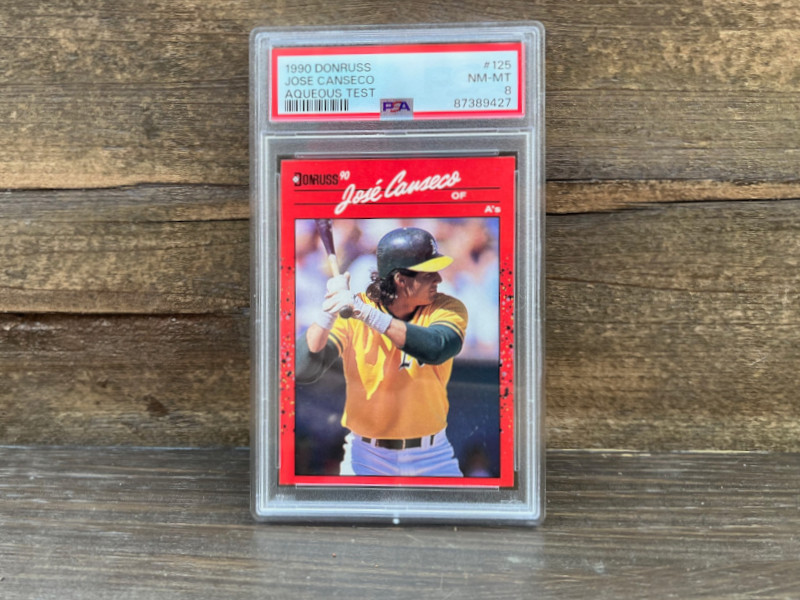

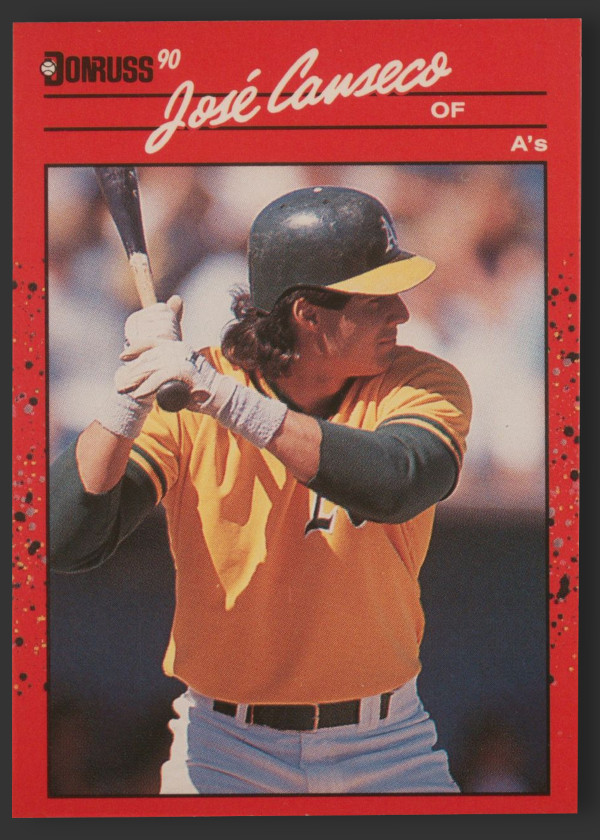

In January I was ecstatic to come across the cast-offs from an opened pack of 1990 Donruss baseball cards. A collector had opened a 15-card wax pack and pulled out a fairly well-stacked assortment of cards. Greg Maddux was front and center. A Tony Gwynn MVP was found peeking out between a bunch of commons. Barry Larkin was there too, wearing a red and white uniform on a very red and white baseball card. There was even this Jose Canseco card, which I quickly tried to add to my collection.

I can already hear the groans from readers. Anyone can lay their hands on a dozen of any player’s 1990 Donruss card at a moment’s notice. The production of somewhere close to five billion cards probably instigated a worldwide shortage of red ink. A highly stylized script made reading player names a chore. I’m pretty sure I marched into my first day of third grade with a Trapper Keeper bearing the exact same speckled lava pattern as these cards’ borders. The checklist was the largest put out in Donruss’ first decade of production and numerous errors were missed by the manufacturer during the proofing process. Aside from the Diamond Kings and Rated Rookies, the subsets are pretty bad. Every pack even came with those Carl Yastrzemski puzzle pieces nobody seemed to want.

