I just might be the greatest pickleball player to ever live. I’ve never played or even watched a match, so one would be correct in placing a skeptical emphasis on the word “might.” All I have to recommend me is a general appearance of excellent physical conditioning and the absence of a pickleball record that would immediately disprove my standing in the sport. If forced to bet on my prowess on the court you would be wise in taking the under.

John Kruk, who as far as I know only excelled at baseball, famously quipped to an inquiring visitor that “I ain’t an athlete, lady. I’m a baseball player.” Despite having played more than a decade at the highest level of a major sport, he too would likely fall far short of actual top-ranked pickleball picklers.

There are, however, people who do exceptionally well in athletic competition regardless of the sport. These are the ones for whom we reserve the term “athlete,” a word evocative of all around skill rather than success within the narrow confines of a single sport.

The term comes from the Latin athleta, and it is from antiquity we find perhaps the most accomplished exemplar of the term. The Greeks religiously (literally religiously) held athletic contests every four years at Olympus as far back as 2,800 years ago. There were multiple sports in which participants could compete as well as additional regional games in the off-years. It is possible that the greatest all around athlete in recorded history took part in these contests.

Around the time the quality of Olympic competition solidified into a top-level spectacle, there emerged an athlete who began systematically destroying his opponents. A young boy from Croton entered the junior wrestling event in 540 BC and soon dominated his way to accolades as the division champ. Four years later the wrestler known as Milo grappled at the adult level. Four years after that he did the same and was declared the victor. This was repeated after another four years, then again, and again, and again with each iteration accompanied by a first place finish. Imagine a teenager winning Olympic gold at the 2000 Sydney Olympics, competing in each ensuing contest through 2024, and coming away with the gold medal in all but the ’04 games. Milo’s career was not over, as four years later he again faced off against all challengers, this time showing his age and having to settle for second place.

Milo excelled at any task requiring physicality, apparently going nearly undefeated in what amounts to a lifetime of bar bets about his strength. He challenged frustrated onlookers to pry pomegranates from his grip while he kept the fruit undamaged. He would also hold his arms outstretched while keeping foes from bending his little finger or hold his ground on a slippery surface without being knocked off by erstwhile assailants.

One would do well to think of the Greek Heracles or Roman Hercules in these situations, as there is a good deal of crossover between the legends of Milo and the demigod. It is thought that some of the myths of Heracles grew out of exaggerated tales of real life heroes, and while already widely recognized in Milo’s era, it is possible some of the later tales borrowed from Milo’s exploits. Milo played up his resemblance to Heracles in 511 BC, in which he commanded an army while carrying a club and dressed in his Olympic wreaths and a lionskin, the same outfit that Heracles wore in his own legends. Anyone that can successfully pull off being mistaken for (or even influence) the Greek personification of strength can make a claim for greatest athlete of all time.

