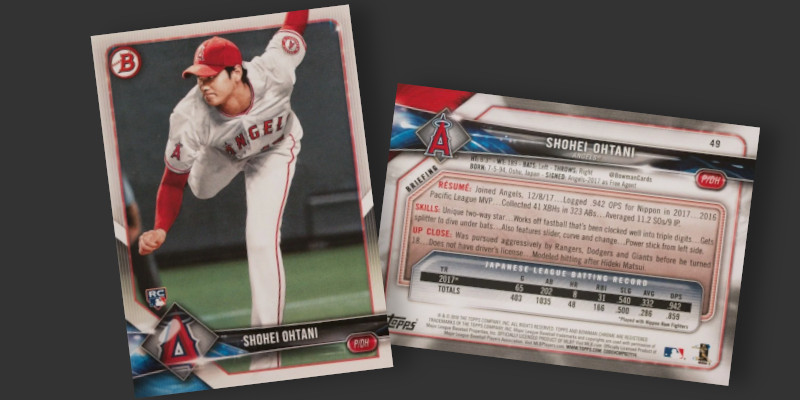

Shohei Ohtani is special. Just last week he wrapped up baseball’s first 50/50 season despite being an injured pitcher rehabbing from his second Tommy John surgery. Right at the All-Star Break I picked up this rookie card, which now constitutes the most modern bit of cardboard in my collection.

He’s been a dual threat since day one, but this generally referred to his ability to hit and pitch. With a career high of 24 bags prior to 2024, stealing bases was a decent but secondary part of his game. Still, like anything he does, he managed to sometimes swipe a base in the most exciting way. Ohtani was intentionally walked in a 2021 contest, ran to third on a single, and then stole home for what would prove to be the winning run of the ballgame.

Pitchers who steal home are an exceedingly rare bunch. Ohtani’s stolen base came in a game in which he played the role of DH. The Dodgers’ Darren Dreifort accomplished the feat in a game 20 years earlier in which he was pitching, making him the last pitcher prior to Ohtani to steal home. Dreifort’s deed took place in the National League where pitchers regularly took their place in the batter’s box and on the basepaths until the present decade. To find the junior circuit’s predecessor to Ohtani, one must look back to 1950.

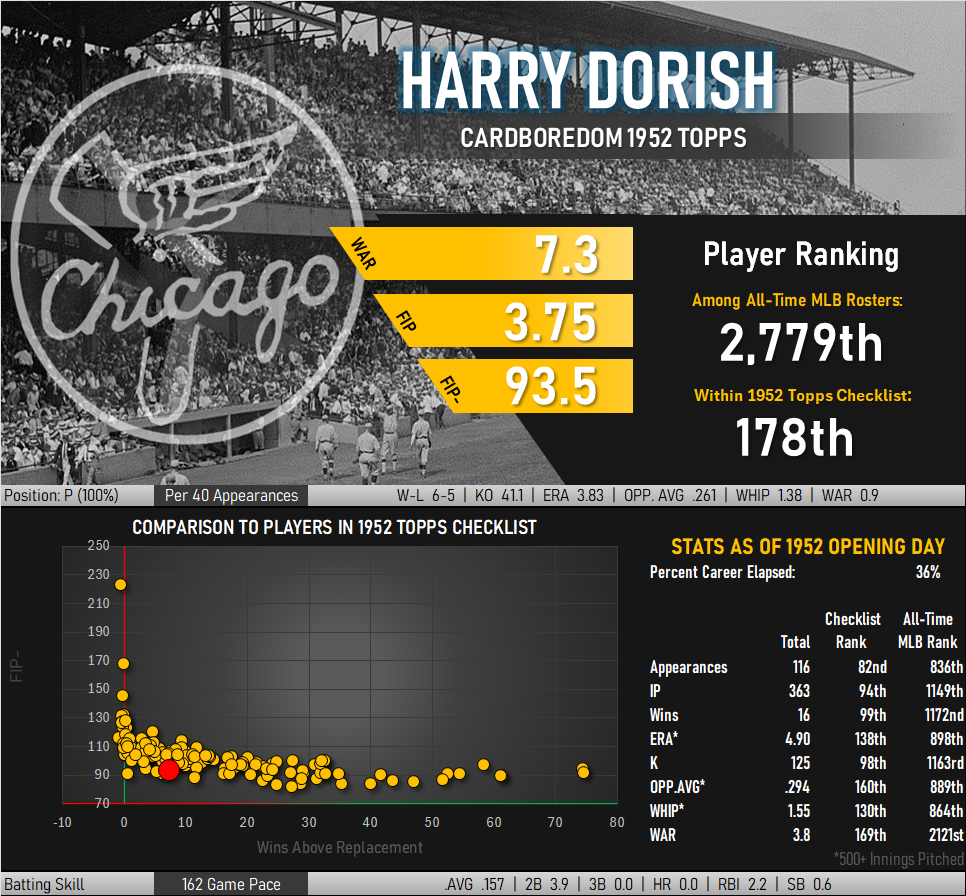

In the second game of a June 2 double header between the St. Louis Browns and Washington Senators, pitcher Fritz Dorish knocked in two fifth-inning runs with a double. He took third base on a wild pitch, and then stole home as part of a double steal one batter later. The most interesting part of this was the fact that Dorish only attempted to steal one base in his entire 10 year career. He is a perfect 1 for 1 and only took off running when the ultimate prize was available.