In brief, there is no shortage of collectors that will instantly dismiss these cards. Decades later, and despite these cards being as old today as 1956 Topps was back in 1990, hobbyists looking to get rid of duplicates often find they cannot even give them away. These cards have always been inexpensive, a key selling point for a third grader in the 1990s looking to build a collection. They had an MSRP of $0.45 per pack, but the sheer number of wax boxes rolling out of Donruss’ facility quickly sent 36-count boxes of packs down to the $5.00 range, or about a penny per card. No matter how scarce the pickings were at a ’90s card show, I always knew I could come home with a couple unopened boxes of these cards for the cost of mowing a neighbor’s lawn for an hour.

That said, I actually like the set. Most major issues are lucky to have 3-4 good players make their debut. This checklist includes a dozen recurring All-Star level rookies. The bright red borders stand out from every other major card issue of the past decade and have an even greater visual impact when viewed in a 9-page binder layout. Like 1972 Topps, the cards feature loud designs that somehow come across as era appropriate. If Donruss had shown more care in the proofing process and reduced production by a couple orders of magnitude I venture that this would have become an instant classic. Imagine a collecting world in which 1990 Donruss was actually challenging to find.

1990 Donruss and its 1989 Origins

So why, as I type this in recovery from (non-Donruss induced) eye surgery, am I so happy to add this card to my collection? It turns out this card from one of the most overproduced sets of all time is also one of the rarest and mysterious cards produced in the junk wax era. The folks at Donruss never intended it to be in my collection and it is all Upper Deck’s fault.

The end of junk wax was set in motion with the arrival of Upper Deck’s landmark 1989 baseball cards. The hobby had not seen such a well-received design in years and seemingly every area of complaint had been addressed by the design team. Photos were better curated. Anti-counterfeiting holograms were on every card. Foil wrappers significantly reduced the ability to search and reseal packs. The cardstock was on a different level than the competition, standing out with brilliant white borders on both sides and a glossy finish brought to the presses by the expertise of Orbis Graphics, printers of magazines such as Architectural Digest.

Importantly, Upper Deck was selling out its 1989 print run and doing so at a wholesale price 20% above Donruss’ $0.45/pack suggested retail price. Secondary pricing on Dealernet revealed a market that could absorb markups triple the newcomer’s already aggressive price. Donruss executives were rightly scared. They were in a volume business that was facing the margin crushing double impact of lower volume for their own wares and a the task of selling second-rate product that could only weakly compete on reduced prices. They had to do something and needed to implement improvements fast.

In late summer 1989 Donruss’ production team was already well into the process of bringing the firm’s bright red 1990 cards to market. Production was slated to begin as soon as the books closed on the 1989 MLB season and a rapid-fire proofing process could be completed. The basic designs was already laid out, photographs had been acquired, and the checklist was largely set. Upper Deck’s surprise success in the final days of summer sounded internal alarms too late to upgrade the coming year’s product. The Donruss cards of 1990 would have to go out as originally planned, but that didn’t preclude the company from using some of these as test subjects for planned upgrades.

Everything that set apart Upper Deck was broken down and examined by its competitors. Future releases would obviously need to emphasize the best output of photographer networks. Alternative packaging materials would be explored, leading Donruss to ditch wax packs for foil a few years later. Cardstock would need to be improved, as would the printing techniques that would determine how improvements translated to the new materials.

