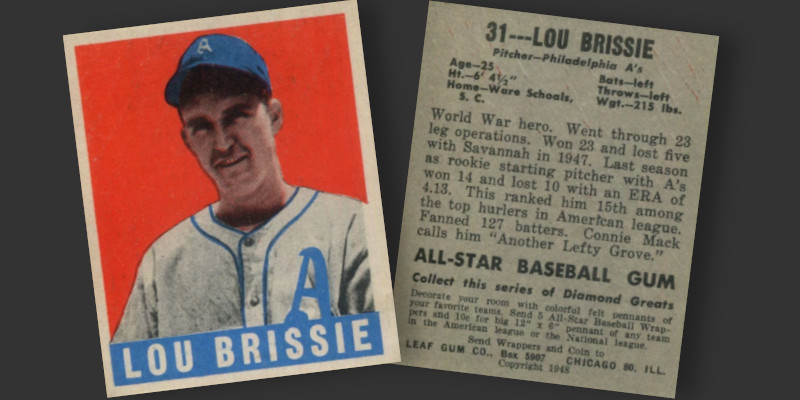

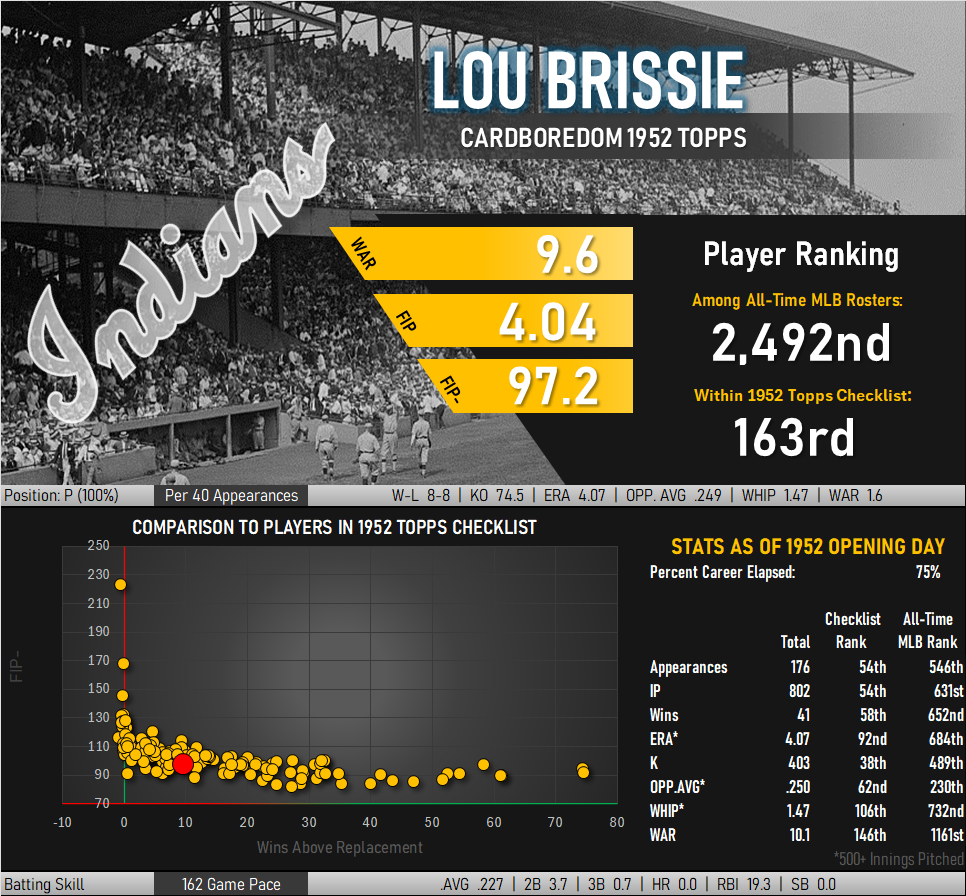

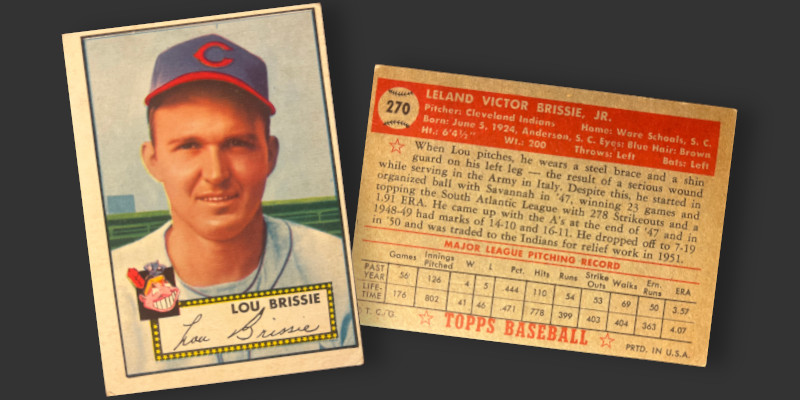

The obituary that appears for Lou Brissie on the MLB website is accompanied by an image of the former pitcher holding his 1952 Topps baseball card. It’s the perfect card to encapsulate his career. The text on the back gives you a very good overview of his exploits, starting with the fact that he pitched every game with his left leg fortified by steel armor.

