were reflected in fifth and sixth series cards while those issued in earlier series reflected pre-transaction team affiliations.

Regardless of the authenticity of his cap, Harris was being depicted for the final time on cardboard in his baseball career. After joining the team in April he pitched in 29 games across 46 ⅔ innings and ended the season with a 3-0 record and a 4.63 ERA. Cleveland returned their recently acquired reliever to the waiver wire. Finding no takers, he was released at the outset of the 1953 season.