A few years I ago I came across a collector who carried around one of his favorite baseball cards in his wallet. The card was completely unprotected and emerged from his pocket after a year of abuse with creases and a lack of anything remotely resembling a corner. Given that the card in question was from the (relatively) modern 1990 Topps set, seeing all that damage made an otherwise uninteresting piece of cardboard extraordinarily interesting. I resolved to carry out the same actions with cards that I have always been drawn to.

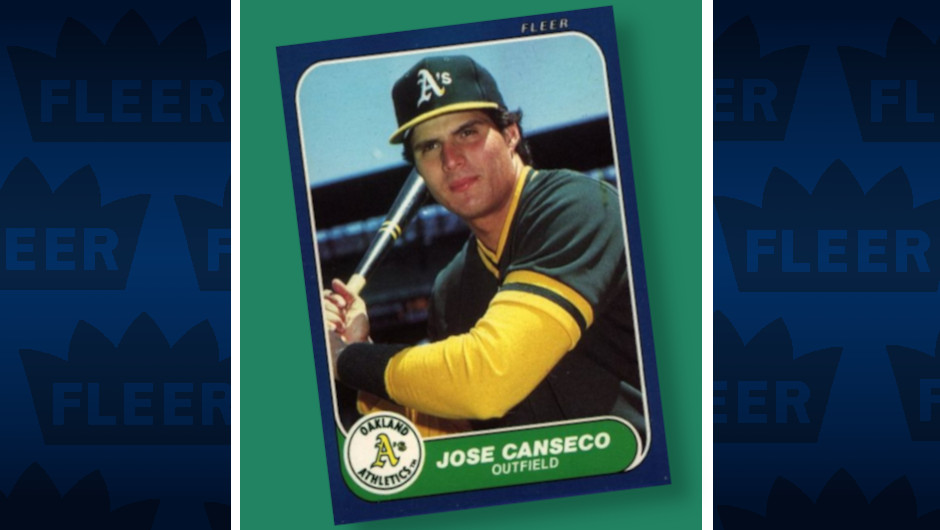

Each year on my birthday I select three cards that share a theme and place them in my wallet. They follow me around until another candle is added to my birthday cake, at which time they are replaced by a new trio. The first batch of wallet cards consisted of Jose Canseco rookie cards from each of the major card manufacturers of 1986. One of those rookies was made by Fleer, and everything I learned about the card is laid out below.

The Set: 1986 Fleer Update

As the inventor of bubble gum, the Fleer Corporation wasn’t eager to see the Topps Chewing Gum Corporation cut into its sales with baseball cards in the early 1950s. The Philadelphia-based company had already beaten Topps, Goudey, and Play Ball/Bowman to the market with a 120-card strip card set in 1923. Topps, however, acquired Bowman and engaged in legal maneuvers to lock up the commercial rights to most Major League players. Fleer tried to engage in the same tactics, capturing Ted Williams for the company’s 1959 and 1960 sets along with a selection of retired players. A set composed entirely of active players followed in 1963, but appears to have been cut short after legal pressure from Topps.

Faced with a tough legal battle, Fleer withdrew from the baseball card market to focus on candy and non-sports trading cards. The company kept a back-and-forth conversation going with the nascent MLB Players Association about the possibility of obtaining licenses to produce various collectibles. Talks broke down and the union made peace with Topps at the dawn of the 1970s. In 1974 Fleer explored the possibility of manufacturing cloth patches featuring active players but was rebuffed by the MLBPA on concerns that such a product would harm licensing revenue from Topps. Fleer sued and won a courtroom victory in 1980 allowing the firm to once again produce cards of active players.

Fleer and newly formed competitor Donruss rushed to obtain the proper licenses and produce cards for the 1981 season. The new cards were generally seen as being of poor quality with printing on poor cardstock, blurry photos, and numerous production errors. Topps continued to reign supreme in the eyes of collectors. However, a rising demand for baseball cards proved sufficient to carry the newcomers through the next few years. The two tier system of high demand Topps cards and lower demand Fleer/Donruss offerings persisted until the pair found their footing with collectors in 1984.