Milo Gets Some Competition

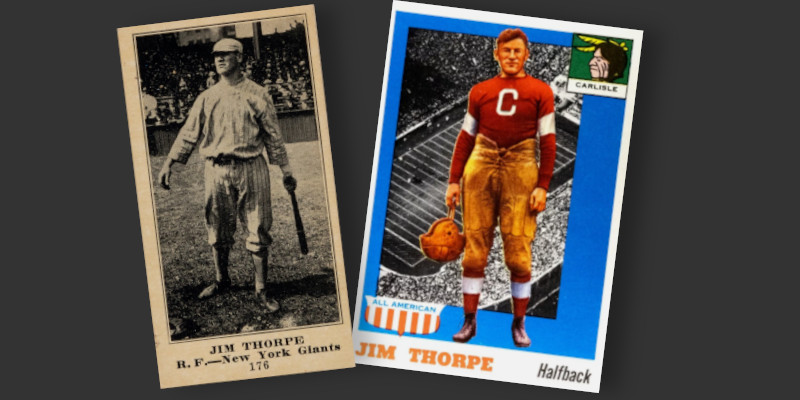

The ancient Olympics ceased near 400 AD and were revived in their modern format in the late 19th century. Spectators at the 1912 Stockholm games witnessed one of the greatest all around performances of the modern games when a Carlisle Indian Industrial School student carried multiple events with track & field gold medals. The athlete, Jim Thorpe, had walked onto the school’s track team five years earlier when on a whim and dressed in street clothes he beat the track team’s high jump mark. By the time he arrived in Stockholm, he was a top competitor in track, multiple positions in football, baseball, and ballroom dancing. He competed in every track & field category at the Olympics, taking home gold in both the multi-specialty pentathalon and decathalon. His standings are notable for several reasons: 1) He had thrown his first javelin only a few months earlier. 2) His decathalon score set an Olympic record that would stand for two decades. 3) He did this while wearing mismatched shoes of the wrong size.

Thorpe was not just at the pinnacle of amateur sports. He played both professional baseball and football, at times within the same season. He played in parts of six seasons in the National League, batting .327 in 62 games in 1919 before leaving to concentrate on football. Professional football was a bit nebulous during the early 20th century, principally consisting of semi-pro regional teams as well as “students” at various schools. Thorpe was widely acclaimed as the top force on the gridiron, both as the most accomplished practitioner of the ground game and as the most recognizable kicker in the sport. During his baseball years he toured with several semi-pro squads with most of the time spent with the Canton Bulldogs. Thorpe and his Bulldogs became inaugural members of what would become the NFL with Thorpe himself serving as both an active player and the league’s first president. Interspersed among his professional baseball and football duties were small numbers of semi-pro basketball and hockey games.

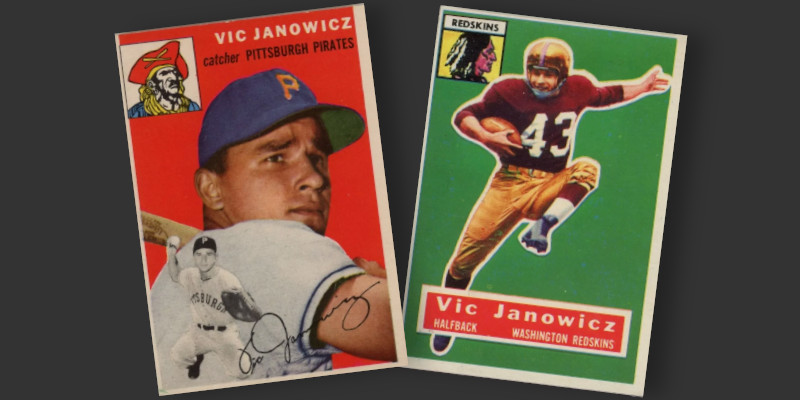

Thorpe last played in the NFL in 1926, leaving fans searching decades for anyone who could remotely approach his athleticism. A possible successor emerged near the end of Thorpe’s life when Vic Janowicz won the Heisman Trophy playing football at Ohio State. He immediately signed on to play professional baseball with the Pittsburgh Pirates before switching to football with the Washington Redskins. Like Thorpe, Janowicz’ was better at the latter sport than baseball, ranking as the league’s second highest scorer in ’55. Unfortunately, his career was prematurely ended the following year with a car crash. It would take another 30 years for a Heisman winner to bring back the idea of a multisport virtuoso.

Enter Bo Jackson, the winner of college football’s top honor in 1985. Obviously a standout football talent, he was an even better track competitor (sound familiar?) and an accomplished archer. Baseball was also a passion, though it was perhaps his third or even fourth best sport. It would prove, however, to be his escape after a bungled visit to meet with the NFL’s Tampa Bay Bucanneers erased his amateur status with the NCAA and resulted in his being declared ineligble to play baseball for the remainder of his senior year. A similar controversey resulted in Jim Thorpe’s 1912 Olympic medals being disqualified. Highly upset, Jackson let the Bucs burn their number one draft pick on him and instead signed an agreement to play baseball with the Kansas City Royals.