One of the attributes that was studied in detail was the gloss finish covering the surface of each card. Orbis achieved this effect and its subsequent visual and tactile improvements through the use of aqueous coatings, a newer technology than the standard ultraviolet finishes employed in the trading card industry. Prior to Upper Deck, card surfaces were usually preserved under a resin-based gloss coat that solidified when exposed to UV light. These UV finishes were popular because they cured quickly, allowing for rapid production of cards that needed little time to dry. UV coated cardboard tended to yellow a bit over time, a side effect most easily seen in older Topps Tiffany cards. Aqueous coatings offered a non-yellowing alternative. As the name implies, these were water based and did not fully set until the water had fully evaporated. Evaporation can be accelerated through the introduction of jets of hot air and manipulation of environmental conditions in the production facility, but large scale employment of the technique would require significant changes in production line design and an expansion in floorspace dedicated to the curing process. Increased production time per card and burdens on already stretched manufacturing capacity promised to only increase the production cost of each improved card. Donruss’ desire was to catch up with whatever allowed Upper Deck to charge premium prices for a premium product, and any potential increases in collector demand for its improved cards and would have to be weighed against added production costs.

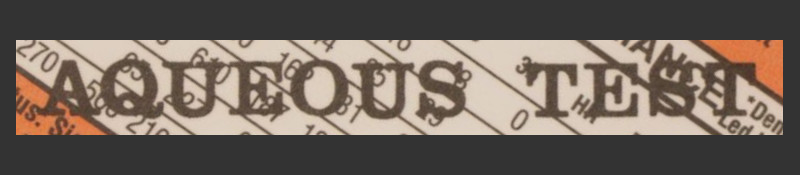

Donruss’ ad-hoc R&D team set to work creating a small run of cards using Upper Deck’s alien technology. Plates for a pair of 132-card sheets were requisitioned for the project and modified to reflect their status as test subjects. A large, all-caps “AQUEOUS TEST” was emblazoned at an angle across the back of each card to render them readily identifiable.

An unknown quantity of these cards were printed to test various aspects of the process. How fast could the card stock be run through the machinery under new process? Exactly how long did it take the inks to achieve a full cure? Did they look better or worse than the standard UV-coated versions?

Some cards were pulled and subjected to abrasive tests. Cards were rubbed against each other in special testing equipment and subjected to a glossmeter to determine how long the coatings would remain intact. Were they even strong enough to withstand a packaging and shipping process that would see them jostled against each other inside wax and cello packs?

Presumably these tests yielded some usable information, as the next summer the company repurposed its Leaf brand as a premium product to compete directly with Upper Deck. A year and a half later many of the improvements, aqueous printing included, were brought to bear with Donruss’ revamped 1992 edition.

1990 Donruss and Things That Should Not Exist

At the conclusion of the testing process in late 1989, Donruss did whatever it is that manufacturers do with the remains of internal development programs. The cards that survived the tests were wrapped like any others and tucked away without clear instructions as to what should happen to them. The R&D team moved on to perfecting the upcoming 1990 Leaf release, tackling the introduction of serial numbers on Elite inserts, and experimenting with how to best apply metallic foil to cardboard surfaces.

By 1996 the time of junk wax had passed and card manufacturers were scrambling to keep red ink of a different sort from encroaching on their businesses. That year, Donruss’ corporate parent, Huhtamaki, sold all its sports card properties to Pinnacle Brands. Debt financing for the $41 million purchase price and continued sluggish sales in an oversaturated market combined to force Pinnacle to seek bankruptcy protection in 1998. The company lost its MLB license during the restructuring and much of the firm’s sports card related personnel left at this time.

In all the confusion that accompanies creditor committees and asset disposals, a lot of surplus baseball cards were removed from the premises of Donruss’ Memphis, Tennessee offices. Obscure items tucked away in offices did not seem to be put to any formal sale process. These were not seen as being particularly valuable and my first inclination is to assume that the cost of restructuring lawyers billing in six-minute increments outweighed any potential recovery from an item-by-item sale of whatever boxes of junk wax were still present on office shelves. Disposal of these items may have been delegated to local managers or left to the judgement of each person walking out of the building. By whatever means were employed, offices were cleaned out with many outgoing employees taking home these last cardboard reminders of the prior decade.

