Baseball players will generally do anything to stay on the field, often playing through injuries. Ballplayers have tried to stay in the game through fractures, concussions, and burns as well as “intestinal discomfort.” I’m sure there has even been a fair share of toothaches in that all-time injury roster.

Max Scherzer, already on the injured reserve, suffered a minor additional setback in 2022 when he was bitten by a dog. Former Dodger Alex Guerrero had a portion of his ear bitten off two years earlier in a fight by teammate Miguel Olivo.

Perhaps the oddest injury inflicted via dental means took place in a 1933 Knoxville Smokies game when the pitcher bit his own rear end. He did this not through impressive flexibility, but rather via a set of false teeth that had become necessary due to the effects of heavy tobacco use. Clarence Blethen tried to bunt his way onto first base but was forced to dive by an off-kilter throw and attempted tag. The ensuing twist and lunge shifted the false teeth that he had stored for safekeeping in his back pocket, taking a bite out of his flank. He remained in the game.

Blethen was at one time a major league player, though only marginally so. He pitched in 5 games for the 1923 Boston Red Sox and got into an additional 2 innings for Brooklyn in 1929. He does not appear to have been depicted on a baseball card until the 1987 release of a novelty boxed set from Star celebrating famous baseball bloopers.

Speaking of Bloopers…How ‘Bout Those A’s?

The Athletics were playing Moneyball long before the famed 2001 season. They just didn’t know how to do it.

Almost immediately after their formation, Connie Mack and the A’s tried to outspend their National League competition. The resulting “$100,000 Infield” led to quick success but also precipitated the team’s first brush with fiscal calamity. Mack quickly dumped payroll following the club’s 1914 championship and embarked on a series of feast and famine ups and downs that saw the team tie by 1930 with the Red Sox for most championships in baseball history. Those A’s racked up more championships than all other Philadelphia teams of the past century and a half (baseball and otherwise).

By the advent of the 1950s it was becoming apparent that even maintaining a low payroll wouldn’t keep the team alive. Expense reduction had already blunted the team’s competitiveness and could not provide much more benefit to the bottom line. Shibe Park was unable to accommodate fans who wished to drive to the game, was heavily mortgaged, and bleeding even too much cash for the park’s infamous “Spite Fence” to staunch. On top of this, the octogenarian Mack was being eased out in favor of his sons who had their own internal squabbles.

There were 77 home games to be played in any given season and the team could ill afford to miss the gate receipts from a single contest. What kind of pitchers do you seek in that kind of environment? You look for pitchers with exceptional stamina. Why pay for a starter and a reliever when you can get by on a complete game and a single paycheck? Mr. Mack wasn’t paying the staff to take the day off after throwing a measly five or six innings.

