Ken Caminiti might be the baseball player who had the greatest impact in the last 50 years, and his contribution did not even come until a year after he last played the game. That is when Sports Illustrated reporter Tom Verducci sat down with Caminiti to discuss the use of performance enhancing drugs that had seemingly permeated the sport.

Caminiti wasn’t the biggest name in baseball, though he did beat out guys like Mike Piazza and Barry Bonds for the 1996 NL MVP Award. He had well-known struggles with alcohol and several hard drugs and could be counted on by reporters to speak candidly about these subjects. His retirement at the end of the 2001 season coupled with his willingness to talk provided the material to write what would become a defining piece of sports writing.

In the story, Caminiti admits having used PEDs and attributes his MVP award to their effects. He hit a nerve when he said, “I’ve made a ton of mistakes. I don’ think using steroids is one of them.” He went on to discuss how he had been personally affected and ventured that at least half of MLB players were active users. Simply put, fans were given a glimpse from a believable participant that showed no remorse for what was happening.

Caminiti’s interview came with a precedent. SI generated a firestorm of controversy with the magazine’s July 4, 1955 interview with Preacher Roe. Like Caminiti, Roe was only one year into retirement when he sat down with writer Dick Young to discuss his career. The conversation quickly moved to a discussion of Roe’s regular use of the spitball and other illegal methods of doctoring baseballs. Fans were outraged, generating a steady stream of letters to the editor decrying not only Roe’s cheating but the fact that a media outlet would publicize this information.

The Caminiti SI article was published in late May 2002. Like with its predecessor 47 years earlier, reaction was swift. Large swathes of baseball insiders derided Caminiti’s willingness to talk (Dusty Baker, 2022’s championship manager, is quoted as calling him a snitch). Several well-known teammates played down Caminiti’s claims, saying people don’t know the truth unless they are present in the clubhouse (leaving out the fact that Caminiti himself is our first witness into that very clubhouse). The admission and claim that half of MLB rosters could be playing dirty shook fans’ confidence seemingly more than the contents of Mark McGwire’s locker or Barry Bonds’ superhuman homerun totals.

One reader of the report was Arizona Senator John McCain. An ardent baseball fan and well connected in the machinery of Capitol Hill, McCain responded to the report by instigating a subcommittee hearing on the use of PEDs in baseball. The full text of the hearing is available and directly credits the Caminiti article as leading to its formation. Baseball’s steroid problem suddenly had both political attention and growing public momentum. Siezing on the newfound public interest in the topic, Jose Canseco launched into the writing of a tell-all book.

Caminiti, meanwhile, continued to fight his own personal battles. In addition to permanently needing external testosterone treatments after years of steroid use, he struggled with a recurring drug habit. He died of an overdose at the age of 41 in 2004. Some elements of myth crept into his story at this point, with more than one acquaintance of mine remembering his early death as being caused by steroids rather than the other substances that actually tripped him up. Still, this event only made calls for action grow louder.

Baseball’s 2002 hearings did not go over well for the sport, and Caminiti’s death only enhanced his effect on public perception. Canseco’s book launched in January 2005 alongside a wide-ranging media tour that only fanned the flames. Political actors moved beyond sleepy subcommittee hearings, eventually bringing in the game’s biggest names in front of Congress. Mark McGwire famously said he wasn’t there to talk about the past, Sammy Sosa suddenly didn’t speak English well enough to answer questions, and Rafael Palmeiro memorably pointed his finger at representatives. A pair of San Francisco Chronicle reporters wrote Game of Shadows, an investigative series of articles and a 2006 book that connected Barry Bonds and other major stars to PEDs supplied by BALCO.

These developments in turn led baseball to finally do something serious. The Commissioner’s Office requested an investigation into PED use in the sport and selected George Mitchell to spearhead the effort. Mitchell’s investigation culminated 20 months later with the publication of his findings as “The Mitchell Report.” While finding very little player cooperation and only following a few specific threads of inquiry, the report became the defining document of the Steroid Era. Despite its limitations, the report cast doubt on the track record of 89 players.

Since the report’s publication, the sport has undergone significant changes to its labor agreement and testing policies. PED use undoubtedly remains an intractable problem, though regular testing has helped reduce their prevalence to some degree. Fans seem more at ease with the current competitive environment that they did two decades ago. Ken Caminiti played an integral part in getting the ball rolling towards this outcome. Had he not agreed to talk with Tom Verducci all those years ago, things may have ended up much differently for the game. He may have changed baseball more than anyone else in recent memory.