From there the legend grew, with Jackson famously hitting a one-handed homerun and catching a ball in the outfield before running up a vertical wall. As soon as the baseball season ended he switched to playing professional football for the Los Angeles Raiders, joining fellow Heisman winner Marcus Allen for an electrifying 1-2 running game that could only be described as Thorpe-esque. Jackson continued this back and forth athletic existence through 1991 and seemed to improve in both sports with each passing season. Jackson’s versatility became a selling point, with Nike’s marketing machine quickly transforming him into the face of everything not already covered by Michael Jordan.

Jackson was about as well known as a sports icon could get as the 1990s got underway, and pretty much anyone with a passing knowledge of the era is aware of how a severe hip injury ended his NFL career and significantly reduced the length of his time in baseball. Highlights of his exploits in both fields are readily found online, often accompanied by comments stating Jackson could have been a Hall of Famer in both sports.

Halls of Famer?

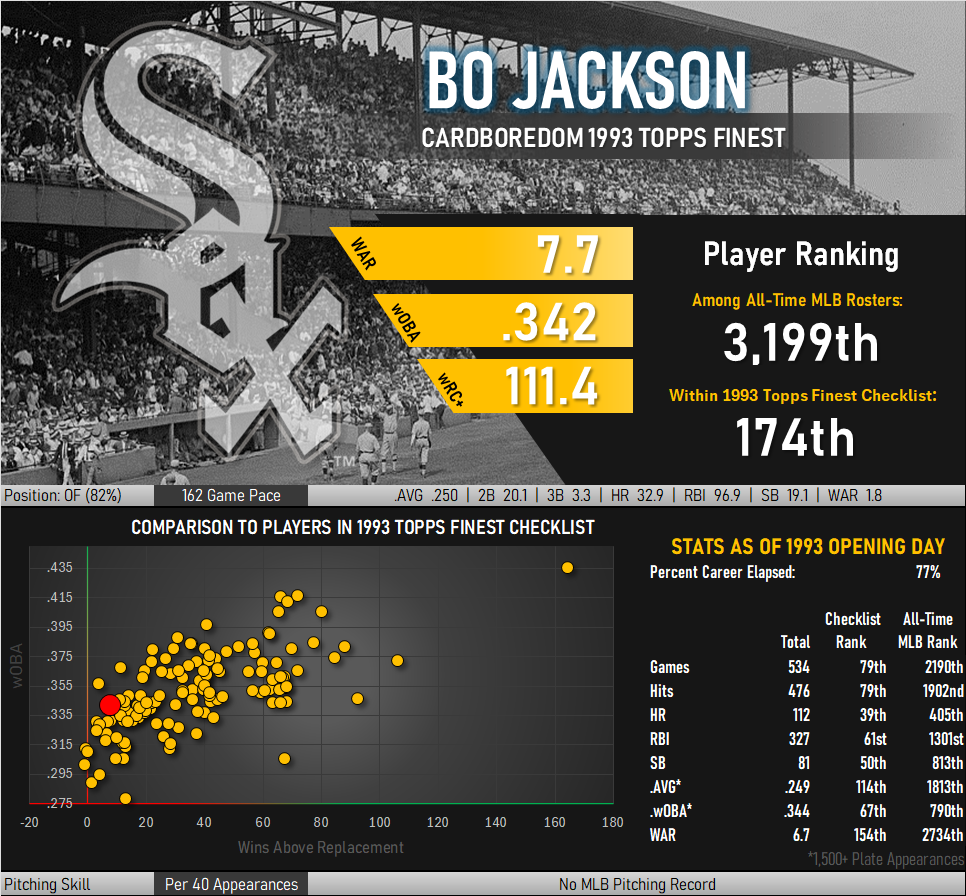

Put me down as being skeptical of Bo Jackson making it into Cooperstown on his baseball skills alone. He had all the legends, myths, and highlights of a Hall of Famer, but the actual numbers were a bit lacking in comparison to the rest of the Hall.

