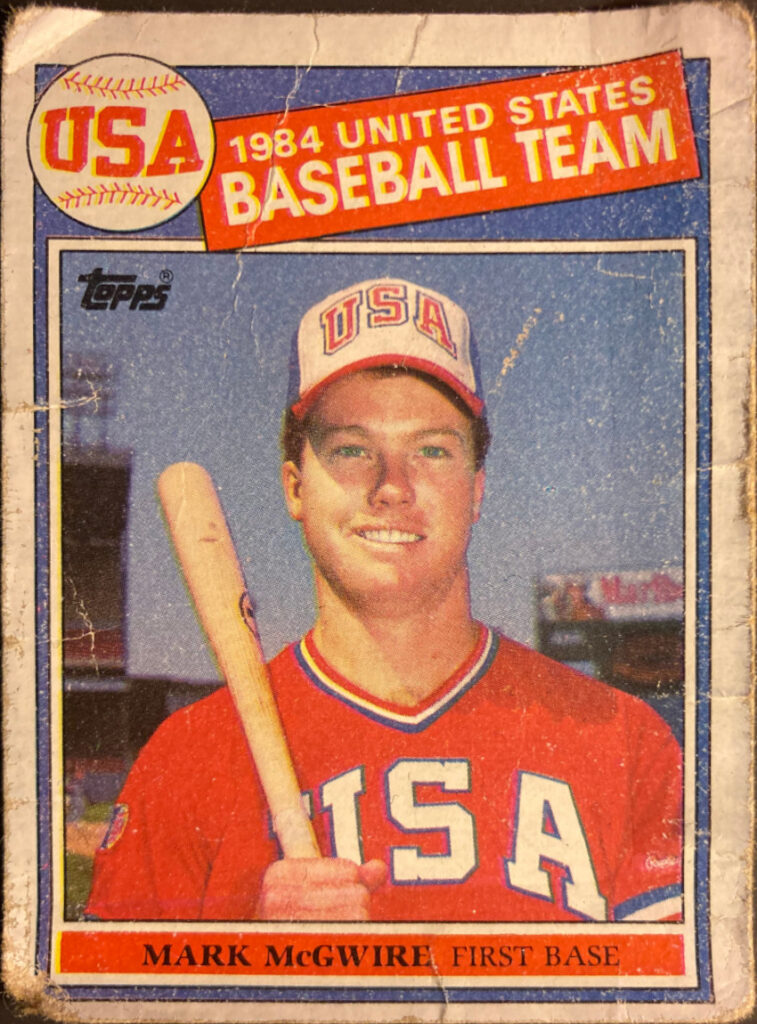

Every year I put a few junk wax era baseball cards inside my wallet and carry them around for the next twelve months. The cards are completely unprotected and rapidly become worn. On my birthday I take the mangled cardboard out and replace it with a selection of new cards to repeat the process. The selection of “wallet cards” that I carried in 2022 included one of the most famous cards of the 1980s.

There is something for everyone in the history of this card. It was produced in large enough quantities to have been a part of almost every collection assembled in the past 40 years. Those looking for the new and greatest thing can look back to a time when this was the most sought-after card of the decade. Prospectors can delight in the knowledge that this card was considered nothing more than a common for the first two years of its existence, changing hands at just a few pennies per copy. Collectors of parallels find the card entering the hobby in the early days of Topps’ limited production Tiffany sets. Fans of true crime have multiple counterfeiting rings and fraud convictions to sort through. Collectors looking for true condition rarities encounter one of the toughest cards of the junk wax era to find in gem mint condition.

Of course, there are also the home runs. McGwire was not your typical longball hitting slugger, but statistically one of the most unique bats in the history of the game. Each decade of the live ball era has seen guys come and go who were capable of launching 40 or more home runs in a season. Unlike many who would constitute a list of these names, McGwire was a threat to do so over the entire course of his career rather than a 5-10 year performance peak. He set a record for home runs as a rookie with 49 in 1987, a mark that stood for three decades. He hit 70 home runs in 1998 and followed up that performance with 65 more in 1999. These bombs came at career average of one every 13.1 plate appearances, blowing away the 1 HR per 14.6 rate that separated Babe Ruth from every other human being who held a bat. McGwire’s lead over Ruth in this metric is the same size as the distance from 2nd place (Ruth) from 6th/7th place.

These home runs made McGwire infamous as well as famous. His name is forever connected with the Steroid Era, with Big Mac featuring prominently in the on-field fireworks as well as the high profile inquiries into the sport. It was his soundbites and denials that made the news, not those of the lesser names contained in the Mitchell Report. He ultimately admitted to HGH and PED usage in a 2010 interview, bringing some closure to the issue nearly a decade after he left the game. By that point public opinion had already crystalized for or against the slugger to the point where one could say, “guys like McGwire” and everyone knows what is implied. The PED scandals of 1990s baseball are slowly resembling the 1919 Black Sox gambling scandal with McGwire playing the role of Shoeless Joe Jackson. Did he cheat? After initial denials, a pile of testimony and a confession eventually emerged to answer the question. Could he have still been one of the greatest without the controversy? People still argue about Jackson to this day. 100 years from now people are likely to argue about the would’ve-could’ves of Mark McGwire. They’ll be holding this card when they do it. No other card comes close to capturing the collecting public’s imagination when someone says they have “the” McGwire card.