Caminiti was a switch hitter, an ability that helped him keep from being jammed by opposing pitchers. In September 1995 he connected from both sides of the plate against the Cubs for a pair of homeruns. He repeated the feat the next day with another pair of homers from opposite sides of the plate. Two days later he did this for a third time, becoming the first player to switch hit homeruns in such a span. For me that is the high of Caminiti’s career.

Steroid Era Cardboard

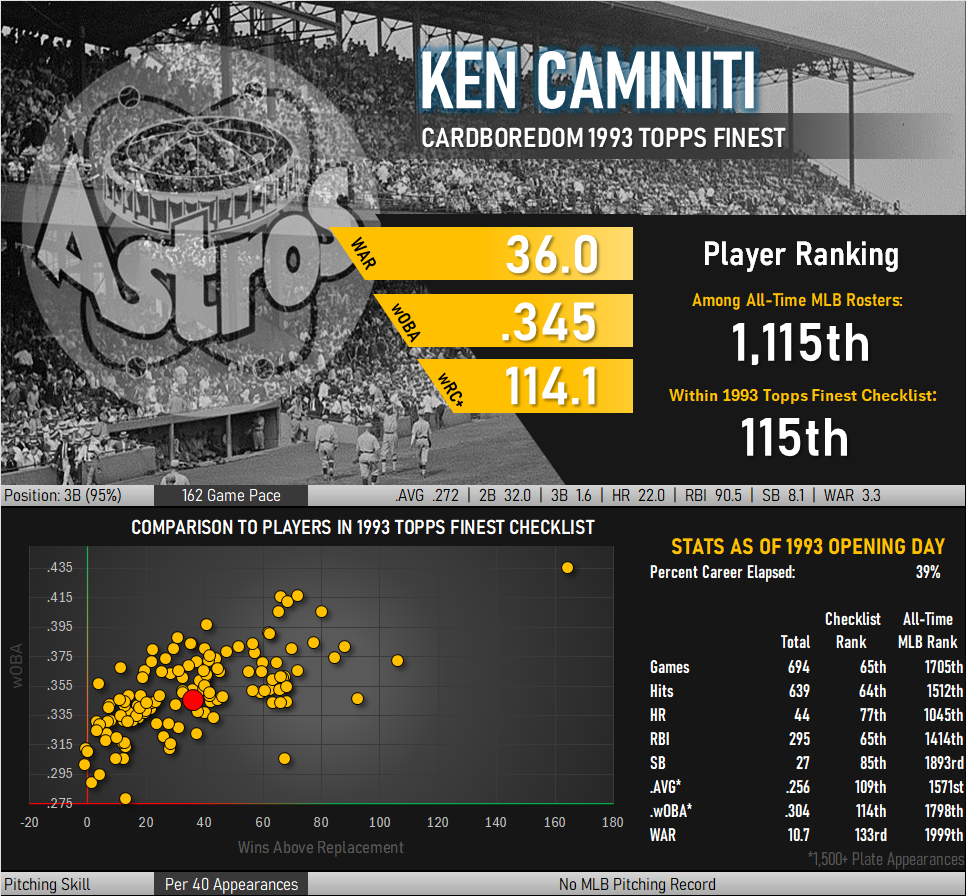

At its heart, the 1993 Finest set is one that captures baseball’s Steroid Era. It is therefore fitting that Caminiti joins the checklist, despite having not hit more than 13 homeruns in a season prior to this point. He still hustled, likely influencing the choice of a running photo on the front of card #131. Somewhat intense at times, he looks on the back of the card as if he is seeing someone in the distance raiding his ever-present supply of Snickers bars.

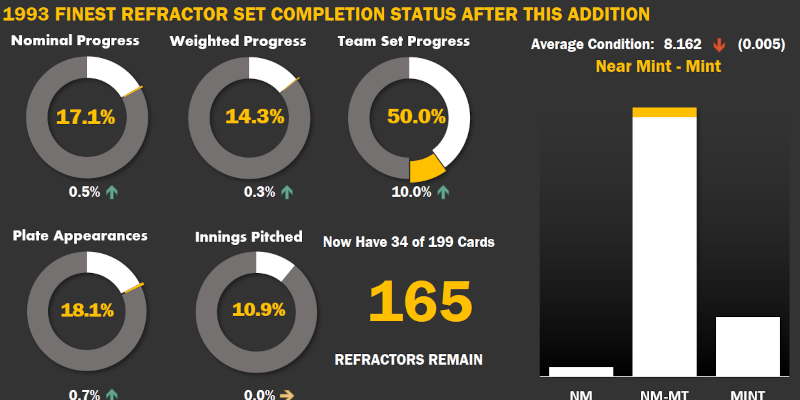

This particular card joined my collection from yet another eBay auction, coming from the same seller that supplied the Dave Hollins card.