A couple years ago, I found myself seated in offices at the World Trade Center complex. My eyes kept drifting to the window, attracted to a series of white flashes of light coming from the Freedom Tower next door. While the flashes initially looked like the visual component of the building’s fire alarm, a closer inspection revealed the light source originated from a chain of photographers recording a parade of clothing models.

This was not a fashion show, but rather a process playing out on an industrial scale. From my vantage point I could see nearly a dozen photo backdrops set in a line perhaps 10 feet from each other. Each backdrop had its own photographer, a pile of related lighting equipment, and a model. The models each went through a choreographed series of rapid poses, each accompanied by the firing of dedicated flash. The models finished their poses simultaneously and stepped in synchronized fashion to the next backdrop. When they had finished the set they reset positions like a typewriter’s carriage return while the photographers moved in unison to pull down their next backdrop.

I suspect the models wanted to see how their images turned out. After all, having their picture taken is their livelihood and a career choice many had spent significant time pursuing. Digital photography has made immediate feedback possible, but professional modeling shots require significant editing before reaching the final state in which they will be presented for public consumption. Honestly, I do not know if the photographers edit the photos themselves or send them to another team for that work. It is possible that none of the individuals present at the shoot have any say on the final product.

That is certainly true in the world of baseball cards. Generally, the person capturing a player’s image and the person responsible for a card’s photo selection are different people. There may be no communication between them, leading to all sorts of issues.

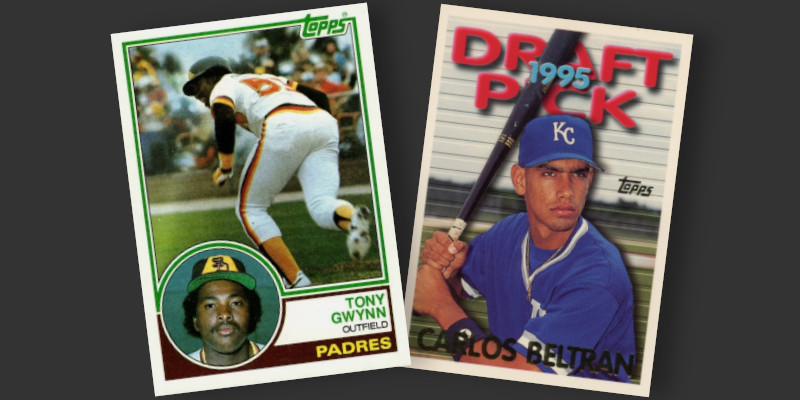

Tony Gwynn was excited to find himself on a baseball card in 1983, only to get upset when he learned Topps had used an unflattering image of him leaving the batter’s box from a 1982 Spring Training game. Gwynn, who had personal issues with his appearance, felt the card made his rear end look huge while almost completely obscuring his face. Doug McWilliams, the card’s photographer, was told directly by the San Diego outfielder that he hated the card. McWilliams could not help but agree. The image had come from a roll of Gwynn related images and was selected by someone at Topps as the best way to introduce the future batting champ to card collectors. The photographer was just as in the dark as his subject.

Perhaps the direct involvement of the player and photographer could head off cardboard controversies. Topps was seemingly getting better at photo selection in 1995 when the editorial staff released the first card of likely Hall of Famer Carlos Beltran. It features a clean design and a solid rookie year photo. The only problem is the fact that the player pictured is not Beltran, but fellow prospect Juan Lebron. It can’t feel good for either player to be asked to sign that card.

