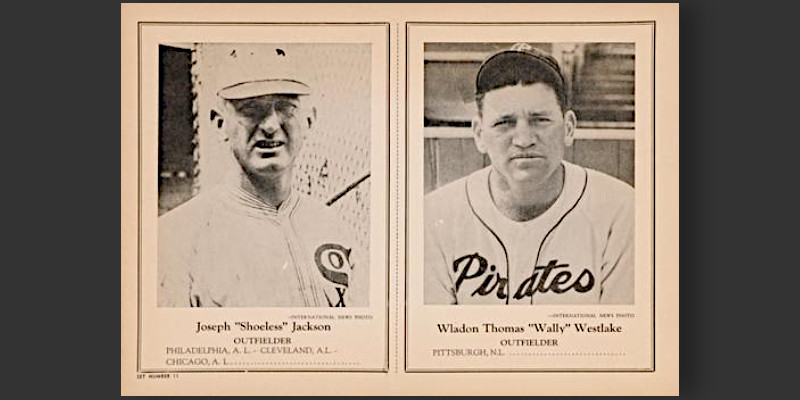

For a guy who made his debut at age 26 and struggled to get full playing time after turning 30, Wally Westlake sure has some interesting baseball cards. Card collectors and Immaculate Grid players alike should take note of this name. How many other players can claim to share their rookie card with Shoeless Joe Jackson?

Westlake broke into the big leagues in 1947, a period in which large format photos masquerading as baseball cards were distributed to subscribers of The Trading Post, an early hobby publication. These “cards” were referred to as the Sports Exchange and are classified in hobby catalogs as strip cards with the designation W603 as some were intended to be cut into individual panels.

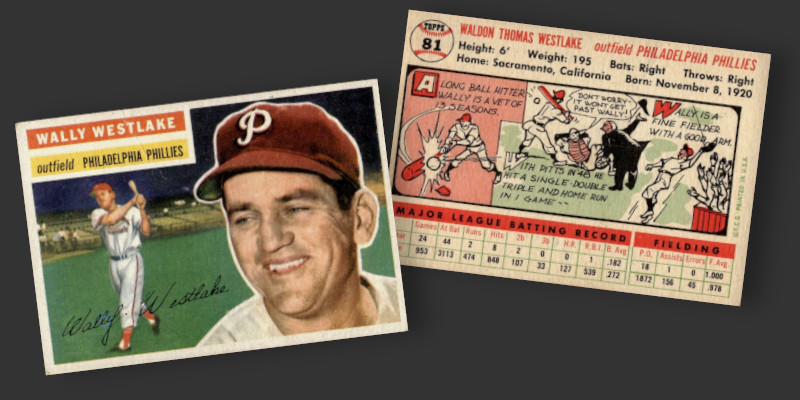

Westlake bookended his cardboard career with another oddity. He appears in the 1956 Topps set as an outfielder for the Philadelphia Phillies. Now with the sixth team in five years, Westlake had been signed in the 1955-56 offseason to provide some pop at the plate alongside a serviceable outfield glove. Indeed, the comic strip on the back begins by calling out him as a long ball hitter and ends by highlighting his good arm. Too bad he played all of five plate appearances across five games before being released one month into the season.

Wally’s brother Jim actually appeared as well with the Phillies for a single plate appearance that season. However, it was the more established brother that was able to add another card to his cardboard checklist.