While Fleer’s 1981 set wasn’t seen as anything special at the time of its release, a single decision in setting up its checklist changed the course of baseball card collecting. Fleer included a card of a young Mexican pitcher who had appeared in a few late season games the prior year for the Los Angeles Dodgers. The card became the most popular of the year when the young Fernando Valenzuela went on one of the greatest pitching runs seen in a generation. It didn’t matter that Fleer had mispelled Valenzuela’s name on the front of the card. The only way to get a single player card of the rookie with a 2.48 ERA and nearly a strikeout per inning was to buy packs of Fleer cards.

Topps was not happy about this development and set to work to get its own Valenzuela card into production. The company had jammed Valenzuela into one of its ubiquitous multiplayer rookie cards in its 1981 offering, a style generally panned by most collectors. Fleer had simply produced a better card and Topps knew it. The solution was the creation of a new 132-card set that would be sold directly to hobby retailers. The number of cards in he set was calibrated to match the size of the cardboard blanks used in the printing process. Rookies that had previously appeared on multiplayer cards got their own solo cards, as did newcomers who had been overlooked when the regular season checklist was drafted. Topps recycled a mid-1970s idea by filling out the rest of the checklist with players who had been traded to new teams during the current season. These cards were marketed as the Topps “Traded” Series and were numbered on the back as a continuation of the regular 726 card set.

Topps made the new release an annual tradition, creating sets in 1982 and 1983. The ’83 set included the year’s only card of Darryl Strawberry, the next player to truly take the hobby by storm. Fleer and Donruss both missed the Mets’ rookie, a fact that combined with several years of lackluster products to reduce demand for their cards and prompted smaller print runs compared to the dominant Topps. However, lower production quantities, more attractive designs, and continued rising demand for baseball cards brought more interest to their offerings as the season progressed.

Fleer once again decided to take Topps head-on and released its own version of the Traded set. The company produced a 132-card boxed set comprised largely of rookies who had not appeared in the company’s regular season 660-card offering. The package did not give much of a name to the product, only identifying the box as containing as “logo stickers & updated baseball cards.” Some hobby publications referred to it simply as the “Fleer Extended Set.” It would take half a decade for the hobby to settle on Fleer Update as the proper name for the cards. Sales were lackluster with retailers initially reluctant to purchase in the required 100-set increments of dealer cases. Fleer eventually sold out the print run but had to warehouse a good number of the cards until reorders eventually depleted its stocks the following year.

Production Estimates

Despite the slow start, the set proved profitable and was repeated again in the following years. By the time 1986 rolled around collectors were warming up to the idea of not having to wait a year to see their favorite rookies and Donruss was preparing to introduce its first competing product. Like all baseball cards of the time, production quantities were much higher in 1986 than in 1984 and 1981.

No official production statistics were published for any of Fleer’s postseason sets but a rudimentary estimate of the number of cards printed can be constructed. Fleer produced several limited edition sets in the mid-1980s that have developed enough of a following to support the advertisement of a large number of key cards. The 1984 Fleer Update set contains the ever-popular rookie of Roger Clemens and the 1986 Fleer Update set includes a sought-after Barry Bonds. Bonds and Clemens share a similar hobby history and their careers ebbed and flowed at almost exactly the same rate. Both players are considered top-five all time players for their positions with arguments to be made for claiming the top spot. Both have had similar hobby receptions, complete with avid collectors and wider audiences trying to grapple with prickly public demeanors. The result is a fairly uniform demand for their cardboard that could lend itself to a direct comparison of the availability of these cards.

