Has there ever been a better infield than the 1952 Brooklyn Dodgers? As far as I can tell, only the 1927 New York Giants rivaled the team in terms of quantity of infield Hall of Famers while an infamous gambling problem at 3B keeps the 1975 Cincinnati Reds at bay.

| Position | 1952 Dodgers | 1927 Giants | 1975 Reds |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | Roy Campanella (HOF) | Zack Taylor | Johnny Bench (HOF) |

| 1B | Gil Hodges (HOF) | Bill Terry (HOF) | Tony Perez (HOF) |

| 2B | Jackie Robinson (HOF) | Rogers Hornsby (HOF) | Joe Morgan (HOF) |

| SS | Pee Wee Reese (HOF) | Travis Jackson (HOF) | Dave Concepción |

| 3B | Billy Cox | Freddie Lindstrom (HOF) | Pete Rose (Idiot) |

| Name | Height | Weight (lbs.) |

|---|---|---|

| Roy Campanella | 5’8″ | 206 |

| Gil Hodges | 6’1.5″ | 200 |

| Jackie Robinson | 6’0″ | 205 |

| Pee Wee Reese | 5’9″ | 175 |

| Billy Cox | 5’8.5″ | 150 |

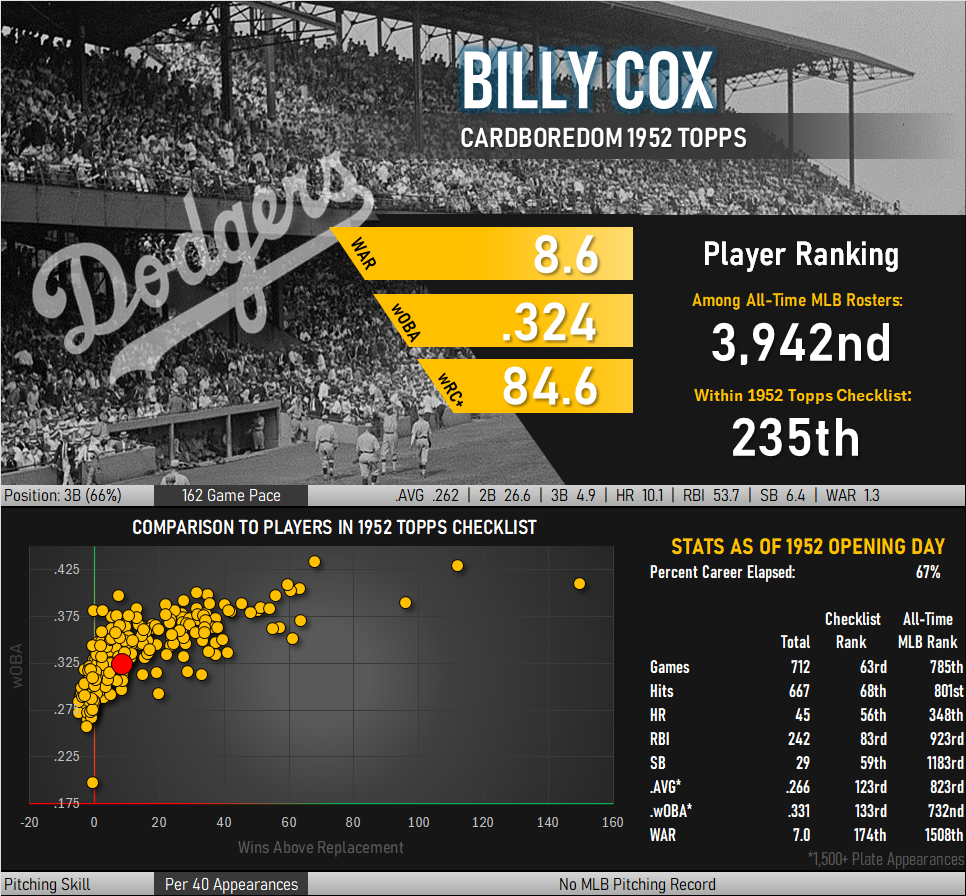

Billy Cox looked like the odd man out in the Dodgers lineup. He is tied (after a good meal) as the lightest ballplayer appearing in the ’52 Topps checklist and was reported to see the scale top out in the 130s fairly easily. Even at his heaviest weight, the rest of that infield had 25-56 lbs. on him and another 15 or so as the season dragged on. Brooklyn’s management was always looking to make roster improvements. That is, after all, how they arrived at having so many Hall of Famers in the infield to begin with. It was only natural that the front office would cast its eye towards Cox’s spot at third base as the next available slot for a newcomer.

He found himself battling for a role virtually every year with the team, a struggle that wore on him and was chronicled in Roger Kahn’s Boys of Summer. Often portrayed as a team that rallied itself into a cohesive group in the wake of racial integration, the Dodgers of this era were generally sitting atop an undercurrent of uncertain job prospects. It was one of the game’s more high stress clubhouses and a breeding ground for real and imagined fears to grow. Cox was one of seven children raised in a single parent household during the Great Depression and knew firsthand what job insecurity was like. Cox was always the poor kid trying to fit in.

The fact was the team’s deep farm system had provided too many talented players for the limited roster spots available. A series of championship near misses kept the tinkering going and those at the fringes of the starting roster lived in constant rotation in and out of the lineup. Cox, upon learning of yet another roster shift that threatened his playing time, once hurled his bags from a hotel window to the street 9 floors below.