A Closer Look at the Card

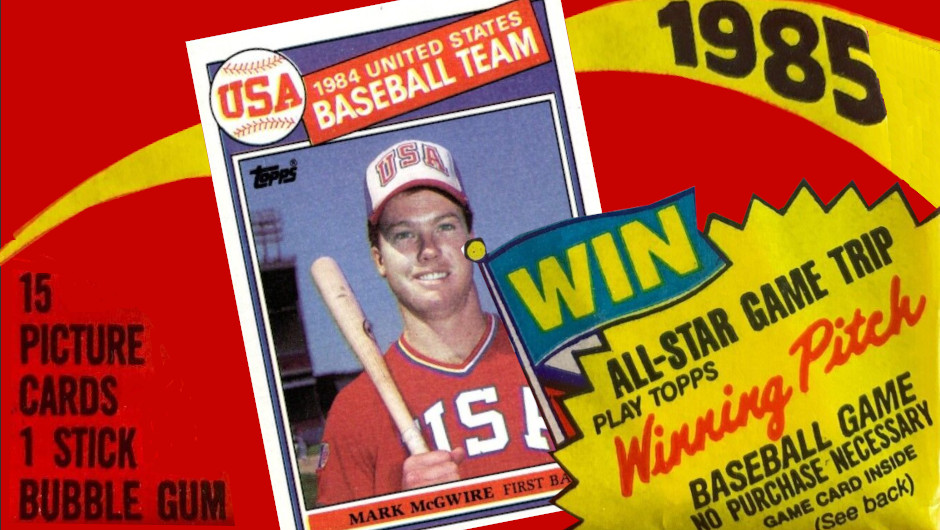

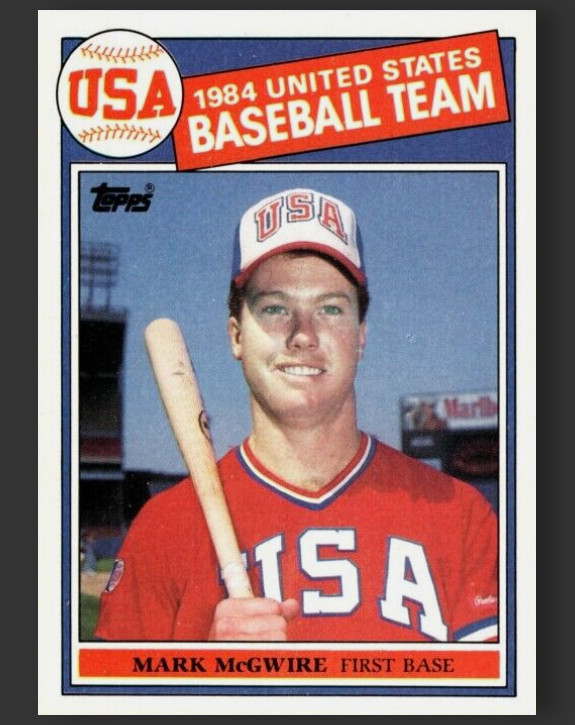

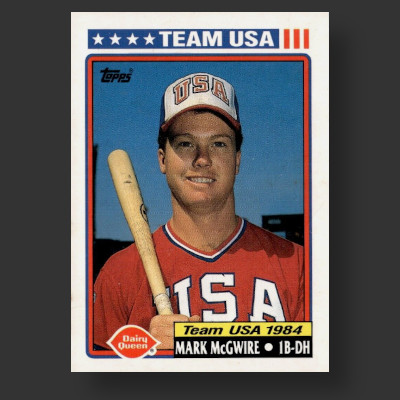

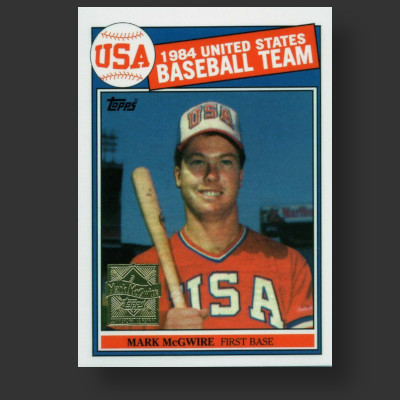

The Mark McGwire card included in the 1985 Topps checklist depicts a smiling Mark holding a baseball bat. The card was part of a distinct subset highlighting 16 of the members of the 1984 US Olympic Baseball Team in the ’85 Topps release. These cards represented players whose amateur status had ended and included future MLB names Cory Snyder and Shane Mack. Others were omitted, such as Will Clark and Barry Larkin, who returned to school and preserved their amateur status by avoiding Topps’ licensing payments.

Baseball in the Olympics was a novelty. The games were hosted in Los Angeles in 1984 and the national pastime was included for the first time in two decades as a demonstration sport. The game would again appear in a non-official medal eligible demonstration status in 1988 before becoming an official Olympic sport in the 1992 games.

While this card was issued in 1985 and shows McGwire wearing the red white and blue of Team USA, he had yet to take a swing in the Olympics when the picture was taken. The photograph was taken during a 38-day exhibition tour that saw Team USA play 32 games in stadiums across the country heading ahead of Olympic competition.

McGwire stated in a 2014 interview that the photo was taken at Shea Stadium in New York, though an eagle-eyed (and correct!) reader pointed out that this is actually Cleveland Stadium. McGwire’s memories of the day are tied to the fact that he is portrayed holding a wood bat. McGwire and his teammates used aluminum bats, not wood, in their NCAA and exhibition games. Knowing in advance that Topps would be photographing the team for an upcoming baseball card, he went to a sporting goods store and purchased a Louisville Slugger for the occasion (McGwire used Rawlings bats throughout his MLB career). The wood bat is indeed a good look with McGwire the only player featured with a bat on any of the Team USA cards. The camera angle and positioning of the bat next to McGwire’s 6’5″ frame makes it look like a Little League model.

The photo features something in the background that was common at the time: A giant Marlboro cigarette billboard. Stadium tobacco advertising would continue to find its way onto baseball cards through the rest of the decade. While the ads didn’t disappear from ballparks until the middle of the next decade, designers of baseball cards began to edit them out of photos or simply avoid using ones with visible ads all together. The images are seen so rarely at ballparks today that the Marlboro ad’s presence is a bit jarring to those who have never seen it before.

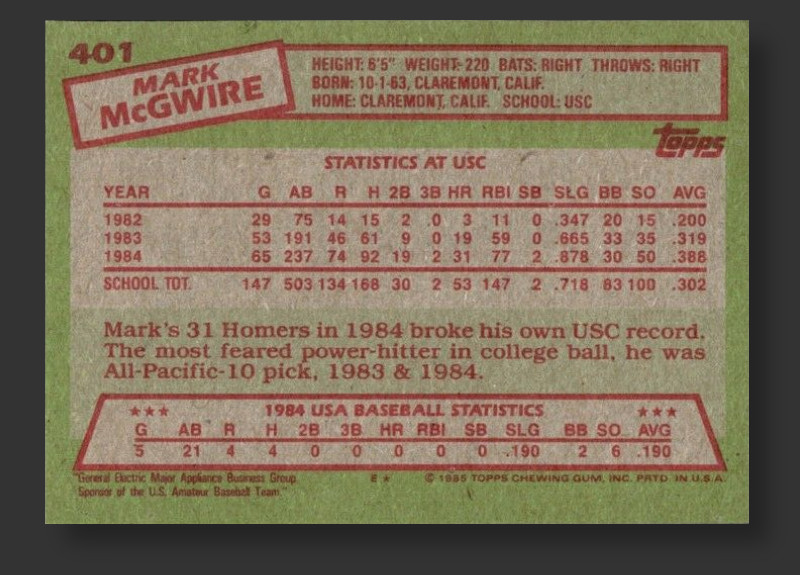

The back of the card is printed in red ink on the usual pea green cardboard used by Topps throughout the 1985 set, a design choice that must have been havoc for collectors with red/green color blindness. Viewers are presented with batting stats for McGwire’s three year college career at USC. Omitted are his 7-5 pitching record and sub-3.00 ERA that were earned in his first two years. McGwire only played through his junior year and it is unclear to me if he finished his degree outside of sports or left school early to declare for the MLB Draft.

The biographic text below his college stats mentions that he broke the school record for home runs twice. In a bit of foreshadowing of the career that was to come, the statistical table above shows that he not only set a new record but exceeded his old one by more than 60%.

There appears one more goodie near the bottom of the card. Just below a table of his 1984 Olympic performance lies the copyright line. To the left of the copyright is a notation that Team USA is sponsored by the General Electric Major Appliance Business Group. There has to have been some sort of legal requirement in Topps’ licensing deal requiring it to include GE’s sponsorship on the card. What makes this extra funny is the fact that it isn’t just GE sponsoring the team, but a very specific operating division of the conglomerate doing so.