A review of the eBay listing history of these cards indicates there are consistently 5x as many 1986 Fleer Barry Bonds cards available at any time as there are 1984 Fleer Roger Clemens. Many Wikipedia-style collecting websites state 1984 Fleer production was only 10,000-12,000 sets, though this number seems low given the number of cards listed for sale and the fact that this would have only constituted just 100-120 dealer cases for the launch of a new product. Decades ago Tuff Stuff reported an estimate of 20,000 cards produced, though this again seems low for a new product (200 cases) in an industry that already had already surpassed a couple thousand hobby outlets. I unfortunately do not have access to how the publication arrived at that number other than the knowledge that it was just an estimate. With ~10,000 Clemens rookies slabbed by the major grading companies, the print run is likely at the upper bound of estimates that can approach 50,000 sets.

Using these figures as a building block, I estimate there were somewhere around 200,000-250,000 ’86 Fleer Update sets produced, and by extension, the same number of Canseco cards. The confidence interval around this number interval is very wide, but one can easily see that the number of cards produced is at least six digits.

The ’86 Fleer Update Canseco Card

Everyone loved Jose Canseco in 1986. Both the Baseball Writers Association and The Sporting News named him the American League Rookie of the Year. A teenage Joe Posnanski, the guy who would go on to write for Sports Illustrated and to author The Baseball 100, identified Canseco as one the up-and-coming left fielders to watch in a series of player-ranking articles published in Beckett Baseball Card Monthly (Parting quote: “It remains to be seen whether he will be a Mickey Mantle or a Ron Kittle”). Fleer was infatuated as well, producing at least a half dozen different cards and stickers that year featuring the Oakland outfielder.

Fleer put Canseco, who had only recently begun to show prowess, on a dual player card alongside Eric Plunk in the company’s regular 1986 set. In keeping with Update Series tradition, he was given a card of his own in the postseason boxed set. With the set’s checklist arranged in alphabetical order and bearing a prefix to differentiate from the regular versions found in wax packs, Canseco appears as card #U-20.

I’m pretty sure the photograph used on the card was taken by Ron Vesely. He had just become the primary photographer of the Chicago White Sox in 1985 and the upper deck of the stadium seen in the background looks vaguely like Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Other photos of Canseco apparently taken in the same photoshoot and available via Getty Images more clearly identify the setting as being Comiskey. Canseco is seen wearing the long sleeve version of the Athletics’ road uniform, further confirming this photo is not taken in Oakland.

The A’s visited Chicago three times from Canseco’s 1985 debut through the conclusion of the 1986 season. Two of these road trips (September 1985 and June 1986) took place early enough in the season to allow the card’s artwork to be laid out ahead of the ’86 Fleer Update set going into production. He is shown wearing a long sleeve jersey, something that could be expected on either date given historical weather data showing Chicago had low gameday temperatures of 49 and 54 degrees during these visits. Temperatures warmed up considerably for all but one of the games played on these road trips with only the September 21, 1985 event barely getting past 60 degrees. Canseco’s haircut resembles the style seen on his 1985 and earlier minor league cards while most of his 1986 and later issues show a closer cut, making it more likely that the photo shoot took place in September 1985. Given the weather conditions, Canseco’s attire and haircut, the photo was most likely taken on September 21, 1985. This might be the oldest photo used on any of his 1986 rookie cards.

While the front of 1986 Fleer cards often suffer from chipping, it is the back of the cards where one actually has the hardest time finding truly mint condition examples. The black borders at the top and bottom lack the protective layer of gloss that is present on the front and are usually encountered with some degree of wear shining brightly as white specks against a dark background.

