The 1940s may have been one of the loudest in human history. The decade began with the brassy sounds of big bands booming out of suddenly ubiquitous radios. The tone of this music was shifting from Depression Era notes to higher tempo swing. Baseball cards were flipped on playgrounds across the country, with seemingly everyone tuning in for the latest updates on Joe DiMaggio’s hitting streak or the crack of Ted Williams’ bat towards a .406 batting average.

Things were about to get much, much louder. Shortly after that 1941 baseball season concluded, America woke up to the sounds of airborne torpedo bombers, deafening explosions, and a chorus of more than 2,000 bugles calling Taps. Joining the sounds were declarations of war, the call of whistles mobilizing millions of soldiers, and the whoosh of pressurized steam setting every bit of available machinery into motion. Within four years, the time it takes to get through high school, the loudest sound of the war would be unleashed in the form of a pair of city-erasing nuclear blasts.

Amid the loudest decade in human existence was something else: An absence. This was a world in which availability of items previously taken for granted plummeted to zero, the government legally commandeered production of almost every aspect of American life, and all of this was happening without any guarantee that the people surrounding your life would even make it out alive. All of this played out in one of the simplest parts of early 20th Century American childhood, the humble baseball card. These little pieces of Americana just vanished for a 7-year span from 1942 to 1947.

This period in card collecting is known as the Wartime Gap, a name that seems pretty self explanatory. Baseball cards were eliminated from store shelves in 1942, but things hadn’t really stopped. Baseball was still being played, Ted Williams won the American League Triple Crown, the Great Depression was over and kids had nickels to spend. So why did an entire generation of children just completely miss out on cards?

Antebellum Cardboard

Through this point the 1930s had been one of the most prolific periods of baseball card production, yet there is no way an observer would classify their production as their own standalone industry. They were a bonus sold on an ancillary basis within the broader candy business.

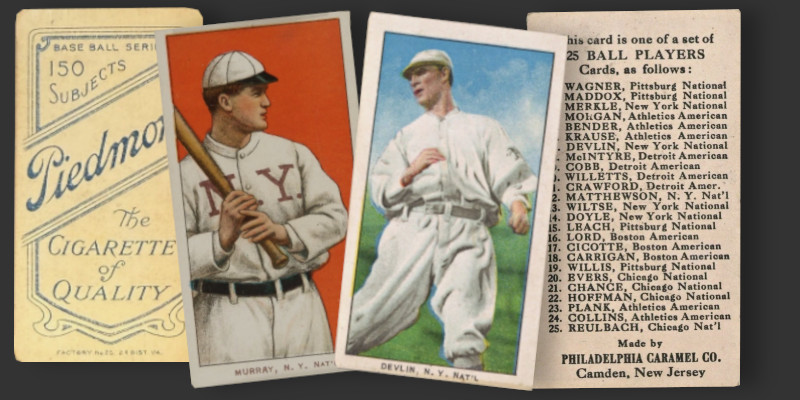

Baseball cards had begun life in the late 19th-century as a way to liven up the cardboard stiffeners found in packages of tobacco products. Their use as a packaging element continued after the turn of the century, expanding to include the sale of various soft candies such as those sold by the Philadelphia Caramel Company.

Despite some expansion into portions of the confectionary business, tobacco dominated the distribution of baseball cards for the early portion of the 20th century. The 1920s brought with it a significant rise in the popularity of chewing gum due to advancements in manufacturing, which allowed for greater variety and faster production. Combined with evolving cultural shifts, gum became associated with energy and youth. Soft, pliable gum sold to young people became the perfect distribution medium for stiff pieces of cardboard bearing the images of their favorite sport, establishing the core business model for the 1930s.

Kids were primarily buying these waxy paper packages for the piece of gum inside. The card, as an effective marketing gimmick, was an exciting collectible bonus that drove brand loyalty and repeat purchases. Gum drove the initial purchase, and the pennies kept flowing to the candy makers through customers’ desire to acquire the next card to finish the checklist. Card manufacturers were gum makers first and printing companies second.