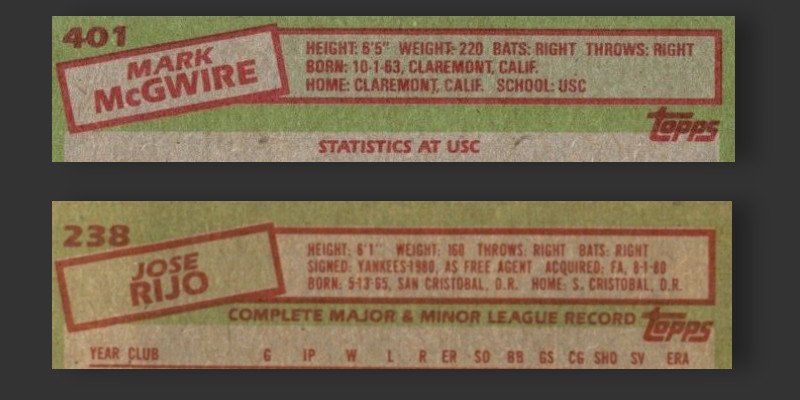

Topps slightly changed the backside design of its Team USA cards in comparison to other cards in the set. 1985 Topps cards display a player’s name alongside height, weight, and other demographic information in a pair of boxes near the top of the layout. On most cards the background of the box containing the name is comprised of a shade of green similar to that of the card’s border. The demographics box is filled with a non-inked background similar to what lays behind the player’s career statistics in the middle of the card. The Team USA cards transpose this color combination, giving a green hue to the demographics and leaving the player name without background coloring.

Topps in 1985

Prior to the 1980s Topps had spent much of the past 25 years as the only major baseball card manufacturer chronicling the sport. A series of lawsuits by the Fleer Corporation eventually broke open competition and led to the introduction of a three-way race for hobby supremacy. Beginning in 1981, collectors could not only find their familiar Topps offerings on retailer’s shelves, but cards from Fleer and Donruss as well. Earlier reviews were pretty much unanimous: Topps was far and away the best of the three. The new entrants’ cards suffered from low quality photos, spotty quality control, and unappealing aesthetics.

That opinion still held in 1985, though two factors were emerging to strain Topps’ grip on the market. Donruss and Fleer had significantly improved their offerings the prior year, garnering accolades from collectors. Both brands again launched well received products in 1985, though at least one hobby publication referred to Fleer as having a history of producing “dull and predictable” offerings in the past.

While appreciate of the improved designs, few were shifting their buying habits towards what were still seen as second tier producers. The good news for Donruss and Fleer was that the card collecting hobby was exploding in popularity. Both companies’ ’84 offerings were considered relatively low print run issues, though in reality both had run the presses throughout the year to meet demand. The cards weren’t rare, they were just experiencing the first time that demand began to outstrip supply. Topps continued to rake in the majority of industry revenue, but each incremental dollar coming from new collectors was leaning more towards its rivals’ products. Price guides in 1985 reported Donruss’ set regularly commanded a higher price than Topps.

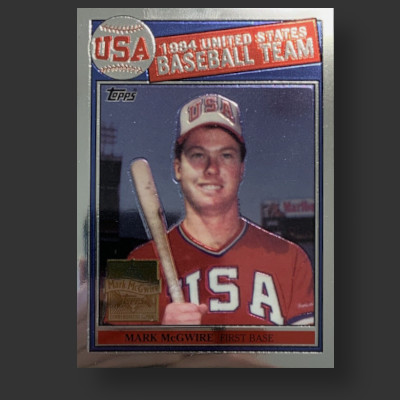

This period directly generated a couple of innovations from Topps that in turn created the McGwire cards that were to become so coveted. Responding to improved competition in 1984, Topps produced a parallel version of its regular 1984 set that was distributed only through hobby channels. These cards could be differentiated from their base peers by high levels of gloss on the front side and bright white card stock on the back. The set, marketed only as the “Collector’s Edition,” was limited to a print run of about 7,000 copies and would eventually become known as “Tiffany” cards. Topps brought the idea back again in 1985 along with a serial numbered (on the box, not the card) production run of 5,000 copies.

An increasing hobby focus on rookies and exclusive licensing deals led to another development for Topps: The introduction of Team USA cards. The card producer included 16 members of the national team in its regular ’85 set. Topps brought the idea back again in 1988 Traded and 1992 Traded instead of waiting for the year after the Olympics in order to capitalize on interest in the games. These Olympic cards were omitted from the O-Pee-Chee set, a similar set nearly identical to Topps and produced for the Canadian market.

Printing and Distribution

Topps was engaged in its longstanding practice of producing cards on large sheets of 132 subjects. McGwire’s card was printed on a sheet containing cards of Dwight Gooden, Bret Saberhagen, Pete Rose, and 15 of the 16 Team USA cards. The McGwire card is situated on the first column of the next to last row. This gives his card three neighbors in the form of cards of Scot Thompson, Jim Dwyer, and a mustachioed Jack Perconte. As a result, severely miscut versions of any of these cards may contain traces of a McGwire rookie. As a resident of one of the borders of the printing sheet, the McGwire card can be more difficult that cards with other placements to locate with perfect left/right centering.

While Topps sold some full sets of cards in uncut sheet form, the vast majority of that year’s issue was distributed in an array of packaging.

| Distribution Method | # Cards Included | % Chance of Finding McGwire |

|---|---|---|

| Factory Set | 792 | 100.0% |

| Rack Box | 1,152 | 77.7% |

| Cello Box | 640 | 57.8% |

| Wax Box | 540 | 49.8% |

| Vending Box | 500 | 46.8% |

| Rack Pack (sight unseen) | 48 | 6.1% |

| Rack Pack (no McGwire showing) | 48 | 5.3% |

| Grocery Rack Pack (sight unseen) | 42 | 5.3% |

| Grocery Rack Pack (no McGwire showing) | 42 | 4.5% |

| Cello Pack (sight unseen) | 28 | 3.5% |

| Cello Pack (no McGwire showing) | 28 | 3.3% |

| Wax Pack | 15 | 1.9% |

How Many McGwire Rookies Were Produced?

Topps and other major card manufacturers of the 1980s did not provide collectors with production numbers for the cards entering their collections. Aside from acknowledging through financial statements that print runs of the era were much, much higher than the preceding decade, Topps was not inclined to tell card purchasers much more information. Thanks to a clue provided by a Topps marketing stunt we can with high confidence estimate a floor for the number McGwire rookies produced.

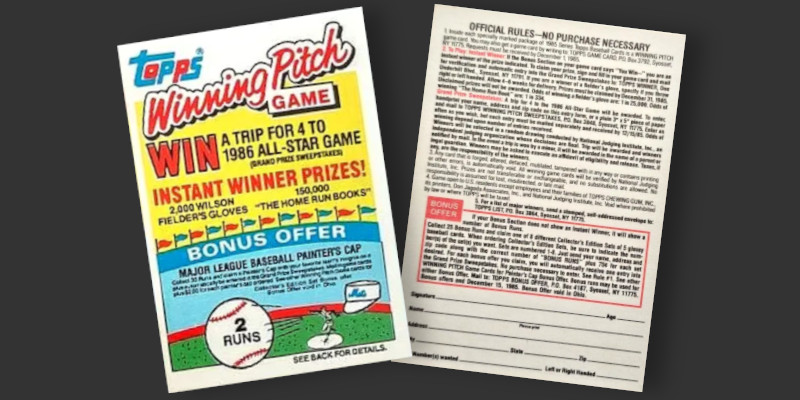

In 1985 Topps wax and cello packs contained card-sized game pieces for a promotion titled the “Winning Pitch Game.” The contest consisted of three levels of prizes. A grand prize trip to the 1986 All-Star Game was the centerpiece of the promotion with the winner selected from all participants who had filled out the back of the game pieces with their contact information. To encourage recurring purchases of Topps products, most of the game cards included a number of “runs” inside a cartoon baseball placed at the bottom of the game piece. Collectors who gathered enough of these could send them to Topps in exchange for 5 cards from Topps’ 40-card All-Star Glossy Commemorative set (25 runs) or a team-themed painter’s cap (30 runs).