Within a year of the bankruptcy the phone rang on a Saturday morning at Season Ticket, the sports card shop run by hobby veteran Chandy Greenholt in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The caller said he was a former packaging director at Donruss and was looking to sell 20 boxes of unopened cards produced between 1988 and 1992. Given the limited demand for much of these products, a deal was reached in which Greenholt acquired the 20-box lot in exchange for paying full collector price for the lone box of premium 1990 Leaf packs present in the bundle. The cards were dropped off the same afternoon, the seller paid, and the cards set aside in a back room to be inventoried at a convenient time. Greenholt left the store to take up his usual position as coach on the sidelines of a youth soccer league and put the cards out of mind.

Returning to the store, he began to take stock of what had come into the shop. The 1990 Leaf box was duly set aside to be sold in order to recover his costs. There were 1988 through 1992 Donruss wax boxes with a heavy emphasis on the latter three years of the run. Also included were three non-descript white boxes bearing Donruss’ Canadian wordmark and accompanied by a brief, similarly adorned intracompany memo. One box contained 1990 Donruss wax packs and the other two were filled with cello packs from the same release. Greenholt opened one of the wax packs and found himself faced not with the familiar red borders he expected, but rather an odd assortment of two-faced ’90 Donruss cards featuring alternating blue or white borders. These were part of an ultra-scarce color test conducted at Donruss and someone had actually cut them up and put them into packs.

As a personal collector of test issues, he now realized these white boxes contained something special. Turning his attention to the boxes containing cello packs, he could see the usual red borders starting back at him through clear wrapping. Greenholt opened a pack and sifted through the seemingly normal cards. Seeing nothing amiss, he flipped them over. Emblazoned across the reverse of each card as the large “AQUEOUS TEST” banner. Pack after pack followed the same pattern: Normal looking 1990 Donruss cards with large lettering blotting out large swathes of text on the back.

Greenholt began to sell some of these cards, publicizing small numbers of them as part of his usual print advertising. The 1,728* cards contained in his pair of cello boxes briefly represented the total known quantity of cards in existence, prompting a few collectors to take notice.

*Regular Donruss boxes in this configuration yielded 864 base and bonus cards, 48 puzzle sections, and 24 Grand Slammer insert cards. I have not seen any reference to inserts or puzzle pieces having been included in the test packs and am assuming each pack only contained 36 test cards.

For the First Time in 50 Years, A Mystery

One thing that has fascinated me about the history of baseball cards is how checklists have come together. Many manufacturers release lists of all the cards in a particular release, making it easy to benchmark your own collection’s completeness. Others, particularly early in hobby history, produced such large quantities of cards that it was relatively easy to determine the size of a set after opening a few boxes.

Sometimes these simple clues are not present. Leaf Gum Company, which was eventually absorbed into Donruss, produced a popular set of cards in 1949. Although the cards were numbered on the back, no checklist was issued and the company skip-numbered its product. The back of these cards sometimes contained advertisements for a binder in which the collectors could display their set. The album, unhelpfully, was advertised as being able to hold 168 different cards while only 98 appear to have been released. Of these, half were distributed in such small quantities in a few select regions that collectors were unsure of exactly which card numbers even existed. Jim Beckett, the longtime card dealer and force behind the eponymous Beckett Baseball Card Monthly once said in an interview that collectors really didn’t know the full extent of the checklist until the early 1970s, more than two decades after the cards’ release.

That kind of information scarcity and extended timeline for cracking the checklist attracted quite a following to the Leaf issue. Like a crossword puzzle consisting only of clues with no accompanying grid to guide solvers, the mystery attracted a flock of tenacious collectors. They shared information, traded cards, and worked together to figure out the extent of what exactly had been printed. That same kind of cardboard sleuthing DNA jumped back into action when these cards began trickling out of Greenholt’s shop.

For starters, the regular 1990 Donruss checklist was comprised of 716 cards in the checklist and another 26 bonus cards recognizing an MVP for each team. The cards found in Greenholt’s boxes were only found with numbers between 1-283 with a few of the MVP bonus cards present. Did these represent the full extent of the test issue? Were they skip numbered, or did this indicate additional unknown cards were waiting to be found? Why were some cards more prevalent than others?

