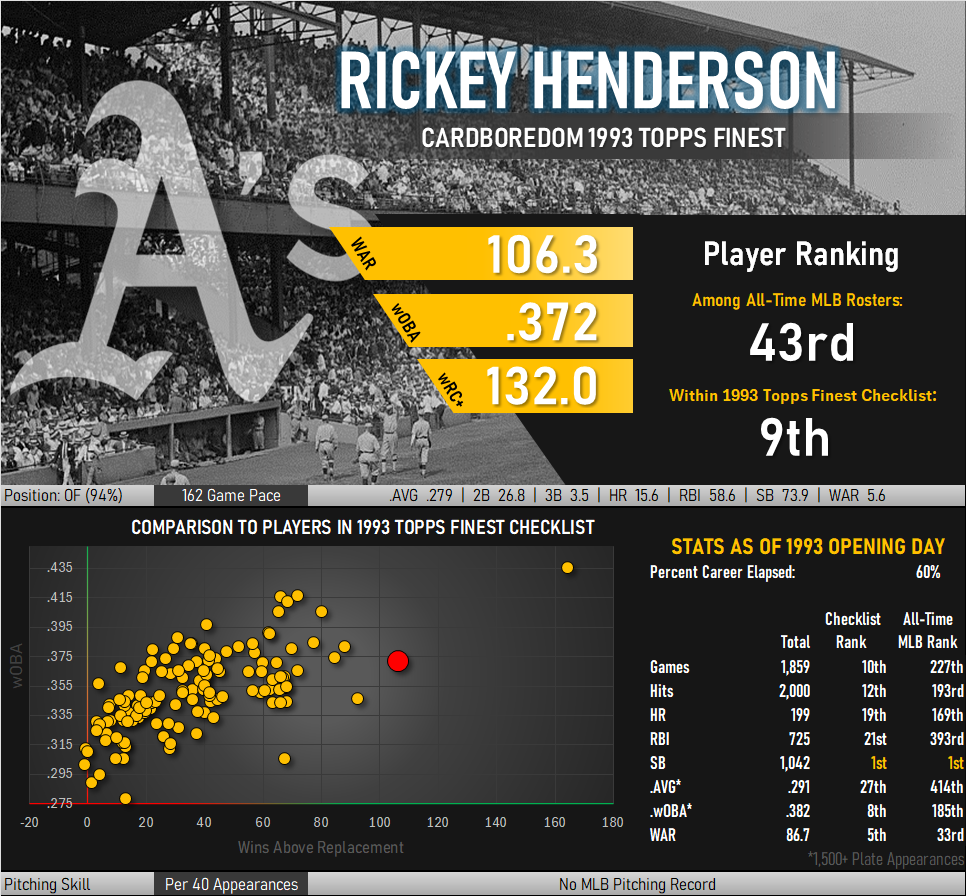

Rickey Henderson is one of the most unique players of all time, joining a very small handful of guys you really can’t a good comparison for. Baseball Reference calculates a Similarity Score for every MLB profile on its site. This score is based on a back-of-the-envelope scoring system previously introduced by Bill James and slightly modified by the BR staff. The rubric assigns a score of 0-1,000 for every other player who appeared in an MLB game with higher scores indicating similar performance over the course of a career.

Most players have a counterpart with a score well above 900, though there are few with a distinct lack of comparable athletes. These ballplayers are truly in a league of their own. Pete Rose is the most unique by this measure, having the career of Paul Molitor as the most similar (score 686) and only three other players even breaking the 600 barrier. Josh Gibson, the catcher with a .373 career batting average and either 166 or 800+ home runs depending on your source, likewise has few players able to even stand near his statistical shadow. At least a dozen players score above 600 against Gibson, but nobody is able to get any closer than 686 points.

Rickey Henderson joins these luminaries in terms of having few peers, and in true Rickey style he manages to do so in a really odd way. Craig Biggio and Johnny Damon are able to nudge just past the 700-point mark in terms of similarity. Paul Molitor even repeats with a 686-point showing, the same similarity he displayed with Pete Rose.

Here’s where it gets really interesting. Baseball Reference not only calculates a score for a player’s career, but provides a separate ranking for each age in which a player took the field. You can look up Rickey Henderson’s age 21 season and find Rick Manning (score 972) to be the 21 year old who posted the most similar numbers across baseball history. You can look up Rickey’s age 24 season and see Tim Raines leading the pack with a score of 945. Raines repeats as the most similar at age 25 (941). And age 26 (928). And more. Raines is year by year the closest thing to a Rickey Henderson clone every single year through age 39. He even comes back to nab top honors at age 42. Despite almost two decades worth of almost being Rickey, Raines ranks 9th in career similarity.

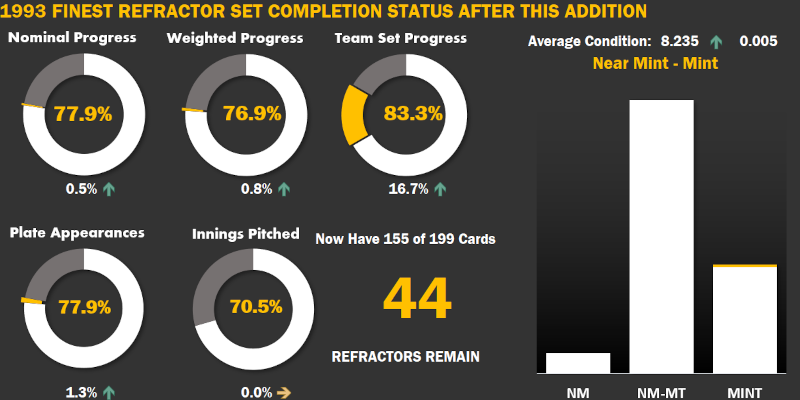

Look at the chart above. The red dot representing Rickey is pulling away from the rest of the pack with only Barry Bonds registering as having a more productive career. Look further down to where I calculate that Rickey stole 74 bases for every 162 games in which he appeared. Ronald Acuna went crazy on the basepaths this season, swiping 73 bags in 159 games (pace: 74 per 162 games). Rickey averaged Acuna’s breakneck pace over a 25 year career.

