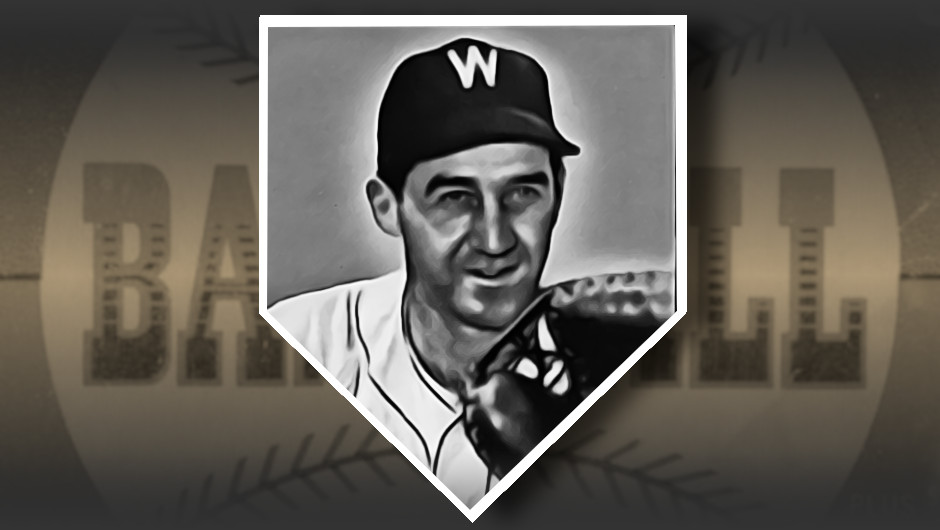

Playing primarily for the Washington Senators, the only way Mickey Grasso was ever going to see the inside of a World Series ballpark would be to buy a ticket. There was a time, however, when this light-hitting backstop competed for a much more global World Series title 4,200 miles away from Washington’s Griffith Stadium.

Grasso joined the Army in January 1942, just a month after the US entered the war. His 34th Infantry Division was the first to be deployed to the European Theater and Grasso found himself fighting in North Africa. Just over a year into his deployment he was captured by retreating German forces and moved by plane to a prison camp deep inside Germany. He would spend the next 27 months there.

The Baseball League

Grasso was counted among more than 2,900 Americans held at Stalag III-B, located near Furstenberg. Like many POWs of the time, he had access to regular care packages from the Red Cross and YMCA. The latter provided recreational equipment for prisoners throughout the war and provided Grasso’s camp with a cache of baseball paraphernalia. It didn’t take long for pickup games of baseball to begin morphing into organized teams and, finally, American and National League playing divisions. Naming teams proved a popular activity, and Grasso found a role as a member of the Zoot-Suiters. Grasso was one of several participants with professional experience, making him highly sought after. By August 1944 the newly established AL and NL champs faced off against each other in a makeshift World Series.

The champs didn’t mind not having the opportunity to defend their title the following year. In late January the Russian front was fast approaching from the east. The camp was evacuated ahead of their arrival with the goal of regrouping the prisoners further inside German lines. Prisoners marched on foot for a week to their next destination. Grasso, seven Americans, a Frenchman, and a Jewish German boy slipped away during a break for rest. They traveled on foot to the southwest, passing themselves off as a prison work detail being led by the German speaking boy. Through this method they evaded several close calls. They eventually “borrowed” a rowboat from an obliging house along the Elbe River and crossed over to the eastern bank which was controlled by the Americans. Grasso was safe and going home.