Speculation about the cards began to build, first among die-hard player collectors in search of one last rarity to chase, and then among a slowly growing group seeking a profound set-building challenge. The first order of business was determining how many cards comprised the set. Under Donruss’ production setup of the time, cards were printed on 132-count sheets that would be cut up for collation into packs. Six sheets could accommodate a full set as well as various bonus issues such as the MVP series. All known cards with the aqueous text matched up with cards that had appeared on the first two sheets. Cards were largely laid out in numerical order, though a partial sampling of Diamond Kings, Rated Rookies, and MVPs were scattered among these sheets. The lack of any card number outside of these two printing forms led collectors to conclude the aqueous test was only applied to the 264 cards comprising these sheets.

Greenholt had two complete cello boxes of the cards. With 24 packs per box and 36 cards per pack, this yielded 1,728 cards. Dividing this total by the 132-cards printed on a sheet implied ~13 sheets had been employed in production, yielding an average of just over 6 of each individual card. When matching the sheets up against Greenholt’s inventory, it became apparent that the cards on one sheet were more plentiful than the other. From this came initial hobby theories that as few as five of each aqueous card existed, generating further excitement among those seeking truly difficult to find modern cards. Add in the possibility that some players had been short-changed in the process and one can imagine the predicament of player collectors with a leaning towards perfectionism.

But Wait, There’s More!

As a long-tenured dealer who was deeply plugged into the hobby, Greenholt soon knew he was not in sole possession of the aqueous market. He recounted that at around this time he had become aware of another dealer in the Milwaukee area with at least one similar test box and possibly a second. Their inventories differed in the availability of certain cards, partially evening out the difference in quantities available from the first and second sheets.

The Standard Catalog of Baseball Cards, an exhaustive tabulation of just about anything considered to be an “official” baseball card, began listing the cards in the early 2000s. Their first description included a note that “approximately 2,000-2,500 cards in total are known, with only part of the ’90D checklist represented in the test issue. As few as one specimen each are known for some cards, while a half-dozen or more of others are recorded.” This estimate of just over 2,500 for the entire print run is in line with the idea of 3 cello boxes containing the entire quantity of cards produced. An even distribution of boxes between Greenholt and his Wisconsin-based counterpart would bring total production to 3,456 cards with an average of 13 examples of each player. There were clearly more cards out there than what was claimed in the Standard Catalog, but not so much as to make them easy to find.

While the reference book also warned that the checklist was possibly incomplete, set collectors were already well on their way to developing a consensus. Like the legendary 1949 Leaf set, this checklist was taking on a life of its own. More than a decade passed since the emergence of these cards before a final checklist was settled upon.

| Subset | Methodology | Card Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| Base Cards | 236 Cards In Sequence | 48-283 |

| Diamond Kings | 9 Skip Numbered Cards | 1, 3, 6, 9, 11, 14, 16, 18, 22 |

| Rated Rookies | 9 Skip Numbered Cards | 24, 28-35 |

| Team MVPs | 10 Cards In Sequence | BC1-BC10 |

Much of the work in tracking down these cards was taken on by Bob Fisk, a highly accomplished collector who also happens to have assembled one of the most impressive ’49 Leaf sets in existence. He was instrumental in getting PSA to begin grading Aqueous cards in 2009 and creating a set registry for the newly discovered issue the same year. To date he is the only collector known to have completed the ’90 Donruss Aqueous set. Bob happily shares scans of his cards in his registry listing and was highlighted by incoming Collectors, Inc. president Nat Turner in the 2020 Registry Awards for assembling the Best Modern Baseball Set of the Year. Kudos Bob!

Growing Populations

Around the time that Fisk was getting the set registry up and running it was apparent that at least some cards were available in greater numbers than the 5 or 10 copies that captured whatever public imagination existed for the set. Some card numbers remained much more difficult to track down than others and the reason was still shrouded in mystery. Had these missing cards been destroyed in the name of 1989’s card-manufacturing science? Were the two sheets produced in different quantities, effectively resulting in two different print runs? Or, of even greater interest to collectors now on high alert for these cards, was there another undiscovered cache waiting to be found?