Take a look at how his baseball life panned out in the graphic above. Admittedly, this shows the entirety of his career and includes a substantial body of work that was put on the field after undergoing hip replacement surgery. The guy resumed crushing baseballs for several years after undergoing a major medical procedure usually associated with elderly fall victims. Clearly just looking at his actual record will not provide a serviceable estimate of a hypothetical full career.

Let’s be absurdly generous with this, giving Jackson the benefit of the doubt on several fronts. Firstly, let us assume his 1986-1990 MLB seasons stand as they are. Secondly, we make the assumption that his first two seasons suffered from rookie jitters and the difficulty of adjusting to major league pitching. Ignoring those seasons, as well as his postoperative years with the White Sox and Angels, it is assumed the rest of his career would have played out exactly equal to the average of his best three years (1988-1990). Furthermore, Jackson is assumed to play injury-free, have zero aging curve, and retire on his 40th birthday.

So what do these rosy assumptions produce?

| .AVG | H | HR | RBI | SB | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| .256 | 1,860 | 449 | 1,317 | 353 | 35.8 |

These numbers depict a guy from the Hall of Very Good. Look at how this compares against a selection of players active in the 1990s:

| NAME | .AVG | H | HR | RBI | SB | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harold Baines | .289 | 2,866 | 384 | 1,628 | 34 | 38.8 |

| Edwin Encarnacion | .260 | 1,832 | 424 | 1,261 | 61 | 35.5 |

| Jose Canseco | .266 | 1,877 | 462 | 1,407 | 200 | 42.4 |

| Steve Finley | .271 | 2,548 | 304 | 1,167 | 320 | 44.2 |

| Reggie Sanders | .267 | 1,666 | 305 | 983 | 304 | 39.8 |

| Paul Konerko | .279 | 2,340 | 439 | 1,412 | 9 | 28.1 |

| Bo Jackson (est.) | .256 | 1,860 | 449 | 1,317 | 353 | 35.8 |

Jackson’s hypothetical 400+ HRs might have got him some votes, but the rest of his numbers simply blend in with other good but not great players. Harold Baines, the de facto embodiment of a threshold Hall of Famer, clearly has the better offensive metrics. Add in the fact that even with insane speed and a fantastic arm (radar guns hitting triple digits), Jackson was generally a net negative in the field.

All of this, of course, is also built on the idea that Jackson would have continued to perform as he did in his mid-20s. Baseball players tend to peak around age 28 and then see their production fall off as they get into their 30s. Jackson falls short of Cooperstown without the weight of an aging curve dragging down his stats, a rather optimistic assumption given his history of avoiding workouts whenever possible.

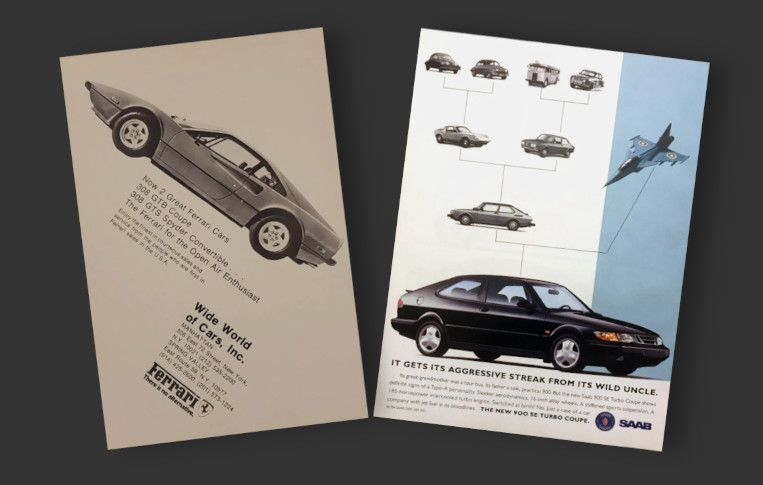

Ferrari and Saab

Let’s step back a bit. Just because two things look similar on paper doesn’t mean the have the same impact. To see this in action you need look no further than the track telemetry of two very different cars.

