Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up was introduced by J.M. Barrie to the world in 1904. The story was built upon over the next 50 years by a subsequent Broadway musical, novel, silent film, and a full-fledged Disney production. The familiar story grew further in the early ’90s with the addition of baseball to the roster of Neverland’s activities. The tale of a boy who remained forever young has stayed with more than a century of audiences, and for a portion of that time his shadow could be seen playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

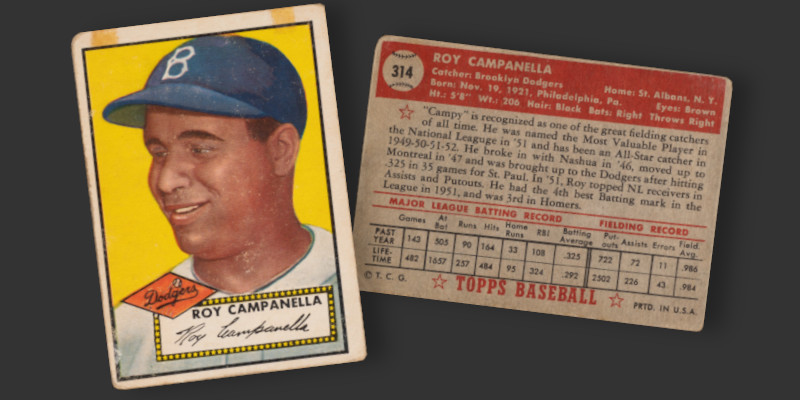

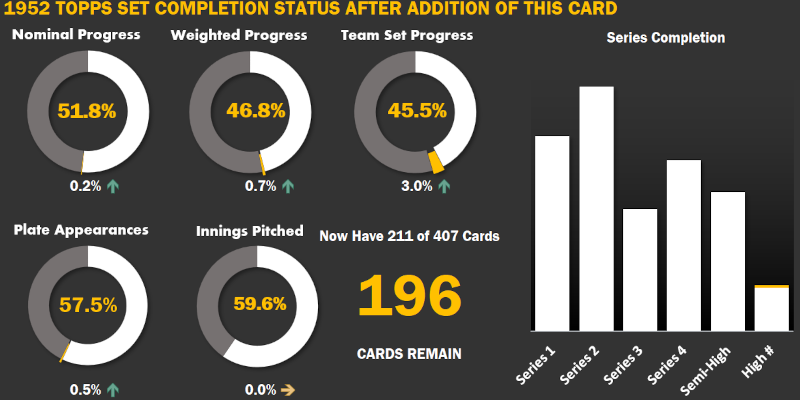

Two weeks ago I teased that a major addition had been made to my in-progress 1952 set building project. Arriving at the same time as my Bob Cain high number was this Roy Campanella card. It’s fantastic, with incredibly bright yellow, blue, and orange ink. Offsetting this are rounded corners, diamond-cut centering, a bit of surface wear, and evidence of stamp hinges along the top border. In other words, stuff that doesn’t matter because its Campy-freaking-Campanella.

