I am pretty sure Alex Cole, who is credited with 5 career home runs, might very well have produced a net negative number of longballs when all is said and done with the history of baseball. The origin of this home run black hole lies within Cole’s impressive speed. One could even say he moved so quickly that baseball card photographers could not keep up.

Neither of his two 1990 rookie cards picture him with his first MLB team. Drafted by the Cardinals in 1985, Cole was traded to the San Diego Padres in early 1990 before he could get into any games for St. Louis. Upper Deck included a Padres card of Cole in its late season High Series, though he appears to already be packing his equipment away for his next move, which had already taken place by the time Upper Deck got its card onto retailers’ shelves. Less than two years later he was on his way to join the Pittsburgh Pirates, getting photographed in a handful of games for Donruss before being picked up by the Colorado Rockies in the 1993 Expansion Draft. Eager to promote the new franchise in Denver, Donruss used those Pirates images on cards labeling him as part of either team.

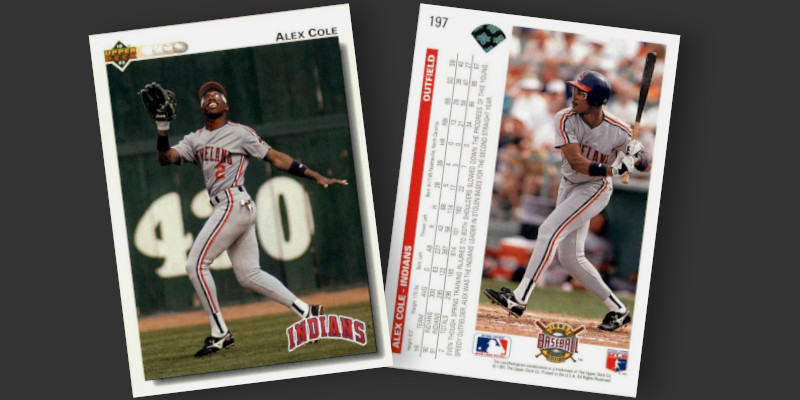

Cole commanded the attention of general managers once he arrived in the majors. Hitting .300 and stealing 40 bases in just 63 games (100+ SBs per 162 games) will do that. Just hitting .300 and swiping 40 bags per year will turn you into Lou Brock after 20 years. It wasn’t the Cardinals or Padres that got the benefit of putting him into the lineup, but rather a Cleveland Indians team with which he would have an unexpected impact. That is the organization he is depicted with in this example from 1992 Upper Deck.

Does anything stand out about the image used on the front? 420 feet is a very long distance for an outfield wall to be from home plate. That isn’t Cleveland Municipal Stadium in the background, but it may just as well have been.

As a team, the Cleveland Indians hit a combined 52 home runs at their home ballpark in 1990. That is not a terribly good number, as division rival Cecil Fielder hit 51 all by himself that season. Looking forward to 1991, the Indians took an inventory of their team’s strengths and concluded home runs were not on the list. What they did have an abundance of was speedy outfielders, led by Alex Cole.

How do you win a ballgame with nothing but speed? By taking away the other team’s strengths and reducing the game to nothing more than a footrace. Cleveland made the unusual decision to move the outfield fences away from home plate. Center field was pushed back 15 feet while the power alleys jumped nearly 25 feet from the plate. The 8′ fence was doubled to 16′ in one area, fortifying lower level seats against incoming fly balls and any armies invading via Lake Erie. Borderline home runs would now be long fly balls. The Indians weren’t hitting home runs anyway, so the reduction in scoring would come from opponents’ tallies. This resulted in a lot of extra outfield to cover, something a defense built around speed would excel at. Lumbering power hitters stood no chance against guys who would either catch fly balls or cut off shots rebounding off the wall. Fast Cleveland baserunners could leg out hits with opposing fielders struggling to keep up the pace in such a vast outfield. What could go wrong?

Quite a lot, actually. Cleveland finished in last place with a dismal 57-105 record. They were outscored 759-576 and finished 10 games behind the league’s second worst team. The Indians’ bats combined for a total of just 22 home runs at home.

This was, to put it mildly, a dumpster fire so severe that the team had no choice but to quickly course correct. Walls were lowered to 8′ around the entire outfield perimeter. Center field moved 11 feet closer to the plate and the alleys contracted by more than 30 feet. Home runs from the home team nearly tripled. Alex Cole was quietly exchanged for a pair of Pirates’ minor league prospects that never made it to the big leagues.