Ferrari is about as synonymous as one can get with racing success. The cars are noted for aesthetic design that screams “speed” as loudly as the sound of their distinctive exhaust note. Approximately 70% of the sports cars rolling out of Maranello are delivered in the firm’s trademark red paint. The cars’ use in film denotes instant recognition, becoming as much a star of the screen as the lead actors in shows like Miami Vice and Magnum P.I. The latter featured a red 308 GTS, a car that actually had a faster cousin in its 308 GTB model. A quick GTB could get you to 60 MPH in 6.7 seconds and through a quarter mile in 15.0 seconds flat.

Like many teenagers I had a poster with a red Italian sportscar on my bedroom wall. When it came time to actually lay out cash for my first car, I understandably did not drive back to the house in a red Ferrari. Instead, I purchased a blue Saab 900 hatchback. Saab automobiles sprung from roots in manufacturing Swedish fighter planes, a family history that lends itself to all kinds of oddities like an in-dash weather radio, a button to instant black out the instrument cluster, and an ignition system located in middle of the center console. It was an absolute blast to drive, but nobody ever thought of it as being on par with the Ferrari.

Here’s the amazing part: The 308 GTB and the 1995 Saab 900 Turbo Coupe both have identical 0-60 and quarter mile times. On paper they give the same performance with the Saab possibly winning a longer race due to needing fewer pit stops for fuel.

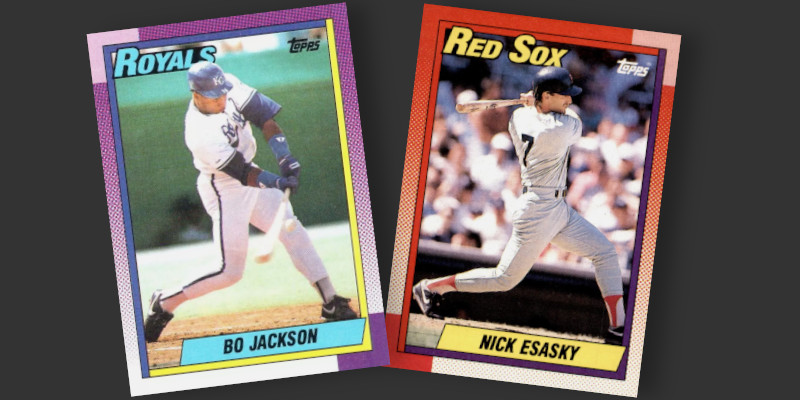

Like the Ferrari, Bo Jackson had a baseball doppelganger who looks almost identical on paper.

| Name | Games | HR | RBI | K% | .AVG | .wOBA | wRC+ | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bo Jackson | 694 | 141 | 415 | 32.0% | .250 | .342 | 111 | 7.7 |

| Nick Esasky | 810 | 122 | 427 | 23.2% | .250 | .342 | 111 | 9.3 |

Both saw their careers play out over 8 seasons in the 1980s and into the early 1990s. Each were free swingers at the plate. They produced almost identical batting averages, weighted on base and run creation metrics, and are separated by a 162-game pace of just 0.06 wins above replacement. Their careers even ended in similar fashion with injuries derailing the pair inside a 12 month period.

Bo Jackson and Nick Esasky left nearly identical statistical impacts on the record books, though every single baseball fan would still have picked Jackson for their team. That’s the true measure of his impact.