Most game pieces contained 2-8 runs, though 152,000 of the game inserts were instead instant winners of two different prizes. Winning pieces could be exchanged for a book or a baseball mitt. The book constituted the majority of instant win prizes, supplying 150,000 of the winners. Titled The Home Run Book, the red white and blue paperback is entirely focused on what makes home runs so arresting and features short biographical sketches of the sport’s most prolific hitters. The remaining 2,000 instant win cards entitled bearers to one of 2,000 baseball gloves.

These instant win prizes form the basis for estimating the number of 1985 Topps cards produced. Contained in the small print of the terms and conditions of the contest are the odds of becoming an instant winner. Winning claims on books were inserted at a rate of 1 in 334 and gloves were given away at a ratio of 1 in 25,000. Because both the odds and number of prizes are known, one can calculate the number of game pieces produced. With game pieces inserted at a rate of one per pack, it is a simple exercise to determine the number of packs manufactured and by extension the number of cards distributed within them.

150,000 Instant win books multiplied by the 343 packs needed to find each one yields a total of 50.1 million packs. 2,000 baseball gloves multiplied by 25,000 game pieces needed to find an instant winner indicates an even 50 million packs were made. I do not know what accounts for the implied difference in production, but feel it can be ignored given that it represents a deviation of just 0.2%. Wax packs from Topps each included 15 cards in 1985. 15 cards per pack multiplied by 50 million packs indicates 751.5 million cards for that year’s issue. Dividing this total by the 792 names in the checklist implies production of 948,864 for each card.

This is not yet a good approximation of the number of cards produced. Topps placed game pieces in wax packs as well as cello packs. While the number of game pieces in both packaging types is already accounted for, the number of cards contained in each pack differs. Cello packs contained 28 cards instead of the 15 found in wax wrappers. Topps did not break down the allocation between packaging types, though my hobby experience shows wax to have been the most popular distribution method. The table below shows estimated production levels based on various potential splits of wax/cello sales and an estimated 50 million game pieces.

| Ratio of Wax:Cello Game Pieces | 95/5 | 90/10 | 85/15 | 80/20 | 75/25 | 70/30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wax Packs | 47,500,000 | 45,000,000 | 42,500,000 | 40,000,000 | 37,500,000 | 35,000,000 |

| Cards Distributed via Wax | 712,500,000 | 675,000,000 | 637,500,000 | 600,000,000 | 562,500,000 | 525,000,000 |

| Cello Packs | 2,500,000 | 5,000,000 | 7,500,000 | 10,000,000 | 12,500,000 | 15,000,000 |

| Cards Distributed Via Cello | 70,000,000 | 140,000,000 | 210,000,000 | 280,000,000 | 350,000,000 | 420,000,000 |

| Total 1985 Cards Produced | 782,500,000 | 815,000,000 | 847,500,000 | 880,000,000 | 912,500,000 | 945,000,000 |

| Production (McGwire) | 988,005 | 1,029,040 | 1,070,076 | 1,111,111 | 1,152,146 | 1,193,182 |

Based on the matrix above there appear to have been 1-1.2 million of each 1985 Topps card distributed via the wax and cello distribution channels. While these represent the methods by which Topps conducted the Winning Pitch promotion, it was not the only way in which the firm sold its cards. Topps produced factory sealed sets by the case. Rack packs were made in varieties containing 42 or 48 cards. 500-card vending boxes were still being sold for the wholesale market as well. Each of these packaging forms are readily encountered by those looking for 1985 cards, indicating their production was fairly substantial. Given the large number of cards contained in these bulk distribution forms and their high levels of availability today, I would posit that our 1-1.2 million card estimate can be bumped by at least 25%. Based on this assumption I conclude there at least 1.3 million 1985 Mark McGwire rookies and likely as many as 1.5 million.

Those Cards Looks Familiar

Popular cards get printed over and over again. Topps has reached back to its 1952 design countless times in an effort to connect with collectors. The company produced copies of earlier cards as far back as 1974 when it produced a handful of Hank Aaron cards picturing his earlier Topps issues. 1975 saw the introduction of MVP cards displaying earlier cards from players’ award winning seasons. Turn Back the Clock became a popular subset highlighting earlier card issues for nearly a decade in the 1980s.

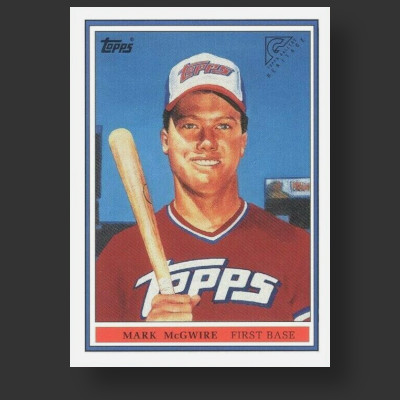

Team USA baseball had more marketing opportunities when the sport became an official medal contending event in the 1992 Olympics. GE’s appliance division was no longer the driving force funding the team, opening the path for other marketing opportunities. Ice cream restaurant chain Dairy Queen commissioned Topps to manufacturer a special set of 33 baseball cards commemorating past and present Olympic lineups. Topps broke out McGwire’s popular photo for use in this issue, while other players had different images selected. Topps did make a few adjustments for Dairy Queen, notably tightening up the photo’s cropping and artfully removing the cigarette ad from behind McGwire’s left shoulder.

The ’85 McGwire rookie reached its peak popularity at the turn of the century, prompting Topps to issue new versions of a now classic card. I count six distinct cards inside of a three year range.

Topps’ first series of baseball cards were issued in December 1999. Inserted at a rate of 1:36 packs was a reprint on modern card stock commemorating Topps’ first inclusion of McGwire in a set issued 15 years earlier. Aside from a glossy finish and different card stock, the reprint is identified by a gold stamp in the lower left corner of the photo and the addition of a 1999 copyright line. This copyright notice has caused confusion years later for collectors just discovering the card. A search of eBay reveals dozens of sellers referring to the card as a 1999 issue. The date serves another purpose, getting the cards into the open prior to Upper Deck’s 2000 licensing deal with Team USA.

Three parallel varieties of the ’00 reprint were made available to collectors in addition to the insert appearing in packs of the base Topps cards. Topps brought back the idea of its “Tiffany” sets of 1984-1991 with a special version of the 2000 set. Billed as “Limited Edition” and sold only as a factory set in hobby shops, this product was limited to a production run of only 4,000 of each card. Each card is differentiated from the regular variety by a stamped “Limited Edition” in gold foil near the bottom of the main photo. The Limited Edition sets contained not only each of the 488 base cards in the checklist, but one of each insert as well, including a McGwire bearing the Limited Edition stamp.

As it had done since 1996, Topps produced a parallel version of its regular baseball cards using chromium printing. The cards, marketed as Topps Chrome, are considered a separate set and were distributed in their own packaging through hobby channels. Although Chrome cards were produced in smaller numbers than their regular Topps counterparts, the ’85 McGwire insert was pulled from Chrome packs at a higher rate (1:32 odds vs. 1:36). As with Topps’ other chrome sets, a refractor version was produced in much lower quantities with collectors needing to open more than 12,000 packs in order to find the ’85 reprint refractor that was limited to a print run of just 70 copies. Issued three months after the base Topps version, both Chrome cards feature a 2000 copyright date instead of 1999.