Glove Man

What kept Cox in the lineup wasn’t his bat, but rather a very interesting glove. He was universally praised by contemporaries as being one of the finest defensive third basemen, a compliment that only gains in stature given that he had never played the position before joining the Dodgers. One of the most oft-quoted anecdotes about his fielding has Casey Stengel telling Brooks Robinson that the Orioles legend was the second greatest defensive force of all time, ranking behind the glove of Billy Cox.

He learned from the best. Cox was not always a Dodger, having come to the National League via the Pittsburgh Pirates. He played shortstop, making him an instant focus for the club’s most famous coach and former shortstop, Honus Wagner. If you’re going to get pointers on how to play ball, it helps to get them from one of the greatest players of all time.

I’m not going to shortchange Cox’s natural ability. He had fantastically quick hands and could get to any ball hit in his general area, position it just right, and fire it over to first with pinpoint accuracy. This contrasts with Wagner’s style in which he would grab a ball with preternaturally long arms and send it across the diamond in a single motion accompanied by a hail of debris.

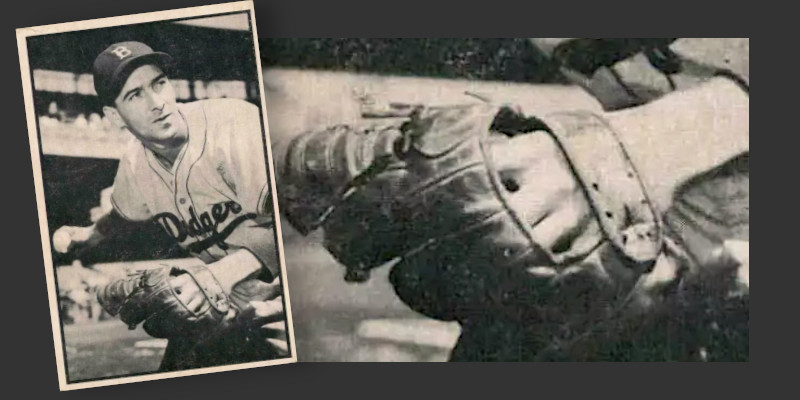

The student in this arrangement did all of this with a piece of equipment that would have been familiar to his septuagenarian teacher: A three finger glove. Glove design was progressing rapidly towards modern models in the 1940s and 50s with one of the most important features being lacing that tied together each of the fingers. The result of this change is a distribution of strength across the glove structure. Cox played with an older model and never upgraded.

The third and small fingers of a hand are weaker than the others and have trouble on their own handling hard hit baseballs. To combat this, ballplayers would double up these fingers into a single slot in the glove, effectively removing two weak fingers from play and replacing it with a single extra strong digit. Cox’s three finger glove did just that, though unlike many other players he chose to combine his third and middle fingers rather than double up on his pinkie. This can be clearly seen in his 1953 Bowman baseball card.

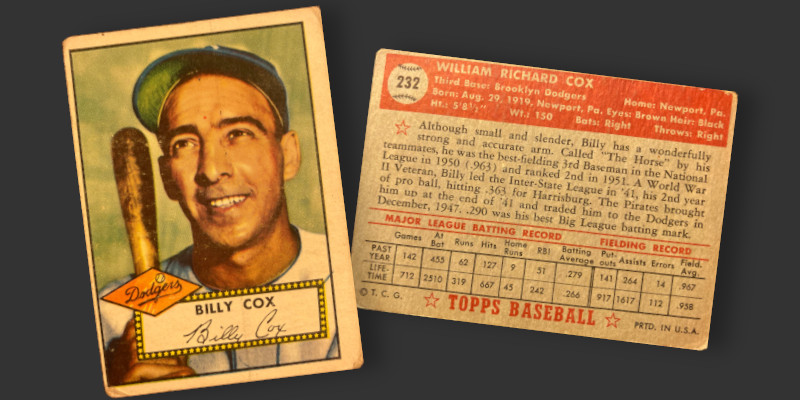

Billy Cox’s appearance in the ’52 Topps set comes with a photo focused on his bat rather his glove. The background is a bit different than other cards, with the coloring of the sky an almost sea-foam green rather than the partially cloudy but brightly lit offerings found with many his fellow Dodgers.

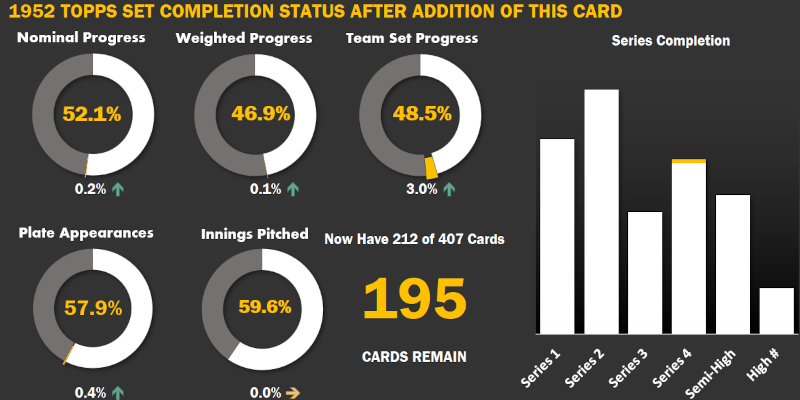

I added this example to my 1952 set as part of a multi-card lot rather than as a solo purchase. This is a bit unexpected, as cards of popular Brooklyn Dodgers figures rarely seem to get thrown into larger groupings of cards. They’re just too popular to be found in common bins, appearing instead at the cool kids’ table.