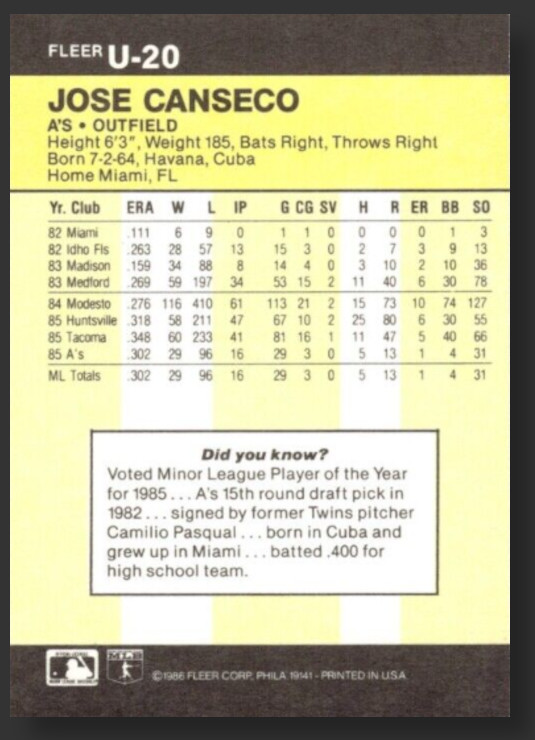

Below the black bar at the top of the card are the standard demographic datapoints familiar to baseball card collectors. Canseco would go on to become infamous for his nutritional regimen, a fact amplified by this card reporting that he weighed 185 pounds. Five years later his Topps baseball cards reported a weight of 240 pounds, implying a gain of 55 pounds in a rather compressed timeframe.

Canseco’s card is one of six in the set that have an error printed on the back. While most errors in the set had a misspelled name or an incorrect stat line, this particular card has something a bit more confusing. The card clearly shows his batting statistics but the headers above each column refer to pitching statistics. The result is a career .302 batting average being reported as a .302 ERA, his 16 runs scored appear as 16 innings pitched, and 5 home runs are written as 5 hits against him. Amazingly his 31 strikeouts match up with the strikeout column. No corrected versions were ever produced, making this just a bit of a novelty rather than a rarity to be chased by collectors.

Hobby Reception

Like earlier editions, the ’86 Fleer Update set found some uptake but took a couple years to really gain acceptance within the hobby. Canseco won the American League Rookie of the Year Award that season, but interest in his card was no greater than some of the other prospective stars at the time of the cards’ introduction. The rookie card of Wally Joyner, who had 19 home runs at the All-Star break, was the most sought after card inside cartons of ’86 Fleer Update and wouldn’t give up that relative position until Canseco’s 40/40 season in 1988.

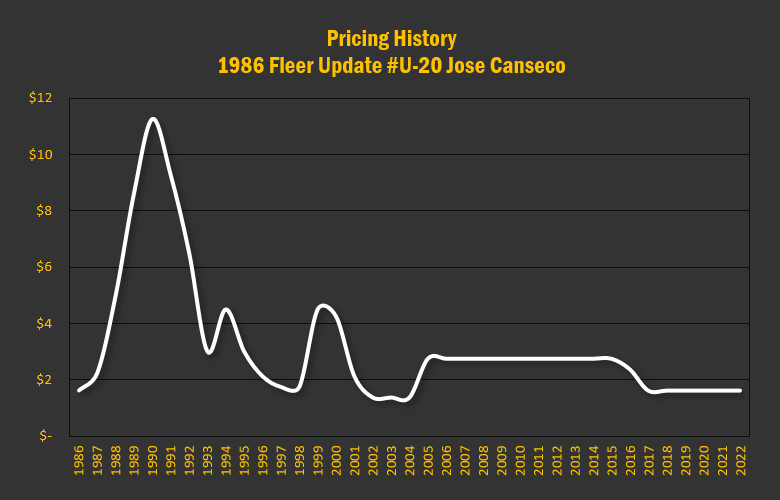

The extended/update sets produced at the end of the year by card manufacturers traditionally provided an affordable way to get cards of the season’s top rookies. Previous years that saw players appear in both the regular flagship and update sets typically produced lower prices for the end of year versions. ’86 Fleer Update was not an exception with its singular posed Canseco card lagging the dual rookie Eric Plunk/Canseco version available in regular packs of ’86 Fleer. The cards were first reflected in the November/December edition of Beckett Baseball Card Monthly with a quoted range of $1.00-$2.25, roughly the same as what you can expect to lay out for an ungraded copy today.