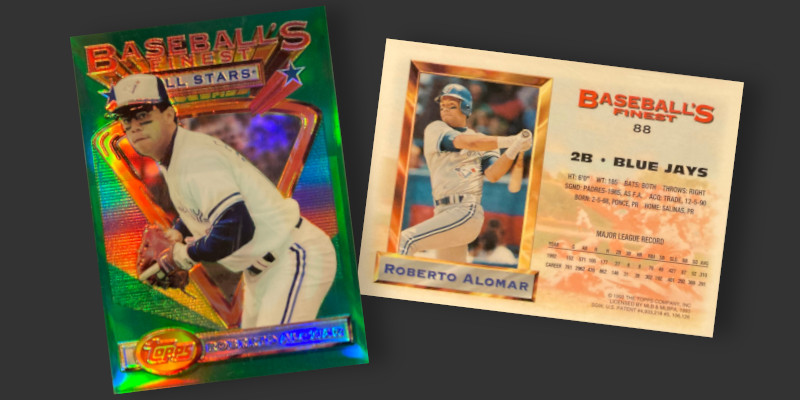

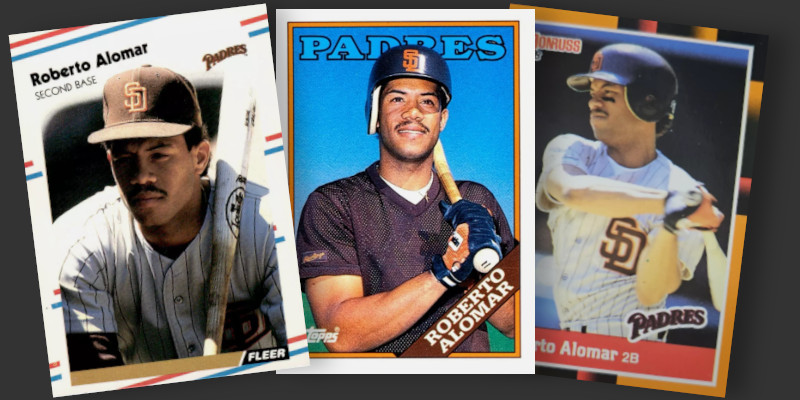

Still, a bad rookie card is a small inconvenience in the grand scheme of things for players who go on to assemble impressive on-field careers. In some regards Roberto Alomar seemed a step ahead of Gwynn and Beltran when his cards began filling out collectors’ binder pages in the late 1980s. His crop of 1988 rookie cards are numerous enough to spill onto a second 9-card page and are almost uniformly good.

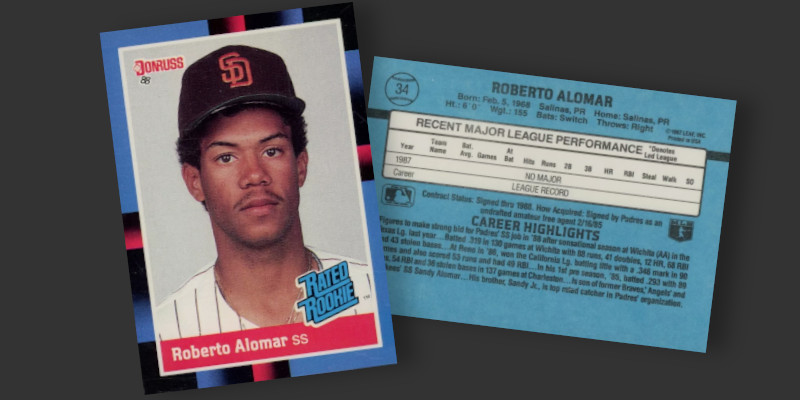

These are very good images for a cardboard debut. Unfortunately, Alomar was well aware of a less favorable rookie card: His Rated Rookie in that season’s vastly overproduced flagship Donruss release. The image appears to have been taken directly from the team’s media kit and depicts a teenage Alomar prior to his ever taking the field for the team. The image looks worse than a driver’s license photo, it looks like it was taken from a learner’s permit. It’s not terrible, but definitely ranks behind the more photogenic offerings of the year.

So why is it so important to know about this haphazardly designed card? The answer lies in Alomar’s personality. While he looks stoic on his ’88 Donruss debut, there is a point where he cannot keep everything inside. Those not close to him have described him as aloof and quickly found themselves in the presence of a very emotional Alomar once the dam breaks. Witness the infamous 1996 incident in which he went from ahead in a 2-0 count to spitting on the home plate umpire and insulting his family in a follow up interview.

Half a dozen years after Alomar almost led MLB umpires to go on strike for a second time in 3 seasons, he was part of a New York Mets team that looked fantastic on paper but were struggling to avoid the NL East basement on the field. Midway through the season someone attached a copy of Alomar’s ’88 Donruss rookie to his locker. Multiple passersby ragged on his photo, to which Alomar initially responded by ignoring the attention. Eventually he had enough, forcefully confronting those that made light of the card (and ruining their tabletop game of dominoes in the process). Roger Cedano pressed the issue the next day, bringing up the card and being subsequently followed from the clubhouse to the dugout by an enraged Alomar. From that vantage point the confrontation and a physical intervention from Mo Vaughn became the focus of television cameras.