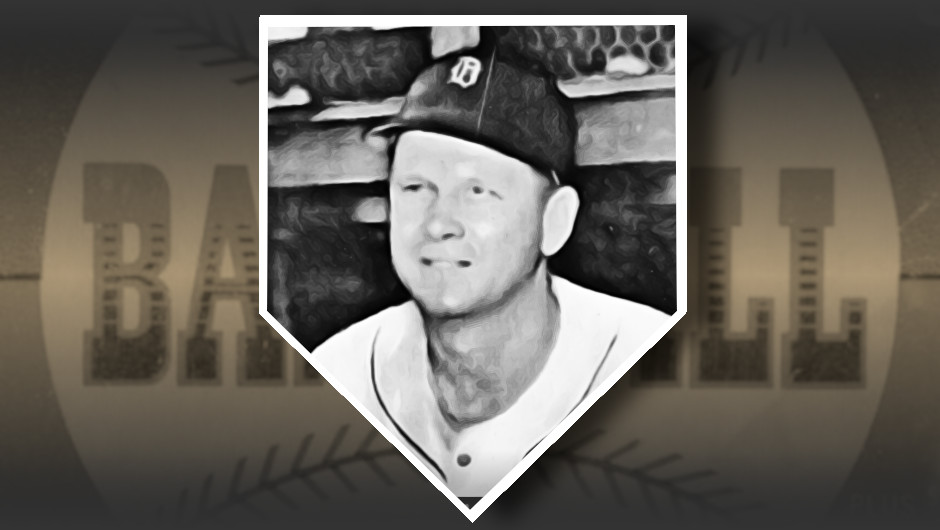

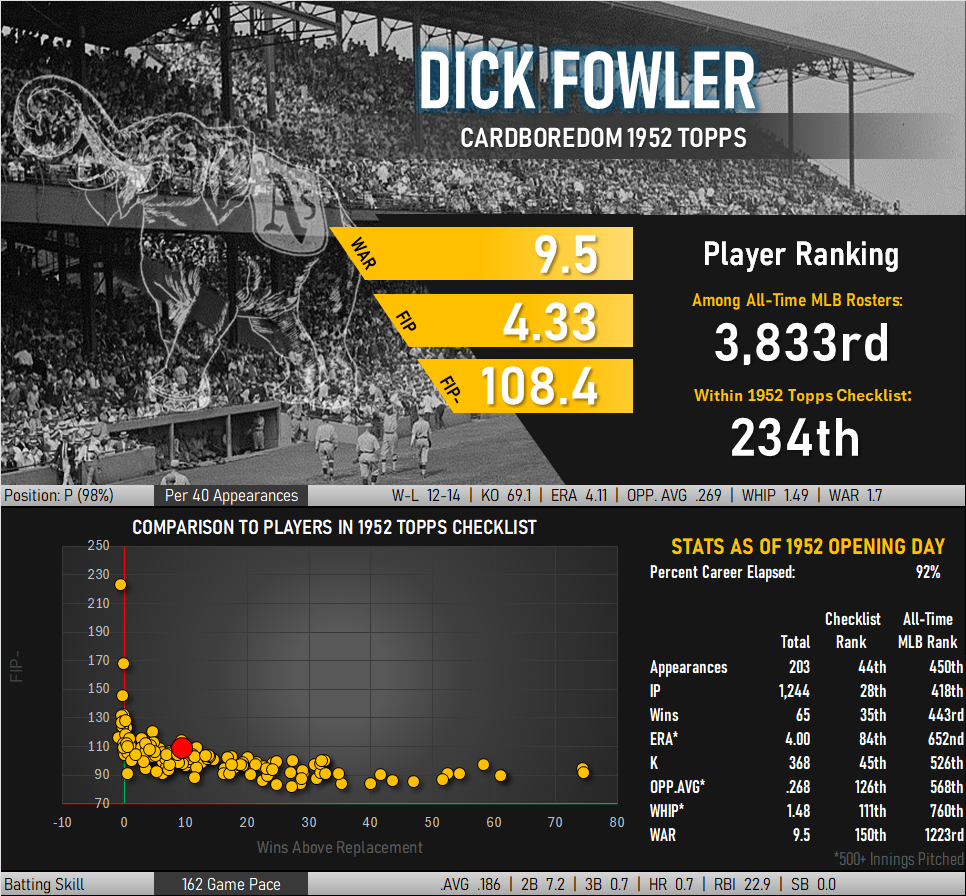

The starting five of Philadelphia’s rotation reflected the view of the front office. Over the course of their careers they collectively posted complete games in 43% of all their starts. One of the workhorse arms of this group belonged to Dick Fowler. The Canadian hurler earned his spot on the mound, consistently giving 200+ innings annually and posting three consecutive winning seasons with double digit wins.

Shoulder trouble hit hard in 1950, threatening his spot with the team. Fowler tried to pitch through the pain but saw his effectiveness nosedive. Still, he took every opportunity to take the mound and stayed as long as possible. The shoulder pain continued to build, eventually radiating up his neck and into his jaw. Seeking relief, he had his lower teeth removed in hopes of extending a career that unfolded in its entirety in an Athletics uniform.

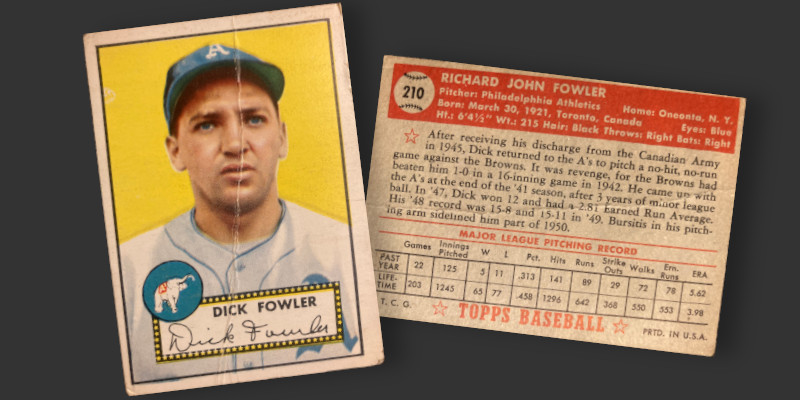

The statistical table on the back of Fowler’s 1952 Topps baseball card shows him having pitched in 203 of the 221 games in which he would appear. This turned out to be his final season and the biographical text ends with a note about an injury having already sidelined him for a partial season.

Of more interest is the way the bio starts out: Telling readers about Fowler’s military service in Canada. He is one of three Canadian born players in the set checklist, but had become a US citizen during the intervening years since the war.

The Dick Fowler card I added to my 1952 Topps set building project was the last card in a group of three purchased from the same seller. The card is in much lower grade than the other two, but shipping was already taken care by the other two buys and the price to tack on this card was right. Connie Mack would be proud.