From time to time I have written about the interns I see at work. Our latest recruit starts her summer term with us this week and I have high hopes given the enthusiasm she showed during the interview process. I regularly sit on interview panels and am usually called upon to set a practical problem in front of candidates to see how they approach it.

My industry is famous for brain teasers, such as when I interviewed and was asked to calculate Russian Roulette odds on the fly while recommending optimal strategies as assorted rule changes and optionality were added. I try to keep my own problem sets a bit more grounded in reality but like to see who has that spark of reasoning.

I presented one of my prior candidate pools with a financial model and asked them to identify items that stood out as red flags, following up with what line of questioning they would pursue to resolve their concerns. Many figures were intertwined so that changes in one column affected other ratios and totals in a cascading effect throughout the document. The key to unlocking the model was to realize that an average value encountered early in the process would be implausible given the numbers on a table above it. To notice this the candidate would need to be observant and quick with mental arithmetic.

A predilection for devouring numbers and rearranging them in various what-if scenarios seems to be a common theme among long-time baseball fans. The game generates an endless stream of data year after year, and us card collectors spend our time amassing stacks of cardboard with those little numbers printed on the back. Last summer I particularly enjoyed reading one of these discussions about miscalculated statistics across much of the 1953 Bowman Color and B&W checklists.

While I can solve just about any problem in front of me and can recite the Pythagorean Theorem all day long, I am not well acquainted with the actual names underpinning pretty much everything else in a math textbook. Asked to walk someone through my work, my explanations tend to devolve into a series of “…move this number over here, put this one there, that line cancels out the other one, carry the four…”

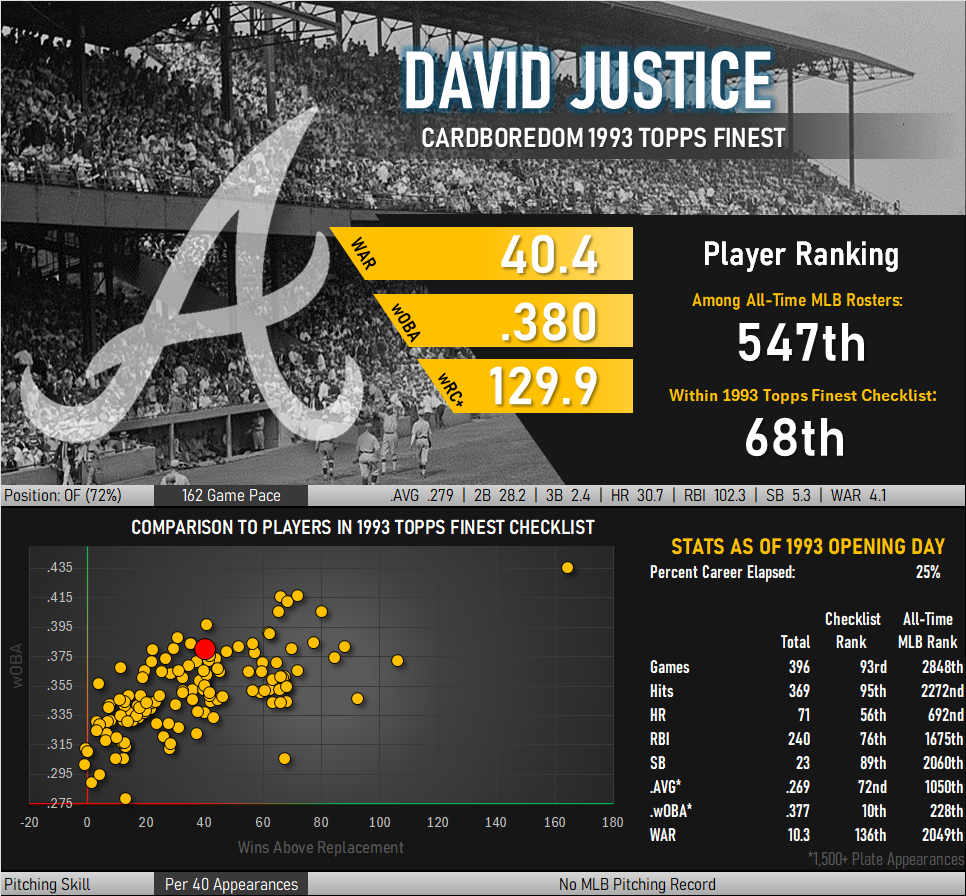

Imagine my surprise when I began typing into a search box to see if there were any odd facts about David Justice, the next name added to my set building project, and discovering something that reminded me of some of Bowman’s statistical missteps.

Recurring throughout the search results were references to Simpson’s Paradox, which describes a scenario in which multiple datapoints independently point to one result while an overview of the data in the aggregate leads to an opposite conclusion. The most frequently cited example of this, at least when search terms include Justice’s name, shows the paradox at play in a comparison of the batting averages of Justice and Derek Jeter. Looking at their comparative performance in 1995 and 1996, it appears that Justice consistently outperformed the New York shortstop by an average of 5 batting points annually.

| Player Name | 1995 | 1996 |

|---|---|---|

| Justice | .253 | .321 |

| Jeter | .250 | .314 |

All batting averages are not created equal. Sample size matters. Look at what happens when averages are calculated for the combined 1995-96 period:

| Name | 1995 | 1996 | Combined | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Justice | 104 for 411 | 45 for 140 | 149 for 551 | .270 |

| Jeter | 12 for 48 | 183 for 583 | 195 for 630 | .310 |

When viewed on a composite basis it becomes clear that Jeter outhit Justice by 40 points!