Based on data reported in price guides of the era, demand for the ’86 Fleer Update Canseco peaked in 1990 and began a volatile decline through the 1990s. I searched for the highest price ever paid for one of these cards and found an erroneous report of a NM-MT example selling for $1,902 in a 2008 Memory Lane Auction. Further research of the sale date and lot number indicate PSA’s data collection system confused this card with a much rarer card of King Kelly from 1887. The actual highest sale price of this card appears to be a $250 transaction that took place March 2021 involving a PSA Gem Mint 10 example.

Trade Bait

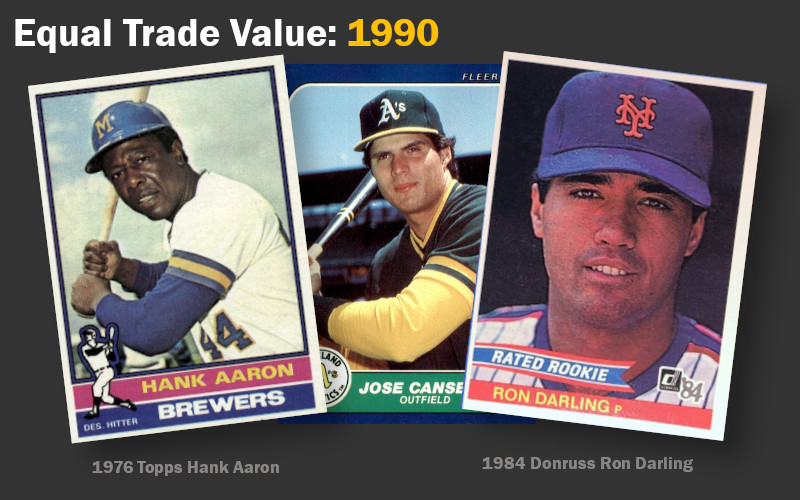

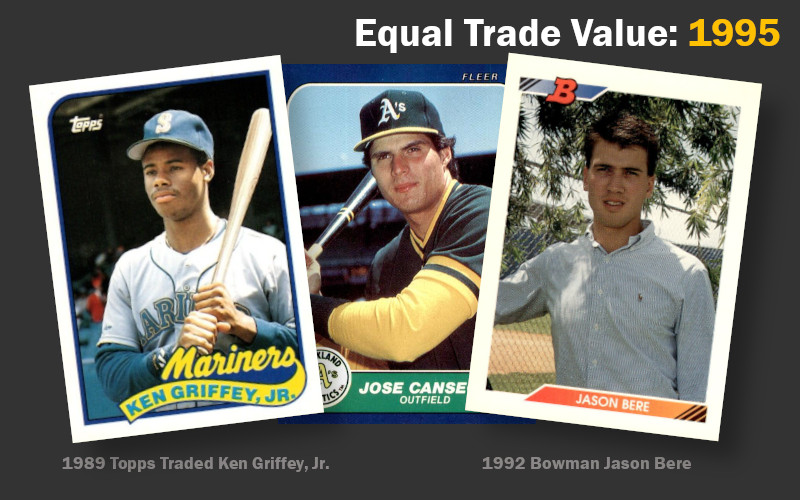

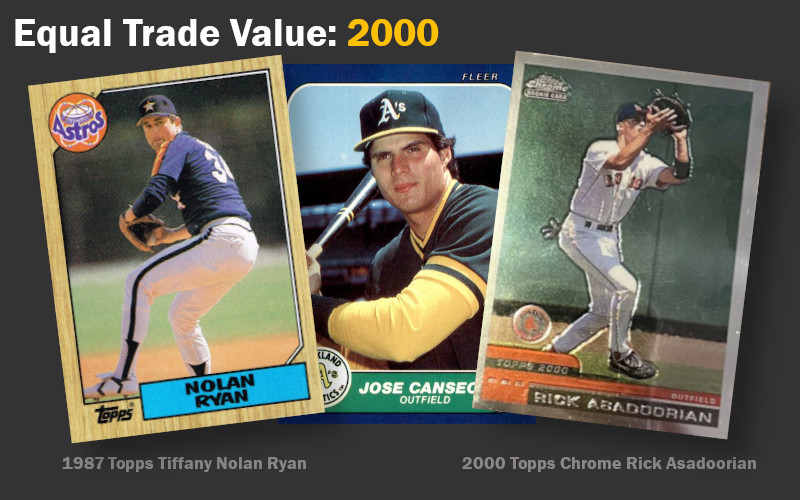

As a kid, my friends and I would sit on the steps of our homes and trade baseball cards. We all had our favorite players, but baseball cards were serious business and preferences for specific names and teams took a backseat to whatever Beckett Baseball Card Monthly‘s price guide said they should be valued at. The ironclad rule at school and