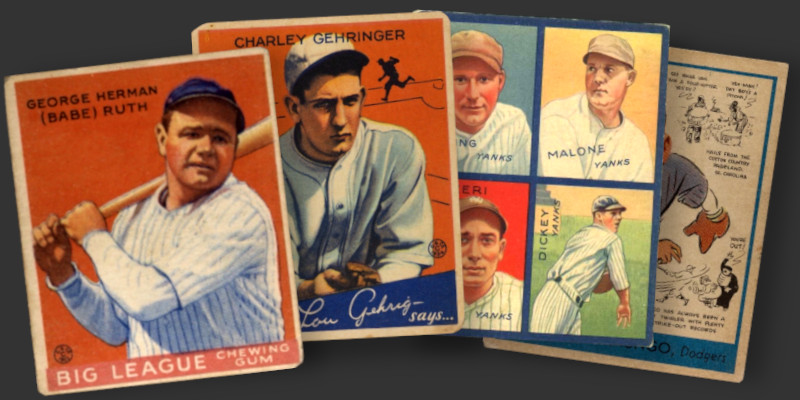

The market for these gum cards exploded in the 1930s. The Goudey Gum Company made a concerted push to market its penny gum through the issuance of a massive 240-card set of cards. This issue really set the blueprint for what a comprehensive, highly collectible set should be. Vibrant colors were used to reproduce artwork based on early baseball photography to create a truly cohesive, attractive product.

Selling discretionary consumer goods into the teeth of the Great Depression was a tall order, no matter how good the baseball cards were that were being thrown in for free. Goudey found itself struggling for survival and competitor National Chicle went bankrupt at the outset of 1937. The industry was aggressively innovating to get kids’ attention and redirect it (and their pennies) towards the ultimate product, gum, and these firms were bleeding market share to a Philadelphia upstart with a name matching its maniacal obsession: Gum, Inc.

Depression era pricing (three pieces for a penny) earned the business a 60% market share, and its management set its sights on capturing the remaining 40% through the issuance of baseball cards under the Play Ball brand name. By 1941 there was market leading Play Ball realism, extremely bright colors from a diminished Goudey, and a lower quality multiplayer issue from Gum Products, a firm trying to reclaim National Chicle’s former position in Boston. The ’41 Play Ball set captured Joe DiMaggio in the midst of his 56-game hitting streak and Ted Williams hitting .406. It was the final high water mark, the last great pre-war set. DiMaggio’s Yankees defeated the Dodgers for the ’41 World Series title and manufacturers set to work getting ready for the next round of baseball card releases.

Flipping a Switch

Gum and baseball cards had been intrinsically linked for 8 years. The cards of the 1930s and early 1940s hold a special place in collectors’ hearts, not because they were intrinsically such good cards, but because they represented a different era. There was no gradual evolution from “old” to “modern” cards – it was a step change as discrete as the flipping of a light switch. That switch, which transitioned us from a world of big bands and bright lights to one of curfews and blackout curtains, flipped on the dawn of December 7th, 1941 and would keep gum and cards apart for almost as long as they had been together.

The effect was immediate. Bob Feller, one of the biggest names in baseball, told his team that very afternoon of his intentions to enlist in the Navy. 48 hours later he was on his way with thousands of volunteers for training in Norfolk, Virginia. Mobilization of the nation’s industrial base kicked into high gear, upending any sense of normalcy as capital stock was rapidly reconfigured for wartime manufacturing. For non-essential goods like baseball cards, this meant an instant shutdown of production. The government did not ask nicely, it legally commandeered raw materials through agencies like the War Production Board and the Office of Price Administration.