Adding Bo to My Set

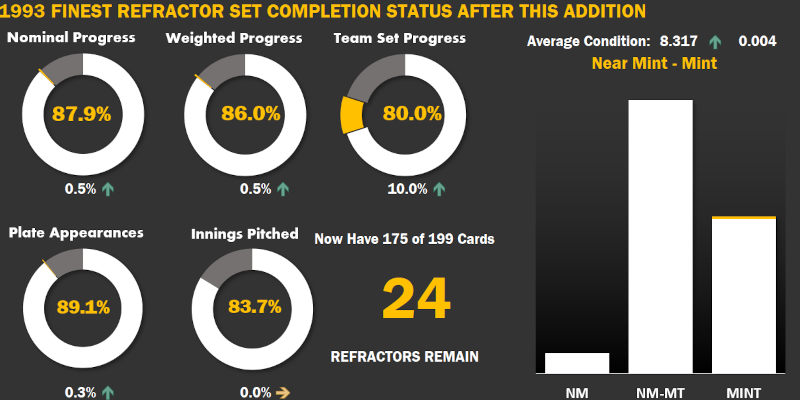

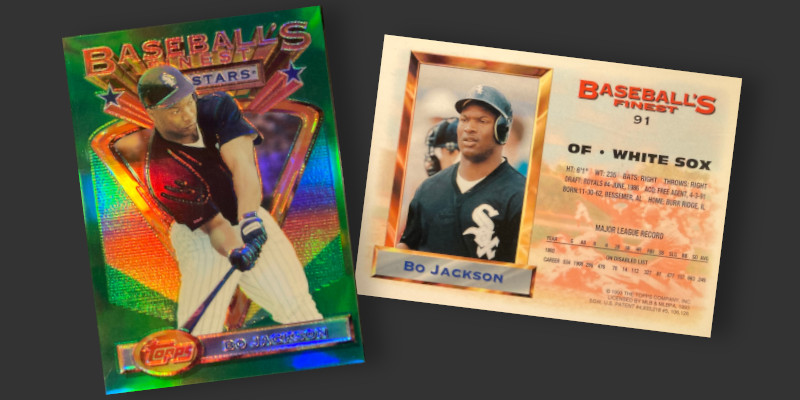

It is hard to believe that almost a quarter of Jackson’s career plate appearances came after his hip replacement. Topps was certainly excited to see Bo return, not only including him in the 1993 Finest checklist but designating him as one of the set’s 33 All-Stars. Jackson was only named to a single real life All-Star squad, taking home the game’s MVP award in 1989.

Jackson’s cards spent much of the past 30 years being ignored by collectors as they moved past his injury and onto the exciting home run races of the late 1990s. A wave of 1980s nostalgia returned in recent years, along with the added financial resources of Jackson’s most impressionable fans now entering their professional prime. Suddenly his cards were in demand.

I held off on adding Jackson to my set building project, hoping some sort of pre-COVID pricing regime would return to his cards. A 2022 trip to the Chantilly card show revealed a dealer with a beautiful example at his table, but he showed zero interest in coming down from his $600 asking price. Suffice it to say our pricing expectations were very far apart. From experience I know that amount could replace the muffler at least twice on my old Saab.

Instead, I took the boring route and waited for one to just show up online. The one now in my collection was part of a larger group purchased from a collector breaking up a full set. The good news was he had completed his project in 2017 and was listing his cards at his original cost plus whatever fees would be incurred in making the transaction happen. Combing through those past auction records and planning what to target in upcoming sales was like a real world version reading an old price guide and making actual additions to the collection based on the stale pricing data.

Buck O’Neil once summed up Jackson by tying him in with the most mythical of baseball legends. A fixture of Kansas City Monarchs lineups, O’Neil had firsthand experience with some of the greatest players to ever take the field. Despite spending nearly a century immersed in the game, O’Neil told interviewers that he only heard a distinctive crack of the bat come from three players. He told of a unique sound originating from the bats of Babe Ruth and Josh Gibson, followed by a multidecade silence. The echo of those bats returned when O’Neil heard Jackson connect with a pitch. Despite what the stats say, this story just seems to fit Bo.