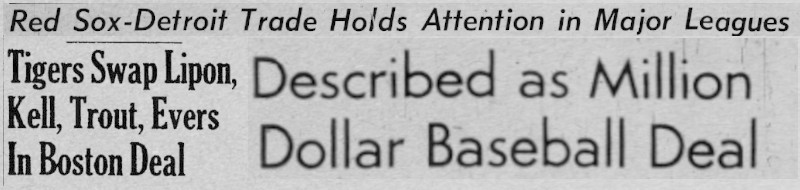

1952 was the year of the “Million Dollar Swap,” a surprise June 3 trade between the Boston Red Sox and Detroit Tigers. Nine players switched home fields after a late evening phone call between the teams’ general managers. This was the story of the 1952 season until the Yankees secured their record fifth consecutive championship.

Detroit had won 7 pennants and was only a few years removed from taking the 1945 World Series. The team entered the 1952 season with a couple of Hall of Famers on its roster and a very capable four man pitching rotation. This was a team that had a history of winning, having rarely dipped below a .500 record for long in the previous decades and never finishing last in franchise history. Detroit began the year just one season removed from having finished 3 games away from replacing the Yankees in the World Series and largely had the same roster that had put them in that position.

Imagine fans’ surprise to find that same squad in last place at the beginning of June. The Tigers started the year with an 8 game losing streak and were 13-27 by June 2. This capped off an entire month in last place in a league containing the American League punching bags Philadelphia A’s and Washington Senators. Following a three game sweep by Washington and dropping the first game of a series against the Athletics, Detroit’s newly installed general manager Charlie Gehringer called his Red Sox counterpart.

That phone call resulted in the largest trade seen until that point in baseball history. Gehringer hit the panic button and shipped off Hall of Famer George Kell, Dizzy Trout, Hoot Evers, and Johnny Lipon. Detroit received back Walt Dropo, Don Lenhardt, Johnny Pesky, Fred Hatfield, and Bill Wight. Detroit also added Johnny Hopp the next day after his late May release from the Yankees.

This was a trade worthy of newspaper headlines. Sports sections covered the story for a week following the deal, with a few localities even giving the swap front page billing. The transaction was reported to be the biggest of all time, both in terms of the quantity of players changing addresses and the quality of many of the names involved. One writer noted the cumulative salaries earned by the players being exchanged and dubbed the deal the “Million Dollar Swap.” A million bucks was quite the sum in 1952, considering the entire Pittsburgh Pirates franchise had been sold for $2.5 million just a few years earlier.

Reaction was immediate. Kell was reportedly shocked to be considered tradeable. Pesky, known as “Mr. Red Sox,” repeatedly told interviewers that he couldn’t believe it while also trying to tell listeners that he was excited about his opportunity to play with a new team. Nobody believed him either. The Boston Record polled Sox fans on who “won” the trade and came away with the Tigers coming out on top by a 9:1 margin. When asked similar questions Detroit fans generally agreed, though this may have been influenced by their dismal showing at the beginning of the season.

Descriptions of the trade generally broke it down as a 2:1 exchange of Walt Dropo and Don Lenhardt for George Kell, followed by a bit of filler. Kell was a batting champ who led the league in hits the previous two seasons. Dropo and Lenhardt were in 2nd and 3rd place in RBIs the day of the trade. Lenhardt averaged 20 home runs per full season and had won that night’s Red Sox game with a 10th inning walk off grand slam.

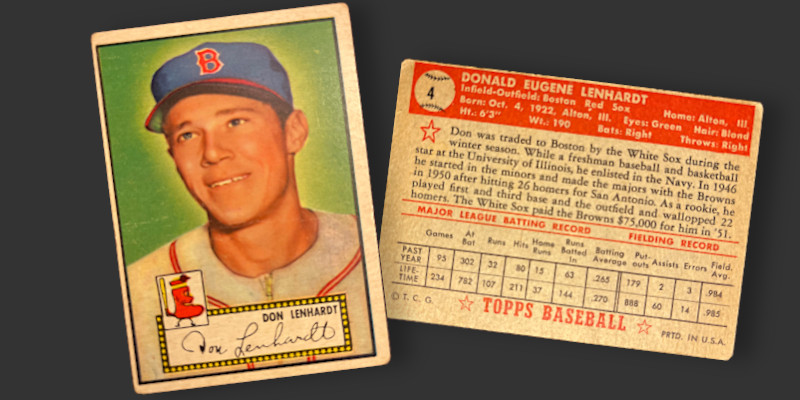

Kell was in his 10th big league season, a fact that may have induced Detroit to move a player who many believed inhabited an untouchable roster spot. Entering his 30s, sooner or later he would stop running out so many hits. Lenhardt and Dropo, on the other hand, had combined MLB experience of less than 10 years. Lenhardt had hit 44 home runs so far in his career 264 games, a rate on par with the career-to-date production of a Duke Snider or Stan Musial. Anyone inclined towards an optimistic frame of mind could start to imagine a turnaround for the Tigers. Lenhardt’s baseball cards were not just a common to Boston fans opening packs of bubble gum. By the time summer came around Detroit fans were eagerly making their own trades to get Lenhardt cardboard.

That enthusiasm didn’t last long. Although he only reached the big leagues in 1950, Lenhardt’s career had barely more than 200 games left to go at the time of the trade. Detroit traded him away to the Browns just two months later.

Excitement over everything involved in the biggest trade ever died down pretty quick. The Tigers never left the bottom of the standings and finished 45 games out of contention. Gehringer’s front office would make an even larger 12 player trade the following year and a 17 player trade between the Yankees and Orioles in 1954 erased any memory of the original deal.

One year after the 1952 Tigers/Red Sox trade, 2 of the 9 players involved had already moved on to other teams. None of the 9 were with their new team five years after the trade, and two thirds had retired from the game by the end of the 1957 season.

1952 Topps

Everyone involved in the 9-man Million Dollar Swap appears in the 1952 Topps checklist. All appear as members of their original teams, regardless of what point in the season their cards were released. Even Johnny Hopp, signed as a free agent at the time of the trade, is depicted as a New York Yankees outfielder. Fred Hatfield’s card is a late-season high number and lists him as a Detroit Tiger, though it does mention his having been traded in the biographical text on the back.

Don Lenhardt appears in his brief role as a member of the Boston Red Sox as card #4 in the ’52 Topps checklist. The design of these cards were initially laid out by hand, resulting in some elements not quite appearing symmetrical. The card number in the upper left, for example, is offset ever so slightly to the left rather than being perfectly centered. It’s lined up as if this card was going to appear with a double-digit card number rather than the singular “4” inside that colorless baseball. Other cards positioned in the 1-9 range exhibit some variance in the placement of their numbers, though none are as pronounced as this one.

The front of Lenhardt’s card likewise has a bit of variance in how his name appears. The printed text is fully aligned to the right over the facsimile signature rather than being centered as in the majority of the checklist. Topps seems to have been all over the place with this design element, never quite standardizing on any particular alignment scheme.

The biographical text details the Red Sox position player’s rapid-fire movement from the Browns to the White Sox to the Red Sox in the previous year, a journey that took him on a tour of most of the multi-team cities in baseball. The card also helpfully describes his position as “Infield-Outfield,” implying he could have just as easily been described by the phrase “non-pitcher.”