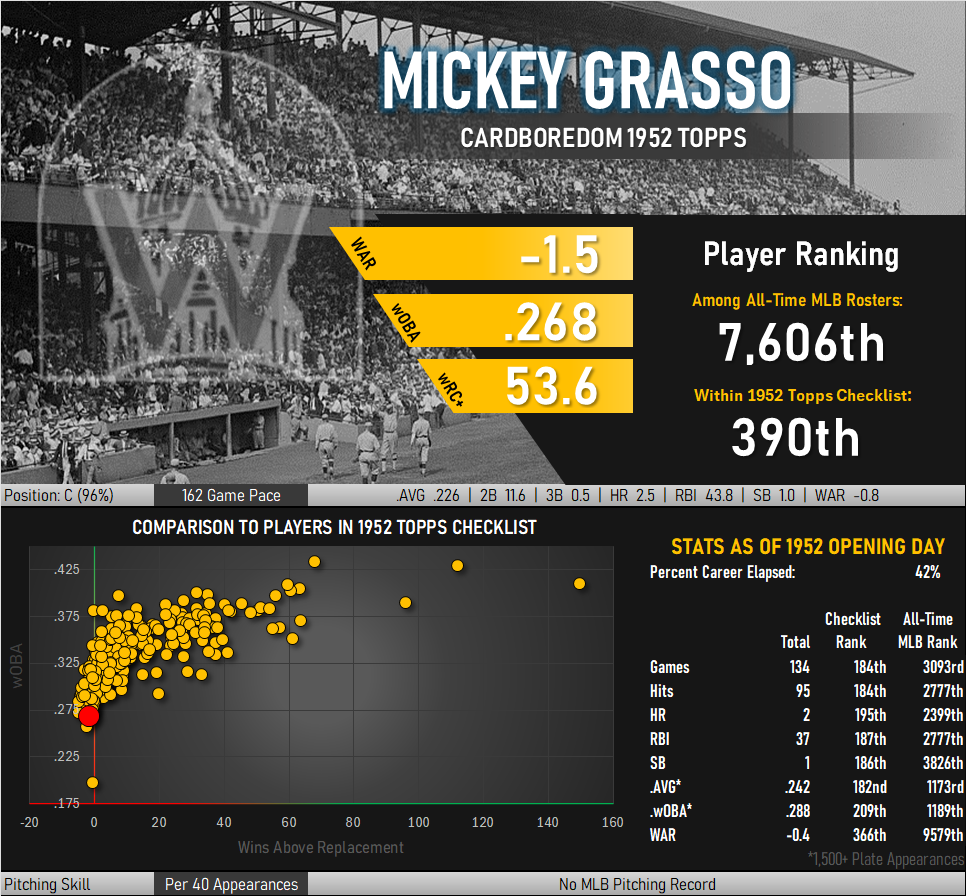

Grasso was not a good ballplayer by MLB standards. He largely played backup roles, getting into just over 300 games from 1946-1955. He did, however, draw 81 walks giving him over a mile of walking to first base over this span.

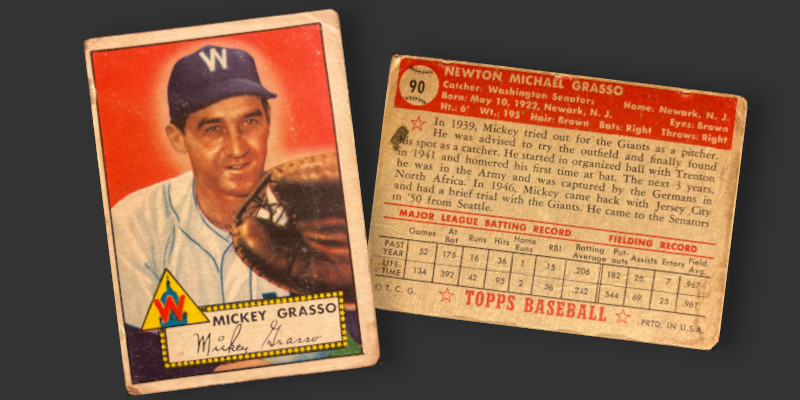

My 1952 Topps Mickey Card

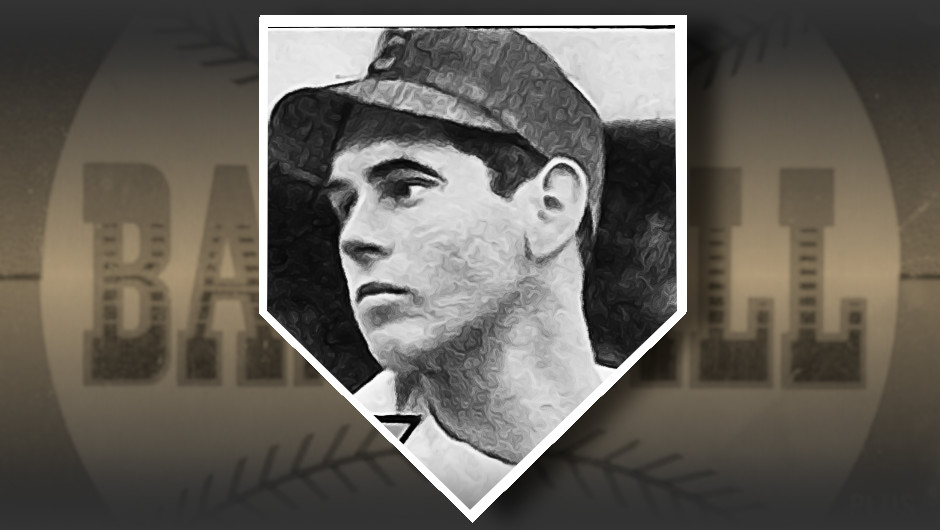

There are four cards in the ’52 Topps set featuring a guy named “Mickey.” Two of these represent players named after Mickey Cochrane, the greatest catcher in baseball history by the early Depression years. Mickey Mantle’s father gave him the name in hopes of imbuing his son with athletic greatness. Mickey Grasso was already 5 years old when Cochrane took his first big league swing. His name was changed to Mickey by teammates who swore his face was an exact duplicate of the famous backstop.

Judging from the 1936 Goudey card above, Grasso really did look a lot like Cochrane. The similarities don’t stop with their face and defensive position, either. Both were given the nickname “Mickey” despite have having completely unrelated first names. Grasso was born as “Newton” and Cochrane was given the name “Gordon.”

Grasso’s 1952 Topps card has another point of interest beyond his name and face. Like several cards in the set there appears a red backdrop accompanied by a light halo around the player’s head. Unlike the others, this card includes some confusing work by the artist colorizing the photo. The red background ends at Grasso’s shoulders and is replaced in the area between his torso and glove arm with green. Was the original artwork for the card intended to have a ballpark scene set against a green infield?