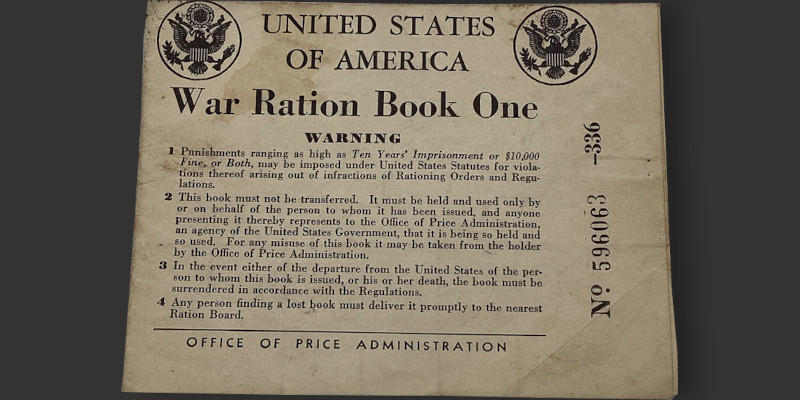

Every single production decision was rooted in military necessity and, when needed, decisions had to be made as to who would get allocated access to various commodities. That started with sugar, the most basic component of candy production. Sugar wasn’t just used for the sweets we think of today. It saw heavy use in everyday baking and extending the shelf lives of canned goods. It’s stabilization properties and ability to be further processed into various low cost alcohols made it a perfect material from which to produce large quantities of explosives, properties that were suddenly in very high demand. Shipments from the Philippines, one of our primary sources, had been declining for years with the imposition of import quotas and were essentially cut off when Japan invaded the islands just 24 hours after hitting the US Pacific Fleet in Oahu. The rapidly growing threat to shipping in the Caribbean and need to divert ships to carrying war materiel further reduced access, as did crop failures in Puerto Rico. As a result, it was sugar, rather than gasoline, nylon, or rubber that was the subject of the OPA’s first ration books issued in April 1942.

Sugar was too valuable to waste on frivolities. The ration book became a profound part of the American homefront experience, institutionalizing scarcity. Every family had to register for their books and accompanying time-limited stamps, usually at a local elementary school. Buying sugar required having funds for the purchase as well as the specific stamp entitling that specific individual the right to their allotment. This allocation was initially about a pound per week, though this was further reduced when advancing Allied lines expanded the portion of the map needing access to the goods transiting American supply lines.

This completely choked the confectionary industry, which saw their allocations cut to 70% of pre-war access. Recipes were adjusted, product lines modified, and molasses and corn syrup employed to bridge the gap, but nothing could replicate the texture and sweetness needed for palatable, mass-produced gum. No cane sugar simply meant no gum, but this wasn’t the only roadblock.

Gum is built around gum base, the sticky building block that gives the product its trademark chewable elastic texture. This constituted nearly 20% of gum’s volume and was made almost entirely from natural latex and rubber in the 1930s. Access to these inputs were arguably the most critical of the US war effort. While sugar availability to manufacturers was initially reduced by 30%, access to latex slammed shut with the immediate Japanese occupation of rubber producing regions in Southeast Asia. More than 90% of readily available latex had been cut off overnight, and every ton of chewing gum produced meant diverting hundreds of pounds of rubber from the aircraft, trucks, wire insulation, and gas masks protecting the swelling military ranks. The shortage was so acute that scrap rubber drives became commonplace, often at the same schools distributing those ration books. Kids couldn’t chew gum because every ounce of its most basic ingredient was being used to keep their recently inducted dads alive on battlefields around the globe.

There was simply no sugar and no gum base to be had, but even if a company somehow found a way around that, the card itself still needed paper and cardboard. Those supplies dried up just as fast. Paper was rationed, with certain parts of the economy receiving greater access. Advertising and packaging, which is what baseball cards truly were at that time, was curtailed in favor of the needs of supplying military needs. Thick, high quality cardstock was redirected to the packaging of medical supplies and war materials. Even among leisure products, baseball cards were relegated to the low tier of priorities. Production of printed books, arguably a better use of paper, increased dramatically in this period.

Availability of suitable paper supplies wouldn’t be the only limitation on a truly determined card producer. The beautiful color printing that defined the 1930s Goudey and 1941 Play Ball issues was taken off the table by limitations on the printing process itself. The vibrant reds, yellows, and blues needed for lithography became functionally impossible due to reductions in civilian access to the lead and copper that were so essential to their underlying pigments. Lead, used in ammunition and batteries, was necessary to properly reproduce yellows and reds. Copper usage, necessary for blues and greens, was redirected into production of wiring, communications equipment, and most visibly brass, the material used in shell and bullet casings. Without access to these materials any cards produced would be dull, printed in some shade of gray, and slow to dry (and therefore time consuming to produce). Card production was simply unviable with these limitations.