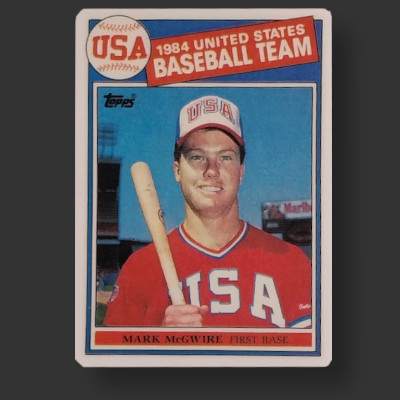

Topps sort of reprinted the card again two years later. While not technically a card, a version was produced on porcelain and sold directly to consumers via newspaper advertisements. This oddball issue features rounded corners with the back of the card placing a copy of the reverse side of McGwire’s ’85 Topps card inside a thick white border. This border contains a notice stating the card was made by R&N China under license from Topps and is hand numbered out of 10,000.

Topps didn’t completely sit out 2002, the first year without McGwire on the diamond following his surprise off-season retirement. That summer the card manufacturer included him in its Heritage line of inserts appearing in packs of Topps Gallery. Gallery, as its name suggests, is a release focused on artistic interpretations of players with each card using a painting rather than a photo as the primary focus. McGwire’s card is based upon the famous ’85 Topps issue, but has the design cleaned up to remove the large Team USA references from the top of the card. The Olympic scrubbing isn’t limited just to design elements, as Topps logos replace the block USA lettering on his jersey and cap. Given that Upper Deck’s Olympic licensing deal was in full swing and Topps had issued several McGwire commemorative cards in the recent past, I wonder if Upper Deck’s legal team had reached out to their longstanding rival.

Counterfeits. Lots of Counterfeits.

Of course, Topps was not the only one to print additional copies of this popular card. Counterfeiters were already hard at work as soon as McGwire picked up his Rookie of the Year Award at the end of the 1987 season. The Washington Post reported in 1988 on an influx of fake McGwire rookies confounding collectors in California.

A decade later Beckett Baseball Card Monthly began regularly posting a warning about counterfeits at the top of the price guide’s table of 1985 Topps cards. The publication’s editors noted that “a number…have surfaced in recent months.” The warning, which appears as a single sentence for other frequently faked cards, then goes into detail about what to look for in determining authenticity. Collectors are encouraged to use at least 8x magnification to perform these tests. Smelling the cardboard is even recommended as a method for making sure the McGwire card in hand is legitimate. Sports Collector’s Digest referenced the fact that there had been multiple waves of counterfeit issuance, calling the output from the 1998 surge “the scariest yet” in terms of realism.

It was around this time that the McGwire rookie got sucked into the expanding web of Operation Bullpen, an FBI investigation into a memorabilia forgery ring. A small number of the forgers opened a side hustle faking a handful of popular 1980s sports cards that included McGwire. A local print shop was hired to produce thousands of 36-card sheets of the targeted cards, resulting in fakes being sold in bulk to a network of waiting dealers. Six people plead guilty to participating in the McGwire scheme in 2001.

More than 50,000 counterfeits cards were intercepted through Operation Bullpen, though a five-figure number escaped into the wild. Given that 15,000 or so represents about 1% of Topps’ original 1985 production, potential buyers of a McGwire rookie are faced with a not insignificant chance of encountering a fake. A recent reading of a [now deleted] Reddit post revealed a collector who reported finding a brick of 1,000 McGwire rookies in his father’s collection. Considering the quantity of cards and the fact that this would have been worth about a quarter million dollars in the late 1990s, I find it likely that these represent one of the bulk dumps of the era’s counterfeits.

Methods for Detecting a Fake McGwire

With so many fake versions of this card circulating, how does one go about making sure the one they are looking at is the real thing? The are more than a dozen “tells” that give away fakes. Given that the card has been copied in multiple waves of varying quality, collectors should utilize varied combinations of these tests to ensure authenticity.

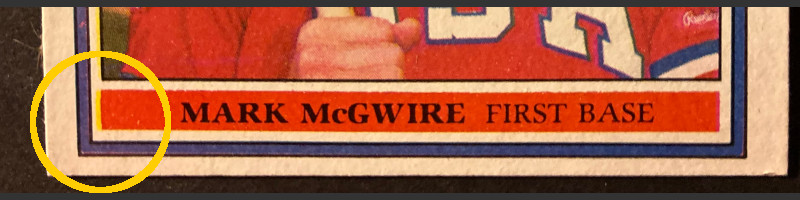

Let’s start with the front of the card and one of the most visible tests. Real cards (and some of the better fakes) have a bit of yellow ink that is slightly misaligned with the name line at the bottom of the card. If that yellow line is not present, run away from the card. Similar misalignment can be observed inside the “1984 United States Baseball Team” text at the top of the card.

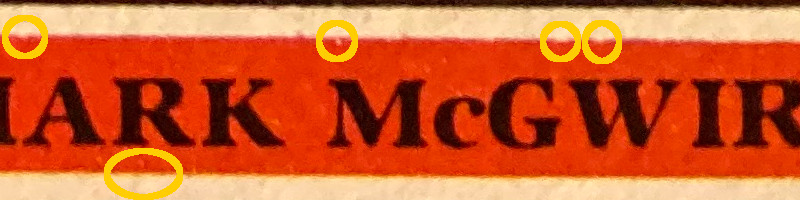

Not only do originals have a bit of a quality control issue with yellow ink, they do not have the cleanest lines at the edge of the text box containing McGwire’s name. The border where the red ink filling meets the white cardstock background is full of small variations on Topps’ originals. Some counterfeits were designed with perfectly straight borders of this area, giving the fakes away to those armed with the capability of viewing the card under magnification.

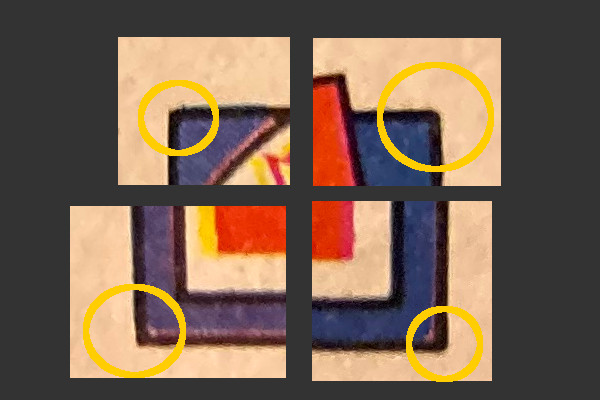

The black borders separating the blue and white design elements are another area that can be checked under magnification. Under close inspection the black ink appears as a solid color on 1985-issued cards. Counterfeits are usually produced using more modern techniques that reproduce colors using small dots of pigment. These dots are visible upon 8x-10x magnification of a fake.

Another telltale clue from the border region is the way the black outlines appear at corners. Many fakes display perfectly square borders that come together in sharp, 90-degree points. Original ’85 Topps cards do not exhibit this pattern, instead coming out of packs with slightly rounded corners in these regions. Close inspection of some fakes reveals some lines where drawn with an incorrect length in editing software, overshooting the intersecting line by a small amount.