In late 2011 a rash of eBay alerts began spitting out new search results. Some of the (relatively) easier to find card numbers were appearing on the auction platform and were coming from a seller not previously associated with either of the two original dealer sources. A couple of new boxes had been discovered, and unlike the others seen before they contained cards wrapped in more traditional wax wrappers. Each box yielded 540 cards from three dozen 15-count packs. The packs again bore hints of Donruss’ Canadian unit as the wrappers stated each pack was to contain only 10 cards, the standard unit sales size for that country’s cards.

The following spring a fourth seller appeared with a different strategy for moving his cards. Like the offerings of the 2011 seller, these cards were also wrapped as Canadian wax packs. A small number of unopened packs were put up for sale. When those sold strongly a second batch was offered, and then a third. Collectors realized this was more than just a handful of packs coming to market, but those opening the cards found many of the “missing” numbers that had previously been so difficult to locate. The quantity of packs offered and sold increased as collectors began to accept them as legitimate and good source of previously harder to find card numbers. Multiple boxes were broken down and sold in this manner. A sale of four wax boxes worth of cards added to all previously known sales would take total Aqueous production to 6,696 cards or about 25 of each player. This closely approximates the total graded population of some of the most graded names, creating a plausible estimate for the total print run. No new finds of these cards have emerged in the dozen years intervening this discovery.

A Wild Aqueous Appears!

It is against this backdrop that I bring my own card collection into the conversation. I am primarily a set collector with a focus on a handful of insane set building projects. The Aqueous set is one of those projects that I would love to tackle, but I cannot justify the (probably) impossible task of finding all of these cards when there are other cards I would rather have on an individual basis.

When I am not adding cards to one of my five in-progress (non-Aqueous) sets, I am looking for harder to find Jose Canseco cards. He was my favorite player growing up and I have long admired what some of his more dedicated player collectors have assembled. While I had his ’93 Finest Refractor, ’91 Donruss Elite, and other key cards, there were always a few ultra-rarities I assumed would either never surface or be quickly scooped up by these hardcore collectors. The 1990 Aqueous Test card was among these and sat atop my list of seemingly impossible non-1/1 cards. Tanner Jones, perhaps the most enthusiastic of these super-collectors, once ranked it among his top 10 junk wax cards of all time.

Imagine my surprise when a collector appeared on a forum looking to sell the opened contents of one of the wax packs pieced out a decade ago. Canseco wasn’t mentioned in the post’s title, but the card could clearly be seen in the attached pictures. Those faster than me had already balked at the asking price for the 15-card lot, prompting the seller to start selling cards on an individual basis. I took a good look at the pictures, made an offer, and soon had the card on speeding towards me through the postal system.

Trust (but Verify)

This was probably my one shot at landing an Aqueous Canseco card. Only a handful of examples are known to exist, with two in the hands of the most voracious pair of Canseco collectors out there and a third sitting in the only known complete set. Those cards likely will not be seeing the light of day for decades. Several other Canseco collectors frequent the same online forum and would soon be throwing out offers of their own. How could I determine if this was a legit card?