Beyond the availability of materials, the supply chain for leisure goods collapsed amid this industrial mobilization. Factories that once produced consumer goods didn’t just sit idle or continue at reduced capacity. They shifted to fulfilling military contracts and retooled to the goods that were suddenly much more in demand. Ford Motor switched from making Super-Deluxe two-door sedans in 1941 to launching a new B-24 Liberator bomber skyward every 63 minutes.

Those massive plants required an equally massive workforce. Willow Run, the site of that massive aircraft plant, employed 42,000 skilled workers. Each of those planes (more than 18,500 for the B-24 alone) needed an air crew of up to 10 and a multiple of that to service them in the field. The US military had stood at less than 200,000 active personnel in 1939 and swelled to more than 11 million by 1945, drawing their ranks from a civilian workforce that had previously manned all manner of commercial operations. Guys who previously printed baseball cards simply had more important, or at least higher paying, tasks to perform in the mid-1940s, making the availability of raw materials a secondary concern to the ability to even hire press operators. Why produce millions of baseball cards in Philadelphia when the same hands can float a new Liberty ship every afternoon?

Transportation bottlenecks shredded any remaining shred of optimism on the part of a potential producer of baseball cards: There was no way the stretched transportation capacity of the nation’s rail and truck availability could accommodate industrial scale baseball card distribution.

Aftermath and Rebuilding

The war ended in 1945, with European guns falling silent in May and those in Asia quieting in August. By October the Chicago Cubs were seeking MLB’s permission to fit returning veteran Clyde McCullough into their World Series lineup. Collectors could expect cards to return in 1946, right?

Wrong.

The switch that was flipped in the air above Pearl Harbor couldn’t be flipped back to the “on” position – because the switch itself had been blown to pieces. Much of the world’s population centers and industrial bases were either in ruins or still tooled to the needs of producing war materiel. The 1946 season began with teams freshening up the paint on their stadiums with the ubiquitous olive drab that was suddenly being sold by the barrel as surplus goods. Transportation networks were still strained (it takes time to replace bombed out shipping fleets) and sugar remained in short supply stateside. Farmland that had been active battlefields took years to be cleared of ordinance and brought back up to full production, leaving the remaining sugar fields and other confectionary inputs to shoulder not only the needs of the domestic market but of those of much of the world as well.

Slowly the components of candy and baseball card production began to return to form, though there were two primary limitations still at play. Sugar, the first casualty of rationing, remained the last item still subject to limitations. Natural latex remained critically scarce. New trees take 6-7 years to hit their stride, leaving quite a lag between replanting efforts and the ability to resume large scale imports. This shortage, felt acutely in 1942 and possibly the greatest threat to the US’ ability to mount a sustained response, had prompted the government to build a series of 51 petrochemical plants that rivaled the Manhattan Project in development speed and costs. These plants were tasked with developing synthetic latex substitutes and continued to do so well after the war subsided. One of the upshots of this development was the realization among gum producers that synthetic latex resulted in a more consistent gum base. The taste and chewing ability of prewar gum varied with the terroir of the trees from which their latex base was harvested. Synthetic gum base lasted longer and tasted better. Gum would emerge from the war as a better product, and all that was needed to bring this to schoolyards was the return of sugar.

Finally, nearly two years after fighting subsided and gaining confidence that an inflationary demand spike could be absorbed, the OPA in July 1947 lifted the last remaining controls on sugar. Americans’ sweet tooths (teeth?) roared back to life and candy production began to quickly ramp. By 1948 the country was awash in a sea of candy. America experienced a Halloween unlike any other, with the modern incarnation of trick-or-treating taking shape on the crest of this sugar-fueled wave. Sustained marketing of the practice from major candy producers and a heavy dose of enthusiasm for Halloween in Peanuts comic strips had a notable influence on pop culture. We never looked back.

The New War

With much of the candy market up for grabs, manufacturers looked to reestablish their market share. The war fundamentally changed gum chemistry, which was the silent partner in the baseball card industry’s return. With those sugar gates finally open in mid-’47, 1948 became the year of the great experiment and the start of what became known as the Great Bubble Gum War. The manufacturers knew the demand was there, but they were still financially cautious and still contending with the last material constraints. This wasn’t just business strategy, it was psychological trauma preventing true risk taking. The industry hadn’t just been paused for 7 years, it was dead. The institutional knowledge, talent, and machinery was all gone or had been repurposed. The return of baseball cards and bubble gum was marked by risk aversion rather than quality, and it showed in industrial scale PTSD.