Looking For the Perfect Way to Summarize Rickey in One Stat

This is a ballplayer whose career lends itself to a list of one amazing statistic after another. He is the all time leader in runs, arguably the fundamental bedrock of baseball offense. He did this as a right-handed hitter, something that becomes more eye opening when it is realized that 4 of the next 5 runners up were either switch hitters or batted left-handed, giving them two extra strides on the basepaths.

He is neck and (bigger) neck with Barry Bonds in terms of career walks, though Rickey’s performance may be more impressive. Bonds’ walk totals soared to ludicrous heights when he took aim at the single season home run total, drawing walks of the intentional variety in 27% of his free passes. Pitchers wanted Bonds on base to limit potential damage to their win-loss records. Rickey, on the other hand, walked almost as much but was a nightmare on the basepaths. Walking Rickey was the last thing pitchers wanted to do and they showed it by issuing intentional walks in only 3% of these encounters.

In the end, it is going to be something related to stolen bases that ends up being my “go-to” stat. It won’t be his habit of telling defensive players about his plans for stealing bases and then carrying out the feat. It won’t be his holding the modern record for both single season and career stolen bags. It isn’t the fact he once stole 33 bases in a single month (enough to lead the entire 2021 National League season) and was only thrown out once. It’s not even that he is the all-time SB leader among Yankees players despite playing only four seasons with New York.

The most impressive stolen base feat is his proclivity for stealing third base. Stealing third is hard. Getting to second base in order to even be in a position to consider taking third is challenging. Rickey had a .401 career on-base percentage, augmented by more than 3,000 hits and the second highest number of walks in the history of the game. He put himself on second with more than 500 doubles. Rickey was in position to take third often.

The runner is directly in the catcher’s field of vision throughout the play, making it difficult to catch the defense off guard. Once the catcher has the ball in hand, it is only a short distance of 90 feet from home plate to the waiting third baseman’s glove versus 127 feet from home to second. A ball traveling at a constant speed takes 41% more time to travel 127 feet as opposed to 90. The best catchers throw the ball to second at speeds reaching the upper 80s mph. The shorter distance to third effectively makes stealing third akin to taking second against a catcher who can chuck the ball towards the bag at 120 mph. MLB StatCast is now tracking catcher’s pop times, a measure of how quickly they receive a pitch and relay the ball to a waiting position player. Catchers get the ball to third base about a half second faster than to second.

Baserunners sometimes report stealing third is easier than second because pitchers assume their defensive advantages will negate aggressive baserunning. Sometimes this lulls them into slower deliveries, believing the runner won’t take off. No pitcher was ever calm when Rickey was on base. Pitchers were always switching to their quick release windups whenever he was around.

Facing these impediments, only the fastest and most daring are going to take third base successfully. Just a dozen players have managed to swipe third at least 100 times in the careers since WW2. Most of these names barely crest triple digits. Among the leaders are Vince Coleman (2nd place, 189 steals) and Juan Pierre (3rd place, 133 steals). Rickey stole third 322 times, as much as second and third place combined.

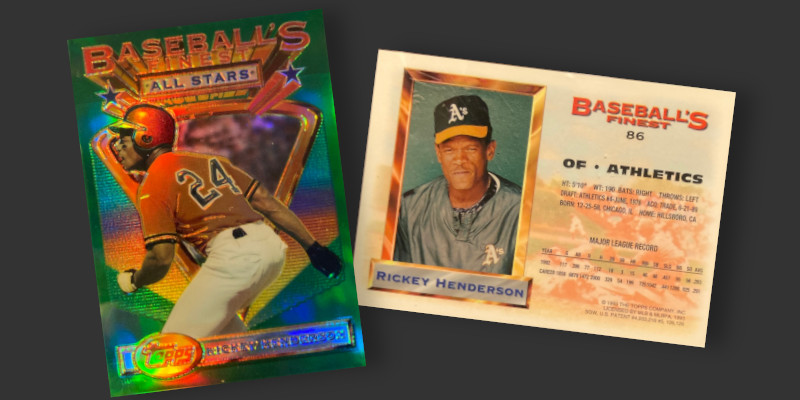

The Shiny Rickey Henderson Card in 1993 Finest

It seemingly took forever to locate a copy the Rickey Henderson card for my 1993 Finest Refractor collection. Several came and went while I was looking, but the cards would seemingly be sold before I even knew they had been listed for sale. There is an extremely active player collector community chasing Rickey’s cards and you have to be quick to find land one.

After two years of looking I eventually found a NM-MT example and added it to the collection. Amazingly, a mint copy appeared three weeks later as another collector began to liquidate a set that was more than 90% complete. I upgraded my card and quickly moved the earlier version to a fellow set builder who had yet to come across an available card.

Rickey played for nine different teams in his 25 year career. The Oakland native played more than half this time with the Athletics. This card depicts him in his second stint with the team, wearing one of the club’s distinctive yellow Spring Training jerseys. This card would have looked strange with any other team.