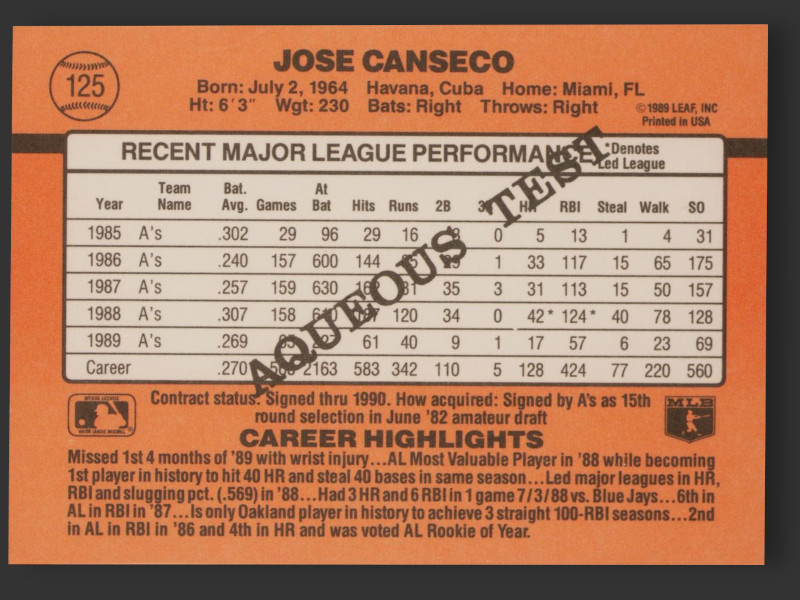

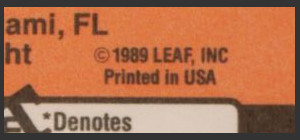

For starters, every card in the group came from the same sequence of card numbers found in the generally accepted Aqueous checklist. There were no cards that shouldn’t be there. Secondly, the copyright line on the back of the card reads “©1989 LEAF, INC” rather than “©1989 LEAF, INC.” No Aqueous cards have the trailing period after the abbreviation of incorporated while it is present in the majority of regular Donruss cards. While lack of a period does not confirm authenticity, it is a requisite characteristic of authentic cards.

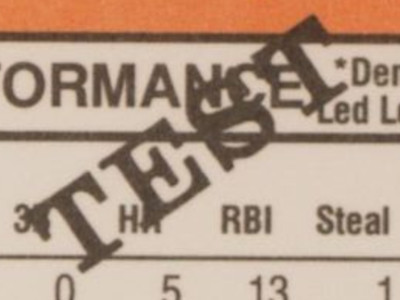

The gigantic “AQUEOUS TEST” text was clearly visible in photos. As with all other base cards in the set, the first “T” in Test partially overlapped the header for triples in the statistical table. The exact placement of the test differs from card to card, but is in precisely the same location for each specific card number in the set. I compared my card to the detailed scans published from the collections of Tanner Jones and Bob Fisk. The text and font matched perfectly.

Caution is a must with these cards, as there rarity and premium pricing combined to be profitable for those fraudulently trying to pass off fakes. One particularly egregious scammer tried to defraud collectors in 2005, selling under multiple eBay aliases and even going as far as setting up a fake website to “educate” buyers about his cards. The scheme fell apart when potential buyers looked closely at the cards. The font was wrong. The “AQUEOUS TEST” text was an ink stamp and had been applied in slightly incorrect places for each card. The seller even tried to fake cards outside of the numerical range contained on the two sheets used to create the original cards.

Donruss made, and corrected, a large number of errors in the production of its 1990 cards. Because the test cards were taken from specific sheets early in the production process, they all have the same errors as the earliest print runs. The Juan Gonzalez rookie, for example, only appears as the reverse negative variation in the test issue and depicts him erroneously batting left-handed.

Even third party authentication should be double checked against knowledge of the set. On eBay right now is a regular Juan Gonzalez card erroneously authenticated and labeled by Beckett as an Aqueous card (Serial #011329889) – there is no “AQUEOUS TEST” text appearing anywhere on the card in that slab.

Once I received my card, there remained one more test to verify authenticity. The “AQUEOUS TEST” text on the back of original cards is part of the same layer of black pigment used for all other text on the reverse. It carries the same reflection as the rest of the text under strong light and under strong magnification has no break with other black elements on the back of the card. There is no other text bleeding through these giant letters, something that would be present if one were to simply print words on top of a regular Donruss card.

Satisfied, I sent what was now the best card in my Canseco collection to PSA so that it could match the other highlights of this player collection. Only the fourth example ever graded, it will likely be the cornerstone of my small assembly of Canseco cards. I had a tremendously enjoyable time piecing together a history of a set that I had previously only had passing knowledge about. Many accounts of these cards rely on repeating information found in the earliest online discussions of the set, giving it something more of a legend that a concrete history. The cards established their hobby reputation in the early 2000s and through retellings of that legend they have only grown their hold on collectors. Locating one is not only like finding a needle in a haystack, it akin to finding a slightly different color needle in a mountain of needles. While not as rare as initially believed, the cards remain one of the toughest and most sought after of the era. Who says Junk Wax is boring?