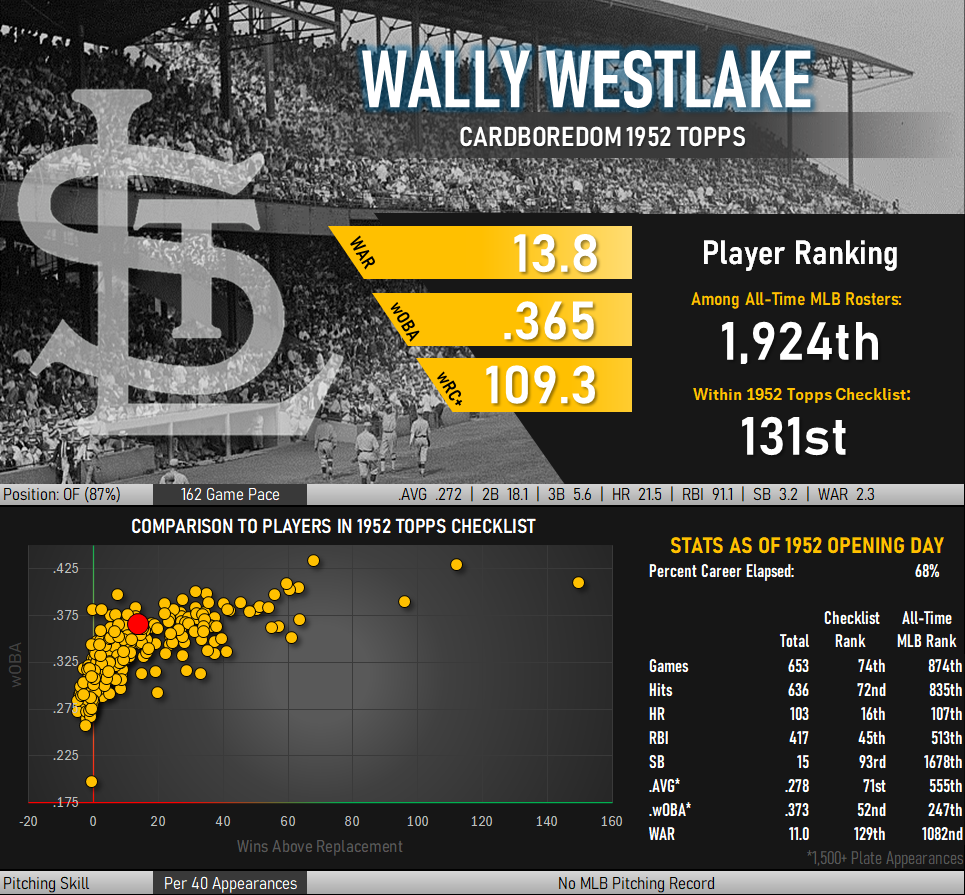

Wally Westlake’s cards, excepting the one he shares with Shoeless Joe, are generally considered to be equal to that of any other common journeyman utility player. That’s selling him a bit short, as the stats on the back of his cards are just as interesting as the cards themselves. Topps wasn’t lying when their cartoonist called Westlake a long ball hitter. He averaged more than 20 home runs per 162 games over the course of his career, even with a drop off in production after age 30. Considering that he didn’t make his MLB debut until age 26, one can imagine a much more memorable stat line if given more consistent playing time and a more traditional starting age.

Interestingly enough, there are some oddities to play around with the stats that he did manage to accumulate. Westlake was not the best baserunner, as evidenced by his stealing only 19 bases across 49 career attempts. However, this was a guy who hit for the cycle twice and averaged almost a half dozen triples per 162 games across the entirety of his big league career. Let’s not forget how sure handed he could be, as Westlake finished his career among the top 10 outfielders in terms of fielding percentage.

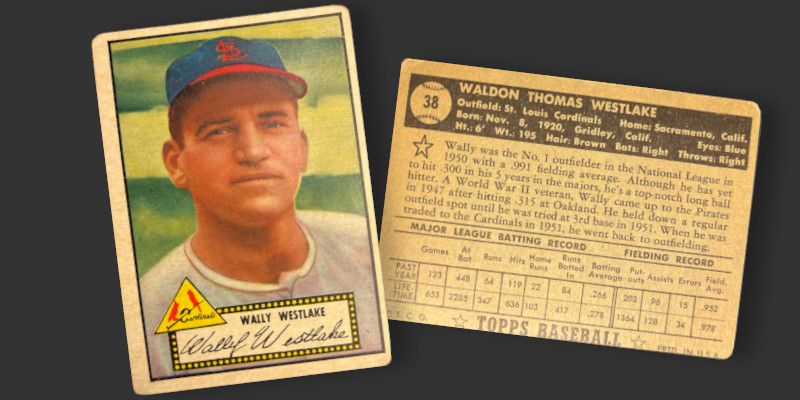

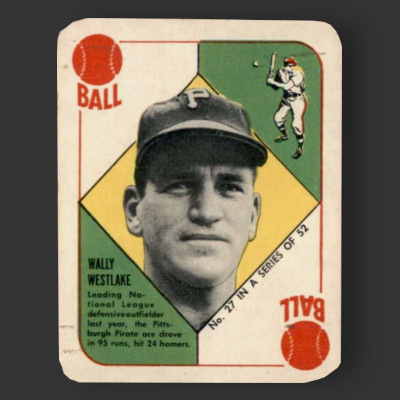

All those team changes were tough to keep up with. Topps got its first taste of rapid fire editing when Westlake was traded from the Pirates to the Cardinals at the 1951 trade deadline. The bubble gum maker recycled the prior year’s photo for Westlake’s 1952 card, but managed to paint a St. Louis cap over his Pirates headgear. Take a closer look at the gold piping around the collar of his jersey and it becomes quite apparent that this is a Pittsburgh-era photo.

Westlake had just come off a decent season in his mixed Pirates/Cardinals season, hitting .266 with 22 home runs and 84 RBIs, so it is not hard to see why other teams would want his bat in the lineup. Not sourcing a new photo worked out for Topps, as Westlake had been traded again to the Reds shortly after this card went to press. By the time kids were opening sixth series packs he had been dealt yet again, this time to the Cleveland Indians.