The protection was necessary given Brissie’s proximity to an exploding German shell during a battle in 1944. The corporal’s unit suffered a casualty rate greater than 90 percent, with Brissie breaking both feet and taking shrapnel in his hands, thighs, and right shoulder. Most notably, his left leg was shredded and shattered, making his case a quick referral for amputation when he was brought out of the mud for triage.

Losing a leg wasn’t something that sat well with him. He was adamant that his leg not be amputated despite the likelihood of the wound becoming fatal if a runaway infection gained a foothold. Telling anyone that would listen that he was a ballplayer back home, he found a surgeon willing to piece him back together through 23 operations and start a regimen of the newly developed antibiotic penicillin. Through years of recovery and a willingness to tolerate recurrent infections and daily pain Brissie was eventually able to retake his spot on the pitching mound.

His claim of being a baseball player is an interesting one. To that point he had only played as a teenager in the textile leagues of South Carolina and had a single year of experience pitching for Presbyterian College. He had no contract with a Major League team or any minor league affiliate. Instead, he had a informal agreement with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia A’s that they would pay his tuition and bring him onboard once he had finished three years of play on a college team coached by former A’s infielder Chick Galloway.

To describe his recovery as successful would be quite the understatement. While Mack was trying to figure out the most gentle way to lower Brissie’s expectations, the pitcher with the leg brace won 23 games in his minor league arrival while almost lapping the league’s runners up in strikeouts and ERA. He made his MLB debut in the final game of the season with Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Tris Speaker, Lefty Grove, and Dizzy Dean all on hand. He followed that up with opening day pitching duties and 30 wins over the next two seasons alongside the task of facing more batters than any pitcher in the ’49 All-Star Game.

It was the stuff inspirational movies are made of, prompting Columbia pictures at one point to look into making a biopic of the A’s new star. The film studio asked for Brissie’s blessing to pursue the project but was rebuffed. Not everyone bothered to ask for permission: The Leaf Candy Company produced this card in 1949 and subsequently set in motion a chain of events that would shape the legal concept of a person’s right of publicity.

Bowman was the biggest producer of baseball cards in 1948 and was looking to repeat that distinction in the new year. Leaf issued its larger, more colorful cards one day ahead of Bowman and drew a legal complaint from its more established rival. Central to Bowman’s argument was the fact that Leaf did not have permission from the depicted players to use their images while Bowman had signed nearly 300 baseball players for this purpose. Leaf countered that baseball players were public figures whose permission was not needed, further noting that they had acquired the photos from a press photographer and could use them for any commercial purpose.

Bowman’s initial complaint was filed in Leaf’s home turf of Cook County and quickly bogged down in the legal process with each party taking opposite positions on who had the rights to a ballplayer’s image. Given the multistate nature of the baseball card business and early feedback from the Cook County proceedings, Bowman launched a secondary legal attack in its hometown of Philadelphia. With the early court seeming most sympathetic to the players’ (rather than Bowman’s) ownership exclusive publicity agreements, the company enlisted the assistance of each Philadelphia Athletics player depicted in the first series of the Leaf checklist.

As one of the four players, Brissie was named as a plaintiff in this second front against Leaf and argued that he had not given Leaf permission to make commercial use of his likeness. This suit expanded the list of defendants to include Leaf’s distributor network, where it stood the possibility of shrinking the competitor’s distribution footprint even if Bowman did not prevail in the full lawsuit. Cook County ultimately concluded that the players had control of commercial rights to their likeness but did not issue such a ruling until the following year. The judge overseeing the Philadelphia complaint quickly issued an injunction against Leaf selling its cards, effectively killing off the remainder of the 1949 set just days after Brissie added his name to the complaint. It would be decades (and an ownership change) before Leaf would again be able to mount a sustained entry into the baseball card market.

The stats above show that Brissie was a fairly decent batter for a pitcher. Despite having only one good leg, he beat out a triple off Joe Haynes and the Washington Senators in a 1949 game.

His ability to talk his way out of an amputation and into an antibiotic regimen matches up almost exactly with the experience of Morrie Martin, with whom Brissie played in 1951. Martin wasn’t the only pitching staff veteran with a close call — Brissie shared pitching duties in 1948 with bomber tail gunner Phil Marchildon who had been shot down and served out the remainder of the war in a POW camp. Bob Savage, another A’s hurler, had the distinction of earning three Purple Hearts, one more than Brissie.

All of this, from the near-death encounter through the subsequent athletic rebound makes for an inspirational tale. It’s no wonder that Leaf wanted to get his picture into as many packs of bubble gum as it could. Brissie’s story is also likely the reason why a race horse was given the name “Lou Brissie” in 2008 before going on to win races at Churchill Downs and Keeneland.