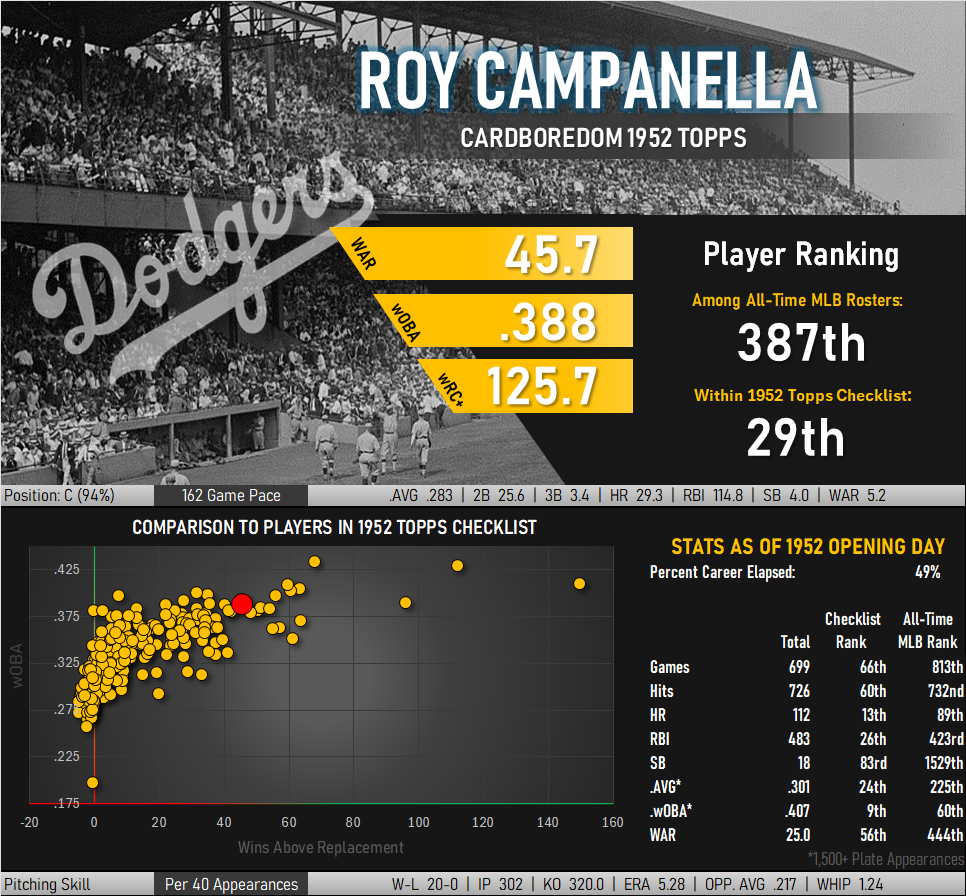

Based on the Beckett price guides I grew up reading, this would be Campy’s fourth year card and something I would consider to be an early card of the Dodger backstop. One could be forgiven for thinking him to be only recently removed from sandlot ball in his hometown of Philadelphia. Topps’ biographical text on the back nods a bit in the direction of a longer history, highlighting how Campanella “broke” into baseball in 1946. That still understates the veteran presence anchoring a series of Dodgers teams that took another 70 years to rival.

Campanella was already playing with the Washington Elite Giants by 1937 and by 1939 was batting .352 against Josh Gibson while playing in Yankee Stadium in the Negro National League World Series. If you include the current 1952 season, Campy’s career to date had already outlasted the entire length of Joe DiMaggio’s career, including Joe D.’s time in the military. He was barely five years away from being a grandfather when this card was released.

What the card gets right is its focus on Campanella’s defense, calling him “one of the great fielding catchers of all time.” He remains the all-time leader in throwing out runners attempting to steal bases, finishing with a career mark of 57.4% and a string of seasons in which he routinely knocked out close to 70% of baserunners. For comparison purposes it is worth nothing that Salvador Perez is the current MLB leader with 33.2% of runners thrown out. Campanella’s career average has only been matched on a single-season basis on four occasions this century and none since 2005. The feat is even more impressive when you consider how often Campanella played with a broken hand.

Campy was durable, often catching every game for multi-month periods and not dropping below 100 games in a season in the last 9 seasons of his career. This was in addition to a lengthy history of extensive barnstorming commitments and routine full-time play in warm weather winter leagues. That durability included an ability to counteract speeding runners attempting to dislodge a ball thrown to home plate. Some of those collisions resulted in him playing through injuries, but just as often he would manage to hit the runner just as hard and discourage further attempts. Just take a look at the airborne aftermath of his run-ins with the Yankees’ Billy Martin.

Paraphrasing Yogi Berra, half of catching is physical with the other 90% is mental. Campanella, who never finished high school, was never questioned about his mental acuity on the field. He proved masterful at calming young pitchers, elevating the game of ones past their prime, and calling just the right pitches. Once established behind the plate it was rare to find a pitcher shaking off one of the signs he would flash through high visibility taped fingers. Campy memorably shouted at Rex Barney after the pitcher shook him off and immediately blew a no-hitter, yelling “I’m smarter than you and will always be smarter than you!” He told an inexperienced Don Newcombe that “not only are you wrong, you’re loud wrong” on the mound. I don’t recall him ever losing one of these arguments with a pitcher.

Catching Neverland

Like Berra, Campanella had a ready supply of commentary that impart 90% laughter and the other half some deeper truth. He once said (in his trademark high-pitched boyish voice), “To play this game good, a lot of you has to be a little boy.” Campy epitomized this every chance he got, seemingly living up to the “never grow up” ethos of Peter Pan.