There are even more areas that can be checked for authenticity on the front of the card. The blue sky in the photo background will appear under magnification with a distinctive cross-hatch pattern. The same area of a fake card will instead show a series of small dots that blend together to form various shades of blue. Colors on fakes are usually very vivid, displaying deep red on McGwire’s jersey. Originals left the Topps production facility with various amounts of ink, resulting in jersey colors that can be just as vivid as those on counterfeits to some that look almost orange or pink. A card exhibiting one of these “off” colors is much more likely to be real than one picked at random. Greater vigilance should be exercised when a particularly well colored example is encountered.

While colors are very sharp on fakes, the overall quality of the photo is not always so. If you have ever made copies of a copy of a copy you will be familiar with this effect. Many counterfeits were originally constructed by photographing an original card, resulting in an ever so modest reduction in quality. Other fakes were constructed from scratch in photo editing software with the original 1984 photograph overlaid with newly created versions of the 1985’s familiar design. Some of the most prolific fakes used this method with the forgers getting a few details wrong. The baseball emblazoned with “USA” is not perfectly round on these forgeries. In addition, the photo is cropped differently than the original. The “A” in McGwire’s Team USA jersey lines up differently with the “first base” text at the bottom of the card. On these fakes there is no stripe visible on McGwire’s sleeve in the lower right corner while originals clearly show a little triangle of red peeking above the corner of the photo. These counterfeits also prematurely cut off the Marlboro sign in the background, ending the right border of the image through the letter “b.” Original cards cut off the image through the letter “o.”

The back of the card also offers avenues for detecting fakes. The small print in the copyright line and the “General Electric Major Appliance Business Group” advertisement have proven difficult for counterfeiters to render with the same clarity of the Topps original. Close magnification of these areas will reveal slightly blurry text on many forged examples.

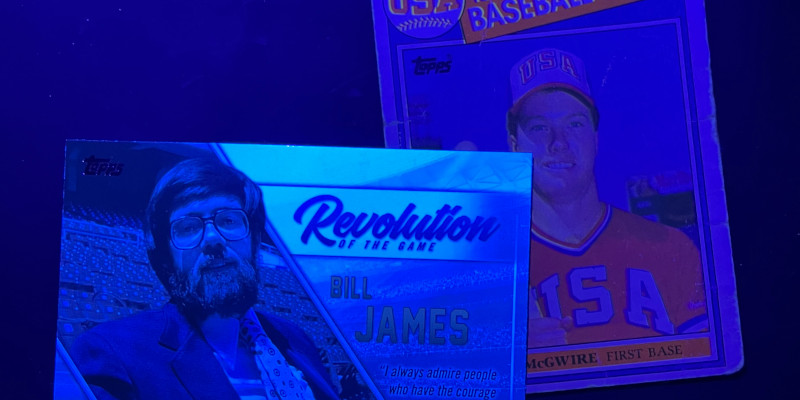

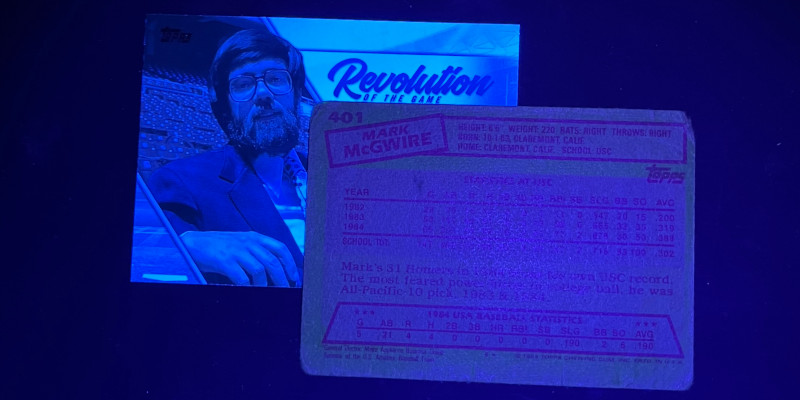

A black light can also be helpful in determining if the correct ink and card stock is present. The composition of the generally available commercial supply of these inputs has changed since 1985. Original cards of the era do not show much reaction when subjected to black light while the lighter color portions of modern printing exhibit bright fluorescence. If your McGwire rookie glows, set it aside immediately as a modern counterfeit.

One important thing to remember about differentiating counterfeits from originals is that these tests need to be performed as a group. Any fake can likely pass one or two of these tests, but passing all of them is a much taller order.

Third Party Grading Data

The ’85 McGwire rookie is one of the most seen cards by the hobby’s major third-party grading services. BGS, PSA, and SGC have combined to assess more than 83,000 of these red, white, and blue pieces of cardboard. Reflecting its leading market share, PSA accounts for 60,542 of these slabbed cards. BGS reports 14,893 on its roles and SGC shows 7,669 in its own population report. Of these, 497 received a grade of gem mint.

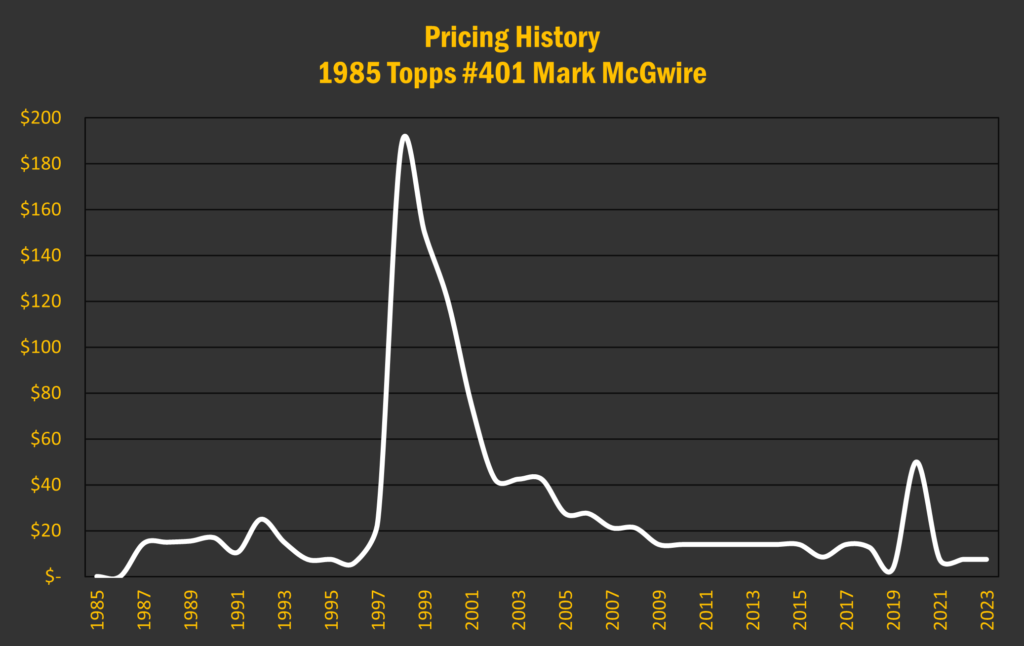

Collector Demand Over Time

The McGwire card was largely overlooked by card collectors when it first came out of Topps wrappers in 1985. There was no notice taken in hobby price guides until he began swatting home runs at a record pace in 1987. In August of that year his name first appeared in Beckett’s Hot List, debuting just behind Pete Incaviglia and ahead of Roger Clemens in position #12. By the end of the season his name was ranked as the most sought after among the magazine’s readership and remained there for a full year before being displaced by Jose Canseco and his 40/40 season. Beckett readers still ranked him as the second best player at the end of the year and the editors responded by putting McGwire and his 1985 Topps rookie on the back cover of the December issue.