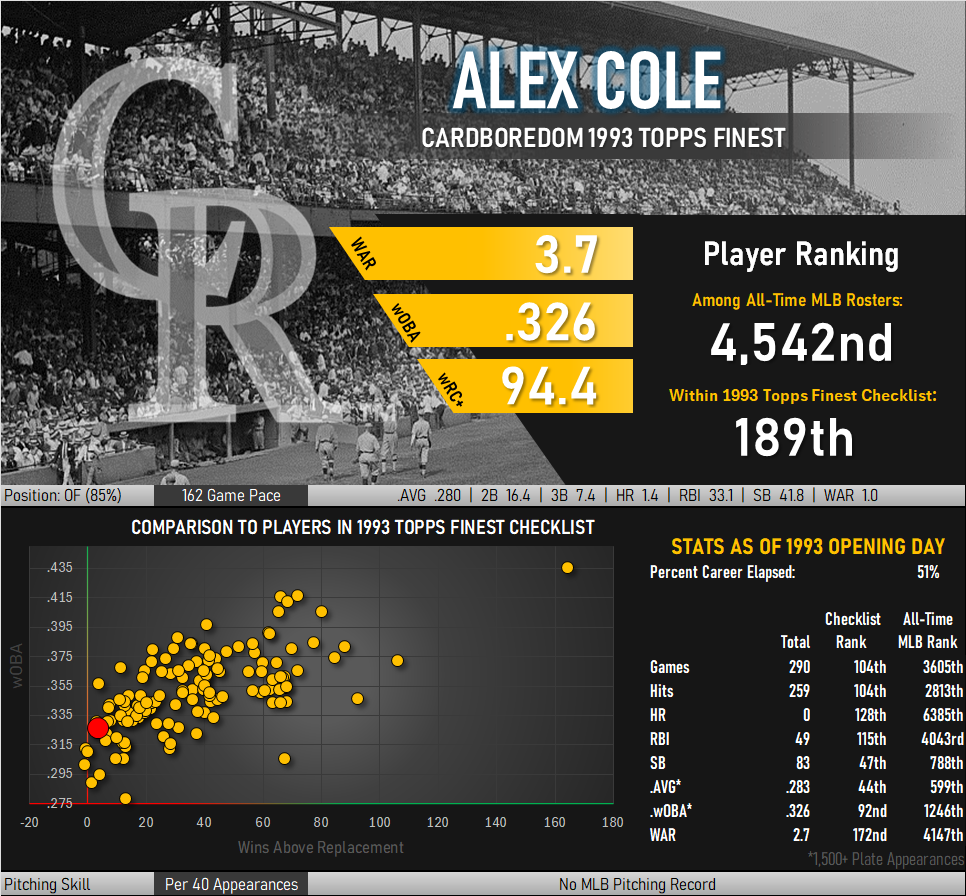

Cole played just 53 games for Pittsburgh before finding a home for two seasons with the expansion Colorado Rockies. Featuring baseball’s largest outfield area, Coors Field looked like just the sort of place where Cole’s defensive skill and speed would prove beneficial. This second attempt at the outrun everybody else playbook didn’t work out, so Cole was moved to the Minnesota Twins to help them chase down overly-bouncy hits on the Metrodome’s artificial turf. He belted 5 home runs for Minnesota, including an extra innings walk-off affair in 1994.

For all the talk of stolen bases, it was Cole’s outfield exploits that provided him with a positive career WAR. Combined with the number of home runs taken away by Cleveland’s Cole-inspired movement of the fences, he very well may be responsible for erasing more HRs from the MLB record books than he generated as a hitter.

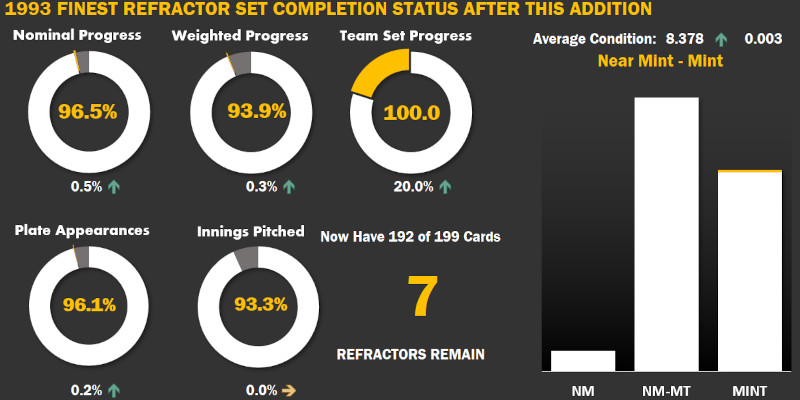

Alex Cole appears, correctly it should be noted, as a member of the Colorado Rockies in the ’93 Finest set. We don’t get to see a mix of home and away uniforms as we do on other cards between the front and back images. Instead, he switches between solid and striped pants. I guess the first ones got dirty sliding.

Aside from that, the key item to note about this card is that it has a long history as one of the tougher ones to come across. Over the last three years a copy has shown up about every 3-4 months versus the near monthly average for most names in the set. Such a limited number of observed transactions has been the case for much of the past two decades. When I added one to my set I was getting fairly close to completion and had reached a mindset in which I did not care if I was getting a good deal on the card or not. I just wanted to complete it. It took forever to catch up with this speedy ballplayer.