Shortly thereafter, the Mets came to Yankee Stadium to take on their American League counterparts. Bronx fans brought enlarged copies of the card to wave across the Upper Deck, hoping to provoke another reaction.

A Lot of Runs From a Guy Known for Defense

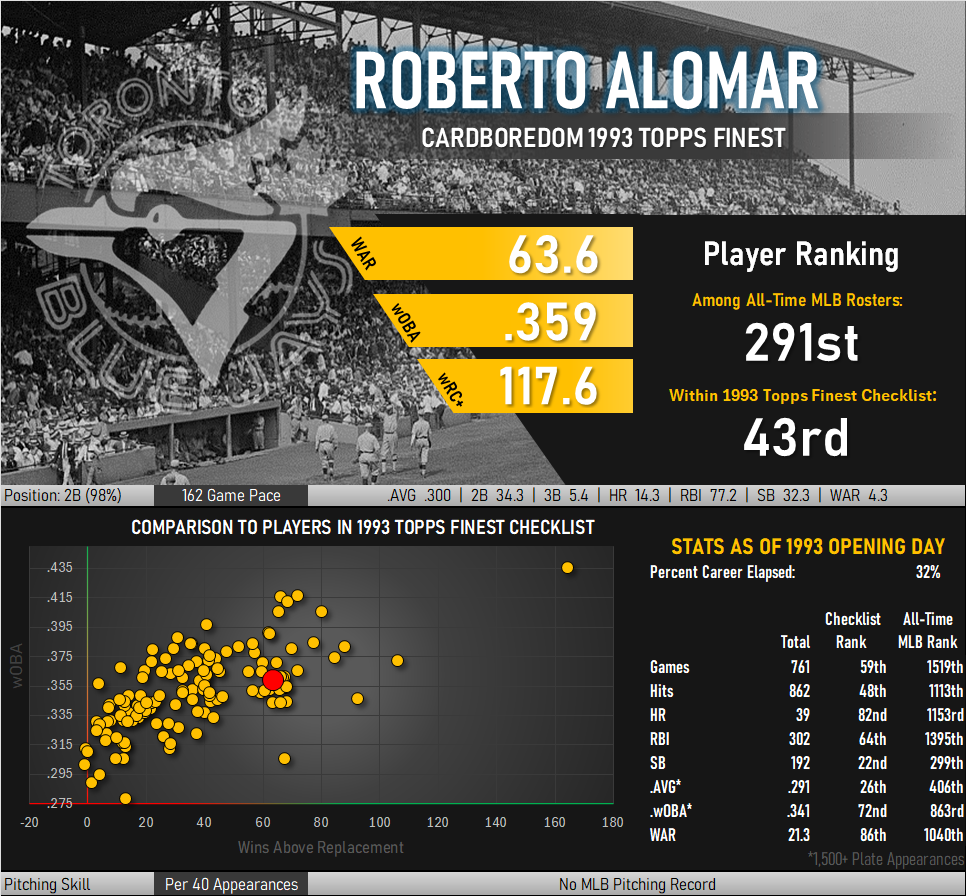

Setting aside the possibility of being thrown off his game by people looking at his baseball card, Alomar was a key part of several teams making playoff runs in the 1990s. Vaunted defensive skill (10 Gold Gloves) and a career .300 batting average are highlights of a career on par with several other second basemen of the period. Alomar’s career effectiveness is about the same as Ryne Sandberg, Lou Whitaker, or Craig Biggio when looked at through the dual lens of WAR and wOBA. Why is it that his name tends to stand out over these other guys?

Take a look at his role on the 1999 Cleveland Indians. The team scored 1,009 runs that season, topped only in the past century by the 1950 Red Sox and a handful of 1930s Yankee squads, teams that had names like Ruth and Gehrig at the top of leader tables. Four digit run production is a rare feat with the ’99 Indians the only team to do so in the last 70+ seasons. Alomar, it turns out, paced this high scoring team in terms of runs scored. Alomar’s Indians of 25 years ago outscored the 2024 Central Division Champion Guardians by more than 40%. Alomar gets remembered for being a fine defensive player who ended up scoring the most runs in a season made historic for run production.