The card would largely hold collector interest at steady levels into the early 1990s. Demand slumped following a series of injuries and the 1994-95 players’ strike. McGwire’s home run chase in 1998 (and the 60+ HR season that followed) launched the ’85 rookie card into the stratosphere where it became the top card of the 1980s. The card began a gradual, if not steep, decline in price as the novelty of the ’98 season wore off and Barry Bonds’ exploits relegated McGwire’s record to second place. Allegations of PED usage weighed on sentiment for the next two decades, depressing demand for the McGwire rookie as well as baseball cards in general. A resurgence was seen in 2000 amid the hobby’s miniature “covid-boom.” McGwire rookies have largely returned to recent trends and can be found for under $10 if one is willing to forego the upper end of slabbed material.

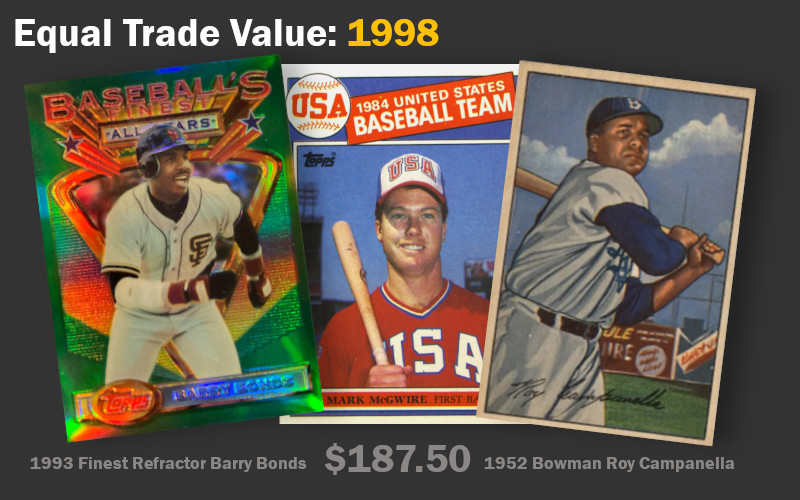

The size of the 1998 price spike doesn’t do justice to the degree of eagerness collectors were expressing at the time to acquire the card. Not only were hobbyists paying hundreds of dollars to get an example into their collection, they were doing so at just the moment that third party grading services were hitting the mainstream. Prices as high as $3,500 were reported for Gem Mint examples in 1998 and were matched again at the height of 2020’s renewed interest. Beckett was reporting graded Gem Mint examples changing hands at $4,500 to $6,000 a pop in December 2000. The highest price I have come across for a Gem Mint Tiffany version of the card is a $27,800 auction carried out on eBay in 2020.

Trade Bait

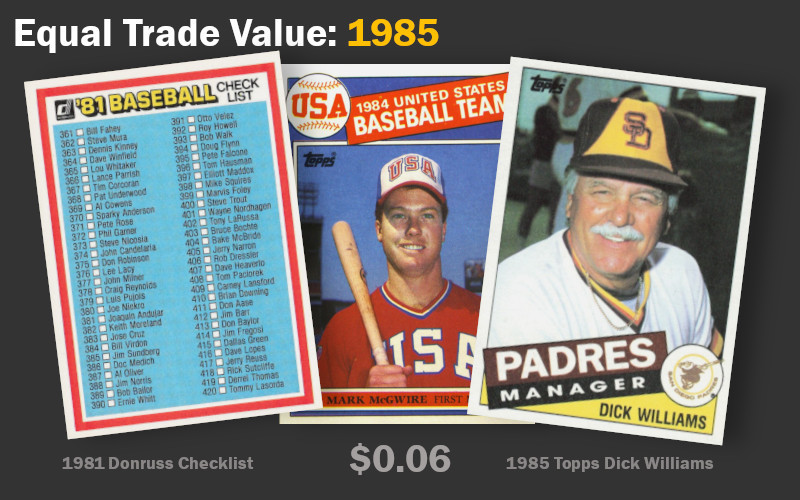

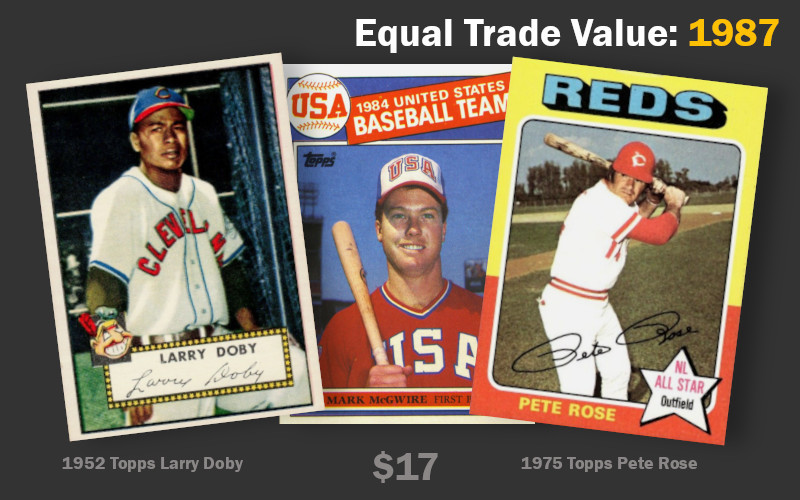

The last century has seen baseball cards as the most popular form of trading card. The operative word is “trading,” as that was the method by which collectors generally assembled collections during much of this time. The question of what constitutes a fair trade has generally been a subjective one. Sometimes it can be as simple as swapping all one’s Chicago Cubs cards for St. Louis Cardinals. An exchange of two friends’ favorite players also seems to be within the general bounds of propriety.

That’s not the way it worked when I was introduced to cards. We were a bunch of sharp-elbowed, greedy little monsters when it came to our cardboard. It’s understandable, as the price guides and regulars at the baseball card shop were telling us these things would one day be worth a fortune. To arbitrate fairness in any trade, all the neighborhood kids abided by an unofficial code in which the values published in Beckett Baseball Card Monthly would dictate what constituted equal value for all parties. If anyone wanted to trade away their favorite 1987 Topps card, they needed to be offered something of the same value in exchange. Other kids watching a trade take place would eagerly note any price discrepancy and rectify it by grabbing cards from your collection to even everything out.