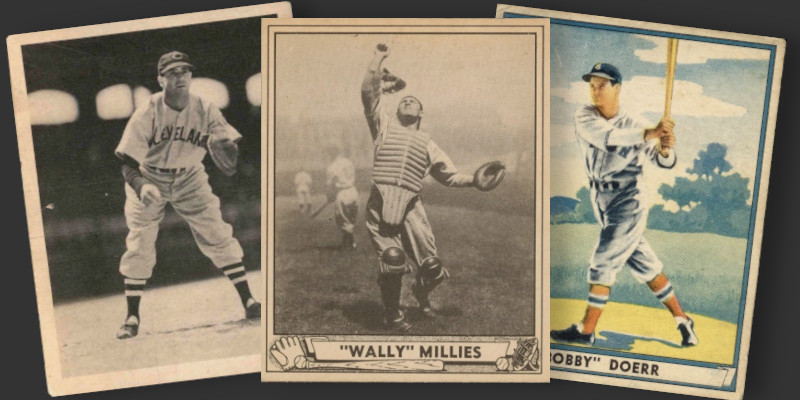

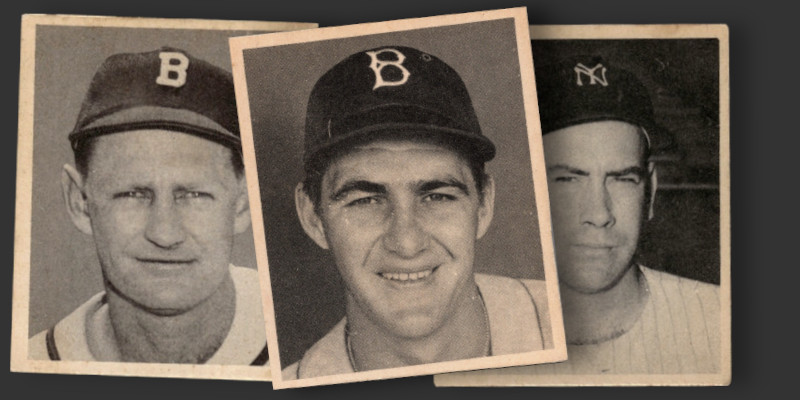

Bowman Gum, formerly known as Gum, Inc., was the first to market in 1948. They issued the first real baseball card set since 1941 and their strategy was pure caution. Confectioners had missed much of the financial upside experienced by recipients of wartime contracts and were wary of repeating the hardship that had sent National Chicle into bankruptcy and effectively put Goudey on financial life support. They put out a tiny 48 card set that was distributed with their Blony brand gum. It was a clear attempt to just test the waters without spending a lot of money and was a physical downgrade from the pre-war golden age with every cost cutting choice they could.

The ’48 Bowman set was a simple black and white affair, reintroducing cards in a style almost exactly matching the firm’s debut Play Ball issue of 1939. Player selection was limited, with just a few dozen names comprising the entire checklist and many of the game’s biggest personalities (e.g. Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Hal Newhouser) notably absent. The critical difference was size, with the new cards conveying their subjects in an area 32% smaller than the last pre-war cards. The cards were more of a reflexive flinch than a forward-leaning new product. They were driven entirely by the need to be cheap and first to market, not the best.

Despite the low quality, the sheer appetite of the market told its own story. Sales data suggests about 1.25 million of each Bowman card were sold, showing the industry that the market for baseball cards was very much alive and starved for product.