He extensively pursued other childhood interests. An elaborate model railroad with more than 50 locomotives filled one section of an expansive home in Glen Cove. An entire room with custom cabinetry housed tank after tank of tropical fish and elaborate underwater decorations, effectively giving him a real life lagoon to match the one in the Neverland of Barrie’s creation.

Pan, of course, is very mischievous but generally considered a good guy in the course of the play. He and the lost boys have no problem exhibiting the “bad form” denounced by Captain Hook as they explore the offerings of Neverland. Similarly, Campanella had no problems playing a little dirty if the opposing team was a bit dirtier. His Elite Giants would frustrate opposing pitchers who favored using the spitball by giving game balls a pregame rub with mustard powder. The offending pitcher would touch the ball, reach for some saliva, and found themselves tormented for the next two hours of pitching in the sun. Campy’s own experience catching spitballers (and protecting them from umpires) likely contributed to his success in catching Preacher Roe’s 22-3 season.

Running Out of Pixie Dust

You could almost call Campanella’s decade-long Brooklyn run magical. Magic, like ballplayers, has its limits. The magic of Neverland was fueled by fairy dust that kept its inhabitants forever young and granted powers of flight and superhuman recuperation. Campanella was one of the youngest players to have ever played the game and was not yet 18 when he played in the ’39 NNL World Series. He kept this youth about him even as his hands aged, broken repeatedly by pitches received as both a catcher and a batter.

Campanella’s final season, 1957, saw the Dodgers ownership group announce its intention to relocate the team to Los Angeles, effectively leaving the Neverland of Brooklyn. Like the Dodgers, the magic was leaving. Jackie Robinson had been unceremoniously traded to the New York Giants the previous off-season and elected to retire. Campanella’s injuries were proving cumulative in nature, resulting in fingers that could not close around a ball and leaving him to resort to trapping pitches in the dirt. Previously immune to the running game, the Dodgers found themselves with opponents who realized Campanella’s arm could no longer gun them down. The team found itself uncompetitive for the first time since his arrival.

People familiar with the name Campanella know about the car crash that paralyzed Campy prior to the 1958 season. Campanella’s career was over.

For all the talk of “what-if” Campanella had been able to play as a Los Angeles Dodger, it was pretty clear that his days as an effective player were gone. He was a 36-year-old catcher who could no longer grip a ball or effectively swing a bat. At best fans could have expected one more year of wishing he could be young just once more while he took up pinch hitting duties and embarked on a crash course of teaching the Lost Boys of LA how to catch.

Clap if You Believe

Campanella’s career was winding down, but the way in which it ended was a real shock. Forever young ballplayers aren’t supposed to get hurt. They’re supposed to get up. Campanella had always gotten up before, brushing off beanballs, spikes, and kamikaze baserunners heading for the plate.

Good guys aren’t supposed to die in a children’s story. Tinkerbell, perhaps the most endearing character in all of Pan’s universe, moves to sacrifice her life in order to save Peter from being poisoned by Captain Hook. Children’s gasps and the worried silence that accompanies this scene lead up to the most memorable part of the story: The part where the audience becomes part of the tale itself. That moment was still to come in Roy’s story.

Campanella slowly stabilized as those following his story processed events. Now a quadriplegic, he would spend months immobile in a purpose-built hospital bedframe before undergoing rigorous physical therapy. Ever the Dodgers cheerleader, he followed accounts of their season from his frame and eventually a wheelchair. At season end he was invited to attend Game 3 of the World Series.

He entered Yankee Stadium unobtrusively, without an announcement and was carried to his seat after more than an inning of place had paced. Those around him noticed his arrival and began to shout encouragement and clap their hands. A spontaneous ovation began to sweep one of the largest sports arenas ever built, building momentum as word of his arrival spread. The game, still active, ground to a halt as the players themselves rushed to take part in saluting the guy who had played so well against them.

Tinkerbell grabbed audiences’ hearts when she saved Peter. The script calls for her revival, though it can only take place through a sustained clapping and verbal encouragement from the audience that builds until magic can once again take over. Capanella would generate that reaction for the rest of his life.

Pitchers don’t know a Goddamn thing. They’s why they have catchers.

-Roy Campanella, September 19, 1949