I get the impression that Justice would have geeked out a bit over this kind of thing. By all accounts he did well academically. He is an alumnus of the Covington Latin School, which assigns students to their respective grade levels based on test scores rather than age. Transferring to the school at the conclusion of sixth grade, Justice immediately skipped seventh and eighth grades.

The comparison of Justice and Jeter isn’t as random of it may seem. Both were Rookie of the Year winners and both were staples of the postseason. The pair are in the all time Top 10 for playoff/World Series games, at-bats, runs, and RBIs. Jeter’s extracurricular run all came with a resurgent Yankees dynasty in which he amassed more postseason appearances (158) than any other player in history. Justice got his first taste of postseason play with the 1991 Atlanta Braves before becoming something of a journeyman and proceeded to participate in all but one postseason series for the rest of his career. Today he still ranks third (ahead of Jeter) in career postseason RBIs.

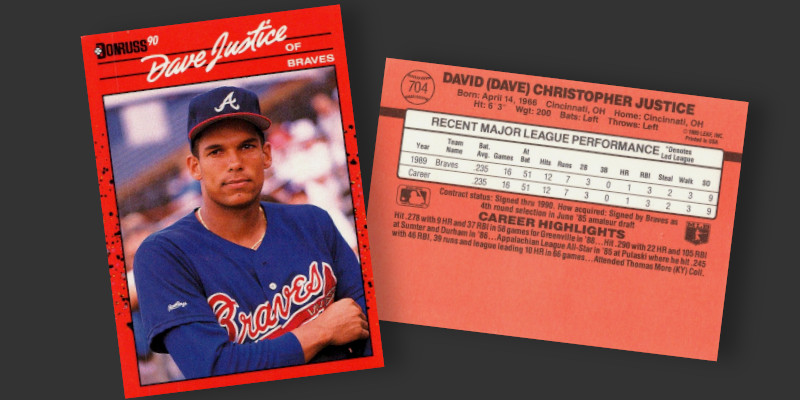

His appeal wasn’t rooted in his postseason heroics, but rather in the steady excellence of his regular-season performance. Year after year, he remained a reliable power hitter, consistently threatening the 30-home-run, 100-RBI mark—just like many of the players I admired most. Over time, his stats began to mirror the old timers that dotted my vintage cards, such as Gil Hodges and Frank Howard, further cementing his place among my favorites of the 1990s. His 1990 Donruss rookie card always held a prime spot in my collection, with multiple copies either protected in top-loaders or positioned at the center of a 9-card page in the “good cards” binder. The fact that we share the same first name doesn’t hurt either.

Within a few years cards featuring Justice fell to minor star status, though his cards never stopped being added to my binder. Until recently, my lifetime accumulation of Justice cards was limited to base issues from Donruss and other non-premium brands.

I didn’t see much in the way of SPx or Finest and am apparently not the only one in this position. Justice’s ’93 Finest Refractor is one of the tougher names to find in the set, having publicly changed hands just 16 times over the past three years and showing similar levels of transactional scarcity for the better part of two decades. Amplifying this effect are the presence of a couple of extremely dedicated player collectors and at least one Refractor fan sitting on multiple examples of the card.

These are not the only reasons for poor availability, as a quirk of the production process helped set the stage for limited offerings of the card. More will be written on this subject later when I expand on a theory that has been building throughout my set collecting effort.

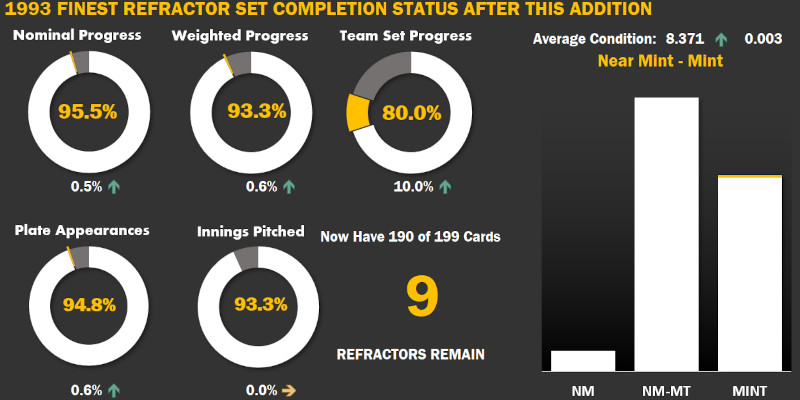

It’s a tough card, and one that caused some fits for me when trying to acquire a copy. The one I purchased was sourced from the set break that provided so many of the cards recently profiled here. However, I wasn’t the one that purchased it out of the set. More than one collector was vying for the cards at the same time. Another buyer stepped up for the Justice refractor while I was busy securing Barry Bonds and Randy Johnson for my checklist. Shortly after the dust settled, the new Justice owner offered me the card at a sizable markup. Just 10 cards away from completing the set and facing a particularly tough name that goes months without being seen (at any price), the offer was accepted. So far it’s been worth it.