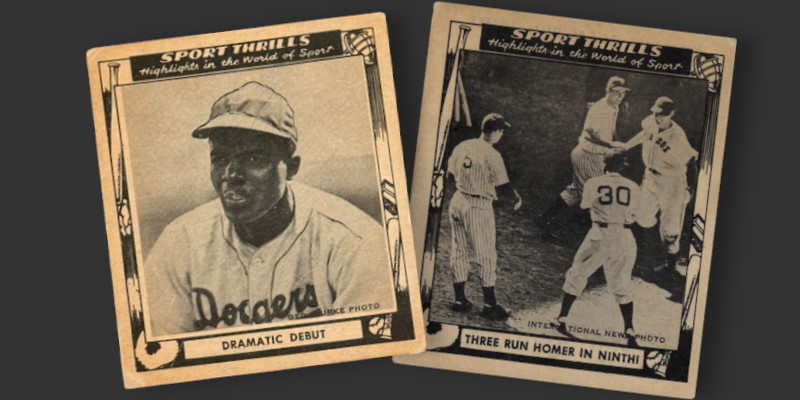

Seeing early success, the dominant (and litigious) gum producer moved quickly to protect its market. Philadelphia Gum, the upstart maker of bubble gum cigars in Bowman’s hometown of Philadelphia, marketed a 20 card baseball issue with its Swell brand penny gum under the banner “Sport Thrills.” Blocked by Bowman’s exclusive player contracts from producing traditional baseball cards, Swell produced baseball card sized “news reports” that depicted well known baseball highlights with wire service photos. Bowman didn’t produce a Jackie Robinson rookie card or put Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams on cardboard in ’48, but Swell did under “headlines” like “Dramatic Debut” and “Three Run Homer in Ninth!” Bowman still took Philadelphia Gum to court and succeeded in scaring off their competitor entirely from the immediate post-war baseball card market.

And what about Topps, the future giant of baseball cards? They produced their first baseball cards in 1948 as well, though their entry to the market was bizarre. If Bowman’s cards were small, Topps’ were microscopic. They were the size of a postage stamp and appeared blank when first removed from their wrapper. Purchasers of the cards marketed as “Magic Photos” needed to “develop” their collectibles by holding them to a strong light. Eventually, a low resolution sepia image would appear. These weren’t so much baseball cards as they were ghosts of the past. Until they were developed, the images on these cards was a ghost until the sun brought them back to life, just like the memory of cards themselves emerging after the war.

Topps (mostly) avoided the active baseball players under contract with Bowman, electing instead to focus on players like Babe Ruth and Walter Johnson that had long left the playing field. Calling this a baseball issue was a stretch, considering that only 19 of the 252 names in this wide-ranging set were baseball players.

1948 wasn’t so much a triumphant return of baseball cards so much as it was a period of purgatory. Cards were caught in this ghostly state of being unable to fully return to the emerging world of the living. Death had come from the sky for the fiscally weak world of baseball cards in December 1941, followed by a gray, confused wartime purgatory and the detection of a faint pulse in 1948.

Bowman, despite its tiny black and white cards, look like the unchallenged leader going into 1949. This was the year in which the industry dropped its caution and began aggressively competing, launching the true post-war golden age of baseball cards.

That aggressive challenge came not from Topps or Swell, but from Chicago’s Leaf Brands. They took one look at Bowman’s austerity, the small size, the lack of color and just said, “We can do better.” They roared into production, aiming their printing presses right at Bowman’s cheap product and signaling their superiority right from the outset. Leaf cards were marketed as “full size,” returning cards to the pre-war standard that had defined playground games from a decade earlier. Player names were prominently displayed in block letters, and the sheer quantity of those names (49 in the first series against Bowman’s 36) immediately hit collectors with more choice. Leaf’s supersaturated cards stood out not only by the quantity and size, but through ultra vivid colors that outshone anything previously seen. Leaf had poked its head out of the industry foxhole long enough to notice that sugar, latex, and every color pigment imaginable were once again available. The return of baseball cards was also the return of raw materials in everyday life. The gray cardboard winter was over.

It was Leaf’s surprise competitive attack that ended the tentative caution of the prior year’s cards. The new cards didn’t bear the scars of those that came before them. The trauma was nowhere to be found in the design choices. The gray and olive drab that marked so much of the recent past gave way to colors that seemed to come from another world. The bright colors more or less represented the rebuilding of a postwar America, a process that marked the effective end of the conflict after multiple years of scarcity that had followed the silencing of the guns in 1945.

Bowman and Leaf would fight it out that spring in a multi-front, running courtroom battle resulting in the establishment of the rules of engagement for putting player likenesses on cardboard. Baseball lineups bulked up in quality with the return of veteran players and spreading racial integration. Massive attendance surges set records at ballparks across the country, and the king of the old guard, Babe Ruth, passed away.

Baseball cards were back.