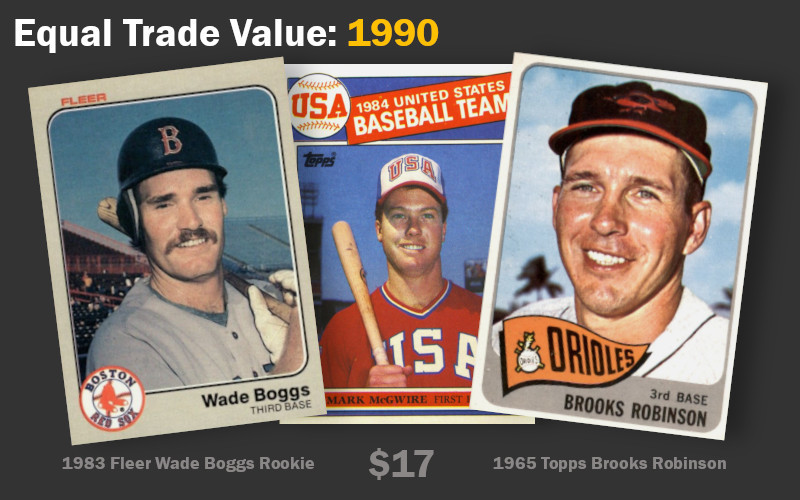

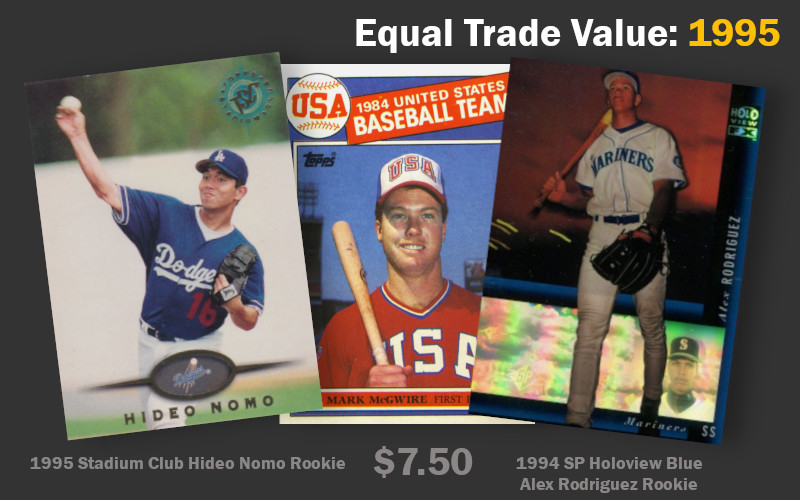

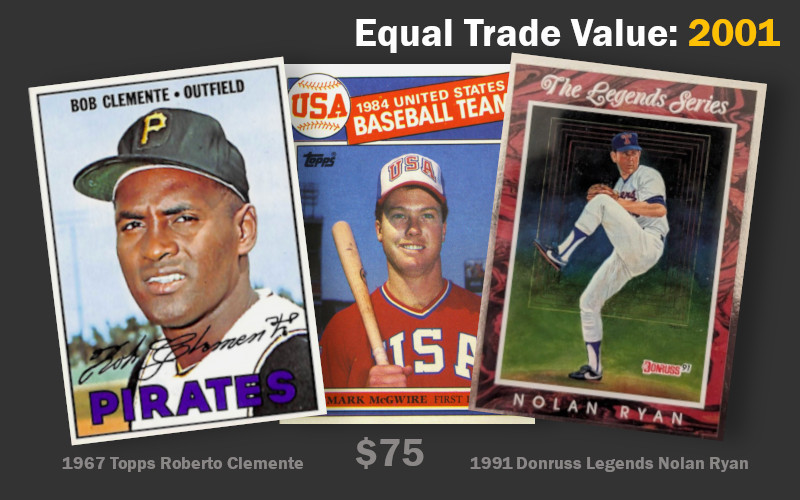

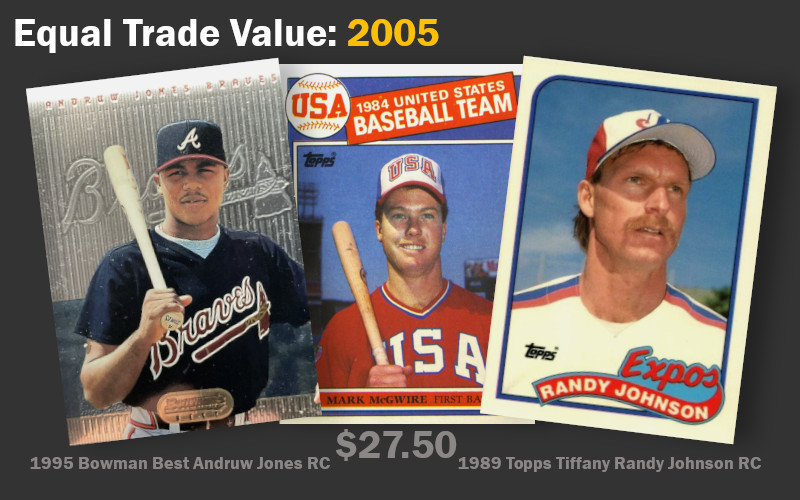

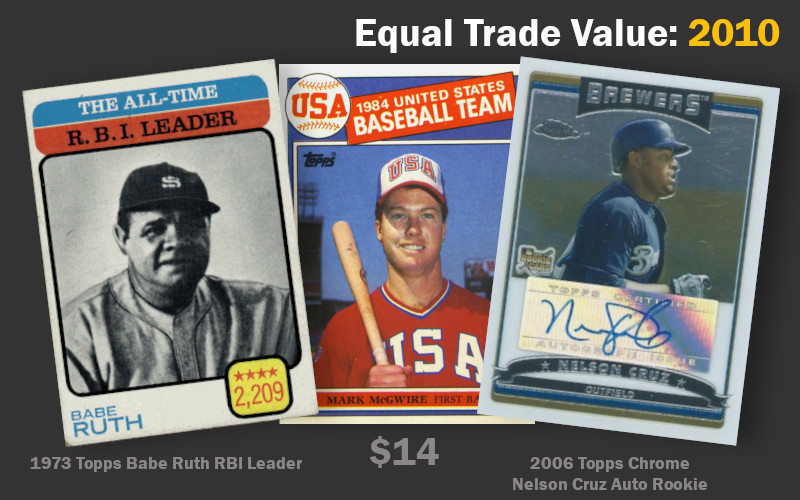

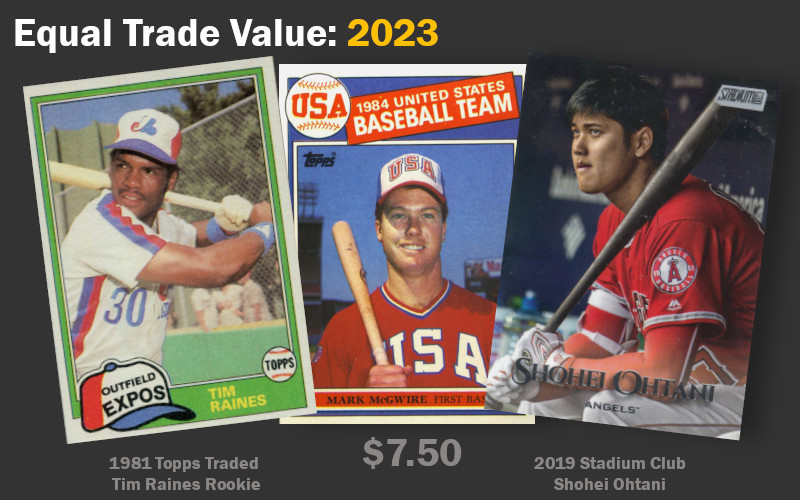

I have most of the Beckett magazines from the mid-1980s to the early 200s. I leafed through the year-end editions to look at the rise and fall of McGwire’s rookie card, noting a pair of cards at each point that carried equal trade value. The graphics below highlight a pair of cards that each have been considered of equal value to a McGwire rookie at some point. By the laws of the playground, any swap among these cards would have been completely fair. Although I never had a McGwire rookie until two years ago, I wonder if I would have every made any of these trades if they had been offered.

Traditional price guides have largely become irrelevant to collectors. To gauge current trade equilibrium, I looked at recent completed transactions on eBay and COMC and selected a pair of decent cards with multiple transactions taking place at identical price points to recent McGwire sales.

My Card After Spending a Year in My Pocket…