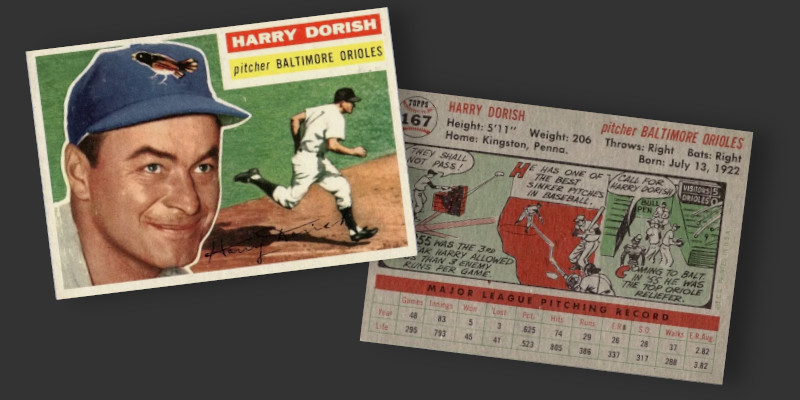

This play was likely on the mind of Topps’ staff when they laid out the design for his 1956 card. The action shot depicts Dorish not as a pitcher, but as a runner. The photo is not his specific dash to the plate as he wore #46 in that game, but it still captures one of the best highlights of his career.

The sinkerball specialist was credited with the victory and logged a complete game in the contest, single-handedly driving in or scoring enough runs to equal the opponents’ output. It was the best outing of his season and a departure from several years of middling performance alternating between starting and relief roles. He recorded a 6.44 ERA in 1950 and had a 4.90 mark on the back of his 1952 baseball cards. This was remedied by shifting his focus almost entirely to the bullpen, lowering his career ERA by more than full run over the next few years.

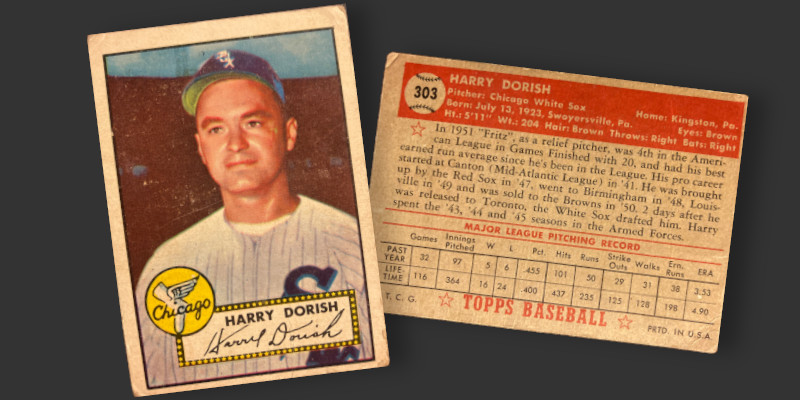

Fritz Dorish in 1952 Topps

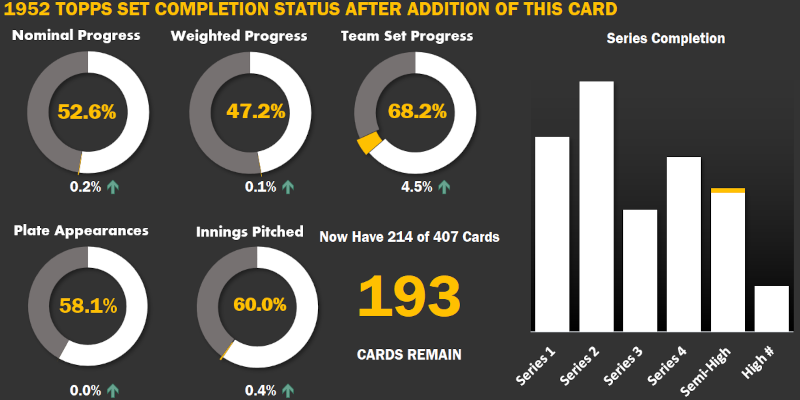

Adding this card to my set takes me past the ⅔ team set completion mark. I probably have more White Sox players than any other team at this point as chasing them down presents little difficulty. Many of the team’s better players, such as Billy Pierce and Eddie Robinson, are often lumped in with common cards. There are zero winged socks among the scarce high numbered series. Only the relatively plentiful Minnie Minoso rookie represents any sort of financial challenge.

As one of the 7 semi-high number White Sox cards, the Dorish card counts among the team’s cards with fewer available copies. Like the Luis Aloma card appearing just a few digits further into the checklist, this card exhibits an intriguing lighting situation against a darkening blue sky. It features a different birth year than what is reported on Dorish’s 1956 Topps card.