my neighborhood was that any trades had to be of equal value as determined in the latest price guide. Even if you wanted to trade your $2 Ken Griffey, Jr. card for a $0.75 Cecil Fielder the other kids present would immediately force your trading partner to pony up another $1.25 worth of cards.

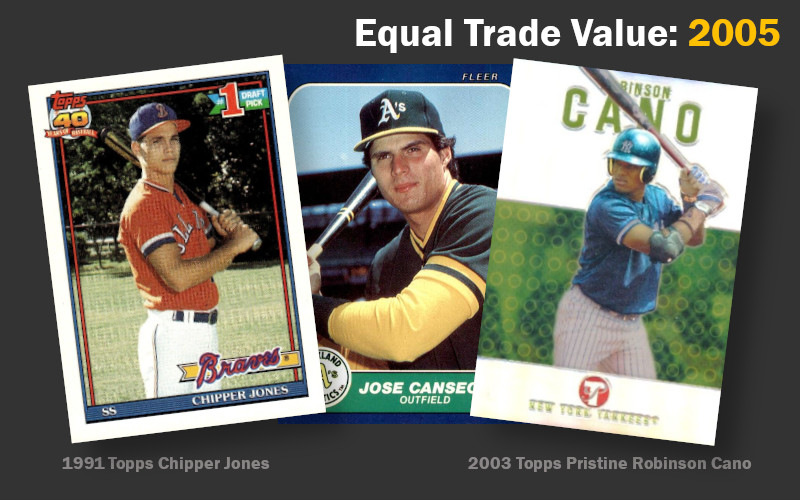

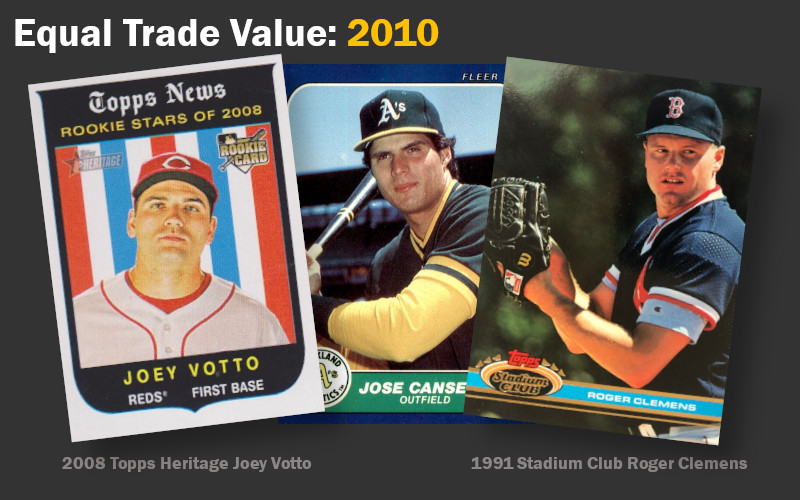

I have a nearly full run of Beckett magazines stretching back nearly 30 years. Looking at that pile, I find myself referencing random cards and imagining what kind of trades would have been seen as completely fair at various points in time. So what would I have had to theoretically give up to get this card in the past? What could I have then swapped it for in the future?

What follows are a pair of potential trades at several different points. Some would have been absolute steals and others huge disappointments. The constant in each potential swap is that all cards were valued equally at the time in question. These were completely fair trades. Black Jack, No Trade Backs.

My Card After a Year in My Wallet: